Soil Reconnaissance of the Panama Canal Zone and Contiguous Territory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Study Title

PANAMA – THE MANAGEMENT OF THE PANAMA CANAL WATERSHED (PCW), CASE #5 This case study is about the Panama Canal Watershed, its development in legal, technical and social terms, the problems encountered, and how an Integrated Water Resources Management approach could help it to be managed in a more sustainable way. ABSTRACT Description The Panama Canal Watershed (PCW) was developed when the Panama Canal was constructed (1904-1914). The PCW unites the basins of the Chagres and Grande Rivers into a single hydraulic system. The Chagres and Grande Rivers drain into the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans, respectively. Damming the Chagres River provides water to operate the canal locks. By the mid 1930’s, an additional lake had been created in the upper basin of the Chagres River to increase the water storage capacity of the system. In 1999, the formal limits of the PCW were established by law and segments of the Indio, Caño Sucio and Coclé del Norte River Basins were added. All these rivers drain separately into the Atlantic Ocean to the north-west of the PCW. Under the Panama Canal Treaty (1977) the Republic of Panama was obliged to provide sufficient water for the operation of the Canal and for cities in the area. This led to the creation of several national parks, the promotion of sustainable development activities, and the implementation of base-line studies, all with support from USAID (United States Agency for International Development). A Panama Canal Authority (PCA) was created by Constitutional reform in 1994 which granted legal obligations and rights to manage the PCW. -

Notes on Some Panama Canal Zone Birds with Special Reference to Their Food

304 HxL.NxN,Notes on Panama Birds. [April[Auk NOTES ON SOME PANAMA CANAL ZONE BIRDS WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THEIR FOOD. BY THOMAS HALLINAN. OBSERVATIONSwere made on the occurrence and the food, nestingand generalhabits of 440 collectedspecimens, including 159 species. The specimenshave beendeposited in the AmericanMuseum of Natural History, in New York City, and the identificationswere made by Mr. W. deW. Miller who has remarkableability as a taxonomist. The scientificpermit to collectthese birds was issuedby Gover- nor GeorgeW. Goethals. His administration, by enforcingthe existinglaws, on the Panama Canal Zone, providedprotection to the birdsand it hasmade this territory as desirableto the avifauna as someof the remote,uninhabited regions on the Isthmus. In the field work I had extensive aid from several men whose resourcefulnessand persistencyadded largely to the observations and their names,following, I subscribewith plcasurc.--Mr. Elliott F. Brown, Balboa, Canal Zone; Mr. Albert Horle, Cristobal, Canal Zone; Mr. Ernest Peterkin, United States Navy; Mr. P. T. Sealcy, New York City; Mr. Ezekiel Arnott Smith, Hartford, Conn.;and Mr. JoselibW. Smith,Sisson, Calif. The followinglist locatesthe stations,mentioned in this paper, with reference to the Panama Canal:-- Ancon Hill.--Near the Pacific entrance of the Canal. Balboa.--Near the Pacific entrance of the Canal. Casa Largo.--About 10 miles northeastof the junction of the ChagresRiver and the Canal, on the Atlantic Slope. Corozal.--Near the Pacific entrance of the Canal. Culcbra-ArraijanTrail.--gunning about 6 miles south, on the PacificSlope, from Culebraon the ContinentalDivide. Darien Radio Station.--On the Canal, about 22 miles from the Atlantic entrance,on the Atlantic Slope. -

Table of Contents 4.0 Description of the Physical

TABLE OF CONTENTS 4.0 DESCRIPTION OF THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT............................................ 41 4.1 Geology ................................................................................................. 41 4.1.1 Methodology ........................................................................................ 41 4.1.2 Regional Geological Formations........................................................... 42 4.1.3 Local Geological Units ......................................................................... 47 4.1.3.1 Atlantic Coast .......................................................................... 47 4.1.3.2 Gatun Locks.............................................................................. 48 4.1.3.3 Gatun Lake ............................................................................... 49 4.1.3.4 Culebra Cut ......................................................................... ...410 4.1.3.5 Pacific Locks ...........................................................................411 4.1.3.6 Pacific Coast............................................................................412 4.1.4 Paleontological Resources ...................................................................413 4.1.5 Geotechnical Characterization .............................................................417 4.1.6 Tectonics.............................................................................................421 4.2 Geomorphology ..............................................................................................422 -

Panama As a Crossroads Teacher's Guide

Welcome to Panama as a Crossroads, the educational suite of Before activities that accompanies the exhibition Panamanian Passages! a school trip to We developed these educational resources and opportunities at the exhibition: Visit the exhibition on your own the exhibition site for you and your students to gain a greater before your planned school fi eld trip, or visit the exhibition’s website and read understanding of Panama. Panama is a passage to the world the exhibition brochure to view and re- and a reservoir of biodiversity. Rich in history and culture, it view themes, objects, and important connections to your curriculum: has important links to the history of the United States. Explore www.latino.si.edu. and discover Panama and make connections to your curriculum! Panama as a Crossroads Teacher’s Guide of both sessions, the student worksheet should be completed. The fi nal portion Checklist to consider: of the visit will be a knowledge game that will test the understanding of the Bring one chaperone for every ten students. exhibition using the content presented during the sessions. All visitors must screen their bags at the security desk at the entrance to the building: Pre-visit activities: • Have students write down fi ve to ten S. Dillon Ripley Center. 1100 Jefferson Drive things they know about Panama. SW, Washington D.C. 20560. • Review the exhibition’s website with the students, to further their under- Please note that there are no vending standing of the exhibition. • Make connections with exhibition facilities in this building. themes and your curriculum. • Review the exhibition guide, the map Select the subject areas in the exhibition that of Panama, and the glossary. -

The Panama Canal 75Th Anniversary

Nr/ PANAMA CANAL U-i-^ ^^^^ ^w ^r"'-*- - • «:'• 1! --a""'"!' "lt#;"l ii^'?:^, ^ L«^ riS^x- <t^mi a^ «t29) TP f-« RUlUiWiiIiT?;!!ive AiDum -T'te. 1914-1989 ; PANAIVii^ CANAL COMMISSION i /; BALBOA, REPUBLIC OF PANA^4A ADMINISTRATOR DEJ>UTY ADMINISTRATOR DP. McAuliffe Fernando Manfredo, Jr. DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS :: : Wniic K. Friar The preparation of this special publication by the Office of Public Affairs involved the efforts of many people. Deserving special mention arc the photo lab technicians of the Graphic Branch, the Printing Office, the ?W Technical Resources Center, the Language Services Branch, and the Office of Executive Planning. Photographs are by Arthur Pollack, Kevin Jenkins, Armando DeGracia and Don Goode, who also shot the photo of Miraflores Locks that appears on the cover. Kaye Richey created the 75th Anniversary slogan and adapted the album text from the work of Gil Williams and of Richard Wainio of the Office of Executive Planning. Melvin D. Kennedy, Jr., designed the album and served as photo editor. Jaime Gutierrez created the 75th Anniversary logo and did the album layout. James J. Reid and Jos6 S. Alegria Ch. of the Printing Office were invaluable in the layout and typesetting process. An Official publication of the Panama Canal Commission, April 1989 <«•-!*»'•* J-V-y I m epuTu Administrator on the 75th Anniversary of the Panasr '\ eventy-five years ago, the world hailed the monumental engineeriiip^^^?x'emi3nt of the V> century. The opening of the Panama Canal on August 15, 1914, fulfillecJ ih»; ccnturies-olH . .^gjWEFt^" dream of uniting the world's two great oceans and established a new li.'k 'n the v;orld . -

The Panama Canal Review Jungle Growth Being Cleared Away

UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARIES Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Florida, George A. Smathers Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/panamacanalrevienov16pana A^ NOVEMBER 1966 Governor-President Robert D. Kerr, Press OfiBcer Robert J. Fleming, Jr., Publications Editors H. R. Parfitt, Lieutenant Governor ^^^b. Morgan E. Goodwin and Tomas A. Cupas Editorial Assistants Frank A. Baldwin Eunice Richard, Tobi Bittel, Fannie P. Official Panama Canal Publication Hernandez, and T. Panama Canal Information Officer Published quarterly at Balboa Heights, C.Z. Jose Tunon Printed at the Printing Plant, La Boca, C.Z. Review articles may be reprinted in full or part without further clearance. Credit to the Review will be appreciated. Distributed free of charge to all Panama Canal Employees. Subscriptions, SI a year: airmail S2 a year; mail and back copies (regular mail), 25 cents each cAbout Our Cover PHOTOGRAPHED AT THE ruins of the Cathedral of wearing typical Indian dress. The two at either end are i>ld«E^aD^a and wearing the costumes which portray wearing the dress of the guaymi Indians who inhabit the the rich folklore of Panama are members of the conjunto high mountains of Veraguas and Chiriqui. Next to them '^Wiythms of Bgnama, a dance group directed by Professor and the two in the center are cuna Indians from the Petita Escobar of Panama City. San Bias Islands, the tribe never conquered by the Standing on top of tlie ruins are the "dirty devils," Spanish and the members of which still hve and dress wearing trousers and shirts of rough muslin dyed red and as they did before Columbus' discovery of America. -

Panama Canal Manmade Lake — “Too Big for Photo” Wired One Photographer

Bridge Between Worlds CONSTRUCTION EVENT OF THE ceNTURY istory Even before its opening, reporters, photojournalists, adventurers H and the curious came from around the world to witness this colossal undertaking. What they found was almost beyond description: Locks with walls 1,000-feet long, gates seven-feet thick, the world’s largest Teddy Roosevelt Admirers poured into the locks for a close-up look. Panama Canal manmade lake — “too big for photo” wired one photographer. Canal Panama Early efforts A flood of water As early as the days of Columbus, man was set on finding a sea-level To provide the perpetual water supply necessary to operate the locks, an shortcut through the American landmass. But not until Frenchman earthen dam was built across the Chagres Ferdinand de Lesseps, fresh from his triumph of building the Suez Canal River, causing flooding and creating in 1879, did anyone make a serious attempt. Long story short: The project Gatún Lake (at the time, the world’s was poorly managed, underfinanced, and in 1889 the French company largest artificial lake). In the process, hilltops became islands, as in the case went bankrupt. Clearly, an engineering project of this magnitude was too of Barro Colorado Island, a lush living much for a private company. This was a job for a nation. laboratory for the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. Enter the United States On time, under budget In 1902 President Theodore Roosevelt revived the dream. The United States In 1913, a full year ahead of schedule and purchased the French holdings in Panama for a record $40 million. -

Panama´S Canal Zone: a Relaxed and Easy Tour

Victor Emanuel Nature Tours Panama´s Canal Zone: A relaxed and easy tour November 12-18, 2017 White-necked Jacobin. Florisuga mellivora. David Ascanio Leaders: David Ascanio & Eliécer Rodriguez (Benny Wilson – Full day Panama City) Compiled by David Ascanio Victor Emanuel Nature Tours, inc. 2525 Wallington Drive, Suite 1003 Austin, TX 78746 www.ventbird.com The silent night in the peaceful town of Gamboa was followed by a wild blast of birds at dawn near the lodge. What a way to start our Panama Canal tour! The bird feeder was the first step to identify some of the common and colorful species and that included Plain-colored, Blue-gray, Palm, Crimson-backed and Golden-hooded Tanagers. In addition to this kaleidoscope of colors we also saw Red-legged and Shinning Honeycreeper, Orange-chinned Parakeet and Buff-throated Saltator. As the morning warmed-up we walked in the streets of Gamboa and added Common Tody Flycatcher, Baltimore Oriole, Gray-headed Chachalacas, Gray-lined Hawk and three Short-tailed Hawks in flight. A slow afternoon (due to the rain) gave us the chance to have close views of Gartered Trogon and a female Blue Cotinga. The second day was to explore the riverine forest of the Chagres river and also Lake Gatún, along the Panama Canal. These locations gave us the opportunity to add Lesser Yellow-headed Vulture, Greater Ani, Common Black Hawk, Black-bellied Whistling-Duck, Snail Kite, Rufous Motmot, Keel-billed Toucan, Purple Gallinule, Mangrove Swallow, Fasciated Antshirke, Green Kingfisher and Limpkin to our list. We also saw several waterbirds and three species of terns. -

Some Historical Aspects on the Hydraulic Design of the Gatun Spillway in the Panama Canal

8th IAHR ISHS 2020 Santiago, Chile, May 12th to 15th 2020 DOI: 10.14264/uql.2020.609 Some historical aspects on the hydraulic design of the Gatun Spillway in the Panama Canal A.V. Bal1, F. Re2, M.R. Lapetina2 & N. Badano2 1Panama Canal Authority Balboa, Panama 2Stantec Buenos Aires, Argentina E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The Gatun spillway in the Panama Canal is built on top of the sea-level canal project, which was excavated between 1881 and 1887 by the Universal Company of the Interoceanic Canal, of France. The project was changed in October 1887 to a lock canal project. The design of the Gatun Spillway was developed between 1909 and 1911 by the Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC), an organization which reported directly to the United States Secretary of War, and which had the support of some of the best engineering minds working at the best universities, engineering companies and government institutions of the United States and Europe. A 1:32 scale physical model was used to aid in the spillway design. The spillway was completed in 1913 and the Panama Canal began operating on August 15th, 1914. This paper presents some engineering and historical aspects of the hydraulic design of the Gatun Spillway. The spillway design hydrograph and the methodology used to estimate the number of spillway gates required is contrasted to the current engineering practice. A detailed hydraulic engineering study was performed for the spillway between 2011 and 2013, in order to evaluate its hydraulic performance and to determine its discharge rating curve, using the OpenFoam CFD model and a physical model at a scale of 1:40. -

THE PANAMA CANAL REVIEW January 2, 1953

S^ «//A* Panama Canal Museum ^ ^ Vol. 3, No. 6 BALBOA HEIGHTS, CANAL ZONE, JANUARY 2, 1953 5 cents PLANS ANNOUNCED FOR PREMIUM GRADE GASOLINE TO BE SOLD AT ZONE RETAIL SERVICE STATIONS EVENTFUL 1952 Various Alterations Needed For Handling Sale Of Two Grades The sale of high-test gasoHne will be started at the Canal's retail gas stations as soon as the necessary arrangements can be made and a supply of premium gasoline can be obtained. An interval of about three months may elapse before the first premium gi-ade gas is available since about 60 days are required for deliveries after orders are placed and minor alterations are required at the tank farms and at the service stations. The high-test gas will be on sale at all retail stations except at Gatun and Pedro \See page A HIGHLIGHT ot the past year was the arrival of Governor Seybold to begin his tenn of office Miguel where additional m There have been few years in the Canal's tion in Ancon, Balboa, Diablo Heights, Paraiso, Cardenas, Silver City, and Marga- history to match 1952 for the constant stream New Policy Is Announced rita. In addition the Maintenance Division of news of more than passing interest to was assigned quarters construction work Applications employees and their families. There was totaling over SI, 000, 000 and bids were On Quarters scarcely a ireek of the past 52 which was not awarded for $325,000 worth of native lum- ber for the building program. The bids for Applications for assignments to U. -

A Sip of the Chagres

A SIP OF THE CHAGRES THE LAND OF THE COCOANUT-TREE From "Panama Patchwork" (original spelling) James Stanley Gilbert 1853-1906 AWAY down south in the Torrid Zone, North latitude nearly nine, Where the eight months' pour once past and o'er, The sun four months doth shine; Where 'tis eighty-six the year around, And people rarely agree; Where the plaintain grows and the hot wind blows, Lies the Land of the Cocoanut Tree. Tis the land where all the insects breed That live by bite and sting; Where the birds are quite winged rainbows bright, Tho' seldom one doth sing! Here radiant flowers and orchids thrive And bloom perennially- All beauteous, yes - but odorless! In the Land of the Cocoanut-Tree. 'Tis a land profusely rich, 'tis said, In mines of yellow gold, That, of claims bereft, the Spaniards left In the cruel days of old! And many a man hath lost his life That treasure-trove to see, Or doth agonize with steaming eyes In the Land of the Cocoanut-Tree! 'Tis a land that still with potent charm And wondrous, lasting spell With mighty thrall enchanteth all Who long within it dwell; 'Tis, a land where the Pale Destroyer waits And watches eagerly; 'Tis, in truth, but a breath from life to death, In the Land of the Cocoanut-Tree. 1 Then, go away if you have to go Then, go away if you will! To again return, you will always yearn While the lamp is burning still! You've drank the Chagres water And the mango eaten free, And, strange tho' it seems, 'twill haunt your dreams -- This land of the Cocoanut-tree. -

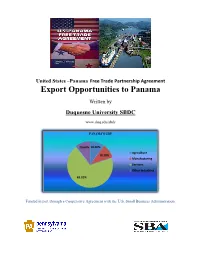

Export Opportunities to Panama Written By

United States –Panama Free Trade Partnership Agreement Export Opportunities to Panama Written by Duquesne University SBDC www.duq.edu/sbdc PANAMA’S GDP 10.60% 10.00% Agriculture 10.20% Manufacturing Services Other Industries 69.20% Funded in part through a Cooperative Agreement with the U.S. Small Business Administration. Table of Contents Section One .................................................................................................................................. IV A) Panama Market ..................................................................................................................... IV 1) Economy………………..............................................................................................IV 2) Top Imports and Top International Partners…………………………………………VI 3) Industry Sectors and Future Growth Areas .................................... …………………IX Secton Two………………………...………………………………………………………….XIV B) Free Trade Agreement…………………………………………………………………..XIV Section Three…………………………………………………………………..…………...XVIII B) Top Industries in Panama………………………………………………………………XVIII 1) Construction a) Market......………………………………………………………………………..XVIII b) Key Player………..…………………….…………………………………….........XX c) Regulatory Issues.……………….………...……………………………..……...XXIV d) Projects & Opportunities……….………………………………………………...XXV e) Supply Chain Strategy…...………………………………………………………XXVI 2) Computers, Parts, Telecommunications Equipment and Services a) Market.…………………………………………………………………….…...XXVIII b) Key Players…………….………………………………………………………...XXIX c) RegulatoryIssues……………………….....………………………………….....XXXII