Artist Writings: Critical Essays, Reception, and Conditions of Production Since the 60S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constellation & Correspondences

LIBRARY CONSTELLATION & CORRESPONDENCES AND NETWORKING BETWEEN ARTISTS ARCHIVES 1970 –1980 KATHY ACKER (RIPOFF RED & THE BLACK TARANTULA) MAC ADAMS ART & LANGUAGE DANA ATCHLEY (THE EXHIBITION COLORADO SPACEMAN) ANNA BANANA ROBERT BARRY JOHN JACK BAYLIN ALLAN BEALY PETER BENCHLEY KATHRYN BIGELOW BILL BISSETT MEL BOCHNER PAUL-ÉMILE BORDUAS GEORGE BOWERING AA BRONSON STU BROOMER DAVID BUCHAN HANK BULL IAN BURN WILLIAM BURROUGHS JAMES LEE BYARS SARAH CHARLESWORTH VICTOR COLEMAN (VIC D'OR) MARGARET COLEMAN MICHAEL CORRIS BRUNO CORMIER JUDITH COPITHORNE COUM KATE CRAIG (LADY BRUTE) MICHAEL CRANE ROBERT CUMMING GREG CURNOE LOWELL DARLING SHARON DAVIS GRAHAM DUBÉ JEAN-MARIE DELAVALLE JAN DIBBETS IRENE DOGMATIC JOHN DOWD LORIS ESSARY ANDRÉ FARKAS GERALD FERGUSON ROBERT FILLIOU HERVÉ FISCHER MAXINE GADD WILLIAM (BILL) GAGLIONE PEGGY GALE CLAUDE GAUVREAU GENERAL IDEA DAN GRAHAM PRESTON HELLER DOUGLAS HUEBLER JOHN HEWARD DICK NO. HIGGINS MILJENKO HORVAT IMAGE BANK CAROLE ITTER RICHARDS JARDEN RAY JOHNSON MARCEL JUST PATRICK KELLY GARRY NEILL KENNEDY ROY KIYOOKA RICHARD KOSTELANETZ JOSEPH KOSUTH GARY LEE-NOVA (ART RAT) NIGEL LENDON LES LEVINE GLENN LEWIS (FLAKEY ROSE HIPS) SOL LEWITT LUCY LIPPARD STEVE 36 LOCKARD CHIP LORD MARSHALORE TIM MANCUSI DAVID MCFADDEN MARSHALL MCLUHAN ALBERT MCNAMARA A.C. MCWHORTLES ANDREW MENARD ERIC METCALFE (DR. BRUTE) MICHAEL MORRIS (MARCEL DOT & MARCEL IDEA) NANCY MOSON SCARLET MUDWYLER IAN MURRAY STUART MURRAY MAURIZIO NANNUCCI OPAL L. NATIONS ROSS NEHER AL NEIL N.E. THING CO. ALEX NEUMANN NEW YORK CORRES SPONGE DANCE SCHOOL OF VANCOUVER HONEY NOVICK (MISS HONEY) FOOTSY NUTZLE (FUTZIE) ROBIN PAGE MIMI PAIGE POEM COMPANY MEL RAMSDEN MARCIA RESNICK RESIDENTS JEAN-PAUL RIOPELLE EDWARD ROBBINS CLIVE ROBERTSON ELLISON ROBERTSON MARTHA ROSLER EVELYN ROTH DAVID RUSHTON JIMMY DE SANA WILLOUGHBY SHARP TOM SHERMAN ROBERT 460 SAINTE-CATHERINE WEST, ROOM 508, SMITHSON ROBERT STEFANOTTY FRANÇOISE SULLIVAN MAYO THOMSON FERN TIGER TESS TINKLE JASNA MONTREAL, QUEBEC H3B 1A7 TIJARDOVIC SERGE TOUSIGNANT VINCENT TRASOV (VINCENT TARASOFF & MR. -

Taking Intellectual Property Into Their Own Hands

Taking Intellectual Property into Their Own Hands Amy Adler* & Jeanne C. Fromer** When we think about people seeking relief for infringement of their intellectual property rights under copyright and trademark laws, we typically assume they will operate within an overtly legal scheme. By contrast, creators of works that lie outside the subject matter, or at least outside the heartland, of intellectual property law often remedy copying of their works by asserting extralegal norms within their own tight-knit communities. In recent years, however, there has been a growing third category of relief-seekers: those taking intellectual property into their own hands, seeking relief outside the legal system for copying of works that fall well within the heartland of copyright or trademark laws, such as visual art, music, and fashion. They exercise intellectual property self-help in a constellation of ways. Most frequently, they use shaming, principally through social media or a similar platform, to call out perceived misappropriations. Other times, they reappropriate perceived misappropriations, therein generating new creative works. This Article identifies, illustrates, and analyzes this phenomenon using a diverse array of recent examples. Aggrieved creators can use self-help of the sorts we describe to accomplish much of what they hope to derive from successful infringement litigation: collect monetary damages, stop the appropriation, insist on attribution of their work, and correct potential misattributions of a misappropriation. We evaluate the benefits and demerits of intellectual property self-help as compared with more traditional intellectual property enforcement. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38KP7TR8W Copyright © 2019 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Inc. -

Surface Work

Surface Work Private View 6 – 8pm, Wednesday 11 April 2018 11 April – 19 May 2018 Victoria Miro, Wharf Road, London N1 7RW 11 April – 16 June 2018 Victoria Miro Mayfair, 14 St George Street, London W1S 1FE Image: Adriana Varejão, Azulejão (Moon), 2018 Oil and plaster on canvas, 180 x 180cm. Photograph: Jaime Acioli © the artist, courtesy Victoria Miro, London / Venice Taking place across Victoria Miro’s London galleries, this international, cross-generational exhibition is a celebration of women artists who have shaped and transformed, and continue to influence and expand, the language and definition of abstract painting. More than 50 artists from North and South America, Europe, the Middle East and Asia are represented. The earliest work, an ink on paper work by the Russian Constructivist Liubov Popova, was completed in 1918. The most recent, by contemporary artists including Adriana Varejão, Svenja Deininger and Elizabeth Neel, have been made especially for the exhibition. A number of the artists in the exhibition were born in the final decades of the nineteenth century, while the youngest, Beirut-based Dala Nasser, was born in 1990. Work from every decade between 1918 and 2018 is featured. Surface Work takes its title from a quote by the Abstract Expressionist painter Joan Mitchell, who said: ‘Abstract is not a style. I simply want to make a surface work.’ The exhibition reflects the ways in which women have been at the heart of abstract art’s development over the past century, from those who propelled the language of abstraction forward, often with little recognition, to those who have built upon the legacy of earlier generations, using abstraction to open new paths to optical, emotional, cultural, and even political expression. -

The New Yorker April 05, 2021 Issue

PRICE $8.99 APRIL 5, 2021 APRIL 5, 2021 4 GOINGS ON ABOUT TOWN 11 THE TALK OF THE TOWN Jonathan Blitzer on Biden and the border; from war to the writers’ room; so far no sofas; still Trump country; cooking up hits. FEED HOPE. ANNALS OF ASTRONOMY Daniel Alarcón 16 The Collapse at Arecibo FEED LOVE. Puerto Rico loses its iconic telescope. SHOUTS & MURMURS Michael Ian Black 21 My Application Essay to Brown (Rejected) DEPT. OF SCIENCE Kathryn Schulz 22 Where the Wild Things Go The navigational feats of animals. PROFILES Rachel Aviv 28 Past Imperfect A psychologist’s theory of memory. COMIC STRIP Emily Flake 37 “Visions of the Post-Pandemic Future” OUR LOCAL CORRESPONDENTS Ian Frazier 40 Guns Down How to keep weapons out of the hands of kids. FICTION Sterling HolyWhiteMountain 48 “Featherweight” THE CRITICS BOOKS Jerome Groopman 55 Assessing the threat of a new pandemic. 58 Briefly Noted Madeleine Schwartz 60 The peripatetic life of Sybille Bedford. PODCAST DEPT. Hua Hsu 63 The athletes taking over the studio. THE ART WORLD Peter Schjeldahl 66 Niki de Saint Phalle’s feminist force. ON TELEVISION Doreen St. Félix 68 “Waffles + Mochi,” “City of Ghosts.” POEMS Craig Morgan Teicher 35 “Peers” Kaveh Akbar 52 “My Empire” COVER R. Kikuo Johnson “Delayed” DRAWINGS Johnny DiNapoli, Tom Chitty, P. C. Vey, Mick Stevens, Zoe Si, Tom Toro, Adam Douglas Thompson, Suerynn Lee, Roz Chast, Bruce Eric Kaplan, Victoria Roberts, Will McPhail SPOTS André da Loba CONTRIBUTORS Caring for the earth. ©2020 KENDAL Rachel Aviv (“Past Imperfect,” p. 28) is a Ian Frazier (“Guns Down,” p. -

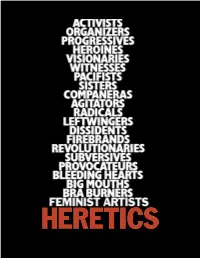

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979

Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979 Dennis, M. Submitted version deposited in Coventry University’s Institutional Repository Original citation: Dennis, M. () Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979. Unpublished MSC by Research Thesis. Coventry: Coventry University Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Some materials have been removed from this thesis due to Third Party Copyright. Pages where material has been removed are clearly marked in the electronic version. The unabridged version of the thesis can be viewed at the Lanchester Library, Coventry University. Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979 Mark Dennis A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the University’s requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy/Master of Research September 2016 Library Declaration and Deposit Agreement Title: Forename: Family Name: Mark Dennis Student ID: Faculty: Award: 4744519 Arts & Humanities PhD Thesis Title: Strategic Anomalies: Art & Language in the Art School 1969-1979 Freedom of Information: Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA) ensures access to any information held by Coventry University, including theses, unless an exception or exceptional circumstances apply. In the interest of scholarship, theses of the University are normally made freely available online in the Institutions Repository, immediately on deposit. -

Williams College/Clark Art Institute

GRADUATE PROGRAM IN THE HISTORY OF ART Williams College/Clark Art Institute Summer 2001 NEWSLETTER ~ '" ~ o b iE The Class of 2001 at their Hooding Ceremony. From left to right: Mark Haxthausen, Jeffrey T. Saletnik, Clare S. Elliott, Jennifer W. King, Jennifer T. Cabral, Karly Whitaker, Rachel Butt, Elise Barclay, Anna Lee Kamplain, and Marc Simpson LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR CHARLES W. (MARK) HAx'rHAUSEN Faison-Pierson-Stoddard Professor of Art History, Director of the Graduate Program With this issue we are extremely pleased to revive the Graduate Program's ANNuAL NEWSLETTER, in a format that is greatly expanded from its former incarnation. This publication will appear once a year, toward the end of the summer, bringing you news about the program, Williams, the Clark, our faculty, students, and graduates. The return of the newsletter is a fruit of one of the happy developments of a remarkably successful year-the creation of the position ofAsSOCIATE DIRECTOR of the Graduate Program. In recent years, with the introduction of the QualifYing Paper and Annual Symposium, the workload in the Graduate Program had seriously outgrown the capacities of its small staff. With the naming ofMARc SIMPSON to the new post, we have the resources not only to handle existing administrative demands but to expand our activities into neglected areas, one ofwhich is the publication of this newsletter, for which Marc serves as editor. We feel especially fortunate to have added Marc to the Program. A leading scholar of American art, he received his Ph.D. from Yale and served from 1985 to 1994 as Ednah Root Curator ofAmerican Paintings at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. -

Art and Language 14Th November – 18Th January 2003 52 - 54 Bell Street

Art and Language 14th November – 18th January 2003 52 - 54 Bell Street Lisson Gallery is delighted to announce an exhibition by Art & Language. Art and Language played a key role in the birth of Conceptual Art both theoretically and in terms of the work produced. The name Art & Language was first used by Michael Baldwin, David Bainbridge, Harold Hurrell and Terry Atkinson in 1968 to describe their collaborative work which had been taking place since 1966-67 and as the title of the journal dedicated to the theoretical and critical issues of conceptual art. The collaboration widened between 1969 and 1970 to include Ian Burn, Mel Ramsden, Joseph Kosuth and Charles Harrison. The collaborative nature of the venture was conceived by the artists as offering a critical inquiry into the social, philosophical and psychological position of the artist which they regarded as mystification. By the mid-1970s a large body of critical and theoretical as well as artistic works had developed in the form of publications, indexes, records, texts, performances and paintings. Since 1977, Art and Language has been identified with the collaborative work of Michael Baldwin and Mel Ramsden and with the theoretical and critical collaboration of these two with Charles Harrison. The process of indexing lies at the heart of the endeavours of Art and Language. One such project that will be included in the exhibition is Wrongs Healed in Official Hope, a remaking of an earlier index, Index 01, produced by Art & Language for the Documenta of 1972. Whereas Index 01 was intended as a functioning tool in the recovery and public understanding of Art and Language, Wrongs Healed in Official Hope is a ‘logical implosion’ of these early indexes as conversations questioning the process of indexing became the material of the indexing project itself. -

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979 Art & Language Large Print Guide

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964–1979 12 April – 29 August 2016 Art & Language Large Print Guide Please return to exhibition entrance Art & Language 1 To focus on reading rather than looking marked a huge shift for art. Language was to be used as art to question art. It would provide a scientific and critical device to address what was wrong with modernist abstract painting, and this approach became the basis for the activity of the Art & Language group, active from about 1967. They investigated how and under what conditions the naming of art takes place, and suggested that meaning in art might lie not with the material object itself, but with the theoretical argument underpinning it. By 1969 the group that constituted Art & Language started to grow. They published a magazine Art-Language and their practice became increasingly rooted in group discussions like those that took place on their art theory course at Coventry College of Art. Theorising here was not subsidiary to art or an art object but the primary activity for these artists. 2 Wall labels Clockwise from right of wall text Art & Language (Mel Ramsden born 1944) Secret Painting 1967–8 Two parts, acrylic paint on canvas and framed Photostat text Mel Ramsden first made contact with Art & Language in 1969. He and Ian Burn were then published in the second and third issues of Art-Language. The practice he had evolved, primarily with Ian Burn, in London and then after 1967 in New York was similar to the critical position regarding modernism that Terry Atkinson and Michael Baldwin were exploring. -

Chaos Theory and Robert Wilson: a Critical Analysis Of

CHAOS THEORY AND ROBERT WILSON: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF WILSON’S VISUAL ARTS AND THEATRICAL PERFORMANCES A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts Of Ohio University In partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Shahida Manzoor June 2003 © 2003 Shahida Manzoor All Rights Reserved This dissertation entitled CHAOS THEORY AND ROBERT WILSON: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF WILSON’S VISUAL ARTS AND THEATRICAL PERFORMANCES By Shahida Manzoor has been approved for for the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by Charles S. Buchanan Assistant Professor, School of Interdisciplinary Arts Raymond Tymas-Jones Dean, College of Fine Arts Manzoor, Shahida, Ph.D. June 2003. School of Interdisciplinary Arts Chaos Theory and Robert Wilson: A Critical Analysis of Wilson’s Visual Arts and Theatrical Performances (239) Director of Dissertation: Charles S. Buchanan This dissertation explores the formal elements of Robert Wilson’s art, with a focus on two in particular: time and space, through the methodology of Chaos Theory. Although this theory is widely practiced by physicists and mathematicians, it can be utilized with other disciplines, in this case visual arts and theater. By unfolding the complex layering of space and time in Wilson’s art, it is possible to see the hidden reality behind these artifacts. The study reveals that by applying this scientific method to the visual arts and theater, one can best understand the nonlinear and fragmented forms of Wilson's art. Moreover, the study demonstrates that time and space are Wilson's primary structuring tools and are bound together in a self-renewing process. -

Schor Moma Moma

12/12/2016 M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking3 H O M E A B O U T L I N K S Browse: Home / 2016 / December / 09 / M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking CONNE CT 3 Mira's Facebook Page DE CE MBE R 9 , 2 0 1 6 Subscribe in a Reader Subscribe by email M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking3 miraschor.com The first issue of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A Journal of Contemporary Art Issues, was published in December 1986. M/E/A/N/I/N/G is a collaboration between two artists, TAGS Susan Bee and Mira Schor, both painters with expanded interests in writing and 2016 election Abstract politics, and an extended community of artists, art critics, historians, theorists, and Expressionism ACTUAW poets, whom we sought to engage in discourse and to give a voice to. Activism Ana Mendieta Andrea For our 30th anniversary and final issue, we have asked some longtime contributors Geyer Andrea Mantegna Anselm and some new friends to create images and write about where they place meaning Kiefer Barack Obama CalArts craft today. As ever, we have encouraged artists and writers to feel free to speak to the Cubism DAvid Salle documentary concerns that have the most meaning to them right now. film drawing Edwin Denby Facebook feminism Every other day from December 5 until we are done, a grouping of contributions will Feminist art appear on A Year of Positive Thinking. -

Une Bibliographie Commentée En Temps Réel : L'art De La Performance

Une bibliographie commentée en temps réel : l’art de la performance au Québec et au Canada An Annotated Bibliography in Real Time : Performance Art in Quebec and Canada 2019 3e édition | 3rd Edition Barbara Clausen, Jade Boivin, Emmanuelle Choquette Éditions Artexte Dépôt légal, novembre 2019 Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec Bibliothèque et Archives du Canada. ISBN : 978-2-923045-36-8 i Résumé | Abstract 2017 I. UNE BIBLIOGraPHIE COMMENTÉE 351 Volet III 1.11– 15.12. 2017 I. AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGraPHY Lire la performance. Une exposition (1914-2019) de recherche et une série de discussions et de projections A B C D E F G H I Part III 1.11– 15.12. 2017 Reading Performance. A Research J K L M N O P Q R Exhibition and a Series of Discussions and Screenings S T U V W X Y Z Artexte, Montréal 321 Sites Web | Websites Geneviève Marcil 368 Des écrits sur la performance à la II. DOCUMENTATION 2015 | 2017 | 2019 performativité de l’écrit 369 From Writings on Performance to 2015 Writing as Performance Barbara Clausen. Emmanuelle Choquette 325 Discours en mouvement 370 Lieux et espaces de la recherche 328 Discourse in Motion 371 Research: Sites and Spaces 331 Volet I 30.4. – 20.6.2015 | Volet II 3.9 – Jade Boivin 24.10.201 372 La vidéo comme lieu Une bibliographie commentée en d’une mise en récit de soi temps réel : l’art de la performance au 374 Narrative of the Self in Video Art Québec et au Canada. Une exposition et une série de 2019 conférences Part I 30.4.