LMU Law Review Volume 4 Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cleveland Cavaliers (19-33) Vs

CLEVELAND CAVALIERS (19-33) VS. NEW ORLEANS PELICANS (23-29) SAT., APRIL 10, 2021 ROCKET MORTGAGE FIELDHOUSE – CLEVELAND, OH 7:30 PM ET TV: BALLY SPORTS OHIO RADIO: WTAM 1100 AM/POWER 89.1 FM WNZN 2020-21 CLEVELAND CAVALIERS GAME NOTES FOLLOW @CAVSNOTES ON TWITTER OVERALL GAME # 53 HOME GAME # 26 LAST GAME STARTERS 2020-21 REG. SEASON SCHEDULE PLAYER / 2020-21 REGULAR SEASON AVERAGES DATE OPPONENT SCORE RECORD #0 Kevin Love C • 6-8 • 247 • UCLA/USA • 13th Season 12/23 vs. Hornets 121-114 W 1-0 GP/GS PPG RPG APG SPG BPG MPG 12/26 @ Pistons 128-119** W 2-0 9/9 10.1 5.4 1.9 0.7 0.1 19.1 12/27 vs. 76ers 118-94 W 3-0 #32 Dean Wade F • 6-9 • 219 • Kansas State/USA • 2nd Season 12/29 vs. Knicks 86-95 L 3-1 GP/GS PPG RPG APG SPG BPG MPG 3-2 44/11 5.1 3.0 1.1 0.4 0.4 16.6 12/31 @ Pacers 99-119 L 1/2 @ Hawks 96-91 W 4-2 #35 Isaac Okoro F • 6-6 • 225 • Auburn/USA • Rookie 4-3 GP/GS PPG RPG APG SPG BPG MPG 1/4 @ Magic 83-103 L 47/47 8.1 2.8 1.7 1.0 0.4 31.9 1/6 @ Magic 94-105 L 4-4 #2 Collin Sexton G • 6-1 • 192 • Alabama/USA • 3rd Season 1/7 @ Grizzlies 94-90 W 5-4 GP/GS PPG RPG APG SPG BPG MPG 1/9 @ Bucks 90-100 L 5-5 45/45 24.1 2.8 4.2 1.2 0.1 35.8 1/11 vs. -

Suppuration of Powers: Abscam, Entrapment and the Politics of Expulsion Henry Biggs

Legislation and Policy Brief Volume 6 | Issue 2 Article 2 2014 Suppuration of Powers: Abscam, Entrapment and the Politics of Expulsion Henry Biggs Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/lpb Part of the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Biggs, Henry. "Suppuration of Powers: Abscam, Entrapment and the Politics of Expulsion." Legislation and Policy Brief 6, no. 2 (2014): 249-269. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Legislation and Policy Brief by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vol. 6.2 Legislation & Policy Brief 249 SUPPURATION OF POWERS: ABSCAM, ENTRAPMENT AND THE POLITICS OF EXPULSION Henry Biggs1 In a government of laws, existence of the government will be imperiled if it fails to observe the law scrupulously . to declare that the Government may commit crimes in order to secure the conviction of a private criminal – would bring terrible retribution. Against that pernicious doctrine this Court should resolutely set its face.2 Introduction .............................................................................................249 I. Abscam .................................................................................................251 A. Origins ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������251 -

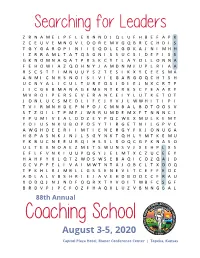

Searching for Leaders

Searching for Leaders Z R N A M E L P F L E X N N D J Q L U F H B E F A P K Z C E U V E M N G V L O O R E M V G Q B R C C H D I S T G Y G A R O P I N I I E Q D L C G D K A J N I M H H I Z R R A M L T A T Q S G N I S S U C S I D E F I S S G K N O M N A Q A T P R S K C Y T L A Y O L L O N N A F E H O W I A Z Q O H N Y J A M D N M J U P L R I A A R S C S T T I M N U U Y S Z T E S I K X Y C E E S M A A N M I C N H S N O I S I V I E G A R G O Q C H T S H U C N Y A L I C U L T U R E O S I D I E J N X C R T P J I C G E B M A N A G E M E N T K R E S C Y E A A R Y M V R O I P E R S E V E R A N C E I Y L U T K E T O T J O N L U C S M E D L I F E J Y V J L W W H I T I P I T V I R M N H D E P N P O J C M N B A L B O T O O S V S T Z O I L T P M F J W R R U M D E M X F T N N N C I Y P U M I V E A L D D Z E Y P Q C W E X M U L K E M T Y O I U S N X U B O P O S Y T I R G E T N I L G P V C A W G H D E E R I I M T I E N E R G Y F X J O N U G A H G P A S N K J N J L S G Y N K T Q H L Y M T K E M U Y K B U C N E E U R Q I H S S L X O Q C G Y K N A S O U L T E K N O A E Z M E T S W U N S V J X E H P L X S E F L F V N K I U U P Q G Y J E L M T X C Z U C E E Y H A H F Y X L Q T Z W O S W S E B A Q I C O Z Q A J D G C V P P E L I V A I M W T N T A J O B C L T X D O Q T P K H L R J M B L L G S S E N E V I T C E F F E O C A D L A L V B S H R I E J A V E H D B D O C C F R A U X O D Q J N J N D F O Q R X T Y V O I T W B F C S G F B R D V P J P C F O Z F H A Q K L U Z V B N N G B A L 88th Annual Coaching School August 3-5, 2020 Capitol Plaza Hotel, Maner Conference Center | Topeka, Kansas Keynote Speaker: Joe Coles Joe Coles is a speaker, consultant and teacher. -

Communications

MARCH 23, 2019 | NCAA TOURNAMENT - SECOND ROUND | GAME NOTES KANSAS COMMUNICATIONS # # # # 26-9 12-6 17 / 17 27-9 11-7 14 / 18 TIGERS OVERALL BIG 12 RANKING (AP/COACHES) OVERALL SEC RANKING (AP/COACHES) -VS- Bill Self 473-105 (.818) Bruce Pearl 97-71 (.577) JAYHAWKS HEAD COACH RECORD AT KU, 16TH SEASON HEAD COACH RECORD AT AU, FIFTH SEASON SCHEDULE (H: 17-0; A: 3-8; N: 6-1) GAME (4) KANSAS VS (5) AUBURN KU IN THE NCAA TOURNEY (More on pg. 49) KU OPP NCAA Championship • Second Round OVERALL (under Bill Self) 108-46 (38-14) Rnk Rnk Opponent TV Time/Result Salt Lake City, Utah • Vivint Smart Home Arena (18,284) as No. 4 seed 8-4 NOVEMBER (5-0) 36 In Round of 32 (Since 1981) 23-10 6 1/1 10/10 vs. Michigan State! ESPN W, 92-87 Saturday, March 23, 2019 • 8:40 p.m. (CT) 12 2/1 -/- VERMONT~ ESPN2 W, 84-68 16 2/1 -/- LOUISIANA JTV/ESPN+ W, 89-76 TBS JAYHAWK RADIO 21 2/2 rv/rv vs. Marquette# ESPN2 W, 77-68 NETWORK Play-by-Play: Andrew Catalon Radio: IMG Jayhawk Radio Network 23 2/2 5/5 vs. Tennessee# ESPN2 W, 87-82 ot Analysts: Steve Lappas Webcast: KUAthletics.com/Radio DECEMBER (6-1) Reporter: Lisa Byington Play-by-Play: Brian Hanni POINTS 1 2/2 -/- STANFORD ESPN W, 90-84 ot Producer: Johnathan Segal Analyst: Greg Gurley 75.7 PER GAME ›› 79.5 4 2/2 -/- WOFFORD JTV/ESPN+ W, 72-47 Director: Andy Goldberg Producer/Engineer: Steve Kincaid 8 2/2 -/- NEW MEXICO STATE^ ESPN2 W, 63-60 TIP-OFF 46.5 ‹‹ FG% 44.8 15 1/1 17/16 VILLANOVA ESPN W, 74-71 • Kansas is making its 48th NCAA Tournament appearance and has a 18 1/1 -/- SOUTH DAKOTA JTV/ESPN+ W, 89-53 108-46 record in the event. -

Vol. 5 No. 3, October 31, 1968

THE VOL. 5 NO. 3 MARIST COLLEGE, POUGHKEEPSIE, NEW YORK 12601 OCTOBER 31,1968 AUTHOR-HISTORIANS REVIEW CORE CURRICULUM FDR CAMPAIGNS EXAMINED Last Friday in the rotund hall As the conference progressed of Donnelly Hall the sixty odd both proponents and opponents Huthmacher membered faculty of Marist of the curriculum proposals College held a two hour engaged in complex.oratory and colloquim concerning heavy sanctimonializing with & Freidel curriculum revision. The light witticisms thrown in to cut conference attempted to give a down the personal monologues. clear-cut policy on changing the The chairman of the APC, Bro. Are Speakers nature of core requirements and Brian Desilets, ran the colliquim presenting a more meaningful designing the question and answer period to relate only to The Fourth Annual Franklin approach in higher education. The main- thrust in curriculum those issues pertinent to the D. Roosevelt Symposium, matter at hand. sponsored by the Marist College revision assaulted the traditional History Department in make-up of core obligations. The The structure of both cooperation with the Roosevelt Academic Policy Committee proposals as outlined in the Library and the American (APC) set forth four general committees report appeared Historical Association's Service principles to act as guidelines in questionable to neutrals, but to Center for Teachers of History, implementing needed change. conservative elements almost' took place Saturday, in the They wished the majority of frightening in its radicalism from Campus Center The theme for core requirements to be the present curriculum structure. this year's symposium was completed in Freshman year on However, a perceptive look into "F.D.R. -

Cases of the Century

Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review Volume 33 Number 2 Symposium on Trials of the Century Article 4 1-1-2000 Cases of the Century Laurie L. Levenson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Laurie L. Levenson, Cases of the Century, 33 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 585 (2000). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr/vol33/iss2/4 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CASES OF THE CENTURY Laurie L. Levenson* I. INTRODUCTION I confess. I am a "trials of the century" junkie. Since my col- lege years, I have been interested in how high-profile cases reflect and alter our society. My first experience with a so-called trial of the century was in 1976. My roommate and I took a break from our pre- med studies so that we could venture up to San Francisco, sleep in the gutters and on the sidewalks of the Tenderloin, all for the oppor- tunity to watch the prosecution of newspaper heiress, Patty Hearst. It was fascinating. The social issues of our time converged in a fed- eral courtroom While lawyers may have been fixated on the techni- cal legal issues of the trial, the public's focus was on something en- tirely different. -

Brazil-United States

Brazil-United States Judicial Dialogue Created in June 2006 as part of the Wilson Center’s Latin American Program, the BRAZIL INSTITUTE strives to foster informed dialogue on key issues important to Brazilians and to the Brazilian-U.S. relationship. We work to promote detailed analysis of Brazil’s public policy and advance Washington’s understanding of contemporary Brazilian developments, mindful of the long history that binds the two most populous democracies in the Americas. The Institute honors this history and attempts to further bilateral coop- eration by promoting informed dialogue between these two diverse and vibrant multiracial societies. Our activities include: convening policy forums to stimulate nonpartisan reflection and debate on critical issues related to Brazil; promoting, sponsoring, and disseminating research; par- ticipating in the broader effort to inform Americans about Brazil through lectures and interviews given by its director; appointing leading Brazilian and Brazilianist academics, journalists, and policy makers as Wilson Center Public Policy Scholars; and maintaining a comprehensive website devoted to news, analysis, research, and reference materials on Brazil. Paulo Sotero, Director Michael Darden, Program Assistant Anna Carolina Cardenas, Program Assistant Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org/brazil ISBN: 978-1-938027-38-3 Brazil-United States Judicial Dialogue May 11 – 13, 2011 Brazil-United States Judicial Dialogue Foreword ffirming the Rule of Law in a historically unequal and unjust Asociety has been a central challenge in Brazil since the reinstate- ment of democracy in the mid-1980s. The evolving structure, role and effectiveness of the country’s judicial system have been major factors in that effort. -

History of the U.S. Attorneys

Bicentennial Celebration of the United States Attorneys 1789 - 1989 "The United States Attorney is the representative not of an ordinary party to a controversy, but of a sovereignty whose obligation to govern impartially is as compelling as its obligation to govern at all; and whose interest, therefore, in a criminal prosecution is not that it shall win a case, but that justice shall be done. As such, he is in a peculiar and very definite sense the servant of the law, the twofold aim of which is that guilt shall not escape or innocence suffer. He may prosecute with earnestness and vigor– indeed, he should do so. But, while he may strike hard blows, he is not at liberty to strike foul ones. It is as much his duty to refrain from improper methods calculated to produce a wrongful conviction as it is to use every legitimate means to bring about a just one." QUOTED FROM STATEMENT OF MR. JUSTICE SUTHERLAND, BERGER V. UNITED STATES, 295 U. S. 88 (1935) Note: The information in this document was compiled from historical records maintained by the Offices of the United States Attorneys and by the Department of Justice. Every effort has been made to prepare accurate information. In some instances, this document mentions officials without the “United States Attorney” title, who nevertheless served under federal appointment to enforce the laws of the United States in federal territories prior to statehood and the creation of a federal judicial district. INTRODUCTION In this, the Bicentennial Year of the United States Constitution, the people of America find cause to celebrate the principles formulated at the inception of the nation Alexis de Tocqueville called, “The Great Experiment.” The experiment has worked, and the survival of the Constitution is proof of that. -

Reforming Criminal Justice Vol. 2

Reforming Criminal Justice Volume 2: Policing Erik Luna Editor and Project Director Reforming Criminal Justice Volume 2: Policing Erik Luna Editor and Project Director a report by The Academy for Justice with the support of Copyright © 2017 All Rights Reserved This report and its contents may be used for non-profit educational and training purposes and for legal reform (legislative, judicial, and executive) without written permission but with a citation to the report. The Academy for Justice www.academyforjustice.org Erik Luna, Project Director A project of the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law Arizona State University Mail Code 9520 111 E. Taylor St. Phoenix, AZ 85004-4467 (480) 965-6181 https://law.asu.edu/ Suggested Citation Bluebook: 2 REFORMING CRIMINAL JUSTICE: POLICING (Erik Luna ed., 2017). APA: Luna, E. (Ed.). (2017). Reforming Criminal Justice: Policing (Vol. 2). Phoenix, AZ: Arizona State University. CMS: Luna, Erik, ed. Reforming Criminal Justice. Vol. 2, Policing. Phoenix: Arizona State University, 2017. Printed in the United States of America Summary of Report Contents Volume 1: Introduction and Criminalization Preface—Erik Luna Criminal Justice Reform: An Introduction—Clint Bolick The Changing Politics of Crime and the Future of Mass Incarceration— David Cole Overcriminalization—Douglas Husak Overfederalization—Stephen F. Smith Misdemeanors—Alexandra Natapoff Drug Prohibition and Violence—Jeffrey A. Miron Marijuana Legalization—Alex Kreit Sexual Offenses—Robert Weisberg Firearms and Violence—Franklin E. Zimring Gangs—Scott H. Decker Criminalizing Immigration—Jennifer M. Chacón Extraterritorial Jurisdiction—Julie Rose O’Sullivan Mental Disorder and Criminal Justice—Stephen J. Morse Juvenile Justice—Barry C. Feld Volume 2: Policing Democratic Accountability and Policing—Maria Ponomarenko and Barry Friedman Legal Remedies for Police Misconduct—Rachel A. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Cleveland Cavaliers

CLEVELAND CAVALIERS (22-50) END OF SEASON GAME NOTES MAY 17, 2021 ROCKET MORTGAGE FIELDHOUSE – CLEVELAND, OH 2020-21 CLEVELAND CAVALIERS GAME NOTES FOLLOW @CAVSNOTES ON TWITTER LAST GAME STARTERS 2020-21 REG. SEASON SCHEDULE PLAYER / 2020-21 REGULAR SEASON AVERAGES DATE OPPONENT SCORE RECORD #31 Jarrett Allen C • 6-11 • 248 • Texas/USA • 4th Season 12/23 vs. Hornets 121-114 W 1-0 GP/GS PPG RPG APG SPG BPG MPG 12/26 @ Pistons 128-119** W 2-0 63/45 12.8 10.0 1.7 0.5 1.4 29.6 12/27 vs. 76ers 118-94 W 3-0 #32 Dean Wade F • 6-9 • 219 • Kansas State • 2nd Season 12/29 vs. Knicks 86-95 L 3-1 GP/GS PPG RPG APG SPG BPG MPG 3-2 63/19 6.0 3.4 1.2 0.6 0.3 19.2 12/31 @ Pacers 99-119 L 1/2 @ Hawks 96-91 W 4-2 #16 Cedi Osman F • 6-7 • 230 • Anadolu Efes (Turkey) • 4th Season 4-3 GP/GS PPG RPG APG SPG BPG MPG 1/4 @ Magic 83-103 L 59/26 10.4 3.4 2.9 0.9 0.2 25.6 1/6 @ Magic 94-105 L 4-4 #35 Isaac Okoro G • 6-6 • 225 • Auburn • Rookie 1/7 @ Grizzlies 94-90 W 5-4 GP/GS PPG RPG APG SPG BPG MPG 1/9 @ Bucks 90-100 L 5-5 67/67 9.6 3.1 1.9 0.9 0.4 32.4 1/11 vs. -

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Washington, D.C. 20535 August 24, 2020 MR. JOHN GREENEWALD JR. SUITE

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Washington, D.C. 20535 August 24, 2020 MR. JOHN GREENEWALD JR. SUITE 1203 27305 WEST LIVE OAK ROAD CASTAIC, CA 91384-4520 FOIPA Request No.: 1374338-000 Subject: List of FBI Pre-Processed Files/Database Dear Mr. Greenewald: This is in response to your Freedom of Information/Privacy Acts (FOIPA) request. The FBI has completed its search for records responsive to your request. Please see the paragraphs below for relevant information specific to your request as well as the enclosed FBI FOIPA Addendum for standard responses applicable to all requests. Material consisting of 192 pages has been reviewed pursuant to Title 5, U.S. Code § 552/552a, and this material is being released to you in its entirety with no excisions of information. Please refer to the enclosed FBI FOIPA Addendum for additional standard responses applicable to your request. “Part 1” of the Addendum includes standard responses that apply to all requests. “Part 2” includes additional standard responses that apply to all requests for records about yourself or any third party individuals. “Part 3” includes general information about FBI records that you may find useful. Also enclosed is our Explanation of Exemptions. For questions regarding our determinations, visit the www.fbi.gov/foia website under “Contact Us.” The FOIPA Request number listed above has been assigned to your request. Please use this number in all correspondence concerning your request. If you are not satisfied with the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s determination in response to this request, you may administratively appeal by writing to the Director, Office of Information Policy (OIP), United States Department of Justice, 441 G Street, NW, 6th Floor, Washington, D.C.