Jeremy Montagu Did Shawms Exist in Antiquity? Page 1 of 4 1 but See

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

6. Theodor Rogalski, Conductor, Composer and Professor

DOI: 10.2478/rae-2021-0006 Review of Artistic Education no. 21 2021 35-45 6. THEODOR ROGALSKI, CONDUCTOR, COMPOSER AND PROFESSOR. 3 ROMANIAN DANCES, CONDUCTING STYLISTIC ANALYSIS 13 Iulian Rusu Abstract: Dancing in the culture of all peoples is a form of artistic manifestation with various functions, mystical, hunting warriors, etc., with deep roots in the very beginning of the first forms of organization of human communities. At national level, our people are the keeper of old and wonderful folk traditions, with dances of great wealth and variety. In our popular creation, the choreographic term “danse” is called “play”. Romanian dances have various ritual, ceremonial, or party functions, related to specific occasions. As a spatial deployment, they are divided into several categories: group, band, couple and soloistic. Theodor Rogalski in the Three Romanian dances highlights the beauty and vitality of the character of our people, especially through orchestration and the timbral coloring of the instruments. The conducting analysis of the 3 Romanian dances can also be a teaching material that is designed to guide the young musicians on the way to musical analysis. Key words: analysis, pedagogue, composer, dance, rhythmic plasticity 1. Introduction - Theodor Rogalski14 He was one of Alfonso Castaldi's disciples at the Bucharest Conservatory between 1919 and 1920, continued in Leipzig between 1920 and 1923, studying the conducting with Siegfried Karg-Elent and at Schola Cantorum from Paris 1924-1926, with Vincent d'Indy, Maurice Ravel. Returning home, he became a Cho repeater to the Romanian Opera in Bucharest between 1926-1930. In 1930, he conducted the Opera Boris Godunov by Modest Mussorgski with the famous Russian bass Teodor Saliapin, among the others. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2001, Tanglewood

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

Final Program for the ATS International Conference Is Available in Printed and Digital Format

WELCOME TO ATS 2017 • WASHINGTON, DC Welcome to ATS 2017 Welcome to Washington, DC for the 2017 American Thoracic Society International Conference. The conference, which is expected to draw more than 15,000 investigators, educators, and clinicians, is truly the destination for pediatric and adult pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine professionals at every level of their careers. The conference is all about learning, networking and connections. Because it engages attendees across many disciplines and continents, the ATS International Conference draws a large, diverse group of participants, a dedicated and collegial community that inspires each of us to make a difference in patients’ lives, now and in the future. By virtue of its size — ATS 2017 features approximately 6,700 original research projects and case reports, 500 sessions, and 800 speakers — participants can attend David Gozal, MD sessions and special events from early morning to the evening. At ATS 2017 there will be something for President everyone. American Thoracic Society Don’t miss the following important events: • Opening Ceremony featuring a keynote presentation by Nobel Laureate James Heckman, PhD, MA, from the Center for the Economics of Human Development at the University of Chicago. • Ninth Annual ATS Foundation Research Program Benefit honoring David M. Center, MD, with the Foundation’s Breathing for Life Award on Saturday. • ATS Diversity Forum will feature Eliseo J. Pérez-Stable, MD, Director, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities at the National Institutes of Health. • Keynote Series highlight state of the art lectures on selected topics in an unopposed format to showcase major discoveries in pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine. -

The Secret of the Bagpipes: Controlling the Bag. Techniques, Skill and Musicality

CASSANDRE BALOSSO-BARDIN,a AUGUSTIN ERNOULT,b PATRICIO DE LA CUADRA,c BENOÎT FABRE,b AND ILYA FRANCIOSIb The Secret of the Bagpipes: Controlling the Bag. Techniques, Skill and Musicality. hen interviewed about the technique as the Greek tsampouna or the Tunisian mizwid) to of the bag, bagpipe maker and award- a fully chromatic scale over two octaves (the uilleann winning Galician piper Cristobal Prieto pipes from Ireland and some Northumbrian small- Wsaid that. ‘the handling of the bag is one of the most pipes chanters). Bagpipes in their simplest form are important things. The secret of the bagpipes is how composed of a bag with a blowpipe and a melodic one uses the bag […] You need a lot of coordination: pipe (hereafter referred to as the chanter).2 Other blowing, fingers […] it depends on the arm, the pipes can then be added such as a second melodic pressure of the air. The [finger] technique is much pipe, semi-melodic pipes or drones.3 The blowpipe simpler. Everyone blows all over the place when they is usually, but not always, fitted with a small valve start to play. It’s like a car: you have to think how you in order to prevent the air from leaving the bag. In are going to do all of this at the same time. The use models without this system, the piper uses his/her of the bag is the most important aspect, even more tongue to prevent the air from escaping whilst s/he than the fingers, [or] velocity’.1 breathes in. -

Woodwind Family

Woodwind Family What makes an instrument part of the Woodwind Family? • Woodwind instruments are instruments that make sound by blowing air over: • open hole • internal hole • single reeds • double reed • free reeds Some woodwind instruments that have open and internal holes: • Bansuri • Daegeum • Fife • Flute • Hun • Koudi • Native American Flute • Ocarina • Panpipes • Piccolo • Recorder • Xun Some woodwind instruments that have: single reeds free reeds • Clarinet • Hornpipe • Accordion • Octavin • Pibgorn • Harmonica • Saxophone • Zhaleika • Khene • Sho Some woodwind instruments that have double reeds: • Bagpipes • Bassoon • Contrabassoon • Crumhorn • English Horn • Oboe • Piri • Rhaita • Sarrusaphone • Shawm • Taepyeongso • Tromboon • Zurla Assignment: Watch: Mr. Gendreau’s woodwind lesson How a flute is made How bagpipes are made How a bassoon reed is made *Find materials in your house that you (with your parent’s/guardian’s permission) can use to make a woodwind (i.e. water bottle, straw and cup of water, piece of paper, etc). *Find some other materials that you (with your parent’s/guardian’s permission) you can make a different woodwind instrument. *What can you do to change the sound of each? *How does the length of the straw effect the sound it makes? *How does the amount of water effect the sound? When you’re done, click here for your “ticket out the door”. Some optional videos for fun: • Young woman plays music from “Mario” on the Sho • Young boy on saxophone • 9 year old girl plays the flute. -

Glossary Ahengu Shkodran Urban Genre/Repertoire from Shkodër

GLOSSARY Ahengu shkodran Urban genre/repertoire from Shkodër, Albania Aksak ‘Limping’ asymmetrical rhythm (in Ottoman theory, specifically 2+2+2+3) Amanedes Greek-language ‘oriental’ urban genre/repertory Arabesk Turkish vocal genre with Arabic influences Ashiki songs Albanian songs of Ottoman provenance Baïdouska Dance and dance song from Thrace Čalgiya Urban ensemble/repertory from the eastern Balkans, especially Macedonia Cântarea României Romanian National Song Festival: ‘Singing for Romania’ Chalga Bulgarian ethno-pop genre Çifteli Plucked two-string instrument from Albania and Kosovo Čoček Dance and musical genre associated espe- cially with Balkan Roma Copla Sephardic popular song similar to, but not identical with, the Spanish genre of the same name Daouli Large double-headed drum Doina Romanian traditional genre, highly orna- mented and in free rhythm Dromos Greek term for mode/makam (literally, ‘road’) Duge pjesme ‘Long songs’ associated especially with South Slav traditional music Dvojka Serbian neo-folk genre Dvojnica Double flute found in the Balkans Echos A mode within the 8-mode system of Byzan- tine music theory Entekhno laïko tragoudhi Popular art song developed in Greece in the 1960s, combining popular musical idioms and sophisticated poetry Fanfara Brass ensemble from the Balkans Fasil Suite in Ottoman classical music Floyera Traditional shepherd’s flute Gaida Bagpipes from the Balkan region 670 glossary Ganga Type of traditional singing from the Dinaric Alps Gazel Traditional vocal genre from Turkey Gusle One-string, -

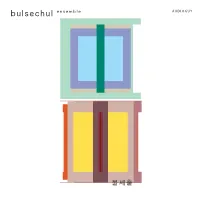

Bulsechul Ensemble

bulsechul ensemble 불세출 박계전 김용하 Park Gyejeon 배정찬 Kim Yonghwa 최덕렬 Bae Jungchan 이준 Choi Deokyol 박제헌 Lee Joon Park Jehun 김진욱 전우석 Kim Jinwook Jeon Wooseok [email protected] Facebook.com/bulsechul Youtube.com/bulsechul 풍류도시 연 북청 달빛 종로풍악 신천풍류 푸너리 지옥가 Flowing City Kite Bukcheong Moonlight Song of Jongno Sincheonpungryu Puneori Divine Song 6:03 4:24 8:10 6:57 8:07 8:20 6:11 7:32 • • • • • • • • 작곡 최덕렬 작곡 김용하 작곡 김용하 작곡 최덕렬 작곡 최덕렬 작곡 박계전 작곡 이준 작·편곡 불세출 Composed by Composed by Composed by Composed by Composed by Composed by Composed by Composed and Choi Deokyol Kim Yonghwa Kim Yonghwa Choi Deokyol Choi Deokyol Park Gyejeon Lee Joon Arranged by Bulsechul 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 이준 가야금, 꽹과리 가야금 가야금 가야금 가야금 가야금, 꽹과리 Lee Joon Gayageum, Kkwaenggwari Gayageum Gayageum Gayageum Gayageum Gayageum, Kkwaenggwari 전우석 거문고, 바라 거문고 거문고 거문고 거문고 거문고 거문고, 바라 Jeon Wooseok Geomungo, Bara Geomungo Geomungo Geomungo Geomungo Geomungo Geomungo, Bara 김진욱 대금, 단소, 퉁소, 징 대금 대금, 단소 대금 대금, 퉁소 대금, 징 Kim Jinwook Daegeum, Danso, Tungso, Jing Daegeum Daegeum, Danso Daegeum Daegeum, Tungso Daegeum, Jing 박제헌 아쟁, 양금, 바라 아쟁 아쟁, 양금 아쟁 아쟁, 바라 Park Jehun Ajaeng, Yanggeum, Bara Ajaeng Ajaeng, Yanggeum Ajaeng Ajaeng, Bara 배정찬 장구, 소리 장구 장구 장구 장구, 소리 Bae Jungchan Janggu, Vocal Janggu Janggu Janggu Janggu, Vocal 박계전 피리, 생황, 태평소 피리, 태평소 생황 피리 피리, 생황 피리, 태평소, 생황 Park Gyejeon Piri, Saenghwang, Taepyeongso Piri, Taepyeongso Saenghwang Piri Piri, Saenghwang Piri, Taepyeongso, Saenghwang 해금, 꽹과리 해금 해금 해금 해금 해금, 꽹과리 Kim Yonghwa Haegeum, Kkwaenggwari Haegeum Haegeum Haegeum Haegeum Haegeum, Kkwaenggwari 최덕렬 기타, 징, 정주 기타 기타 기타 기타 기타 징, 정주 징 Choi Deokyol Acoustic Guitar, Jing, Jeongju Acoustic Guitar Acoustic Guitar Acoustic Guitar Acoustic Guitar Acoustic Guitar Jing, Jeongju Jing 지옥가 Divine Song 낮고 느리다. -

Heckelphone / Bass Oboe Repertoire

Heckelphone / Bass Oboe Repertoire by Peter Hurd; reorganized and amended by Holger Hoos, editor-in-chief since 2020 version 1.2 (21 March 2021) This collection is based on the catalogue of musical works requiring heckelphone or bass oboe instrumen- tation assembled by Peter Hurd beginning in 1998. For this new edition, the original version of the repertoire list has been edited for accuracy, completeness and consistency, and it has been extended with a number of newly discovered pieces. Some entries could not (yet) be rigorously verified for accuracy; these were included nonetheless, to provide leads for future investigation, but are marked clearly. Pieces were selected for inclusion based solely on the use of heckelphone, bass oboe or lupophone, without any attempt at assessing their artistic merit. Arrangements of pieces not originally intended for these instruments were included when there was clear evidence that they had found a significant audience. The authors gratefully acknowledge contributions by Michael Finkelman, Alain Girard, Thomas Hiniker, Robert Howe, Gunther Joppig, Georg Otto Klapproth, Mark Perchanok, Andrew Shreeves and Michael Sluman. A · B · C · D · E · F · G · H · I · J · K · L · M · N · O · P · Q · R · S · T · U · V · W · X · Y · Z To suggest additions or corrections to the repertoire list, please contact the authors at [email protected]. All rights reserved by Peter Hurd and Holger H. Hoos, 2021. A Adès, Thomas (born 1971, UK): Asyla, op. 17, 1997 Duration: 22-25min Publisher: Faber Music (057151863X) Remarks: for large orchestra; commissioned by the John Feeney Charitable Trust for the CBSO; first performed on 1997/10/01 in the Symphony Hall, Birmingham, UK by the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra under Simon Rattle Tags: bass oboe; orchestra For a link to additional information about the piece, the composer and to a recording, please see the on-line version of this document at http://repertoire.heckelphone.org. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 29,1909-1910, Trip

CONVENTION HALL . BUFFALO Twenty-ninth Season, J909-19J0 MAX FIEDLER, Conductor Programme WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE MONDAY EVENING, JANUARY 31 AT 8.15 PRECISELY COPYRIGHT, 1909, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER >^v Sent Free upon A Little Hand-Book Request For all Music Lovers Here is a little book with a big thought back of it. Henry T. Finck, the noted author and musi- cal critic, has done for music what President Eliot did for literature in his much discussed " five foot library." Taking the great PIANOLA catalog of over 15,000 titles, Mr. Finck has selected 130 choice pieces that he specially recommends. Moreover, he has grouped them into " Twenty Musical Evenings," so that they represent a fascinating plan for home entertainment. Each program is followed by interesting comments. The book is a sort of Pianolist's " Baedeker," guiding the novice in the selection of music which is both first-class and popular. The PIANOLA PIANO Opens Up a Wonderful Field of Home Entertainment Anyone who reads this little book can- is the only one that the great pianists not fail to be impressed with the un- themselves are willing to endorse. limited enjoyment that the PIANOLA Only in the PIANOLA and PIAN- Piano brings into the home. Here is a OLA Piano are to be found the vital delightful means of entertainment in improvements that give the human- which the entire family shares. like quality to the playing. The PIANOLA Piano is the stan- The Metrostyle and Themodist are dard instrument of its kind. -

Download (12MB)

10.18132/LFZE.2012.21 Liszt Ferenc Zeneművészeti Egyetem 28. számú művészet- és művelődéstörténeti tudományok besorolású doktori iskola KELET-ÁZSIAI DUPLANÁDAS HANGSZEREK ÉS A HICHIRIKI HASZNÁLATA A 20. SZÁZADI ÉS A KORTÁRS ZENÉBEN SALVI NÓRA TÉMAVEZETŐ: JENEY ZOLTÁN DLA DOKTORI ÉRTEKEZÉS 2011 10.18132/LFZE.2012.21 SALVI NÓRA KELET-ÁZSIAI DUPLANÁDAS HANGSZEREK ÉS A HICHIRIKI HASZNÁLATA A 20. SZÁZADI ÉS A KORTÁRS ZENÉBEN DLA DOKTORI ÉRTEKEZÉS 2011 Absztrakt A disszertáció megírásában a fő motiváció a hiánypótlás volt, hiszen a kelet-ázsiai régió duplanádas hangszereiről nincs átfogó, ismeretterjesztő tudományos munka sem magyarul, sem más nyelveken. A hozzáférhető irodalom a teljes témának csak egyes részeit öleli fel és többnyire valamelyik kelet-ázsiai nyelven íródott. A disszertáció második felében a hichiriki (japán duplanádas hangszer) és a kortárs zene viszonya kerül bemutatásra, mely szintén aktuális és eleddig fel nem dolgozott téma. A hichiriki olyan hangszer, mely nagyjából eredeti formájában maradt fenn a 7. századtól napjainkig. A hagyomány előírja, hogy a viszonylag szűk repertoárt pontosan milyen módon kell előadni, és ez az előadásmód több száz éve gyakorlatilag változatlannak tekinthető. Felmerül a kérdés, hogy egy ilyen hangszer képes-e a megújulásra, integrálható-e a 20. századi és a kortárs zenébe. A dolgozat első részében a hozzáférhető szakirodalom segítségével a szerző áttekintést nyújt a duplanádas hangszerekről, bemutatja a két alapvető duplanádas hangszertípust, a hengeres és kúpos furatú duplanádas hangszereket, majd részletesen ismerteti a kelet-ázsiai régió duplanádas hangszereit és kitér a hangszerek akusztikus tulajdonságaira is. A dolgozat második részéhez a szerző összegyűjtötte a fellelhető, hichiriki-re íródott 20. századi és kortárs darabok kottáit és hangfelvételeit, és ezek elemzésével mutat rá a hangszerjáték új vonásaira. -

Quantum Leap RA Virtual Instrument Manual

Quantum Leap RA Virtual Instrument Users’ Manual QUANTUM LEAP RA VIRTUAL INSTRUMENT The information in this document is subject to change without notice and does not rep- resent a commitment on the part of East West Sounds, Inc. The software and sounds described in this document are subject to License Agreements and may not be copied to other media. No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced or otherwise transmitted or recorded, for any purpose, without prior written permission by East West Sounds, Inc. All product and company names are ™ or ® trademarks of their respective owners. © East West Sounds, Inc., 2008–2011. All rights reserved. East West Sounds, Inc. 6000 Sunset Blvd. Hollywood, CA 90028 USA 1-323-957-6969 voice 1-323-957-6966 fax For questions about licensing of products: [email protected] For more general information about products: [email protected] http://support.soundsonline.com Version of February 2011 ii QUANTUM LEAP RA VIRTUAL INSTRUMENT 1. Welcome 2 About EastWest 3 Producer: Nick Phoenix 4 Credits 5 How to Use This and the Other Manuals 5 Using the Adobe Acrobat Features 5 The Master Navigation Document 6 Online Documentation and Other Resources Click on this text to open the Master Navigation Document 1 QUANTUM LEAP RA VIRTUAL INSTRUMENT Welcome About EastWest EastWest (www.soundsonline.com) has been dedicated to perpetual innovation and un- compromising quality, setting the industry standard as the most critically acclaimed producer of Sample CDs and Virtual (software) Instruments. Founder and producer Doug Rogers has over 30 years experience in the audio industry and is the recipient of many recording industry awards including “Recording Engineer of the Year.” In 2005, “The Art of Digital Music” named him one of “56 Visionary Artists & Insiders” in the book of the same name.