City of London Churches Introduction All Hallows by the Tower

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southwark Cathedral Chief Operating Officer

PRIVATE & CONFIDENTIAL Candidate Brief Southwark Cathedral Chief Operating Officer U1201 January 2021 Managing Director Sarah Thewlis [email protected] Southwark Cathedral – Chief Operating Officer – U1201 Contents 1. Welcome letter from The Very Revd Andrew Nunn, Dean 2. About Southwark Cathedral 3. The Job Description and Key Responsibilities of the Chief Operating Office 4. Remuneration and Benefits 5. Timeline, Application Process and How to apply 6. Advert 2 Southwark Cathedral – Chief Operating Officer – U1201 Welcome from The Very Revd Andrew Nunn Dean of Southwark Dear Candidate, I am delighted that you have expressed an interest in applying to be the Chief Operating Officer of Southwark Cathedral. We hope that you find the information useful in this candidate brief and also on our website: https://cathedral.southwark.anglican.org/ The Cathedral Chapter is looking to appoint a full-time Chief Operating Officer to lead and contribute across a number of strategic and managerial aspects of Cathedral life. They will drive and manage the delivery of the Cathedral’s strategy and will work with the Chapter to ensure that the Cathedral is effectively and efficiently run and is able to deliver our mission priorities. The successful candidate will report to the Dean, have oversight of all operations within the Cathedral, provide support to the Chapter in its strategic planning, and be responsible for finance, governance, administration, property and for staff who are employed to support the Cathedral’s work. They will be instrumental in amending the governance structures to conform to the new Cathedral Measure that must be completed by mid-2023. They will need to have experience of being responsible for a broad range of operational functions, an understanding of working within a complex governance and charitable structure, and the desire and motivation to support and encourage a strong sense of community. -

“Accompt of Writing Belonging to Me Pet. Burrell” Notes on Marriage, Birth and Death 1687 - 1704

“Accompt of Writing belonging to me Pet. Burrell” Notes on marriage, birth and death 1687 - 1704 Introduction During a research visit to the Kent History and Library Centre in October 2019, the bundle “MANORIAL DOCUMENTS AND DEEDS (1250-1927)” was ordered. The documents related to the Burrell family of Beckenham, Kent. My role was “research assistant” to my husband, Keith, who was working on deeds and leases relating to Shortlands House and Estate in the 17th and 18th centuries (see “Shortlands House and Estate 14th – 21st Century”). Peter Burrell 1649/50 – 1718 ©Kent Archives Ref: U36/F1 Reproduced by kind permission ©Burrell Family Collection/Knepp Castle One of the items in the bundle was U36/F1 “Burrell family – account book of Peter Burrell, including account of rents 1687-1694, repairs at Beckenham (no details) 1692; lands purchased 1698-1704, notes on birth and death of children 1687-1701”. It was a small notebook containing an inscription stating that it was the property of Peter Burrell. The first 61 “folios” (double pages), neatly detailed the who, when and what of financial and land transactions. These I duly transcribed to confirm the dates and names of owners and tenants detailed various purchases, sales and exchanges of fields, houses, farms and estates. This appeared to be the end of the accounts and there was a handy index of names at the back of the book. However, leafing past the blank pages, I came to pages crowded with less carefully penned writing, with continuations in margins and marks indicating where, having run out of room on one folio, Peter had continued an entry on another page. -

Job Spec: Lay Missioner-Evangelist for City of London Parish St Andrew

City Deanery Job Spec: Lay Missioner-Evangelist for City of London Parish St Andrew-by-the-Wardrobe Prepared by: The Rev. Guy Treweek Wednesday, 29 May 2013 St Andrew-by-the-Wardrobe Corner of Queen Victoria Street & St Andrew’s Hill, London EC4V 5DE T 020 7248 7546 [email protected] ST ANDREW BY THE WARDROBE Executive Summary St Andrew-by-the-Wardrobe wishes to appoint a Lay Missioner-Evangelist to reach out to a large midweek working community. Context To properly understand where this submission fits in achieving St Andrew’s wider strategic aims, it is important that this application be read together with our overarching strategy document, A Growing Vision: Towards a Mission Action Plan (attached). Term Three years. Lay Missioner-Evangelist Job Spec 1 ST ANDREW BY THE WARDROBE Supporting Detail Background St Andrew-by-the-Wardrobe is a parish church in the City of London. It encompasses the area to the south of St Paul’s Cathedral and north of the river Thames. Two underground & mainline stations are in the parish (Blackfriars & City Thameslink) giving massive throughput of City workers (c. 25 million entries & exits in a year). This is expected to increase yet further as Crossrail comes online. The parish contains the northern end of the Millennium Bridge, which is now the largest entry point into the City (overtaking St Paul’s underground station). In the north of the parish, the Carter Lane / Ludgate Hill area is seeing considerable development as a “go to” destination for night-time socialising, with new bars, restaurants and a five-star hotel. -

In SE1 April 2003

The essential monthly guide to what’s on in SE1 www.inSE1.co.uk April 1 SE Issue 58 April 2003 in Free Thumbs up for C-Charge MORE THAN three-quarters of now often enjoy a clear run those responding to a poll on down Farringdon Street and the London SE1 community over Blackfriars Bridge into website are in favour of the SE1. Transport for London Congestion Charge. has issued guidance to bus This figure reflects the managers allowing them to views in other parts of central ignore the timetable rather London although the scheme than keep buses waiting. is thought to have been less •Bristol Industrial Museum’s successful around King’s 105-year-old Daimler Cross on the boundary. which hasn’t been on the A massive 77% replied road since 1947 has had a “yes’ when asked ‘Has the penalty notice for evading congestion charge had a the congestion charge in HOLY WEEK begins in Borough Market. Southwark positive impact on life in SE1?’ London Road, SE1. The Cathedral’s Palm Sunday Procession will begin in the Just 12% said “no” whilst 13% car has a maximum speed Market at 11am on Sunday 13 April. After the blessing of were undecided. of only 15mph. TfL said palms and the reading of the Gospel, the procession will Many people report buses “It would be ridiculous to make its way along Bedale Street for the Sung Eucharist. running faster than before expect there are not going the charge. Routes 63 and 45 to be individual errors.” The Coronet reopens at last LONDON’S MAJOR new as well as live performances. -

The Midwives of Seventeenth-Century London

The Midwives of Seventeenth-Century London DOREEN EVENDEN Mount Saint Vincent University published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb22ru, uk http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de AlarcoÂn 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain q Doreen Evenden 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United States of America bv Typeface Bembo 10/12 pt. System DeskTopPro/ux [ ] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data Evenden, Doreen. The midwives of seventeenth-century London / Doreen Evenden. p. cm. ± (Cambridge studies in the history of medicine) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-521-66107-2 (hc) 1. Midwives ± England ± London ± History ± 17th century. 2. Obstetrics ± England ± London ± History ± 17th century. 3. Obstetricians ± England ± London ± History ± 17th century. 4. n-uk-en. I. Title. II. Series. rg950.e94 1999 618.2©09421©09032 ± dc21 99-26518 cip isbn 0 521 66107 2 hardback CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures page xiii Acknowledgements xv List of Abbreviations xvii Introduction 1 Early Modern Midwifery Texts 6 The Subjects of the Study 13 Sources and Methodology 17 1 Ecclesiastical Licensing of Midwives 24 Origins of Licensing 25 Oaths and Articles Relating to the Midwife's Of®ce 27 Midwives and the Churching Ritual 31 Acquiring a Licence 34 Midwives at Visitations 42 2 Pre-Licensed Experience 50 Length of Experience 50 Deputy Midwives 54 Matrilineal Midwifery Links 59 Senior Midwives 62 Midwives' Referees 65 Competence vs. -

ST. PAUL's CATHEDRAL Ex. Par ALL HALLOWS, BERKYNCHIRCHE-BY

ST. JAMES AND ST. JOHN WITH ST. PETER, CLERKENWELL ST. LEONARD WITH ST. MICHAEL, SHOREDITCH TRINITY, HOLBORN AND ST. BARTHOLOMEW, GRAY'S INN ROAD ST. GILES, CRIPPLEGATE WITH ST. BARTHOLOMEW, MOOR LANE, ST. ALPHAGE, LONDON WALL AND ST. LUKE, OLD STREET WITH ST. MARY, CHARTERHOUSE AND ST. PAUL, CLERKE CHARTERHOUSE ex. par OBURN SQUARE CHRIST CHURCH WITH ALL SAINTS, SPITALF ST. BARTHOLOMEW-THE-GREAT, SMITHFIELD ST. BARTHOLOMEW THE LESS IN THE CITY OF LONDON ST. BOTOLPH WITHOUT BISHOPSGATE ST. SEPULCHRE WITH CHRIST CHURCH, GREYFRIARS AND ST. LEONARD, FOSTER LANE OTHBURY AND ST. STEPHEN, COLEMAN STREET WITH ST. CHRISTOPHER LE STOCKS, ST. BARTHOLOMEW-BY-THE-EXCHANGE, ST. OLAVE, OLD JEWRY, ST. MARTIN POMEROY, ST. MILD ST. HELEN, BISHOPSGATE WITH ST. ANDREW UNDERSHAFT AND ST. ETHELBURGA, BISHOPSGATE AND ST. MARTIN OUTWICH AND ST. PAUL'S CATHEDRAL ex. par ST. BOTOLPH, ALDGATE AND HOLY TRINITY, MINORIES ST. EDMUND-THE-KING & ST. MARY WOOLNOTH W ST. NICHOLAS ACONS, ALL HALLOWS, LOMBARD STREET ST. BENET, GRACECHURCH, ST. LEONARD, EASTCHEAP, ST. DONIS, BA ST. ANDREW-BY-THE-WARDROBE WITH ST. ANN BLACKFRIARS ST. CLEMENT, EASTCHEAP WITH ST. MARTIN ORGAR ST. JAMES GARLICKHYTHE WITH ST. MICHAEL QUEENHITHE AND HOLY TRINITY-THE-LESS T OF THE SAVOY ex. par ALL HALLOWS, BERKYNCHIRCHE-BY-THE-TOWER WITH ST. DUNSTAN-IN-THE-EAST WITH ST. CLEMENT DANES det. 1 THE TOWER OF LONDON ST. PETER, LONDON D Copyright acknowledgements These maps were prepared from a variety of data sources which are subject to copyright. Census data Source: National Statistics website: www.statistics.gov.uk -

Smithfield Market but Are Now Largely Vacant

The Planning Inspectorate Report to the Temple Quay House 2 The Square Temple Quay Secretary of State Bristol BS1 6PN for Communities and GTN 1371 8000 Local Government by K D Barton BA(Hons) DipArch DipArb RIBA FCIArb an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State Date 20 May 2008 for Communities and Local Government TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 PLANNING (LISTED BUILDINGS AND CONSERVATION AREAS) ACT 1990 APPLICATIONS BY THORNFIELD PROPERTIES (LONDON) LIMITED TO THE CITY OF LONDON COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT AT 43 FARRINGDON STREET, 25 SNOW HILL AND 29 SMITHFIELD STREET, LONDON EC1A Inquiry opened on 6 November 2007 File Refs: APP/K5030/V/07/1201433-36 Report APP/K5030/V/07/1201433-36 CONTENTS SECTION TITLE PAGE 1.0 Procedural Matters 3 2.0 The Site and Its Surroundings 3 3.0 Planning History 5 4.0 Planning Policy 6 5.0 The Case for the Thornfield Properties (London) 7 Limited 5.1 Introduction 7 5.2 Character and Appearance of the Surrounding Area 8 including the Settings of Nearby Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas 5.3 Viability 19 5.4 Repair, maintenance and retention of the existing buildings 23 5.5 Sustainability and Accessibility 31 5.6 Retail 31 5.7 Transportation 32 5.8 Other Matters 33 5.9 Section 106 Agreement and Conditions 35 5.10 Conclusion 36 6.0 The Case for the City of London Corporation 36 6.1 Introduction 36 6.2 Character and Appearance of the Surrounding Area 36 including the Settings of Nearby Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas 6.3 Viability 42 6.4 Repair, maintenance and retention of the existing buildings -

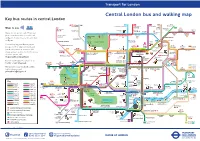

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

Read the Full PDF

Safety, Liberty, and Islamist Terrorism American and European Approaches to Domestic Counterterrorism Gary J. Schmitt, Editor The AEI Press Publisher for the American Enterprise Institute WASHINGTON, D.C. Distributed to the Trade by National Book Network, 15200 NBN Way, Blue Ridge Summit, PA 17214. To order call toll free 1-800-462-6420 or 1-717-794-3800. For all other inquiries please contact the AEI Press, 1150 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 or call 1-800-862-5801. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schmitt, Gary James, 1952– Safety, liberty, and Islamist terrorism : American and European approaches to domestic counterterrorism / Gary J. Schmitt. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8447-4333-2 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-8447-4333-X (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-8447-4349-3 (pbk.) ISBN-10: 0-8447-4349-6 (pbk.) [etc.] 1. United States—Foreign relations—Europe. 2. Europe—Foreign relations— United States. 3. National security—International cooperation. 4. Security, International. I. Title. JZ1480.A54S38 2010 363.325'16094—dc22 2010018324 13 12 11 10 09 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cover photographs: Double Decker Bus © Stockbyte/Getty Images; Freight Yard © Chris Jongkind/ Getty Images; Manhattan Skyline © Alessandro Busà/ Flickr/Getty Images; and New York, NY, September 13, 2001—The sun streams through the dust cloud over the wreckage of the World Trade Center. Photo © Andrea Booher/ FEMA Photo News © 2010 by the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Wash- ington, D.C. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or repro- duced in any manner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. -

Aldersgate Street London EC1A 4JQ

124 Aldersgate Street London EC1A 4JQ Charming self-contained Charming self-contained warehouse style office warehouse style office freehold with its own freehold with its own courtyard & rear garden courtyard & rear garden For Sale For Sale The Opportunity • Character Clerkenwell freehold, close to Smithfield, Farringdon and Barbican • Converted warehouse office building comprising a Net Internal Area of 4,981 sq ft (462.7 sq m) and a Gross Internal Area of 6,173 sq ft (573.5 sq m) • B1 officese u throughout • Exclusive private gated courtyard providing secure car parking for up to 3 cars • Secluded rear walled garden of approx. 1,500 sq ft • Attractive 1st floor terrace of approx. 600 sq ft • Potential to extend subject to securing the necessary consents • Sold with vacant possession on completion • Offers are invited for the freehold interest to include the front courtyard & rear garden Garden Lower Ground Floor Ground Floor Ground Floor Front Entrance The Location Connectivity The building sits in a cul-de-sac off Aldersgate Street with Charterhouse Square to the Barbican Station is within a minutes walk giving access to the Circle, west and Carthusian Street to the south. Clerkenwell Road is 300 metres to the north. Hammersmith & City and Metropolitan Lines. Farringdon Station is within 500 metres (7 minute walk) and is served by the same Tube lines, The immediate area benefits from the amenities of Smithfield Market and Clerkenwell Thameslink and Crossrail (from 2018). St Paul’s Station is a 10 minute walk Green, with a plethora of shops, bars and restaurants. The Barbican Centre, London to the south providing access to the Central Line. -

Chapter 2 - the Search for William Atterbury's Parents

William Atterbury (1711-1766) - The Family Patriarch and His Legacy Chapter 2 - The Search for William Atterbury's Parents This work will investigate the ancestry and descendants of a person named William Atterbury, who was born in London, England in 1711 (author's assumed date), who was transported a convict from New Gate Prison to Annapolis Maryland in 1733, and who died in Loudoun County Virginia in about 1766. This William Atterbury was the progenitor of the author's family and of most Atteberrys living in America today. In the pursuit of this research into the William Atterbury family in America the author has found only three other published works to exist on Atterbury families in America: 1. In 1933 L. Effingham de Forest and Anne Lawrence de Forest published a book entitled The Descendants of Job Atterbury.1 That work presents the genealogy of Job Atterbury, who first appeared in American records when some of his children were recorded born in New Jersey starting in 1795. The de Forests represent Job Atterbury to have been the first of that surname to have settled in America. Such assertion is clearly incorrect as there are records of several other earlier Atterburys. This will be the last mention of Job Atterbury and his descendants, as there is no known connection to the William Atterbury family. 2. In 1984 Voncille Attebery Winter, PhD. and Wilma Attebery Mitchell, self published their work entitled The Descendants of William Atterbury, 1733 Emigrant.2 The Winter- Mitchell book culminated many years of research by these William Atterbury descendants, and was the single, most comprehensive document found by the author to have been written on this family. -

2. the Statement of Significance Discloses That Reference Was First

IN THE CONSISTORY COURT OF THE DIOCESE OF LONDON RE: ST STEPHEN W ALBROOK Faculty Petition dated 1 May 2012 Faculty Ref: 2098 Proposed Disposal by sale of Benjamin West painting, 'Devout Men Taking the Body of St Stephen' JUDGMENT 1. By a petition dated 1 May 2012 the Priest-in-Charge and churchwardens of St Stephen Walbrook and St Swithin London Stone with St Benet Sherehog and St Mary Bothaw with St Lawrence Pountney seek a faculty to authorise: "the disposal by sale of a painting by Benjamin West depicting 'Devout Men taking the body ofSt Stephen'". The proposal has the unanimous support of the Parochial Church Council but it is not recommended by the Diocesan Advisory Committee. General citation took place between 15 March and 18 Apri12012 and no objections were received from parishioners or members of the public. No objections were received from English Heritage or the Local Planning Authority (who were both notified of the proposal). The Ancient Monument Society, although consulted and invited to attend the directions and subsequent hearings, indicated that it did not wish to be involved. Initially, the Church Buildings Council (CBC), having advised against the proposals and agreeing with the views of the DAC, stated that it would not wish formally to oppose the petition but it subsequently changed its mind and was given leave by me to become a Party Opponent out of time. The Georgian Group objected from the outset and, having initially indicated it wished to be a Party Opponent, subsequently agreed to its interests being represented at the hearing by the CBC.