'Everything Is Community': Developer and Incoming Resident Experiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMPASS Research Centre Barry Milne and Nichola Shackleton

New New Zealand Data Quality of the 2018 New Zealand Census Barry Milne COMPASS Seminar Tuesday, 3 March 2020 The University of Auckland The University of Outline Background to the Census What happened with Census 2018? Why did it happen? What fixes were undertaken? What are the data quality implications? New New Zealand 1. Population counts 2. Electoral implications 3. Use of alternative data sources 4. Poor/very poor quality variables Guidelines for users of the Census The University of Auckland The University of Some recommendations that (I think) should be taken on board 2 Background New Zealand Census of Population and Dwellings Official count of how many people and dwellings there are in the country at a set point in time (by age, sex, ethnicity, region, community) Detailed social, cultural and socio-economic information about the total New Zealand population and key groups in the population Undertaken since 1851, and every five years since 1881, with exceptions New New Zealand • No census during the Great Depression (1931) • No census during the Second World War (1941) • The 1946 Census was brought forward to September 1945 • The Christchurch earthquakes caused the 2011 Census to be re-run in 2013 Since 1966, held on first Tuesday in March of Census year The most recent census was undertaken on March 6, 2018 The University of Auckland The University of http://archive.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/info-about-the-census/intro-to-nz-census/history/history-summary.aspx 3 Background Census is important for Electorates and electoral boundaries Central and local government policy making and monitoring Allocating resources from central government to local areas Academic and market research Statistical benchmarks New New Zealand A data frame to select samples for social surveys Many other things beside… “every dollar invested in the census generates a net benefit of five dollars in the economy” (Bakker, 2014, Valuing the census, p. -

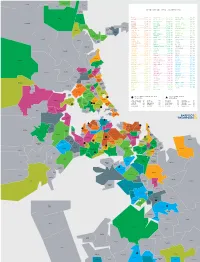

TOP MEDIAN SALE PRICE (OCT19—SEP20) Hatfields Beach

Warkworth Makarau Waiwera Puhoi TOP MEDIAN SALE PRICE (OCT19—SEP20) Hatfields Beach Wainui EPSOM .............. $1,791,000 HILLSBOROUGH ....... $1,100,000 WATTLE DOWNS ......... $856,750 Orewa PONSONBY ........... $1,775,000 ONE TREE HILL ...... $1,100,000 WARKWORTH ............ $852,500 REMUERA ............ $1,730,000 BLOCKHOUSE BAY ..... $1,097,250 BAYVIEW .............. $850,000 Kaukapakapa GLENDOWIE .......... $1,700,000 GLEN INNES ......... $1,082,500 TE ATATŪ SOUTH ....... $850,000 WESTMERE ........... $1,700,000 EAST TĀMAKI ........ $1,080,000 UNSWORTH HEIGHTS ..... $850,000 Red Beach Army Bay PINEHILL ........... $1,694,000 LYNFIELD ........... $1,050,000 TITIRANGI ............ $843,000 KOHIMARAMA ......... $1,645,500 OREWA .............. $1,050,000 MOUNT WELLINGTON ..... $830,000 Tindalls Silverdale Beach SAINT HELIERS ...... $1,640,000 BIRKENHEAD ......... $1,045,500 HENDERSON ............ $828,000 Gulf Harbour DEVONPORT .......... $1,575,000 WAINUI ............. $1,030,000 BIRKDALE ............. $823,694 Matakatia GREY LYNN .......... $1,492,000 MOUNT ROSKILL ...... $1,015,000 STANMORE BAY ......... $817,500 Stanmore Bay MISSION BAY ........ $1,455,000 PAKURANGA .......... $1,010,000 PAPATOETOE ........... $815,000 Manly SCHNAPPER ROCK ..... $1,453,100 TORBAY ............. $1,001,000 MASSEY ............... $795,000 Waitoki Wade HAURAKI ............ $1,450,000 BOTANY DOWNS ....... $1,000,000 CONIFER GROVE ........ $783,500 Stillwater Heads Arkles MAIRANGI BAY ....... $1,450,000 KARAKA ............. $1,000,000 ALBANY ............... $782,000 Bay POINT CHEVALIER .... $1,450,000 OTEHA .............. $1,000,000 GLENDENE ............. $780,000 GREENLANE .......... $1,429,000 ONEHUNGA ............. $999,000 NEW LYNN ............. $780,000 Okura Bush GREENHITHE ......... $1,425,000 PAKURANGA HEIGHTS .... $985,350 TAKANINI ............. $780,000 SANDRINGHAM ........ $1,385,000 HELENSVILLE .......... $985,000 GULF HARBOUR ......... $778,000 TAKAPUNA ........... $1,356,000 SUNNYNOOK ............ $978,000 MĀNGERE ............. -

Attachment Manurewa Open Space Netw

Manurewa Open Space Network Plan August 2018 1 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Purpose of the network plan ................................................................................................................................ 7 1.2 Strategic context .................................................................................................................................................. 7 1.3 Manurewa Local Board area ............................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Current State ..................................................................................................................................................... 12 Treasure ............................................................................................................................................................. 12 Enjoy ................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Connect .............................................................................................................................................................. 22 -

Routes Manurewa Fare Zones & Boundaries Routes

Manurewa Routes Fare Zones 33 Papakura, Great South Rd, Manurewa, Manukau, Southern Bus Timetable Otahuhu Town Centre, Otahuhu Station & Boundaries 361 Manurewa, Clendon Park, Homai, Manukau, Tui Rd, Otara MIT North Campus Wellsford 362 Weymouth, Manurewa, Great South Rd, Manukau Station Omaha 363 Manurewa, Wattle Downs Matakana 365 Manukau Station, Homai, Manurewa, Randwick Park, Warkworth Takanini Station, Porchester Rd, Papakura Station 366 Manurewa, The Gardens, Everglade Dr, Manukau Station Warkworth Waiwera Helensville Hibiscus Coast Your guide to buses in this area Other timetables available in this area that may interest you Orewa Wainui Kaukapakapa Hibiscus Coast Gulf Harbour Timetable Routes Waitoki Mangere, Otahuhu, 31, 32, 309, 309X, 313, 321, 324, Upper North Shore Papatoetoe 25, 326, 380 Otara, Papatoetoe, Albany 31, 33, 314, 325, 351, 352, 353, 361 Waiheke Highbrook, East Tamaki Constellation Lower North Shore Riverhead Hauraki Gulf Takapuna Rangitoto Papakura 33, 365, 371, 372, 373, 376, 377, 378 Island 33 Huapai Westgate City Pukekohe, Waiuku Isthmus 391, 392, 393, 394, 395, 396, 398, 399 Waitemata Harbour Britomart Swanson Airporter 380 Kingsland Newmarket Beachlands Henderson Southern Line Train timetable Waitakere Panmure Eastern Line New Lynn Waitakere Onehunga 361 362 363 Ranges Otahuhu Botany Manukau Manukau Airport Manukau Harbour North Manukau South 365 366 Papakura Franklin Pukekohe Port Waikato Waiuku Tuakau Warkworth Huapai Manukau North Hibiscus Coast Waitakere Manukau South Upper North Shore City Franklin -

Manurewa Local Board Meeting Held on 5/12/2019

Work Programme 2019/2020 Q1 Report ID Activity Name Activity Description Lead Dept / Budget Budget Activity RAG Q1 Commentary Unit or CCO Source Status Arts, Community and Events 110 Manurewa Lifelong Enable Manurewa's growing number of residents aged 55 years and over CS: ACE: LDI: Opex $65,000 In progress Green The Manurewa Seniors Network meetings are on hold as the meetings have been Learning and Seniors to engage in community activities and access the Life Long Learning Community service provider-led rather than community-led by seniors, and have not been well Network Scholarship to apply for funds for lifelong learning opportunities. Empowerment attended. Strengthen the capacity and partnerships of the Manurewa Seniors Haumaru Housing was unable to meet all its deliverables and have returned their Network to deliver Manurewa Seniors Network Expo and Life Long unspent funding. Staff are engaging a local contractor to identify existing local Learning Fund for seniors in Manurewa. ($15k) seniors networks and groups, and isolated seniors in the local board area, to establish their needs, strengths and aspirations. Results of the project will be Fund Manurewa Business Association to deliver Shuttle Loop Service. available in Q2. ($50k) 111 Manurewa Youth Fund the Youth Council to be involved in building the capacity of young CS: ACE: LDI: Opex $72,000 In progress Green The Manurewa Rangatahi scholarship round will be open for interested applicants Council and Rangatahi people to shape plans, neighbourhood facilities, and encourage and Community by the end of Q1. The 2019/2020 application and criteria have been updated and Scholarships support youth-led activities, linking into placemaking activity in Manurewa. -

Part 3 New and Future Urban Expansion

PART 3 - CONTENTS PART 3 NEW AND FUTURE URBAN EXPANSION 3 .1 INTRODUCTION 3.1 .1 General 3.1 .2 Urban Development Strategy 3.1.3 New Urban Zoning 3. 1 .4 Future Development Zoning and Staging 3 . 1 . 5 Structure Plans 3.2 NEW DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVE AND POLICIES 3.3 CLENDON PARK 3.4 FLAT BUSH 3.5 BOTANY ROAD WEST 3 .6 HILL ROAD 3 .7 WOODSIDE HEIGHTS 3 .8 MANGEMANGEROA 3 .9 TE U KAIPO 3 .10 WESTNEY ROAD 3.11 MASSEY ROAD 3.12 ORUARANGI SOUTH CITY OF MANUKAU SECOND REVIEW PART 3 - NEW AND FUTURE URBAN EXPANSION 3.1 INTRODUCTION ( 3.1.1 General This part of the Scheme sets out the objectives and policies for the expansion of the City's urban area for the purpose of establishing the ultimate form of the City. An indication is given of the pattern and sequence in which development will occur and the means by which the releasing of land from rural to urban purposes will be implemented. Also included in this Part are structure plans for: Clendon Park Flat Bush Botany Road West Hill Road Woodside Heights Mangemangeroa Te U Kaipo Westney Road Massey Road Oruarangi South 3.1.2 Urban Development Strategy 3.1.2.1 Plan 3A gives an overview of Council's urban development strategy. The primary aim of the Council's future development policies is to achieve by way of controlled development the consolidation of the City in order to improve transport linkages and create a better relationship between home, work, shopping and recreational facilities. -

Part 2 the City: Present and Future Trends

• PART 2 - CONTENTS PART 2 THE CITY: PRESENT AND FUTURE TRENDS 2. 1 THE FORM OF THE CITY 2.2 GROWTH OF THE CITY 2.3 ETHNIC ORIGIN OF POPULATION 2.4 EMPLOYMENT 2.5 BUILDING DEVELOPMENT AND DEMAND 2.6 TRANSPORTATION AND LAND USE 2.7 FUTURE URBAN GROWTH 2.8 LAND PRESENTLY ZONED FOR URBAN USES 2.9 RURAL LAND USE 2.10 CONTEXT OF THE PLANNING SCHEME CITY OF MANUKAU SECOND REVIEW PART 2 - THE CITY: PRESENT AND FUTURE TRENDS 2.1 THE FORM OF THE CITY Manukau City had a population in March 1986 of 177,248. Its land area of over 600 square kilometres dominates the southern part of the Auckland Region. The territorial integrity of the district, stretches from the edge of the Auckland isthmus in the north to the Hunua Ranges in the south. The Manukau City Centre, 25 km south of Auckland Centre, is the natural geographical focus of the city's urban area. When fully developed the urban area will stretch out from the Centre southwards to Manurewa, northeastwards to Otara and Pakuranga and northwest to Mangere. Two-thirds of the City's land area is in rural use, ranging from dairy and town milk supply units to pastoral farming, horticulture and forestry. A distinctive feature of the district is its extensive coastline of 320 km. In the west is the Manukau Harbour, from which the City takes its name. In the east is the Hauraki Gulf and in the north the Tamaki River. Residential development in the urban part of the City has taken full advantage of the coastline. -

Chapter 6 — Heritage Page 1

Chapter 6 — Heritage Page 1 Chapter 6 — Heritage CONTENTS This chapter is presented as follows: 6.1 Introduction This outlines how heritage is defined and the statutory context of this chapter. 6.2 Resource Management Issues This outlines the significant resource management issues relating to heritage resources within the City. 6.3 Objectives This sets out the overall desired environmental outcomes for the heritage resources of the City. 6.4 Policies This describes how Council intends to ensure that the objectives for the City’s heritage resources are met. An explanation of the policies is given. A summary of the range of methods that are used to implement each policy is also included. 6.5 Heritage Strategy The strategy summarises the overall approach to managing the City’s natural and cultural heritage resources. 6.6 Implementation This broadly describes the regulatory and non-regulatory methods used to implement the policies for the management of the City’s heritage resources. 6.7 Anticipated Environmental Results This outlines the environmental outcomes anticipated from the implementation of the policies and methods as set out in the Heritage Chapter. 6.8 Procedures for Monitoring This outlines how Council will monitor the effectiveness of the Heritage provisions. Manukau Operative District Plan 2002 Chapter 6 — Heritage Page 2 6.9 Rules — Activities This sets out in an Activity Table the permitted and discretionary activities for the scheduled heritage resources of the City. 6.10 Rules – Matters for Control: Controlled Activities 6.11 -

New Zealand Gazette

.. No. 99 3093 SUPPLEMENT TO THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE OF THURSDAY, 9 NOVEMBER 1978 Published by Authority WELLINGTON: FRIDAY, 10 NOVEMBER 1978 GENERAL ELECTION 1978 Appointment of Returning Officers, and Polling Places . 10 NOVEMBER THE NEW ZEALAND GAZE11'E 3095 Returning Officers Appointed Murray Roy Hughes Wanganui. Kerry Anne Popplewell Wellington Central. Robert Kelvin Gay West Coast. IT is hereby notified that each of the under-mentioned persons John Henry Blackaby Western Hutt. has been appointed Returning Officer for the electoral district, Thomas Patrick Evans Whangarei. William Willcox ...... .. ... YaldhutSt. the name of which appears opposite his or her name: Clive Carlton Doughty ..... Eastern Maori. Emmett Sylvester Hawley ...... Albany. James Duncan McMillan .... .. Northern Maori. Kevin Patrick Nally Ashburton. Kurt Frederic Nelson Meyer Southern Maori. Mervyn Iva Hannan Auckland Central. Kevin John Gunn ...... Western Maori. James Walter Phillips Avon. Wellington, 9 November 1978. Robert John Mexted Awarua. Peter Weightman...... Bay of Islands. D .. S. Thomson, Minister of Justice. Riobard Norman Hall Birkenhead. Murray John Walfrey Christchurch Central. Gerald Wallace Sides Clutha. James Bertrand Kinney Curran Dunedin Central. Marcus Jones Dunedin North. Dorothy Gwendoline Guy ...... East Cape. Graham Martin Ford East Coast Bays. Kemara Pirimona Tukukino Eastern Hutt. Allan Newell David Dixon Eden. Polling Places Under the Electoral Act 1956 Appointed Rex Vincent ...... Fendalton. Anthony William White ...... Gisborne. Bryan John Bayley ...... Hamilton East. Joseph Matthew Glamuzina Hamilton West. KEITH HOLYOAKE, Governor-General Donald Roy Parkin Hastings. Alan John McKenzie Hauraki. PURSUANT to the Electoral Act 1956, I, Sir Keith Jacka Evan Christopher John Gould Hawkes Bay. Hol)'.oake, fthe. 9overno~-General of New Zealand, hereby Leonard John McKeown ..... -

Local Board Information and Agreements Draft Long-Term Plan 2012-2022

DRAFT LONG-TERM PLAN 2012-2022_ VOLUME FOUR LOCAL BOARD INFORMATION AND AGREEMENTS DRAFT LONG-TERM PLAN 2012-2022_ VOLUME FOUR LOCAL BOARD INFORMATION AND AGREEMENTS About this volume About this volume This is Volume Four of the four volumes that make up the draft LTP. It is set out in two parts, one which provides background on the role of local boards, their decision-making responsibilities and some general information about local board plans and physical boundaries. The second part contains the individual local board agreements for all 21 local boards, which contain detailed information about local activities, services, projects and programmes and the corresponding budgets for the period 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2013. Here we have also included additional information like ten-year budgets for each board and a capital projects list. What this volume covers: the status of draft local board agreements how to have your say during the public consultation period an overview of the local boards local board activities information on the development of local board plans and agreements local board financial information including a consolidated statement of expenditure on local activities about each local board, with an overview of the local board including their strategic priorities and a message from the chairperson draft local board agreements for each local board covering scope of activities levels of service and performance measures local activities including key initiatives and projects expenditure and funding notes to the local board agreements contact details, how to contact your local board, including individual contact details for each local board member an appendix to each Local Board information section which includes their expenditure statements and capital projects for the ten-year period 2012 to 2022. -

Crashes Roads

W What is planned? Proposed road safety improvements What are we seeking feedback on? We want your feedback to help us improve our plan for the proposed road safety improvements. Local until Friday 26 April 26 Friday until Auckland Transport (AT) are planning to make road safety improvements on residential Our transportation engineers have selected the type and location of each proposed safety knowledge will help give us a better understanding Public feedback is open is feedback Public streets in Manurewa to provide a safer environment for all road users. measure based on a variety of criteria. of the area, your needs, and any improvements that can be made to the design. We aim to reduce vehicle speeds by installing a Manurewa has been prioritised as an area for These include: combination of speed-calming measures such as You can help by telling us whether you improvement based on a number of factors, including: • Proximity to schools or other locations where there are a higher number of people speed humps, raised tables, and zebra crossings walking or on bikes. • Have any thoughts on the proposed safety where justified. The improvements are proposed Safety concerns raised by residents improvements. for within the area contained by Brown Road, • International best practice guidelines for positioning measures to reduce speed • Have any suggested changes to the proposed Roscommon Road, Russell Road and Weymouth in residential areas. Local Crash Analysis System (CAS) data road safety measures. Road, as shown on the enclosed map. – 213 accidents in the last five years • Space available between driveways and/or bus stops. -

South Au Pukekohe Waiuku

Ave od wo July 2018 July n Ro Where to catch your bus in the city Where to connect to other services How to Captain Princes Queens Marsden Cook Wharf Wharf Wharf Botany Town Centre Manukau Station Wharf ay W Manukau am get started h Bus Stop 6233 ers Centre Am t t B S S r PIER y e e l 31 Otara, Hunters Corner, Papatoetoe, n PIER 1 m i T PIER PIER 2 m u Davies Ave towards Papakura Manukau Bus Station l Mangere Town Centre Use the map on the other side to Ferry 4 3 P B Building 72C Chapel Rd, Cook Street, Howick, Quay St 33 Great South Rd, Manurewa 35 Chapel Rd, Ormiston, Botany Wynyard Quay St Pakuranga Rd, Panmure Quarter Interchange, Papakura Station Papatoetoe, Mangere Town Centre, 313 t identify which route(s) will get you to t Quay St M Social Britomart S Millhouse Dr, Meadowland Dr, t 72M S S Viaduct PWC e Tyler St Browns Rd, Clendon Park, Mahia Rd, Mangere Bridge, Onehunga 361 a c r r a T Pakuranga Rd, Panmure Harbour o e o p u w Manurewa Interchange a m Chapel Downs, Bairds Rd, Otara, T 325 h n i r Downtown m hu C C 72X Howick, Pakuranga, Panmure, g o hu e your destination. This map covers the Carpark AMP Galway St Ma Te Irirangi Dr n Otahuhu Station, Mangere Town Centre C n Spark Arena t Southern Mwy, Britomart Viaduct a re T D 352 East Tamaki, Highbrook, Panmure Basin Customs St W Customs St E r 733 Aviemore Dr, Highland Park, C H o 353 Preston Rd, Harris Rd, Botany m t a t Bucklands Beach Southern Suburbs – other AT guides for S S l l e m s e P w r e a e Q Ormiston, Mission Heights, Middlefi eld t h 355 o Botany Rd, Highland