Middlesex University Research Repository an Open Access Repository Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Literature Knows: Forays Into Literary Knowledge Production

Contributions to English 2 Contributions to English and American Literary Studies 2 and American Literary Studies 2 Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Kai Merten (eds.) Merten Kai / What Literature Knows This volume sheds light on the nexus between knowledge and literature. Arranged What Literature Knows historically, contributions address both popular and canonical English and Antje Kley US-American writing from the early modern period to the present. They focus on how historically specific texts engage with epistemological questions in relation to Forays into Literary Knowledge Production material and social forms as well as representation. The authors discuss literature as a culturally embedded form of knowledge production in its own right, which deploys narrative and poetic means of exploration to establish an independent and sometimes dissident archive. The worlds that imaginary texts project are shown to open up alternative perspectives to be reckoned with in the academic articulation and public discussion of issues in economics and the sciences, identity formation and wellbeing, legal rationale and political decision-making. What Literature Knows The Editors Antje Kley is professor of American Literary Studies at FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany. Her research interests focus on aesthetic forms and cultural functions of narrative, both autobiographical and fictional, in changing media environments between the eighteenth century and the present. Kai Merten is professor of British Literature at the University of Erfurt, Germany. His research focuses on contemporary poetry in English, Romantic culture in Britain as well as on questions of mediality in British literature and Postcolonial Studies. He is also the founder of the Erfurt Network on New Materialism. -

Read the Full PDF

Safety, Liberty, and Islamist Terrorism American and European Approaches to Domestic Counterterrorism Gary J. Schmitt, Editor The AEI Press Publisher for the American Enterprise Institute WASHINGTON, D.C. Distributed to the Trade by National Book Network, 15200 NBN Way, Blue Ridge Summit, PA 17214. To order call toll free 1-800-462-6420 or 1-717-794-3800. For all other inquiries please contact the AEI Press, 1150 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 or call 1-800-862-5801. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schmitt, Gary James, 1952– Safety, liberty, and Islamist terrorism : American and European approaches to domestic counterterrorism / Gary J. Schmitt. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8447-4333-2 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-8447-4333-X (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-8447-4349-3 (pbk.) ISBN-10: 0-8447-4349-6 (pbk.) [etc.] 1. United States—Foreign relations—Europe. 2. Europe—Foreign relations— United States. 3. National security—International cooperation. 4. Security, International. I. Title. JZ1480.A54S38 2010 363.325'16094—dc22 2010018324 13 12 11 10 09 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cover photographs: Double Decker Bus © Stockbyte/Getty Images; Freight Yard © Chris Jongkind/ Getty Images; Manhattan Skyline © Alessandro Busà/ Flickr/Getty Images; and New York, NY, September 13, 2001—The sun streams through the dust cloud over the wreckage of the World Trade Center. Photo © Andrea Booher/ FEMA Photo News © 2010 by the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Wash- ington, D.C. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or repro- duced in any manner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. -

Mcginness Phd 2013

University of Dundee DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY On the Function of Ground in Deleuze’s Philosophy Or An Introduction to Pathogenesis McGinness, John Neil Award date: 2013 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY On the Function of Ground in Deleuze’s Philosophy Or An Introduction to Pathogenesis John Neil McGinness 2013 University of Dundee Conditions for Use and Duplication Copyright of this work belongs to the author unless otherwise identified in the body of the thesis. It is permitted to use and duplicate this work only for personal and non-commercial research, study or criticism/review. You must obtain prior written consent from the author for any other use. Any quotation from this thesis must be acknowledged using the normal academic conventions. It is not permitted to supply the whole or part of this thesis to any other person or to post the same on any website or other online location without the prior written consent of the author. -

The Limits of Naturalism and the Metaphysics of German Idealism

1 The Limits of Naturalism and the Metaphysics of German Idealism Sebastian Gardner ‘In einem schwankenden Zeitalter scheut man alles Absolute und Selbständige; deshalb mögen wir denn auch weder ächten Spaß, noch ächten Ernst, weder ächte Tugend noch ächte Bosheit mehr leiden.’ − Nachtwachen von Bonaventura, Dritte Nachtwache One issue above all forces itself on anyone attempting to make sense of the development of German idealism out of Kant. Is German idealism, in the full sense of the term, metaphysical? The wealth of new anglophone, chiefly North American writing on German idealism, particularly on Hegel – characterized by remarkable depth, rigour, and creativity – has put the perennial question of German idealism’s metaphysicality in a newly sharp light, and in much of this new scholarship a negative answer is returned to the question. Recent interpretation of German idealism owes much to the broader philosophical environment in which it has proceeded. Over recent decades analytic philosophy has enlarged its view of the discipline’s scope and relaxed its conception of the methods appropriate to philosophical enquiry, and in parallel to this development analytically trained philosophers have returned to the history of philosophy, the study of which is now regarded by many as a legitimate and important (perhaps even necessary) form of philosophical enquiry. It remains the case, at the same time, that the kinds of philosophical positions most intensively worked on and argued about in non-historical, systematic analytic philosophy are predominantly naturalistic − and thus, on the face of it, not in any immediate and obvious sense receptive to the central ideas of German idealism. -

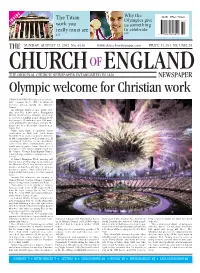

Olympic Welcome for Christian Work

E I D Why the S The Titian IN Olympics give work you us something really must see to celebrate p10 p12 THE SUNDAY, AUGUST 12, 2012 No: 6138 www.churchnewspaper.com PRICE £1.35 1,70j US$2.20 CHURCH OF ENGLAND THE ORIGINAL CHURCH NEWSPAPER ESTABLISHED IN 1828 NEWSPAPER Olympic welcome for Christian work CHRISTIAN GROUPS reported an enthusi- astic response to the different forms of ministry offered during the Olympic Games. An Olympic double-decker ‘praise bus’ that travelled 8,500 miles throughout Britain ahead of the Olympic torch was seen by over 1 million people during its 65- day journey. It contained over 100 musi- cians playing Christian music and was the brainchild of a Methodist Church near Lands End. ‘More than Gold’, a charitable trust established in 2008 with Lord Brian Mawhinney as chair, has urged churches to offer hospitality as well as outreach. It encouraged churches to run hospitality centres near where visitors to the games would pass or gather. Some churches set up giant screens where people could see the Games. Victoria Park Baptist Church reported large numbers coming to see the screen. St John’s, Hampton Wick, handing out bottled water and hot dogs to spectators at the Women’s Cycle race was just one of a number of churches offering refreshment during the games. ‘More than Gold’ set a target of distributing over 1 million cups of water. Around 300 volunteers are serving as Games Pastors at major Olympic transport hubs offering visitors support and help. “Sometimes it is as simple as helping someone make sense of UK money so they have the right change for the loo,” said Mike Freeman MBE, Operations Manager of the Games Pastors Team. -

NEW Hume Web Biblio 26 08 2004.Qxd 01/09/2004 10:39 Page I

NEW Hume web biblio 26_08_2004.qxd 01/09/2004 10:39 Page i A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HUME’S WRITINGS AND EARLY RESPONSES James Fieser NEW Hume web biblio 26_08_2004.qxd 01/09/2004 10:39 Page ii This edition published by Thoemmes Press, 2003 Thoemmes Press 11 Great George Street Bristol BS1 5RR, England http://www.thoemmes.com A Bibliography of Hume’s Writings and Early Responses. © James Fieser, 2003, 2005 NEW Hume web biblio 26_08_2004.qxd 01/09/2004 10:39 Page iii CONTENTS Preface v Major Events in Hume’s Life 1 Bibliography of Hume’s Writings 3 Bibliography of Early Responses to Hume. 65 Index of Authors 181 Index of Topics 203 iii NEW Hume web biblio 26_08_2004.qxd 01/09/2004 10:39 Page iv NEW Hume web biblio 26_08_2004.qxd 01/09/2004 10:39 Page v PREFACE This document contains two separate bibliographies. The first is a “Bibliography of Hume’s Writings” that I constructed for my own benefit while preparing the Early Responses to Hume series. Although it does not merit printed publication in its present state, Thoemmes Press has offered to typeset it at their expense, with the belief that, as a freely available computer file, it will be useful for Hume scholars as it is. It is my hope that someone in the future will prepare a more definitive work of this sort. The second is “A Bibliography of Early Responses to Hume,” which is taken directly from the final pages of Early Responses to Hume’s Life and Reputation (2003). -

City of London Churches Introduction All Hallows by the Tower

City of London Churches Introduction The following pages are a series of written by Mark McManus about some of his favourite churches in the City of London All Hallows by the Tower Barking Abbey, the remains of which still be seen, was founded by Erkenwald in the year 666. Owning land on the eastern edge of the City, the Abbey constructed the Saxon church of All Hallows Berkyngechirche on Tower Hill in 675. Over the centuries, the name mutated to All Hallows Barking. The exterior of the building is quite large and imposing, but its different architectural styles bring attention to its historic troubles: medieval masonry dominated by the brown brickwork of the post-Blitz restoration, its tower of 1659 being a rare example of a Cromwellian rebuild. Despite the somewhat forbidding exterior, the inside of the church is a spacious and light surprise. This is due mostly to Lord Mottistone's post-WWII rebuild, which replaced the previously gloomy Norman nave with concrete and stone, blending well with the medieval work of the aisles with a grace that the cluttered exterior can only dream off. The plain east window allows light to flood into the church, and the glass placed in the recently reopened southern entrance also helps to maintain this airy atmosphere. All Hallows is eager to tell its story. As you first step in through the main entrance in Great Tower Street, you are greeted by a large facsimile showing Vischer's famous engraving of pre- Great Fire London seen from the South Bank, and a gift shop which is the largest I've seen in a City church. -

Introduction: a Great Reversal?

Notes Introduction: A Great Reversal? 1. In their Die Xenien (1797) Schiller and Goethe have some verses which appear to be satirizing a Kantian moral conscience as plagued by the fact that “Gladly I serve my friends, by alas I do it with pleasure”, whereupon it decides that its only resource is “to despise them entirely, and then do with disgust what your duty demands” (Carus, ed., pp. 122–23). If really directed at Kant himself this badly misrepresents his view that the source of an action’s moral worth can most easily be perceived in cases where duty is followed in spite of the subject’s discomfort, which neither implies, nor was taken by Kant to imply, that there is anything necessarily morally compromising in enjoying what duty bids us do. 2. See the Critique of Practical Reason, pp. 114–17 [110–13] and 128–35 [124–31]. 3. Ameriks speaks of Kant’s “great reversal” in Ameriks 1982, p. 226. 4. Julian Young (2005, p. 35) so describes the quest to defend “Kant’s elevated conception of practical reason” after noting with apparent approval Schopenhauer’s view that to think immorality or amorality is inherently irrational is “just silly” and reminding us that Schopenhuaer would have cited Jesus Christ (“a paradigm of rationality?”, Young, p. 35) and Machiavelli (“a paragon of virtue?”, Young, p. 35) as obvious counterexamples. Now there is no doubt that Schopenhauer, like Hume, tended to regard practical irration- ality purely as a matter of failing to take means to gain ends acknowledged as such by the agent, rather than a failure to perceive non-instrumental reasons for not pursuing those ends in the first place (though why that should particularly cast doubt on Christ’s rationality remains unclear to me). -

Soviet Britain Theodore Dalrymple the Road to Real Education

The The quarterly magazine of conservative thought Soviet Britain Piracy Old and Modern Heresies Theodore Dalrymple New Brian Ridley Eric Grove The Road to Real Prince Charles India’s General Education and the Architects Election Charles Brickdale Jan Maciag S V Raju Autumn 2009 £4.99 Vol. 28 No 1 Contents 3 Editorial Articles 4 Soviet Britain 19 Crime as it is Spun Theodore Dalrymple Christie Davies 6 ‘Soviet Medicine’ 21 The Road to Real Education Charles Percival Charles Brickdale 8 Global Meltdown 22 Piracy Jonathan Story Eric Grove 11 Morality and the ‘Bottom Billion’ 25 Prince Charles and the Architects Kenneth Minogue Jan Maciag 14 Modern Heresies in Science 26 Hegel from the Right Brian Ridley Grant Havers 16 15th Indian General Election 28 Front National: an Autopsy S V Raju J L J di Costanzo Columns Arts & Books 38 Ian Crowther 30 Roy Kerridge on John Gray 31 Conservative Classic — 36 39 Sandra Clark Alone in Berlin, Hans Fallada on Milton 33 Reputations — 25 41 Anthony Daniels R G Collingwood on Cybertechnology 35 Future Perfect 42 Clifford Middleton Myles Harris on Secularism 37 Eternal Life 43 Grant Havers Peter Mullen on Nixon, Marcuse et al 44 John Jolliffe on the Quintons 36 Letters 45 Helen Szamuely on Spies 46 Tom Burkard on Truancy 47 Jeremy Worman on Novels 48 Dennis O’Keeffe on The Crash 50 Russell Lewis on Educating the Poor 51 Alistair Miller on Education Today 51 Film: Katharine Szamuely on Katyn 54 Art: Andrew Lambirth on American Art 55 Music: Nigel Jarrett on Vernon Handley 57 In Short The Third Marquis of Salisbury Managing Editor Merrie Cave Consulting Editors Roger Scruton Lord Charles Cecil Myles Harris Mark Baillie Christie Davies Literary Editor Ian Crowther 33 Canonbury Park South, London N1 2JW Tel: 020 7226 7791 Fax: 020 7354 0383 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.salisburyreview.co.uk he great curse of contemporary Britain is the perceptions of the causes of world poverty. -

Norman Kemp Smith's Kant's Critique of Pure Reason Has Become a Classic of Philosophical Translation

From the new Introduction by Howard Caygill: Norman Kemp Smith's Kant's Critique of Pure Reason has become a classic of philosophical translation. Since its first publication in I 929 it has been frequently reprinted, providing an English version of one of the most important and influential texts in the history of philosophy. Kemp Smith's translation made a major contribution not only to the understanding of Kant, but also to the Enlightenment that preceded and the remarkable developments in German philosophy that suc- ceeded him. Kemp Smith's version of the Critique has become the translation of reference, serving as the touchstone of qual- ity not only for subsequent attempts at translation but also, apocryphally, for the original German. The success of the translation is due not only to its eloquence - it manages to translate Kant into the language of Hume- but also to the sense that the translation is itself a philosophical event of considerable significance. CRITIQUE OF PURE REASON IMMANUEL KANT TRANSLATED BY NORMAN KEMP SMITH WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY HOWARD CA YGILL Revised Second Edition BIBLIOGRAPHY COMPILED BY GARY BANHAM pal grave ac il n Translation© the estate of Norman Kemp Smith 1929, 1933, 2003, 2007 Introduction © Howard Caygill 2003, 2007 Bibliography © Gary Banham 2007 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 2nd edition 2007 978-0-230-01337-7 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this * publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, london EC1N 8TS. -

The Modern Theologians: an Introduction to Christian Theology Since 1918

ch The Modern Theologians a pter 1 i The Great Theologians A comprehensive series devoted to highlighting the major theologians of different periods. Each theologian is presented by a world-renowned scholar. Published The Modern Theologians, Third Edition An Introduction to Christian Theology since 1918 David F. Ford with Rachel Muers The Medieval Theologians An Introduction to Theology in the Medieval Period G. R. Evans The Reformation Theologians An Introduction to Theology in the Early Modern Period Carter Lindberg The First Christian Theologians An Introduction to Theology in the Early Church G. R. Evans The Pietist Theologians An Introduction to Theology in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries Carter Lindberg ii The Modern Theologians An Introduction to Christian Theology since 1918 Third Edition Edited by David F. Ford University of Cambridge With Rachel Muers University of Exeter iii © 2005 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd except for editorial material and organization © 2005 by David F. Ford BLACKWELL PUBLISHING 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of David F. Ford to be identified as the Author of the Editorial Material in this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

A Commentary to Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (Classic Reprint) Online

VK9DL (Mobile library) A Commentary to Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (Classic Reprint) Online [VK9DL.ebook] A Commentary to Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (Classic Reprint) Pdf Free Norman Kemp Smith audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #2176902 in Books 2017-02-09 2017-02-09Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.00 x 1.54 x 6.00l, 1.98 #File Name: 1440086923680 pages | File size: 75.Mb Norman Kemp Smith : A Commentary to Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (Classic Reprint) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised A Commentary to Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (Classic Reprint): 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. good reprintBy Lucas SilveiraThis is a REPRINT of the second revised and enlarged edition of 1923, except that it's missing the "Appendix C - Kant's Opus Postumus", which has a little under 40 pages, and the preface to the 2nd edition.The fact that this is a reprint makes the quality of the printing not very good, but at the same time it helps a lot with references and quotations.Overall, for the price and the size of this book, I'm very happy with it.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy Yimin Kuiextremely satisfied with everything, especially .com's new way of international shipping0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Four StarsBy DGLoved it. Excerpt from A Commentary to Kant's Critique of Pure ReasonSecond Edition Statement of the Paralogisms Is the Notion of the Self a necessary Idea of Reason 2'About the PublisherForgotten Books publishes hundreds of thousands of rare and classic books.