Implementing the Withdrawal Agreement: Citizens' Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Law and Brexit 22 February – 3 March 2021

Public Law and Brexit 22 February to 3 March 2021 Public Law and Brexit 22 February – 3 March 2021 DELEGATE PACK* Contents Page Agenda and speaker biographies 4-13 Delegated powers and statutory instruments (23 February, 9:00-10:30) 14 Plus ça change? Brexit and the flaws of the delegated legislation system, by Alexandra Sinclair and Dr Joe Tomlinson Environment (25 February, 14:00-15:30) 54 The agreement on the future relationship: a first analysis, by Marley Morris Immigration and the EUSS (1 March, 9:00-10:30) What is the law that applies to EU nationals at the end of the 67 Brexit transition period? The 3million submission to the Independent Monitoring Authority 79 What to expect for EU Citizens’ Rights in 2021 125 *Please note this pack may be updated throughout the conference. A final version will be circulated with all presentations and recordings after the fact. 4 Agenda Monday 22 February 9:00-9.10: Introduction Jo Hickman, Director and Alison Pickup, Legal Director, Public Law Project 9.10-10.10: The enforceable provisions of the Withdrawal Agreement Chair: Alison Pickup, PLP Professor Catherine Barnard, Cambridge University Faculty of Law David Heaton, Brick Court Chambers Leonie Hirst, Doughty Street Chambers 14.00-15.30: What is retained EU law? Chair: Alison Pickup, PLP Tim Buley QC, Landmark Chambers Professor Tarunabh Khaitan, Oxford University Emma Mockford, Brick Court Chambers James Segan QC, Blackstone Chambers Tuesday 23 February 9.00-10.30: Delegated powers and statutory instruments Chair: Alison Pickup, PLP -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

FDN-274688 Disclosure

FDN-274688 Disclosure MP Total Adam Afriyie 5 Adam Holloway 4 Adrian Bailey 7 Alan Campbell 3 Alan Duncan 2 Alan Haselhurst 5 Alan Johnson 5 Alan Meale 2 Alan Whitehead 1 Alasdair McDonnell 1 Albert Owen 5 Alberto Costa 7 Alec Shelbrooke 3 Alex Chalk 6 Alex Cunningham 1 Alex Salmond 2 Alison McGovern 2 Alison Thewliss 1 Alistair Burt 6 Alistair Carmichael 1 Alok Sharma 4 Alun Cairns 3 Amanda Solloway 1 Amber Rudd 10 Andrea Jenkyns 9 Andrea Leadsom 3 Andrew Bingham 6 Andrew Bridgen 1 Andrew Griffiths 4 Andrew Gwynne 2 Andrew Jones 1 Andrew Mitchell 9 Andrew Murrison 4 Andrew Percy 4 Andrew Rosindell 4 Andrew Selous 10 Andrew Smith 5 Andrew Stephenson 4 Andrew Turner 3 Andrew Tyrie 8 Andy Burnham 1 Andy McDonald 2 Andy Slaughter 8 FDN-274688 Disclosure Angela Crawley 3 Angela Eagle 3 Angela Rayner 7 Angela Smith 3 Angela Watkinson 1 Angus MacNeil 1 Ann Clwyd 3 Ann Coffey 5 Anna Soubry 1 Anna Turley 6 Anne Main 4 Anne McLaughlin 3 Anne Milton 4 Anne-Marie Morris 1 Anne-Marie Trevelyan 3 Antoinette Sandbach 1 Barry Gardiner 9 Barry Sheerman 3 Ben Bradshaw 6 Ben Gummer 3 Ben Howlett 2 Ben Wallace 8 Bernard Jenkin 45 Bill Wiggin 4 Bob Blackman 3 Bob Stewart 4 Boris Johnson 5 Brandon Lewis 1 Brendan O'Hara 5 Bridget Phillipson 2 Byron Davies 1 Callum McCaig 6 Calum Kerr 3 Carol Monaghan 6 Caroline Ansell 4 Caroline Dinenage 4 Caroline Flint 2 Caroline Johnson 4 Caroline Lucas 7 Caroline Nokes 2 Caroline Spelman 3 Carolyn Harris 3 Cat Smith 4 Catherine McKinnell 1 FDN-274688 Disclosure Catherine West 7 Charles Walker 8 Charlie Elphicke 7 Charlotte -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Tuesday Volume 678 30 June 2020 No. 78 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 30 June 2020 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2020 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 133 30 JUNE 2020 134 Wendy Morton: That is a really important point. The House of Commons Prime Minister has made it clear that equitable access is an integral part of the UK’s approach to vaccine Tuesday 30 June 2020 development and distribution. Only last weekend, he emphasised how all the world’s leaders have a moral duty to ensure that covid-19 vaccines are truly available The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock to all. That is why the UK has contributed more than £313 million of UK aid to CEPI, the COVID-19 PRAYERS Therapeutics Accelerator, the Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator, and the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics. We have also committed £1.65 billion [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] to Gavi over five years to strengthen immunisation for Virtual participation in proceedings commenced (Order, vaccine preventable disease in vulnerable countries. 4 June). Andrew Jones: Around the world, there are more than [NB: [V] denotes a Member participating virtually.] 100 programmes to develop a coronavirus vaccine. Can my hon. Friend confirm that our global diplomatic presence is assisting UK companies and universities to Oral Answers to Questions participate in those programmes, basically by using their local networks to highlight the significant expertise that the UK can contribute, but also vice versa to identify where those contacts can contribute to UK-based FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH OFFICE programmes, because this is truly a global effort? The Secretary of State was asked— Wendy Morton: Yes, our overseas network is working actively around the globe, particularly through our Covid-19 Vaccine world-leading science and innovation network. -

An English Song Line

An English Songline by JAG Maw October 1986, a steamy college cellar somewhere under Cambridge. Lighting way low, amps buzzing gently, student chatter picked up by the stage mics, PA system on the edge of feedback. I was sitting on a monitor with a post-gig pint and talking rubbish to anyone prepared to listen. A bloke sidled up to Join the chat. I was immediately impressed by his leather Jacket. Not some chained-up bogus biker Job: this one had lapels. Like David Sylvian’s on the Quiet Life cover, only black. Very cool. But hang on a minute. Is that? I squinted. Out of each sleeve poked the tiny, whiskered and unmistakable face of a rat. Each would tip-toe occasionally down a thumb to sniff the air, have a rather pleased sip of beer and then disappear back into its sleeve. A Londoner taught to identify these creatures with the Plague, I raised an eyebrow. The rats were introduced to me as Sly and Robbie, and leather Jacket bloke introduced himself as a guitarist. “I think you need a new one,” he said. A new guitarist? It was hard to disagree. As the singer, I had decided that my Job was to write inscrutable lyrics and then deliver them with unshakable conviction. Musically, however, I relied on the honourable excuses of punk rock. My guitar tended to run out of ideas after five chords (that’s including the minors), and then turn into a stage prop. I went off to confer with the other band members, and told them about leather Jacket guitarist and Sly and Robbie. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Tuesday Volume 699 20 July 2021 No. 37 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 20 July 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 789 20 JULY 2021 790 journalists are rounded up, pro-democracy protesters House of Commons are arrested and 1 million Uyghurs are incarcerated in detention camps. In October, before he was overruled Tuesday 20 July 2021 by the Chancellor and the Prime Minister, he said that there comes a point where sport and politics cannot be The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock separated. When is that point? Dominic Raab: The hon. Lady knows that the PRAYERS participation of any national team in the Olympics is a matter for the British Olympic Association, which is [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] required, as a matter of law under the International Virtual participation in proceedings commenced (Orders, Olympic Committee regulations, to take those decisions 4 June and 30 December 2020). independently. We have led the international response [NB: [V] denotes a Member participating virtually.] on Xinjiang, and also on Hong Kong. Of course, as we have said, we will consider the level of Government representation at the winter Olympics in due course. Oral Answers to Questions Lisa Nandy: While the Foreign Secretary continues to duck the question, the Chinese Government have raised the stakes.Yesterday,he admitted that China was responsible FOREIGN, COMMONWEALTH AND for the Microsoft Exchange hack, which saw businesses’ DEVELOPMENT OFFICE data stolen and hackers demanding millions of pounds in ransom. -

Open PDF 588KB

House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Formal Minutes Session 2017–19 The Home Affairs Committee The Home Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Home Office and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon Yvette Cooper MP (Chair, Labour, Normanton, Pontefract and Castleford) Rehman Chishti MP (Conservative, Gillingham and Rainham) Sir Christopher Chope MP (Conservative, Christchurch) Janet Daby MP (Labour, Lewisham East) Stephen Doughty MP (Labour (Co-op), Cardiff South and Penarth) Chris Green MP (Conservative, Bolton West) Kate Green MP (Labour, Stretford and Urmston) Tim Loughton MP (Conservative, East Worthing and Shoreham) Stuart C. McDonald MP (Scottish National Party, Cumbernauld, Kilsyth & Kirkintilloch East) Toby Perkins MP (Labour, Chesterfield) Douglas Ross MP (Conservative, Moray) The following Members were members of the Committee during the Session: Preet Kaur Gill MP (Labour (Co-op), Birmingham, Edgbaston) Sarah Jones MP (Labour, Croydon Central) Kirstene Hair MP (Conservative, Angus) Rt Hon Esther McVey MP (Conservative, Tatton) Alex Norris MP (Labour (Co-op), Nottingham North) Will Quince MP (Conservative, Colchester) Naz Shah MP (Labour, Bradford West) John Woodcock MP (Independent, Barrow and Furness) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/homeaffairscom. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Tuesday Volume 687 19 January 2021 No. 162 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 19 January 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 753 19 JANUARY 2021 754 Chris Law (Dundee West) (SNP) [V]: Global poverty House of Commons has risen for the first time in more than 20 years, and by the end of this year, it is estimated that there will be Tuesday 19 January 2021 more than 150 million people in extreme poverty.Against that backdrop, the UK Government recklessly abolished the Department for International Development, they The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock are reneging on their 0.7% of GNI commitment, and they do not even mention eradicating poverty in the seven global challenges that UK aid is to be focused on. PRAYERS Can the Minister explicitly commit to eradicating poverty within the new official development assistance framework, rather than pursuing inhumane and devastating cuts as [MR SPEAKER ] in the Chair part of the Prime Minister’s little Britain vanity project? Virtual participation in proceedings continued (Order, 4 June and 30 December 2020). James Duddridge: The hon. Gentleman knows that [NB: [V] denotes a Member participating virtually.] we share a passion for international development. These specific targets do aim to alleviate and eradicate poverty, but the causes of poverty and the solutions to it are complex. That is why the merger of the Departments Oral Answers to Questions works, dealing with development and diplomacy alongside one another to overcome the scourge of poverty, which, sadly, has increased not decreased as a result of covid. -

Daily Report Wednesday, 26 May 2021 CONTENTS

Daily Report Wednesday, 26 May 2021 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 26 May 2021 and the information is correct at the time of publication (07:06 P.M., 26 May 2021). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 6 CABINET OFFICE 14 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Civil Service: Conditions of INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 6 Employment 14 Climate Change 6 Emergencies: Mobile Phones 15 Company Liquidations: West Foreign Investment in UK: Yorkshire 7 Assets 15 Conditions of Employment 7 UK Trade with EU: Customs 16 Consumers: Subscriptions 7 DEFENCE 16 Coronavirus Business Armed Forces: Deployment 16 Interruption Loan Scheme 8 Armed Forces: Technology 16 Electricity Interconnectors: Army 17 Portsmouth 9 Army: Employment 17 Employment: Loneliness 9 Defence Cyber Academy 17 Energy 10 Defence Cyber Academy: Energy: Meters 10 Finance 18 Energy: Public Consultation 10 Defence Cyber Academy: Greenhouse Gas Emissions 11 Location 18 Hospitality Industry: Staff 11 Joint Strike Fighter Aircraft: OneWeb 11 Procurement 18 Post Offices: ICT 12 Shipbuilding 18 Retail Sector Council: Xinjiang 12 Veterans: Northern Ireland 19 Space Debris 13 DIGITAL, CULTURE, MEDIA AND SPORT 19 Weddings: Coronavirus 13 Broadband: Southport 19 Wind Power: Investment 14 Broadband: Standards 19 Digital Technology: Disadvantaged 20 Football Index 21 Food: Marketing 42 Gambling: Children 21 Pet Theft Task Force 43 Internet: Freedom of Speech -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Friday Volume 632 1 December 2017 No. 61 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Friday 1 December 2017 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2017 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 585 1 DECEMBER 2017 586 Glindon, Mary Merriman, Huw House of Commons Goodman, Helen Morden, Jessica Grady, Patrick Morris, Grahame Green, Kate Morton, Wendy Friday 1 December 2017 Greenwood, Lilian Murray, Ian Griffith, Nia Norris, Alex The House met at half-past Nine o’clock Grogan, John Onn, Melanie Gwynne, Andrew Peacock, Stephanie Gyimah, Mr Sam Pennycook, Matthew PRAYERS Haigh, Louise Perry, Claire The Chairman of Ways and Means took the Chair as Hall, Luke Philp, Chris Deputy Speaker (Standing Order No. 3). Hamilton, Fabian Pidcock, Laura Hancock, rh Matt Pincher, Christopher Graham P. Jones (Hyndburn) (Lab): I beg to move, Hardy, Emma Platt, Jo That the House sit in private. Harper, rh Mr Mark Pollard, Luke Question put forthwith (Standing Order No. 163). Harris, Carolyn Prentis, Victoria Harris, Rebecca Rashid, Faisal The House divided: Ayes 0, Noes 169. Healey, rh John Rayner, Angela Division No. 51] [9.34 am Heaton-Harris, Chris Reeves, Ellie Hendrick, Mr Mark Rimmer, Ms Marie AYES Hill, Mike Shah, Naz Hillier, Meg Skidmore, Chris Tellers for the Ayes: Hollinrake, Kevin Smeeth, Ruth Lucy Allan and Hollobone, Mr Philip Smith, Cat Mr Jacob Rees-Mogg Howarth, rh Mr George Smith, Chloe Huq, Dr Rupa Smith, Eleanor -

Ministerial Departments CABINET OFFICE March 2021

LIST OF MINISTERIAL RESPONSIBILITIES Including Executive Agencies and Non- Ministerial Departments CABINET OFFICE March 2021 LIST OF MINISTERIAL RESPONSIBILITIES INCLUDING EXECUTIVE AGENCIES AND NON-MINISTERIAL DEPARTMENTS CONTENTS Page Part I List of Cabinet Ministers 2-3 Part II Alphabetical List of Ministers 4-7 Part III Ministerial Departments and Responsibilities 8-70 Part IV Executive Agencies 71-82 Part V Non-Ministerial Departments 83-90 Part VI Government Whips in the House of Commons and House of Lords 91 Part VII Government Spokespersons in the House of Lords 92-93 Part VIII Index 94-96 Information contained in this document can also be found on Ministers’ pages on GOV.UK and: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/government-ministers-and-responsibilities 1 I - LIST OF CABINET MINISTERS The Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP Prime Minister; First Lord of the Treasury; Minister for the Civil Service and Minister for the Union The Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP Chancellor of the Exchequer The Rt Hon Dominic Raab MP Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs; First Secretary of State The Rt Hon Priti Patel MP Secretary of State for the Home Department The Rt Hon Michael Gove MP Minister for the Cabinet Office; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster The Rt Hon Robert Buckland QC MP Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice The Rt Hon Ben Wallace MP Secretary of State for Defence The Rt Hon Matt Hancock MP Secretary of State for Health and Social Care The Rt Hon Alok Sharma MP COP26 President Designate The Rt Hon -

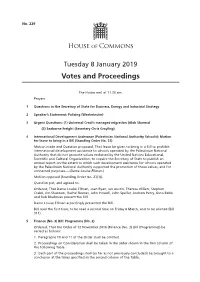

Votes and Proceedings 8 January 2019

No. 229 Tuesday 8 January 2019 Votes and Proceedings The House met at 11.30 am. Prayers 1 Questions to the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy 2 Speaker’s Statement: Policing (Westminster) 3 Urgent Questions: (1) Universal Credit: managed migration (Alok Sharma) (2) Seaborne Freight (Secretary Chris Grayling) 4 International Development Assistance (Palestinian National Authority Schools): Motion for leave to bring in a Bill (Standing Order No. 23) Motion made and Question proposed, That leave be given to bring in a Bill to prohibit international development assistance to schools operated by the Palestinian National Authority that do not promote values endorsed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; to require the Secretary of State to publish an annual report on the extent to which such development assistance for schools operated by the Palestinian National Authority supported the promotion of those values; and for connected purposes.—(Dame Louise Ellman.) Motion opposed (Standing Order No. 23(1)). Question put, and agreed to. Ordered, That Dame Louise Ellman, Joan Ryan, Ian Austin, Theresa Villiers, Stephen Crabb, Jim Shannon, Rachel Reeves, John Howell, John Spellar, Andrew Percy, Guto Bebb and Bob Blackman present the Bill. Dame Louise Ellman accordingly presented the Bill. Bill read the first time; to be read a second time on Friday 8 March, and to be printed (Bill 311). 5 Finance (No. 3) Bill: Programme (No. 2) Ordered, That the Order of 12 November 2018 (Finance (No. 3) Bill (Programme)) be varied as follows: 1. Paragraphs 10 and 11 of the Order shall be omitted.