Young Tom Wharton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whartons Wharton Hall

THE WHARTONS OF WHARTON HALL BY EDWARD ROSS WHARTON, M.A. LATE FELLOW OF JESUS COLLEGE, OXFORD WITH FIORTRAIT AND ILLUSTRATIONS OXFORD PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON PUBLISHED BY HENRY FROWDE 1898 OXFORD: HORACE HART PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY THE WHARTONS OF WHARTON HALL NOTE Tars little volume is printed as a remembrance of my husband. It contains first, a reprint of the obituary from the ACADEMY, written by his friend Air. J. S. CoTTON; secondly, a bibliography of his published writings; thirdly, an article on the Wharton.r of Wharton Hall, the last thing upon which he was engaged, entbodying viii Note the result of his genealogical re searches about the Wharton family. The illustrations are from photo graphs by myself. The portrait was taken in March 1 8 9 6 ; and the two tombs of the Wharton family were done during a tour in which I accompanied him the .rummer before he died. MARIE WHARTON. MERTON LEA, OXFORD, Nov. 24, 1898. G~u,4r~ (Foss ~ij4rfo1t ~ IN MEMORIAM [F~om the 'Academ1• of June 13, 1896.J ~ THE small band of students of philology in England has suffered a heavy loss by the death of Mr. E. R. Wharton, fellow of Jesus College, Oxford. Though never very strong, he seemed latterly to have recovered from the effects of more than one severe illness. Up to Wednesday of last week he was able to be about and do his ordinary work. Alarming symptoms then suddenly set in, and he died on the afternoon of Thursday, June 4, in his house at Oxford, ?verlooking the Parks. -

Lyvennet - Our Journey

Lyvennet - Our Journey David Graham 24th September 2014 Agenda • Location • Background • Housing • Community Pub • Learning • CLT Network Lyvennet - Location The Lyvennet Valley • Villages - Crosby Ravensworth, Maulds Meaburn, Reagill and Sleagill • Population 750 • Shop – 4mls • Bank – 7 mls • A&E – 30mls • Services – • Church, • Primary School, • p/t Post Office • 1 bus / week • Pub The Start – late 2008 • Community Plan • Housing Needs Survey • Community Feedback Cumbria Rural Housing Trust Community Land Trust (CLT) The problem • 5 new houses in last 15 years • Service Centre but losing services • Stagnating • Affordability Ratio 9.8 (House price / income) Lyvennet Valley 5 Yearly Average House Price £325 Cumbria £300 £275 0 £250 0 Average 0 , £ £225 £182k £200 £175 £150 2000- 2001- 2002- 2003- 2004- 2005- 2006- 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Years LCT “Everything under one roof” Local Residents Volunteers Common interest Various backgrounds Community ‘activists’ Why – Community Land Trust • Local occupancy a first priority • No right to buy • Remain in perpetuity for the benefit of the community • All properties covered by a Local Occupancy agreement. • Reduced density of housing • Community control The community view was that direct local stewardship via a CLT with expert support from a housing association is the right option, removing all doubt that the scheme will work for local people. Our Journey End March2011 Tenders Lyvennet 25th Jan -28th Feb £660kHCAFunding Community 2011 £1mCharityBank Developments FullPlanning 25th -

Dissenters' Schools, 1660-1820

Dissenters' Schools, 1660-1820. HE contributions of nonconformity to education have seldom been recognized. Even historians of dissent T have rarely done more than mention the academies, and speak of them as though they existed chiefly to train ministers, which was but a very; small part o:f their function, almost incidental. Tbis side of the work, the tecbnical, has again been emphasized lately by Dr. Shaw in the " Cambridge History of Modern Literature," and by Miss Parker in her " Dissenting Academies in England ": it needs tberefore no further mention. A 'brief study of the wider contribution of dissent, charity schools, clay schools, boarding schools, has been laid before the members of our Society. An imperfect skeleton, naming and dating some of the schoolmasters, may be pieced together here. It makes no 'P'r·et·ence to be exhaustive; but it deliberately: excludes tutors who were entirely engaged in the work of pre paring men for the ministry, so as to illustrate the great work clone in general education. It incorporates an analysis of the. I 66 5 returns to the Bishop of Exeter, of IVIurch's history of the Presbyterian and General Baptist Churches in the West, of Nightingale's history of Lancashire Nonconformity (marked N), of Wilson's history of dissenting churches in and near London. The counties of Devon, Lancaste.r, and Middlesex therefore are well represented, and probably an analysis of any county dissenting history would reveal as good work being done in every rplace. A single date marks the closing of the school. Details about many will be found in the Transactions of the Congregational Historical Society, to which references are given. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Mobilizing the Metropolis: Politics, Plots and Propaganda in Civil War London, 1642-1644 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3gh4h08w Author Downs, Jordan Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Mobilizing the Metropolis: Politics, Plots and Propaganda in Civil War London, 1642-1644 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Jordan Swan Downs December 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Thomas Cogswell, Chairperson Dr. Jonathan Eacott Dr. Randolph Head Dr. J. Sears McGee Copyright by Jordan Swan Downs 2015 The Dissertation of Jordan Swan Downs is approved: ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I wish to express my gratitude to all of the people who have helped me to complete this dissertation. This project was made possible due to generous financial support form the History Department at UC Riverside and the College of Humanities and Social Sciences. Other financial support came from the William Andrew’s Clark Memorial Library, the Huntington Library, the Institute of Historical Research in London, and the Santa Barbara Scholarship Foundation. Original material from this dissertation was published by Cambridge University Press in volume 57 of The Historical Journal as “The Curse of Meroz and the English Civil War” (June, 2014). Many librarians have helped me to navigate archives on both sides of the Atlantic. I am especially grateful to those from London’s livery companies, the London Metropolitan Archives, the Guildhall Library, the National Archives, and the British Library, the Bodleian, the Huntington and the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library. -

Affordable Homes for Local People: the Effects and Prospects

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Liverpool Repository Affordable homes for local communities: The effects and prospects of community land trusts in England Dr Tom Moore August 2014 Acknowledgements This research study was funded by the British Academy Small Grants scheme (award number: SG121627). It was conducted during the author’s employment at the Centre for Housing Research at the University of St Andrews. He is now based at the University of Sheffield. Thanks are due to all those who participated in the research, particularly David Graham of Lyvennet Community Trust, Rosemary Heath-Coleman of Queen Camel Community Land Trust, Maria Brewster of Liverpool Biennial, and Jayne Lawless and Britt Jurgensen of Homebaked Community Land Trust. The research could not have been accomplished without the help and assistance of these individuals. I am also grateful to Kim McKee of the University of St Andrews and participants of the ESRC Seminar Series event The Big Society, Localism and the Future of Social Housing (held in St Andrews on 13-14th March 2014) for comments on previous drafts and presentations of this work. All views expressed in this report are solely those of the author. For further information about the project and future publications that emerge from it, please contact: Dr Tom Moore Interdisciplinary Centre of the Social Sciences University of Sheffield 219 Portobello Sheffield S1 4DP Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0114 222 8386 Twitter: @Tom_Moore85 Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. i 1. Introduction to CLTs ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 The policy context: localism and community-led housing ........................................................... -

Bibliography

JOHN HAMPDEN Bibliography Primary Sources: Letters from John Hampden to Sir John Hotham (NRA 5408 Hotham and the University of Hull Library, Hotham MSS) Exchequer Papers for Hampden’s Greencoat Regiment, (SP28/129, National Archives) Letters from John Hampden to the Sheriff of Buckinghamshire (British Museum; Stowe MSS. 188) Letters from John Hampden to the Earl of Essex (Bodelian Library; Tanner MSS.lxii 115 and lxiii 153) Letters from John Hampden to the Buckinghamshire Deputy Lieutenants (British Museum, Facsimiles 15,858) Letter from John Hampden to Sir Thomas Barrington Letter from John Hampden to Arthur Goodwin (Bodelian Library; Carte MSS.ciii Letter from Gervaise Sleigh to his Uncle on the Battle of Brentford (Bodelian Library, MS.Don c.184.f.29) Report from the Committee for Public Safety to the Deputy Lieutenants if Hertfordshire on the Battles of Brentford and Turnham Green (HMC Portland MS.) Parliamentarian News Pamphlet entitled ‘Elegies on the Death of That worthy and accomplsh’t Gentleman Colonell John Hampden’ published October 16 th 1643 (Thomas Tracts E339, British Library) Parliamentarian News Pamphlet entitled ‘Two letters from the Earl of Essex’ published June 23 rd 1643 (Thomason Tracts E55, British Library) Parliamentarian News Pamphlet entitled ‘A true relation of a Gret fight’ (Thomason Tracts, British Library) Royalist News Pamphlet entitled ‘Prince Ruperts beating up the Rebel Quarters’ (Oxon. Wood 376, Bodleian Library) Secondary Material: *Adair, John. A life of John Hampden the Patriot 1594-164 ( Macdonald & Jane's - 1976. Thorogood - 2003. ISBN 0354040146) Adamson, Dr John. The Noble Revolt: the Overthrow of Charles I (London, 2007) Aylmer, G E. -

Briefing Paper the Big Society: News from the Frontline in Eden August

AWICS Independence…..Integrity.….Value Adrian Waite (In dependent Consultancy Services) Limited Briefing Paper The Big Society: News from the Frontline in Eden August 2010 Introduction The government’s ‘Big Society’ project was launched by David Cameron in Liverpool on 19th July 2010. As part of this, four areas have been identified as Vanguard Communities where it is intended to ‘turn government completely on its head’. These areas are Eden, Liverpool, Sutton and Windsor & Maidenhead. David Cameron said: “My great passion is building the Big Society. Anyone who’s had even a passing interest in what I’ve been saying for years will know that. “The ‘Big Society’ is…something different and bold… It’s about saying if we want real change for the long-term, we need people to come together and work together – because we’re all in this together. “(We want) Neighbourhoods who are in charge of their own destiny, who feel if they club together and get involved they can shape the world around them. “If you’ve got an idea to make life better, if you want to improve your local area, don’t just think about it – tell us what you want to do and we will try and give you the tools to make this happen.” David Cameron outlined what are to be the three major strands of Big Society which include: “First, social action. The success of the Big Society will depend on the daily decisions of millions of people – on them giving their time, effort, even money, to causes around them. So government cannot remain neutral on that – it must foster and support a new culture of voluntarism, philanthropy, social action. -

©2011 Steven M. Kawczak All Rights Reserved

©2011 STEVEN M. KAWCZAK ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BELIEFS AND APPROACHES TO DEATH AND DYING IN LATE SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND A Dissertation Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Steven M. Kawczak December, 2011 BELIEFS AND APPROACHES TO DEATH AND DYING IN LATE SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND Steven M. Kawczak Dissertation Approved: Accepted: ____________________________ ____________________________ Advisor Department Chair Michael F. Graham, Ph.D. Michael Sheng, Ph.D. ____________________________ ____________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the College Michael Levin, Ph.D. Chand K. Midha, Ph.D. ____________________________ ____________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Constance Bouchard, Ph.D. George R. Newkome, Ph.D. ____________________________ ____________________________ Faculty Reader Date Howard Ducharme, Ph.D. ____________________________ Faculty Reader Matthew Crawford, Ph.D. ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is about death and its relationship to religion in late seventeenth- century England. The primary argument is that while beliefs about death stemmed from the Reformation tradition, divergent religious reforms of Puritanism and Arminianism did not lead to differing approaches to death. People adapted religious ideas on general terms of Protestant Christianity and not specifically aligned with varying reform movements. This study links apologetics and sermons concerning spiritual death, physical death, and remedies for each to cultural practice through the lens of wills and graves to gauge religious influence. Readers are reminded of the origins of reformed thought, which is what seventeenth-century English theologians built their ideas upon. Religious debates of the day centered on the Puritan and Arminian divide, which contained significantly different ideas of soteriology, a key aspect of a good death in the English ars moriendi. -

The Wives of Henry the Eighth and the Parts They Played in History;

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNDERGRADUATE LIBRARY _„ IE .' / PRINTED IN U.S.A. Cornell University Library DA 333.A2H92 1905a The wives of Henry the Eighth and the pa 3 1924 014 590 115 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tlie Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924014590115 THE WIVES OF HENRY THE EIGHTH HENRY Fill. From a portrait fy JoST Van Cleef in the Royal Collection at Hampton Court Palace The Wives OF Henry the Eighth AND THE PARTS THEY PLAYED IN HISTORY BY MARTIN HUME AUTHOR OF "the COURTSHIPS OF QUEEN ELIZABETH ' " " THE LOVE AFFAIRS OF MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS " Thete are stars indeed. And sometimes falling enes.'" — Shakespeare URIS NEW YORK BRENTANO'S PUBLISHERS , 1 " lift Co ^ PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN PREFACE Either by chance or by the peculiar working of our constitution, the Queen Consorts of England have as a rule been nationally important only in proportion to the influence exerted by the pohtical tendencies which prompted their respective marri- ages. England has had no Catharine or Marie de Medici, no Elizabeth Farnese, no Catharine of Russia, no Caroline of Naples, no Maria Luisa of Spain, who, either through the minority of their sons or the weakness of their husbands, dominated the countries of their adoption ; the Consorts of English Kings having been, in the great majority of cases, simply domestic helpmates of their husbands and children, with comparatively small pohtical power or ambi- tion for themselves. -

Anecdotes of Painting in England : with Some Account of the Principal

C ' 1 2. J? Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/paintingineng02walp ^-©HINTESS <0>F AEHJKTID 'oat/ /y ' L o :j : ANECDOTES OF PAINTING IN ENGLAND; WITH SOME ACCOUNT OF THE PRINCIPAL ARTISTS; AND INCIDENTAL NOTES ON OTHER ARTS; COLLECTED BY THE LATE MR. GEORGE VERTUE; DIGESTED AND PUBLISHED FROM HIS ORIGINAL MSS. BY THE HONOURABLE HORACE WALPOLE; WITH CONSIDERABLE ADDITIONS BY THE REV. JAMES DALLAWAY. LONDON PRINTED AT THE SHAKSPEARE PRESS, BY W. NICOL, FOR JOHN MAJOR, FLEET-STREET. MDCCCXXVI. LIST OF PLATES TO VOL. II. The Countess of Arundel, from the Original Painting at Worksop Manor, facing the title page. Paul Vansomer, . to face page 5 Cornelius Jansen, . .9 Daniel Mytens, . .15 Peter Oliver, . 25 The Earl of Arundel, . .144 Sir Peter Paul Rubens, . 161 Abraham Diepenbeck, . 1S7 Sir Anthony Vandyck, . 188 Cornelius Polenburg, . 238 John Torrentius, . .241 George Jameson, his Wife and Son, . 243 William Dobson, . 251 Gerard Honthorst, . 258 Nicholas Laniere, . 270 John Petitot, . 301 Inigo Jones, .... 330 ENGRAVINGS ON WOOD. Arms of Rubens, Vandyck & Jones to follow the title. Henry Gyles and John Rowell, . 39 Nicholas Stone, Senior and Junior, . 55 Henry Stone, .... 65 View of Wollaton, Nottinghamshire, . 91 Abraham Vanderdort, . 101 Sir B. Gerbier, . .114 George Geldorp, . 233 Henry Steenwyck, . 240 John Van Belcamp, . 265 Horatio Gentileschi, . 267 Francis Wouters, . 273 ENGRAVINGS ON WOOD continued. Adrian Hanneman, . 279 Sir Toby Matthews, . , .286 Francis Cleyn, . 291 Edward Pierce, Father and Son, . 314 Hubert Le Soeur, . 316 View of Whitehall, . .361 General Lambert, R. Walker and E. Mascall, 368 CONTENTS OF THE SECOND VOLUME. -

A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L)

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2009-05-01 A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L) Gary P. Gillum [email protected] Susan Wheelwright O'Connor Alexa Hysi Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Gillum, Gary P.; O'Connor, Susan Wheelwright; and Hysi, Alexa, "A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L)" (2009). Faculty Publications. 12. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/12 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 833 FAIRFAX, JOHN, 1623-1700. Rare 922.542 St62f 1681 Presbýteros diples times axios, or, The true dignity of St. Paul's elder, exemplified in the life of that reverend, holy, zealous, and faithful servant, and minister of Jesus Christ Mr. Owne Stockton ... : with a collection of his observations, experiences and evidences recorded by his own hand : to which is added his funeral sermon / by John Fairfax. London : Printed by H.H. for Tho. Parkhurst at the Sign of the Bible and Three Crowns, at the lower end of Cheapside, 1681. Description: [12], 196, [20] p. ; 15 cm. References: Wing F 129. Subjects: Stockton, Owen, 1630-1680. Notes: Title enclosed within double line rule border. "Mors Triumphata; or The Saints Victory over Death; Opened in a Funeral Sermon ... " has special title page. 834 FAIRFAX, THOMAS FAIRFAX, Baron, 1612-1671. -

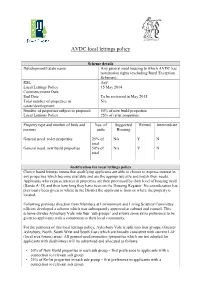

AVDC Sub Groups Local Lettings Policy

AVDC local lettings policy Scheme details Development/Estate name Any general need housing to which AVDC has nomination rights (excluding Rural Exception Schemes). RSL Any Local Lettings Policy – 15 May 2014 Commencement Date End Date To be reviewed in May 2015 Total number of properties in N/a estate/development Number of properties subject to proposed 50% of new build properties Local Lettings Policy 25% of re let properties Property type and number of beds and Nos. of Supported Rented Intermediate persons units Housing General need, re-let properties 25% of N/a Y N total General need, new build properties 50% of N/a Y N total Justification for local lettings policy Choice based lettings means that qualifying applicants are able to choose to express interest in any properties which become available and are the appropriate size and match their needs. Applicants who express interest in properties are then prioritised by their level of housing need (Bands A- D) and then how long they have been on the Housing Register. No consideration has previously been given to where in the District the applicant is from or where the property is located. Following previous direction from Members at Environment and Living Scrutiny Committee officers developed a scheme which was subsequently approved at cabinet and council. This scheme divides Aylesbury Vale into four ‘sub groups’ and allows some extra preference to be given to applicants with a connection to their local community. For the purposes of this local lettings policy, Aylesbury Vale is split into four groups, (Greater Aylesbury, North, South West and South East) which are broadly consistent with current LAF (local area forum) areas.