An English Song Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Law and Brexit 22 February – 3 March 2021

Public Law and Brexit 22 February to 3 March 2021 Public Law and Brexit 22 February – 3 March 2021 DELEGATE PACK* Contents Page Agenda and speaker biographies 4-13 Delegated powers and statutory instruments (23 February, 9:00-10:30) 14 Plus ça change? Brexit and the flaws of the delegated legislation system, by Alexandra Sinclair and Dr Joe Tomlinson Environment (25 February, 14:00-15:30) 54 The agreement on the future relationship: a first analysis, by Marley Morris Immigration and the EUSS (1 March, 9:00-10:30) What is the law that applies to EU nationals at the end of the 67 Brexit transition period? The 3million submission to the Independent Monitoring Authority 79 What to expect for EU Citizens’ Rights in 2021 125 *Please note this pack may be updated throughout the conference. A final version will be circulated with all presentations and recordings after the fact. 4 Agenda Monday 22 February 9:00-9.10: Introduction Jo Hickman, Director and Alison Pickup, Legal Director, Public Law Project 9.10-10.10: The enforceable provisions of the Withdrawal Agreement Chair: Alison Pickup, PLP Professor Catherine Barnard, Cambridge University Faculty of Law David Heaton, Brick Court Chambers Leonie Hirst, Doughty Street Chambers 14.00-15.30: What is retained EU law? Chair: Alison Pickup, PLP Tim Buley QC, Landmark Chambers Professor Tarunabh Khaitan, Oxford University Emma Mockford, Brick Court Chambers James Segan QC, Blackstone Chambers Tuesday 23 February 9.00-10.30: Delegated powers and statutory instruments Chair: Alison Pickup, PLP -

The Temenos Academy

THE TEMENOS ACADEMY “John Michell 1933-2009” Author: Joscelyn Godwin Source: Temenos Academy Review 12 (2009) pp. 250-253 Published by The Temenos Academy Copyright © Joscelyn Godwin, 2009 The Temenos Academy is a Registered Charity in the United Kingdom www.temenosacademy.org 250-253 Michell Godwin:Layout 1 3/11/09 13:30 Page 250 John Michell (1933–2009) Joscelyn Godwin ‘ ut how shall we bury you?’ asked Crito. ‘In any way you like,’ said B Socrates, ‘if you can catch me, and I do not escape you.’ Who could possibly catch John Michell, alive or dead? The Church of England, which buried him, or the Glastonbury pagans who cele - brated his birthdays and wedding? The Forteans on both sides of the Atlantic, knowing who was his favourite philosopher after Plato? The pilgrims whom he fluently guided around Holy Russia? The Old Eton - ians and the caste to which he was born? The old rock stars who knew him as pictured in David Bailey’s book of Sixties portraits, Goodbye Baby and Amen? Ufologists, honoured by his very first book? Ley hunters and earth mysteries folk? Students of crop-circles and other anomalous pheno mena? Sacred geometers and ancient metrologists? Grown-up children who see through every emperor’s new clothes? By common standards John’s life was mildly eccentric, his notions very peculiar. For one thing, he was nocturnal. The flat at the top of his Notting Hill house seemed a philosopher’s eyrie as one watched the sun setting over London’s roofscape. Then as the candles were lit, the curtains drawn, it was more of a hobbit smial, or Badger’s burrow. -

Iain Sinclair and the Psychogeography of the Split City

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Iain Sinclair and the psychogeography of the split city https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40164/ Version: Full Version Citation: Downing, Henderson (2015) Iain Sinclair and the psychogeog- raphy of the split city. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email 1 IAIN SINCLAIR AND THE PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY OF THE SPLIT CITY Henderson Downing Birkbeck, University of London PhD 2015 2 I, Henderson Downing, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract Iain Sinclair’s London is a labyrinthine city split by multiple forces deliriously replicated in the complexity and contradiction of his own hybrid texts. Sinclair played an integral role in the ‘psychogeographical turn’ of the 1990s, imaginatively mapping the secret histories and occulted alignments of urban space in a series of works that drift between the subject of topography and the topic of subjectivity. In the wake of Sinclair’s continued association with the spatial and textual practices from which such speculative theses derive, the trajectory of this variant psychogeography appears to swerve away from the revolutionary impulses of its initial formation within the radical milieu of the Lettrist International and Situationist International in 1950s Paris towards a more literary phenomenon. From this perspective, the return of psychogeography has been equated with a loss of political ambition within fin de millennium literature. -

Fighting the Mythos in the Western Saxon Kingdom at the Turn of the First Millennium

1 Cthulhu Dark Ages - Pagan Call Kevin Anderson and Stéphane Gesbert PAGAN CALL Fighting the Mythos in the Western Saxon Kingdom at the Turn of the First Millennium A Campaign for Call of Cthulhu “Dark Ages” by Kevin Anderson and Stéphane Gesbert Email [email protected] www http://ad1000.cjb.net/ Copyright © 1997-2001, 2002 Kevin Anderson and Stéphane Gesbert Kevin Anderson and Stéphane Gesbert Pagan Call: General Background 2 Copyright © 1997-2001, 2002 Kevin Anderson and Stéphane Gesbert 3 Cthulhu Dark Ages - Pagan Call Kevin Anderson and Stéphane Gesbert Pagan Call: General Background “AD 1020. This year went the king [Knute] to Assingdon; with Earl Thurkyll, and Archbishop Wulfstan, and other bishops, and also abbots, and many monks with them; and he ordered to be built there a minster of stone and lime, for the souls of the men who were there slain, and gave it to his own priest, whose name was Stigand; and they consecrated the minster at Assingdon. And Ethelnoth the monk, who had been dean at Christ's church, was the same year on the ides of November consecrated Bishop of Christ's church by Archbishop Wulfstan” – The Saxon Chronicles The following series of linked scenarios – “chapters” - Seth began to make his plans. Taking human form by way form a campaign set in the southeast of England around of magical deception, and borrowing a human name – 1020 AD. With minor modifications, the campaign can be Stigand (pronounce Stig’n), Seth returned to the waking shifted to any year of the Danish raid period, 980-1016 world. -

Sacred Places Europe: 108 Destinations

Reviews from Sacred Places Around the World “… the ruins, mountains, sanctuaries, lost cities, and pilgrimage routes held sacred around the world.” (Book Passage 1/2000) “For each site, Brad Olsen provides historical background, a description of the site and its special features, and directions for getting there.” (Theology Digest Summer, 2000) “(Readers) will thrill to the wonderful history and the vibrations of the world’s sacred healing places.” (East & West 2/2000) “Sites that emanate the energy of sacred spots.” (The Sunday Times 1/2000) “Sacred sites (to) the ruins, sanctuaries, mountains, lost cities, temples, and pilgrimage routes of ancient civilizations.” (San Francisco Chronicle 1/2000) “Many sacred places are now bustling tourist and pilgrimage desti- nations. But no crowd or souvenir shop can stand in the way of a traveler with great intentions and zero expectations.” (Spirituality & Health Summer, 2000) “Unleash your imagination by going on a mystical journey. Brad Olsen gives his take on some of the most amazing and unexplained spots on the globe — including the underwater ruins of Bimini, which seems to point the way to the Lost City of Atlantis. You can choose to take an armchair pilgrimage (the book is a fascinating read) or follow his tips on how to travel to these powerful sites yourself.” (Mode 7/2000) “Should you be inspired to make a pilgrimage of your own, you might want to pick up a copy of Brad Olsen’s guide to the world’s sacred places. Olsen’s marvelous drawings and mysterious maps enhance a package that is as bizarre as it is wonderfully acces- sible. -

A Critical Study of the Novels of John Fowles

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 1986 A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE NOVELS OF JOHN FOWLES KATHERINE M. TARBOX University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation TARBOX, KATHERINE M., "A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE NOVELS OF JOHN FOWLES" (1986). Doctoral Dissertations. 1486. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1486 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE NOVELS OF JOHN FOWLES BY KATHERINE M. TARBOX B.A., Bloomfield College, 1972 M.A., State University of New York at Binghamton, 1976 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English May, 1986 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. This dissertation has been examined and approved. .a JL. Dissertation director, Carl Dawson Professor of English Michael DePorte, Professor of English Patroclnio Schwelckart, Professor of English Paul Brockelman, Professor of Philosophy Mara Wltzllng, of Art History Dd Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. I ALL RIGHTS RESERVED c. 1986 Katherine M. Tarbox Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. to the memory of my brother, Byron Milliken and to JT, my magus IV Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Sacred Places Europe: 108 Destinations

Reviews from Sacred Places Around the World “… the ruins, mountains, sanctuaries, lost cities, and pilgrimage routes held sacred around the world.” (Book Passage 1/2000) “For each site, Brad Olsen provides historical background, a description of the site and its special features, and directions for getting there.” (Theology Digest Summer, 2000) “(Readers) will thrill to the wonderful history and the vibrations of the world’s sacred healing places.” (East & West 2/2000) “Sites that emanate the energy of sacred spots.” (The Sunday Times 1/2000) “Sacred sites (to) the ruins, sanctuaries, mountains, lost cities, temples, and pilgrimage routes of ancient civilizations.” (San Francisco Chronicle 1/2000) “Many sacred places are now bustling tourist and pilgrimage desti- nations. But no crowd or souvenir shop can stand in the way of a traveler with great intentions and zero expectations.” (Spirituality & Health Summer, 2000) “Unleash your imagination by going on a mystical journey. Brad Olsen gives his take on some of the most amazing and unexplained spots on the globe — including the underwater ruins of Bimini, which seems to point the way to the Lost City of Atlantis. You can choose to take an armchair pilgrimage (the book is a fascinating read) or follow his tips on how to travel to these powerful sites yourself.” (Mode 7/2000) “Should you be inspired to make a pilgrimage of your own, you might want to pick up a copy of Brad Olsen’s guide to the world’s sacred places. Olsen’s marvelous drawings and mysterious maps enhance a package that is as bizarre as it is wonderfully acces- sible. -

Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs Vol.4: S - Z

Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs vol.4: S - Z © Neuss / Germany: Bruno Buike 2017 Buike Music and Science [email protected] BBWV E30 Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs - vol.4: S - Z Neuss: Bruno Buike 2017 CONTENT Vol. 1 A-D 273 p. Vol. 2 E-K 271 p. Vol. 3 L-R 263 p. Vol. 4 S-Z 239 p. Appr. 21.000 title entries - total 1046 p. ---xxx--- 1. Dies ist ein wissenschaftliches Projekt ohne kommerzielle Interessen. 2. Wer finanzielle Forderungen gegen dieses Projekt erhebt, dessen Beitrag und Name werden in der nächsten Auflage gelöscht. 3. Das Projekt wurde gefördert von der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Sozialamt Neuss. 4. Rechtschreibfehler zu unterlassen, konnte ich meinem Computer trotz jahrelanger Versuche nicht beibringen. Im Gegenteil: Das Biest fügt immer wieder neue Fehler ein, wo vorher keine waren! 1. This is a scientific project without commercial interests, that is not in bookstores, but free in Internet. 2. Financial and legal claims against this project, will result in the contribution and the name of contributor in the next edition canceled. 3. This project has been sponsored by the Federal Republic of Germany, Department for Social Benefits, city of Neuss. 4. Correct spelling and orthography is subject of a constant fight between me and my computer – AND THE SOFTWARE in use – and normally the other side is the winning party! Editor`s note – Vorwort des Herausgebers preface 1 ENGLISH SHORT PREFACE „Paul Smith“ is a FAKE-IDENTY behind which very probably is a COLLCETIVE of writers and researchers, using a more RATIONAL and SOBER approach towards the complex of Rennes-le-Chateau and to related complex of „Priory of Sion“ (Prieure de Sion of Pierre Plantard, Geradrd de Sede, Phlippe de Cherisey, Jean-Luc Chaumeil and others). -

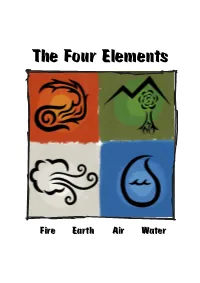

The Four Elements

The Four Elements Fire Earth Air Water Amanda Buys’ Spiritual Covering This is a product of Kanaan Ministries, a non-profit ministry under the covering of: • Roly, Amanda’s husband for more than thirty-five years. • River of Life Family Church Pastor Edward Gibbens Vanderbijlpark South Africa Tel: +27 (0) 16 982 3022 Fax: +27 (0) 16 982 2566 Email: [email protected] There is no copyright on this material. However, no part may be reproduced and/or presented for personal gain. All rights to this material are reserved to further the Kingdom of our Lord Jesus Christ ONLY. For further information or to place an order, please contact us at: P.O. Box 15253 27 John Vorster Avenue Panorama Plattekloof Ext. 1 7506 Panorama 7500 Cape Town Cape Town South Africa South Africa Tel: +27 (0) 21 930 7577 Fax: 086 681 9458 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.kanaanministries.org Office hours: Monday to Friday, 9 AM to 3 PM Kanaan International Website Website: www.eu.kanaanministries.org Kanaan Ministries: The Four Elements (10/2013) 2 Preface These prayers have been written according to personal opinions and convictions, which are gathered from many counseling sessions and our interpretation of the Word of GOD, the Bible. In no way have these prayers been written to discriminate against any persons, churches, organizations, and/or political parties. We ask therefore that you handle this book in the same manner. What does it mean to renounce something? To renounce means to speak of one’s self. If something has been renounced it has been rejected, cut off, or the individual is refusing to follow or obey. -

The Dimensions of Paradise: Sacred Geometry, Ancient Science, and The

The Dimensions of Paradise: Sacred Geometry, Ancient Science, and the Heavenly Order on Earth, 2008, 256 pages, John Michell, 159477773X, 9781594777738, Inner Traditions / Bear & Co, 2008 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1ytuLqO http://www.abebooks.com/servlet/SearchResults?sts=t&tn=The+Dimensions+of+Paradise%3A+Sacred+Geometry%2C+Ancient+Science%2C+and+the+Heavenly+Order+on+Earth&x=51&y=16 An in-depth look at the role of number as a bridge between Heaven and Earth • Reveals the numerical code by which the ancients maintained high standards of art and culture • Sets out the alchemical formulas for the fusion of elements and the numerical origins of various sacred names and numbers • Describes the rediscovery of knowledge associated with the Holy Grail, through which the influence of the Heavenly Order is made active on Earth The priests of ancient Egypt preserved a geometrical canon, a numerical code of harmonies and proportions, that they applied to music, art, statecraft, and all the institutions of their civilization. Plato, an initiate in the Egyptian mysteries, said it was the instrument by which the ancients maintained high, principled standards of civilization and culture over thousands of years. In The Dimensions of Paradise, John Michell describes the results of a lifetime’s research, demonstrating how the same numerical code underlies sacred structures from ancient times to the Christian era. In the measurements of Stonehenge, the foundation plan of Glastonbury, Plato’s ideal city, and the Heavenly City of the New Jerusalem described in the vision of Saint John lie the science and cosmology on which the ancient world order was founded. -

Newsletter 129 September 2018

Staffordshire Archaeological and Historical Society NEWSLETTER September 2018 Web: www.sahs.uk.net Issue No 129 email:[email protected] President: Dr John Hunt BA, PhD, FSA, FRHistS, PGCE. Tel: 01543423549 Hon. General Secretary: Vacant Hon. Treasurer: Mr K J Billington, ACIB. Tel: 01543 278989 Bradgate Park June 2018 Dr Richard Thomas of the University of Leicester showing members his current excavation in Dog Kennel Meadow on a sunny June evening at Bradgate. Page 1 of 18 Lecture Season 2018-2019 28th September 2018 Richard Bifield 1709-2009: Celebrating the 300th anniversary of the Birth of the Industrial Revolution at Coalbrookdale 1709 refers to the date when Abraham Darby first perfected the technique of smelting iron using coke from coal as opposed to charcoal the traditional fuel. From the innovation stemmed a whole series of technological firsts that made Coalbrookdale the world's most important iron making district by the end of the 18th century. Richard qualified as a Town Planner working at Lincoln, Newcastle upon Tyne, Reading and finally before retiring to the Wrekin as Conservation Officer. 12 October 2018 Nigel Page Recent Investigations at Baginton Warwickshire Nigel is a Senior Archaeological Officer at Archaeology Warwickshire and since joining AW in 2017 has worked on some incredible projects including a small Early Bronze Age hengiform monument that had five later Bronze Age burials in the ditch in Newbold on Stour. But, if that wasn’t enough for his first year he then moved onto this site at Baginton, which was not only one of the largest area excavations we have done, but it also turned out to be an incredibly important site. -

Open PDF 588KB

House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Formal Minutes Session 2017–19 The Home Affairs Committee The Home Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Home Office and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon Yvette Cooper MP (Chair, Labour, Normanton, Pontefract and Castleford) Rehman Chishti MP (Conservative, Gillingham and Rainham) Sir Christopher Chope MP (Conservative, Christchurch) Janet Daby MP (Labour, Lewisham East) Stephen Doughty MP (Labour (Co-op), Cardiff South and Penarth) Chris Green MP (Conservative, Bolton West) Kate Green MP (Labour, Stretford and Urmston) Tim Loughton MP (Conservative, East Worthing and Shoreham) Stuart C. McDonald MP (Scottish National Party, Cumbernauld, Kilsyth & Kirkintilloch East) Toby Perkins MP (Labour, Chesterfield) Douglas Ross MP (Conservative, Moray) The following Members were members of the Committee during the Session: Preet Kaur Gill MP (Labour (Co-op), Birmingham, Edgbaston) Sarah Jones MP (Labour, Croydon Central) Kirstene Hair MP (Conservative, Angus) Rt Hon Esther McVey MP (Conservative, Tatton) Alex Norris MP (Labour (Co-op), Nottingham North) Will Quince MP (Conservative, Colchester) Naz Shah MP (Labour, Bradford West) John Woodcock MP (Independent, Barrow and Furness) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/homeaffairscom.