Chapter 4 Simulations in the Los Angeles Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of Geotechnical Investigation Proposed Improvements

REPORT OF GEOTECHNICAL INVESTIGATION PROPOSED IMPROVEMENTS PROPOSED RIO HONDO SATELLITE CAMPUS EL RANCHO ADULT SCHOOL 9515 HANEY STREET PICO RIVERA, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: RIO HONDO PROGRAM MANAGEMENT TEAM Whittier, California January 20, 2016 Project 4953-15-0302 January 20, 2016 Mr Luis Rojas Rio Hondo Program Management Team c/o Rio Hondo College 3600 Workman Mill Road Whittier, California 90601-1699 Subject: LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Report of Geotechnical Investigation Proposed Improvements Proposed Rio Hondo Satellite Campus El Rancho Adult School 9515 Haney Street Pico Rivera, California, 90660 Amec Foster Wheeler Project 4953-15-0302 Dear Mr. Rojas: We are pleased to submit the results of our geotechnical investigation for the proposed improvements as part of the proposed Rio Hondo Satellite Campus at the El Rancho Adult School in Pico Rivera, California. This investigation was performed in general accordance with our proposal dated November 24, 2015, which was authorized by e-mail on December 15, 2015. The scope of our services was planned with Mr. Manuel Jaramillo of DelTerra. We have been furnished with a site plan and a general description of the proposed improvements. The results of our investigation and design recommendations are presented in this report. Please note that you or your representative should submit copies of this report to the appropriate governmental agencies for their review and approval prior to obtaining a permit. Correspondence: Amec Foster Wheeler 6001 Rickenbacker Road Los Angeles, California 90040 USA -

An Elusive Blind-Thrust Fault Beneath Metropolitan Los Angeles

R EPORTS 5 The intercept of the line with the abscissa yields Di/D 1/4, which is an extreme case, differs only by 36. N. A. Sulpice and R. J. D’Arcy, J. Phys. E 3, 477 (1970). 7% as compared with D 5 0. DV. This geometry-independent constant is i 37. Electrical charging due to the electron beam cannot 31. Microscopy was performed with a Philips CM30 200- account for the effect, because the charge found to characteristic for the specific nanotube under kV high-resolution TEM. reside on the nanotubes is positive rather than neg- investigation and is typically on the order of 32. The ripple mode may be a precursor to buckling, but ative. Furthermore, the amplitude of vibration at several volts. Similarly, attaching nanoscopic it should not be confused with bucking. Buckling (in resonance does not change with electron dose, as it contrast to rippling) is characterized as an instability would if electron beam charging were important. conducting particles to the nanotubes facilitates giving rise to a nonlinear response. It occurs in highly 38. M. Gurgoze, J. Sound Vib. 190, 149 (1996). measurements of their work functions. stressed nanotubes (and beams) and manifests as 39. We thank U. Landman, R. L. Whetten, L. Forro, and A. The methods developed here are also well one or several kinks with very small radii of curvature Zangwill for fruitful discussion and R. Nitsche for his suited to measure masses in the picogram-to- (about 1 to 10 nm). It is accompanied by abrupt analysis of the static bent nanotube. -

The L.A. Earthquake Sourcebook

THE L.A. EARTHQUAKE SOURCEBOOK Produced by Richard Koshalek and Mariana Amatullo 2/3 Copyright © 2008 Designmatters at Southern California earthquake maps reprinted Art Center College of Design. courtesy of the U. S. Geological Survey. Excerpt from All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-9618705-0-8 “Los Angeles Days” reprinted with the permission of Simon and Schuster Adult Publishing Group from Design: Sagmeister Inc., NYC After Henry by Joan Didion. Copyright © 1992 by Managing Editor: Gloria Gerace Joan Didion. All rights reserved. Pp. 97–100 from Ask Editor: Alex Carswell The Dust by John Fante. Copyright © 1980 by John Printer: Capital Offset Co. Fante. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers. Excerpt from As I Remember by Arnold Genthe. Copyright © 1936 by Reynal & Hitchcock. Reprinted by permission of Ayer Company Publishers. “When Mother Nature Visits Southern California” by David Hernandez, 1998, used by permission of the author. Excerpt from “Assembling California” from Annals of the Former World by John McPhee. Copyright © 1998 by John McPhee. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Excerpt from “Folklore of Earthquakes” from Fool’s Paradise: The Carey McWilliams Reader. Reprinted by permission of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated. Copyright © 1933 by Carey McWilliams. First published in American Mercury. “When Living on the Edge Becomes Stark–Naked Reality” originally appeared in the Los Angeles Times. Copyright © 1987 Carolyn See. Used by permission of the author. Excerpt from “The L.A. Quake” © 1994 Lawrence S C C Weschler. Used by permission of the author. The full E essay appeared in the Threepenny Review and is part an NSF+USGS center of Vermeer in Bosnia: Cultural Comedies and Political Tragedies, Pantheon, 2004. -

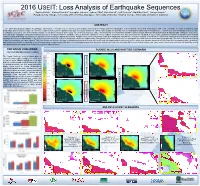

Abstract the Hazus Challenge

2016 USEIT: Loss Analysis of Earthquake Sequences Sophia Belvoir1, Vianca Severino2, Jenepher Zamora1, Jadson Silva4, Luis Gomez5, Jozi Pearson6, Mark Benthien6, Thomas Jordan6 1Pasadena City College, 2University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez, 4University of Brazilia, 5Chaffey College, 6University of Southern California ABSTRACT The 2016 Undergraduate Studies in Earthquake Information Technology (USE-IT) intern research program challenged the Hazard and Risk Visualization Team to illustrate threatening and probable multi-event earthquake scenarios in California using ShakeMaps and risk analysis maps. The interns are implementing FEMA’s Hazards United States (HAZUS) software to estimate and visualize the potential losses including physical damage of infrastructure, economic loss, and social impacts of these mul- ti-earthquake sequences. This is the first time multiple events will be analyzed with HAZUS. As a team based project, USEIT interns depend on collaboration with other working groups within the intern program to identify potential earthquake sequences. The Rate-State earthQuake Simulator (RSQSim) was run on a high performance computer (HPC) to generate catalogs of events. Rupture sequences were then selected to be visualized in SCEC-VDO. Earthquake sequences that were seen as most threatening had ShakeMap files created utilizing seismic hazard analysis (OpenSHA) software. Multiple events were combined as single ShakeMaps and imported into HAZUS for analysis. Ground motion values were combined and calculated in two differ- ent ways for multi-event ShakeMaps: 1) by using the greatest value and 2) sum of the squares, where the maps overlap. The greatest value method proves more appropriate for events that are further apart geographically. The sum of the squares method is ideal for events that are closer together. -

Tectonic Geomorphology of the Santa Ana Mountains

Final Technical Report ACTIVE DEFORMATION AND EARTHQUAKE POTENTIAL OF THE SOUTHERN LOS ANGELES BASIN, ORANGE COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Award Number: 01HQGR0117 Recipient’s name: University of California - Irvine Sponsored Projects Administration 160 Administration Building, Univ. of CA - Irvine Irvine, CA 92697-1875 Principal investigator: Lisa B. Grant, Ph.D. Department of Environmental Analysis & Design 262 Social Ecology 1 University of California Irvine, CA 92697-7070 Program element: Research on earthquake occurrence and effects Research supported by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Department of the Interior, under USGS award number 01HQGR0117. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Government. p. 1 Award number: 01HQGR0117 ACTIVE DEFORMATION AND EARTHQUAKE POTENTIAL OF THE SOUTHERN LOS ANGELES BASIN, ORANGE COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Eldon M. Gath, University of California, Irvine, 143 Social Ecology I, Irvine, CA, 92697-7070; tel: 949-824-5382, fax: 949-824-2056, email: [email protected] Eric E. Runnerstrom, University of California, Irvine, 143 Social Ecology I, Irvine, CA, 92697- 7070; tel: 949-824-5382, fax: 949-824-2056, email: [email protected] Lisa B. Grant (P.I.), University of California, Irvine, 262 Social Ecology I, Irvine, CA, 92697- 7070; tel: 949-824-5491, fax: 949-824-2056, email: [email protected] TECHNICAL ABSTRACT The Santa Ana Mountains (SAM) are a 1.7 km high mountain range that form the southeastern boundary of the Los Angeles basin between Orange and Riverside counties in southern California. The SAM have three well developed erosional surfaces preserved on them, as well as a suite of four fluvial fill terraces preserved in Santiago Creek, which is a drainage trapped between the uplifting SAM and a parallel Loma Ridge. -

Estimation of Future Earthquake Losses in California

Estimation of Future Earthquake Losses in California B. Rowshandel, M. Reichle, C. Wills, T. Cao, M. Petersen(¨), D. Branum, and J. Davis California Geological Survey Executive Summary Using the latest information on earthquake hazard in California and the publicly available demographic data, we have made estimations of expected future earthquake economic losses in the State. The estimates presented in this paper are for two categories: scenario earthquake loss, and annualized earthquake loss. For scenario earthquake loss, we quantified the damage and loss expected in ten counties in the San Francisco Bay Area (SFBA) and in ten counties in Southern California, due to possible earthquakes on known faults in the two regions. To accomplish this task, we used scenario ground motions, or shake-maps of 50 potential earthquakes published by the United States Geological Survey (USGS). Of these 50 scenario shake-maps, 34 represent the expected ground motion hazard in the SFBA counties and 16 represent the expected ground motion hazard in the southern region. For annualized earthquake loss, we estimated the overall long-term damage and loss using the Probabilistic Seismic Hazard Analysis (PSHA) maps for the State of California, prepared and published by the California Geological Survey (CGS) and the USGS. These PSHA maps show the expected ground motions of specified annual chance of occurrence at any location within the State. The effect on ground motions on the soils at the site are taken into account for both the shake-maps and the PSHA maps, through the use of appropriate ground motion attenuation relations and soil correction factors. Liquefaction effect was taken into account for the annualized loss study, but not for the scenario loss study. -

10066 Report.Pdf

Subsurface Evidence for the Puente Hills and Compton-Los Alamitos Faults in South-Central Los Angeles 2010 SCEC Annual Report Project # 10066 Robert S. Yeats and Danielle Verdugo Earth Consultants International 1642 E. 4th Street, Santa Ana, CA 92701 Abstract We analyzed well data in the vicinity of a deep exploration campaign in 1973-1975 by American Petrofina Exploration Co. to a maximum depth of 6,477 m (American Petrofina Core Hole 1), twice the depth of data from multichannel seismic profiles used in previous studies. The deeper control of the Compton-Los Alamitos (CLA) and Puente Hills reverse faults based on these wells provides evidence of reverse faulting based on repetition of strata on electric logs, abrupt changes of dipmeter-based attitudes, and offset of events on seismic profiles following Avalon Boulevard and Vermont Avenue. Structure contours on the Puente Hills fault are straightforward, whereas contours on the CLA fault are more complex. The presence of faulting at depth leads to the conclusion that the CLA and Puente Hills reverse faults change upward into fault-propagation folds rather than fault-bend folds. The CLA fault marks the northeastern boundary of a broad anticline, called here the Central Uplift anticline, cut along its crest by the right-lateral strike-slip Potrero fault in the vicinity of our study. Structure contours at depth confirm the observations of others that the CLA fault swings westward and steepens in dip toward the NIFZ south of Inglewood oil field. The presence of reverse- fault-plane solutions along the northern NIFZ and evidence for uplift along the CLA fault east of Long Beach and Seal Beach oil fields during the 1933 Long Beach earthquake support an interpretation of faulting along the Newport- Inglewood trend related to strain partitioning, indicating that the NIFZ might generate a Coalinga-type reverse fault as well as a strike-slip event similar to the 1933 earthquake. -

APPENDIX 4.6 Geology and Soils APPENDIX 4.6.1 Fault Rupture Study

APPENDIX 4.6 Geology and Soils APPENDIX 4.6.1 Fault Rupture Study Prepared for: Pacifica Services, Inc. 106 South Mentor Avenue, Suite 200 Pasadena, California 91106 FAULT RUPTURE HAZARD EVALUATION IN SUPPORT OF DRAFT EIR INGLEWOOD TRANSIT CONNECTOR PROJECT INGLEWOOD, CALIFORNIA Prepared by: 16644 West Bernardo Drive, Suite 301 San Diego, California 92127 Project Number: HPA1043-05 27 September 2019 i FAULT RUPTURE HAZARD EVALUATION IN SUPPORT OF DRAFT EIR Inglewood Transit Connector Project Inglewood, California This report was prepared under the supervision and direction of the undersigned. Prepared by: Geosyntec Consultants, Inc. 16644 West Bernardo Drive, Suite 301 San Diego, CA 92127 Alexander Greene, P.G., C.E.G. Jared Warner, P.G. Senior Principal Engineering Geologist Project Geologist ITC Fault Rupture Eval_20190927.F TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Project Description ...................................................................................... 1 1.2 Objective and Scope of Services ................................................................. 2 2. METHODS ........................................................................................................... 3 3. ALQUIST-PRIOLO EARTHQUAKE FAULT ZONES AND FAULTS............ 4 4. RECORDS REVIEW ........................................................................................... 5 4.1 City of Inglewood Building and Safety Division ....................................... -

Loss Estimates for a Puente Hills Blind-Thrust Earthquake in Los Angeles, California

Loss Estimates for a Puente Hills Blind-Thrust Earthquake in Los Angeles, California a) b) c) Edward H. Field, M.EERI, Hope A. Seligson, M.EERI, Nitin Gupta, c) c) d) Vipin Gupta, Thomas H. Jordan, and Kenneth W. Campbell, M.EERI Based on OpenSHA and HAZUS-MH, we present loss estimates for an earthquake rupture on the recently identified Puente Hills blind-thrust fault beneath Los Angeles. Given a range of possible magnitudes and ground mo- tion models, and presuming a full fault rupture, we estimate the total eco- nomic loss to be between $82 and $252 billion. This range is not only con- siderably higher than a previous estimate of $69 billion, but also implies the event would be the costliest disaster in U.S. history. The analysis has also pro- vided the following predictions: 3,000–18,000 fatalities, 142,000–735,000 displaced households, 42,000–211,000 in need of short-term public shelter, and 30,000–99,000 tons of debris generated. Finally, we show that the choice of ground motion model can be more influential than the earthquake magni- tude, and that reducing this epistemic uncertainty (e.g., via model improve- ment and/or rejection) could reduce the uncertainty of the loss estimates by up to a factor of two. We note that a full Puente Hills fault rupture is a rare event (once every ϳ3,000 years), and that other seismic sources pose signifi- cant risk as well. [DOI: 10.1193/1.1898332] INTRODUCTION Recent seismologic and geologic studies have revealed a dangerous fault system, the Puente Hills blind thrust, buried directly beneath Los Angeles, California (Shaw and Shearer 1999, Shaw et al. -

HOSPITAL Seismic Safety Law

California’s HOSPITAL Seismic Safety Law 2005 Its History, Implementation, & Progress Office of Statewide Health Planning & Development California’s Hospital Seismic Safety Law Its History, Implementation and Related Issues Table of Contents California’s Earthquake History.................................................................. 1 When Will the Next One Hit? ..................................................................... 6 How Have Californians Responded? ......................................................... 8 Why Hospitals and Not Other Kinds of Structures? ................................. 10 How Vulnerable are California’s Hospitals? ............................................. 11 What is OSHPD Doing to Help Hospitals Comply?.................................. 13 What is the Status of Hospital Compliance? ............................................ 14 How Much is this Entire Program Going to Cost?.................................... 15 Are Strengthened Hospitals Resistant to More than Just Earthquakes? ..................................................................................... 17 Where Do We Go From Here? ................................................................ 18 California’s Earthquake History California has experienced major, catastrophic earthquakes in the past and will certainly experience more in the future. These quakes occurred throughout the state, NOT just in the more commonly perceived “earthquake zones” of Los Angeles and the Bay Area. • Geologic and archaeological evidence shows a long -

Section 6: Earthquakes

Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan Section 6 – Earthquakes City of Newport Beach, California SECTION 6: EARTHQUAKES Table of Contents Why Are Earthquakes A Threat to the City of Newport Beach? ................ 6-1 Earthquake Basics - Definitions.................................................................................................... 6-3 Causes of Earthquake Damage .................................................................................................... 6-7 Ground Shaking .................................................................................................................................................. 6-7 Liquefaction ......................................................................................................................................................... 6-8 Earthquake-Induced Landslides and Rockfalls .......................................................................................... 6-8 Fault Rupture ...................................................................................................................................................... 6-9 History of Earthquake Events in Southern California .................................... 6-9 Unnamed Earthquake of 1769 .................................................................................................................. 6-11 Unnamed Earthquake of 1800 .................................................................................................................. 6-11 Wrightwood Earthquake of December 12, 1812 ............................................................................... -

Source Faults in the Puente Hills and Vicinity: Contribution to the Community Fault Model Robert S

Source Faults in the Puente Hills and Vicinity: Contribution to the Community Fault Model Robert S. Yeats, Eldon M. Gath, Rene Perez, Chris Walls, Tania Gonzalez, and Tom Rockwell Earth Consultants International 150 El Camino Real, Suite 212 Tustin, CA 92780 We combine surface mapping, including fault evaluation reports by Jerry Treiman of CGS, trench excavations by ECI and other firms, subsurface geology based on well data, and tectonic geomorphic expression to show surface and blind faults that are part of the network of earthquake sources that are hazards to metropolitan Los Angeles. The Elsinore fault has a right-lateral strike-slip rate of 5.3-5.9 mm/yr and a total right slip of 8-9 and no more than 12 km, indicating that it could achieve its total displacement at that rate in about 2 m.y. The Elsinore fault splits into two faults. The Chino fault, dips 60° SW and, together with the adjacent Mahala anticline and Ridge syncline, dies out NW in Los Serranos, a suburb of Chino Hills. Its long-term slip rate is 0.7-2 mm/yr based on the age of affected drainage basins and 0.36-0.51 mm/yr for the Holocene based on a trench. Its maximum net oblique slip is 850-1525 m based on offset facies of the Sycamore Canyon Member of the Puente Formation, consistent with the same age of initiation as the Elsinore fault. The Whittier fault splits from the Elsinore fault at a low angle and changes from south side up in the Santa Ana Mountains to north side up in the Puente Hills.