Comments of the National Coalition for Advanced Transportation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ELECTRIC VEHICLES MARKET IS POWERING up an Industry Snapshot

Investment and Company Research Opportunity Research INDUSTRY SNAPSHOT July 2, 2020 ELECTRIC VEHICLES MARKET IS POWERING UP An Industry Snapshot Featured Companies: Tesla (NASDAQ - TSLA); Nikola (NASDAQ – NKLA); Workhorse Group (NASDAQ – WKHS); Alternet Systems (OTC – ALYI) www.goldmanresearch.com Copyright © Goldman Small Cap Research, 2020 Page 1 of 8 Investment and Company Research Opportunity Research INDUSTRY SNAPSHOT OUR THESIS: As of this writing, shares of Tesla (NASDAQ – TSLA), the undisputed bellwether stock for the electric vehicle market trades at $1121 per share. At current prices, the market cap is over $207 billion, representing over 5 estimated 2021 sales and a whopping 98x next year’s EPS. In many investors’ minds, where Tesla goes, so goes the industry segment, especially as it relates to the capital markets. While TSLA is the industry’s most important company, it is the exact mid-point of 2020, not 2016, and therefore is not the only pubco in the space. In fact, some under the radar firms with exposure to the space offer major upside that may rival TSLA, with varying risk profiles and share prices. Instead of making the case for the industry and its constituents in the lithium, fuel cell, and other segments, we have elected to focus on the vehicle producers, where we believe the greatest attention and upside exist. THE EV MARKET: A BRIEF HISTORY We began writing about the EV market in 2015/2016 and while going over our old reports and blogs, we came across some striking information. In 2016, Bloomberg New Energy Finance (now billed as Bloomberg NEF) projected that by 2040, EV passenger sales will reach 41 million units. -

Advanced Technology Equipment Manufacturers*

Advanced Technology Equipment Manufacturers* Revised 04/21/2020 On-Road (Medium/Heavy Duty, Terminal Tractors) OEM Model Technology Vocations GVWR Type Altec Industries, Inc Altec 12E8 JEMS ePTO ePTO ePTO, Utility > 33,000, 26,001 - 33,000 New Altec Industries, Inc Altec JEMS 1820 and 18E20 ePTO ePTO ePTO, Utility > 33,000, 26,001 - 33,000 New Altec Industries, Inc Altec JEMS 4E4 with 3.6 kWh Battery ePTO ePTO, Utility 16,001-19,500, 19,501-26,000 New Altec Industries, Inc Altec JEMS 6E6 with 3.6 kWh Battery ePTO ePTO, Utility 16,001-19,500, 19,501-26,000 New Autocar Autocar 4x2 and 6x4 Xpeditor with Cummins-Westport ISX12N Engine Near-Zero Engine Truck > 33,001 New Autocar Autocar 4x2 and 6x4 Xpeditor with Cummins-Westport L9N Engine Near-Zero Engine Refuse > 33,001 New Blue Bird Blue Bird Electric Powered All American School Bus Zero Emission Bus, School Bus > 30,000 New Blue Bird Blue Bird Electric Powered Vision School Bus 4x2 Configuration Zero Emission Bus, School Bus > 30,000 New BYD Motors BYD 8Y Electric Yard Tractor Zero Emission Terminal Truck 81,000 New BYD Motors BYD C10 45' All-Electric Coach Bus Zero Emission Bus 49,604 New BYD Motors BYD C10MS 45' All-Electric Double-Decker Coach Bus Zero Emission Transit Bus 45' New BYD Motors BYD C6 23' All-Electric Coach Bus Zero Emission Bus 18,331 New BYD Motors BYD K11 60' Articulated All-Electric Transit Bus Zero Emission Bus 65,036 New BYD Motors BYD K7M 30' All-Electric Transit Bus Zero Emission Bus, Transit Bus 30' New BYD Motors BYD K9 40' All-Electric Transit Bus Zero Emission -

11 Electric Vehicle Stocks to Buy for 2021

INVESTOR PLACE 11 ELECTRIC VEHICLE STOCKS TO BUY FOR 2021 LUKE LANGO How to turn the electric disruption of transportation into your million-dollar opportunity When it comes to identifying next-generation breakthrough investments that could rise 100%, 200%, 500%, or more, I always come back to one saying. Where there’s disruption, there’s opportunity. Case-in-point: The internet. Throughout the 1990s, the emergence of the internet rapidly disrupted how people across the globe worked, communicated, and played. For many, it was a scary time. Change is never easy. For many more, it was an exciting time, as the internet was unlocking a new world of possibilities. But… for investors… it was an opportunity. Specifically, it was a once-in-a-decade opportunity to invest early in emerging titans of the internet industry. Like Amazon (AMZN)… when it was a $438 million company in 1997… It’s a $1.6 TRILLION company today – representing a whopping 365,000% return. That means a mere $1,000 investment in Amazon in 1997 would be worth more than $3.6 million today. 2 Luke Lango’s Hypergrowth Investing Need I say more? Where there’s disruption, there’s opportunity – and the bigger the disruption, the bigger the opportunity. Right now, we are on the cusp of an enormous disruption. This disruption will fundamentally and entirely change the world’s multi-trillion-dollar transportation work. In its wake, it will create new hundred-billion-dollar titans of the auto industry – most of whom are just tiny companies today. What disruption am I talking about specifically? The shift toward electric vehicles. -

GM Sells Shuttered Ohio Assembly Plant to Electric Vehicle Startup by David Welch November 7, 2019, 3:10 PM EST

Hyperdrive GM Sells Shuttered Ohio Assembly Plant to Electric Vehicle Startup By David Welch November 7, 2019, 3:10 PM EST Lordstown Motors is still raising money for its plug-in pickup CEO Steve Burns says he hopes to start production in late 2020 rally-goers from selling their homes because of all the jobs he would bring back to the area. Democrats seized on the development as a symbol of unfulfilled promises made to voters in a key battleground state. Trump was so eager to endorse GM’s discussions to sell the Lordstown plant that he preempted the announcement of the talks in May by the largest U.S. automaker and Workhorse. But both companies are on shaky financial footing, with Workhorse totaling just $6,000 of revenue during its latest quarter. American flags fly in front of the GM plant in Lordstown, Ohio, in March. The automaker has sold the factory to Lordstown Motors. Lordstown Motors Corp., the electric-truck startup formed specifically to save a shuttered Ohio car factory, has acquired the highly politicized plant from General Motors Co. The acquisition that the two companies announced Thursday ends an era that began when GM opened the complex in 1966. The factory’s fate was largely sealed when the United Auto Workers union was unable to convince GM to keep it in the fold as part of a new labor contact ratified late last month. With the plant acquisition out of the way, Steve Burns, who Terms of the deal aren’t being disclosed. Workhorse Group used to lead Workhorse and is now chief executive officer Inc., which is affiliated with Lordstown Motors but doesn’t of Lordstown Motors, is turning his attention to phase two: share any ownership, soared 27% to close at $3.13 in New seeking cash to convert the Lordstown plant from making York trading. -

DWS Small Cap Index VIP

Investment Portfolio as of September 30, 2020 (Unaudited) DWS Small Cap Index VIP ______________________Shares Value ($) Common Stocks 98.6% Communication Services 2.3% Diversified Telecommunication Services 0.8% Alaska Communications Systems Group, Inc. 9,664 19,328 Anterix, Inc.* 1,751 57,275 ATN International, Inc. 2,052 102,887 Bandwidth, Inc. "A"* 3,387 591,268 Cincinnati Bell, Inc.* 8,969 134,535 Cogent Communications Holdings, Inc. 7,403 444,550 Consolidated Communications Holdings, Inc.* 12,394 70,522 IDT Corp. "B"* 3,076 20,240 Iridium Communications, Inc.* 20,284 518,865 Liberty Latin America Ltd. "A"* 8,472 69,894 Liberty Latin America Ltd. "C"* 27,483 223,712 Ooma, Inc.* 3,608 47,084 Orbcomm, Inc.* 12,899 43,857 Vonage Holdings Corp.* 39,742 _________406,561 2,750,578 Entertainment 0.2% AMC Entertainment Holdings, Inc. "A" (a) 9,254 43,586 Cinemark Holdings, Inc. (a) 19,171 191,710 Eros STX Global Corp* (a) 23,773 52,538 Gaia, Inc.* 2,099 20,633 Glu Mobile, Inc.* 24,816 190,463 IMAX Corp.* 8,860 105,966 Liberty Media Corp.-Liberty Braves "A"* 1,868 39,004 Liberty Media Corp.-Liberty Braves "C"* 6,415 134,779 LiveXLive Media, Inc.* 7,885 20,462 Marcus Corp. 3,616 _________27,952 827,093 Interactive Media & Services 0.4% Cargurus, Inc.* 14,792 319,951 Cars.com, Inc.* 12,057 97,420 DHI Group, Inc.* 9,464 21,389 Eventbrite, Inc. "A"* (a) 11,367 123,332 EverQuote, Inc. "A"* 2,494 96,368 Liberty TripAdvisor Holdings, Inc. -

Usef-I Q2 2021

Units Cost Market Value U.S. EQUITY FUND-I U.S. Equities 88.35% Domestic Common Stocks 10X GENOMICS INC 5,585 868,056 1,093,655 1ST SOURCE CORP 249 9,322 11,569 2U INC 301 10,632 12,543 3D SYSTEMS CORP 128 1,079 5,116 3M CO 11,516 2,040,779 2,287,423 A O SMITH CORP 6,897 407,294 496,998 AARON'S CO INC/THE 472 8,022 15,099 ABBOTT LABORATORIES 24,799 2,007,619 2,874,948 ABBVIE INC 17,604 1,588,697 1,982,915 ABERCROMBIE & FITCH CO 1,021 19,690 47,405 ABIOMED INC 9,158 2,800,138 2,858,303 ABM INDUSTRIES INC 1,126 40,076 49,938 ACACIA RESEARCH CORP 1,223 7,498 8,267 ACADEMY SPORTS & OUTDOORS INC 1,036 35,982 42,725 ACADIA HEALTHCARE CO INC 2,181 67,154 136,858 ACADIA REALTY TRUST 1,390 24,572 30,524 ACCO BRANDS CORP 1,709 11,329 14,749 ACI WORLDWIDE INC 6,138 169,838 227,965 ACTIVISION BLIZZARD INC 13,175 839,968 1,257,422 ACUITY BRANDS INC 1,404 132,535 262,590 ACUSHNET HOLDINGS CORP 466 15,677 23,020 ADAPTHEALTH CORP 1,320 39,475 36,181 ADAPTIVE BIOTECHNOLOGIES CORP 18,687 644,897 763,551 ADDUS HOMECARE CORP 148 13,034 12,912 ADOBE INC 5,047 1,447,216 2,955,725 ADT INC 3,049 22,268 32,899 ADTALEM GLOBAL EDUCATION INC 846 31,161 30,151 ADTRAN INC 892 10,257 18,420 ADVANCE AUTO PARTS INC 216 34,544 44,310 ADVANCED DRAINAGE SYSTEMS INC 12,295 298,154 1,433,228 ADVANCED MICRO DEVICES INC 14,280 895,664 1,341,320 ADVANSIX INC 674 15,459 20,126 ADVANTAGE SOLUTIONS INC 1,279 14,497 13,800 ADVERUM BIOTECHNOLOGIES INC 1,840 7,030 6,440 AECOM 5,145 227,453 325,781 AEGLEA BIOTHERAPEUTICS INC 287 1,770 1,998 AEMETIS INC 498 6,023 5,563 AERSALE CORP -

Workhorse Group, INC--The Small Cincinnati Company “Delivering” in the Electric Vehicle Race

June 2020 Will Brown Adam Eagleston CEO and Managing Partner CIO Workhorse Group, INC--The Small Cincinnati Company “Delivering” in the Electric Vehicle Race It is rare to find a company at the intersection of two major trends; it’s even more unusual that it is in your hometown. However, that is the case with the aptly named Workhorse Group, Inc. (ticker: WKHS) headquartered in Loveland, OH. Formidable Asset Management (“FAM”) recently established a position; following are the key pieces of our investment thesis: • Established technology and infrastructure • Marquee customers • Undervalued investments Overview Workhorse manufactures electric vehicles (both land-based and aerial), predominantly for use in deliveries (think Amazon, UPS, or the U.S. Postal Service). Despite its presence in this attractive niche, valuable intellectual property, and potentially transformative strategic partnerships, the company trades at a significant discount to our estimate of its intrinsic value. Established technology and infrastructure The company builds more than electric vehicles; it has developed an integrated platform to offer clients a holistic delivery solution that includes cost efficient ground vehicles, telematics to optimize deliveries, and unmanned aerial systems (UASs) for last mile delivery. In the company’s opinion, it is a first mover with a two-to-three year head start over its competitors, which is critically important. Once established, it is very difficult to displace an incumbent within the context of a vehicle fleet, especially one that is integrated. The company has seven (7) granted and four (4) pending patents. As we’ll see later, some of Workhorse’s core electric vehicle intellectual property is currently being licensed. -

Heavy-Duty Vehicles & Freight Sector Baseline

Heavy-duty Vehicles & Freight Sector Baseline ALLIANCE 50X50 COMMISSION ON U.S. TRANSPORTATION SECTOR EFFICIENCY Report by the Heavy-duty Vehicles & Freight Technical Committee September 26, 2018 PREAMBLE The Alliance to Save Energy launched the 50x50 Commission on U.S. Transportation Sector Efficiency (the “50x50 Commission”) to lay out regulatory, policy, and investment pathways to significantly improve energy efficiency in the U.S. transportation sector. Comprising executives and decision makers from a range of key stakeholder groups— including vehicle manufacturers, utilities, federal and subnational governments, technology developers and providers, environmental advocates, and targeted customers— the 50x50 Commission established the goal to reduce energy consumption in the U.S. transportation sector by 50 percent by 2050 on a pump-to-wheel (PTW) basis, relative to a 2016 baseline. The 50x50 Commission work is complementary to that of the Alliance Commission on National Energy Efficiency Policy, which recommended energy efficiency policies and practices that could lead to a second doubling of energy productivity by 2030. As transportation represents roughly one-third of overall energy consumption in the U.S., the transportation sector offers enormous potential for gains in both energy efficiency and energy productivity. The outputs of the 50x50 Commission include a foundational white paper that outlines the goals and scope of the Commission’s work, a set of five “sector baseline” reports that assess the current state of energy efficiency within the transportation sector, and a suite of policy recommendations outlining the types of government support, at all levels, necessary to achieve the 50x50 goal. This report, Heavy-duty Vehicles & Freight, is one of the five sector baseline reports that identifies the general market trends for efficient transportation technologies and explores opportunities and challenges related to deploying those technologies. -

Chip Dip Hits Automakers

Money&Markets Extra LocalStocks LocalFunds 52-WK RANGE FRIDAY $CHG 52-WK RANGE FRIDAY $CHG $CHG %RTN/RANK COMPANY TICKER LOW HIGH CLOSE 1WK PE DIV YLD COMPANY TICKER LOW HIGH CLOSE 1WK PE DIV YLD FAMILY FUND TICKER NAV 1WK 1YR 5YRS* AMC Entertainment A AMC 1.91 72.62 37.19 -1.27 ... ... ... IBM IBM 105.92 152.84 143.22 -0.10 24 6.56 4.6 American Century UltraInv TWCUX 87.84 +0.27 +28.2/B +25.5/A AT&T Inc T 26.35 33.88 26.77 0.13 ... 2.08 7.8 Johnson Controls Int JCI 40.92 76.83 69.01 -0.01 48 1.08 1.6 American Funds GrfAmrcA m AGTHX 76.79 +0.32 +28.3/A +20.1/D InvCAmrcA m AIVSX 51.17 +0.54 +27.8/D +14.2/E Abbott Labs ABT 103.13 129.70 118.39 1.18 33 1.80 1.5 Kimberly Clark KMB 128.02 155.45 132.87 0.69 23 4.56 3.4 WAMutInvA AWSHX 56.76 +0.88 +27.8/D +14.5/D Adv Micro Dev AMD 72.50 122.49 105.06 2.61 37 ... ... Kirby Corp KEX 35.76 70.60 52.00 3.23 55 ... ... Artisan IntlInv ARTIX 36.91 +0.05 +14.4/D +10.1/E Affirm Holdings Inc AFRM 46.50 146.90 141.19 23.34 ... ... ... Kroger Co KR 30.35 47.99 39.47 0.33 26 0.84 2.1 Calvert EqA m CSIEX 78.60 +0.60 +26.2/C +21.4/C Alaska Air Group ALK 35.06 74.25 59.80 -2.40 .. -

Fidelity® Variable Insurance Products: Disciplined Small Cap Portfolio

Quarterly Holdings Report for Fidelity® Variable Insurance Products: Disciplined Small Cap Portfolio September 30, 2020 VDSC-QTLY-1120 1.837324.114 Schedule of Investments September 30, 2020 (Unaudited) Showing Percentage of Net Assets Common Stocks – 96.3% Shares Value Shares Value COMMUNICATION SERVICES – 1.8% Shake Shack, Inc. Class A (a) (b) 2,314 $ 149,207 Diversified Telecommunication Services – 1.1% Texas Roadhouse, Inc. Class A 5,611 341,093 Bandwidth, Inc. (a) 5,099 $ 890,132 Wingstop, Inc. 2,890 394,919 Cogent Communications Group, Inc. 12,488 749,904 6,272,229 Consolidated Communications Holdings, Inc. (a) 44,196 251,475 Household Durables – 3.0% Iridium Communications, Inc. (a) 1,184 30,287 Cavco Industries, Inc. (a) 2,432 438,514 Liberty Latin America Ltd. Class C (a) (b) 14,528 118,258 Ethan Allen Interiors, Inc. 8,710 117,933 Ooma, Inc. (a) 16,451 214,686 Flexsteel Industries, Inc. 6,890 165,360 PDVWireless, Inc. (a) 2,291 74,939 Installed Building Products, Inc. (a) 1,362 138,584 2,329,681 KB Home 38,330 1,471,489 Entertainment – 0.1% La‑Z‑Boy, Inc. 20,962 663,028 Glu Mobile, Inc. (a) 23,251 178,451 M.D.C. Holdings, Inc. 17,306 815,113 Interactive Media & Services – 0.2% M/I Homes, Inc. (a) 26,746 1,231,653 Liberty TripAdvisor Holdings, Inc. (a) 17,914 30,991 Meritage Homes Corp. (a) 3,277 361,748 Yelp, Inc. (a) (b) 22,210 446,199 TopBuild Corp. (a) 369 62,985 Zedge, Inc. (a) 8,694 12,693 TRI Pointe Homes, Inc. -

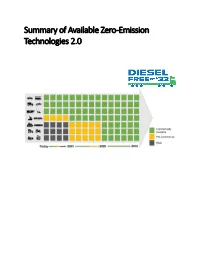

Summary of Available Zero-Emission Technologies 2.0

Summary of Available Zero-Emission Technologies 2.0 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... 2 I. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 3 II. Overview of Regulatory Framework & Incentives ................................................................................ 4 Table 1. Equipment/Vehicle Type and Applicable Regulation and Incentives...................................... 4 III. Technology Readiness Levels of Zero-Emission Vehicles and Equipment ........................................ 5 Table 2. Summary Status of Zero-Emissions Technologies in the Heavy-Duty Sector.......................... 5 Table 3. Technology Readiness Level of Buses and Considerations for Widespread Adoption ........... 6 Table 4. Technology Readiness Levels of Cargo Handling Equipment and Considerations/ Challenges .............................................................................................................................................................. 6 Table 5. Technology Readiness Levels of Construction Equipment and Considerations/ Challenges .. 8 Table 6. Technology Readiness Levels of Airport Ground Support Equipment and Considerations/ Challenges ............................................................................................................................................. 9 -

Attachment M Additional Documentation Attachment to Comment Letter 2-F2

Attachment M Additional Documentation Attachment to Comment Letter 2-F2 SanSan DiegoDiego UrbDeZineUrbDeZine Urban Design + Development + Economics + Community Click Here for Downtown San Diego’s East Village South Focus Plan – Draft HOME CALENDAR DT DEV MAP RESOURCES URB MAIN LOG IN What is a safe distance to live or work near high auto emission roads? May 28, 2015 By Bill Adams — 6 Comments A nearby roadway may be putting your household’s health at risk. The same is true of workplaces, schools, and other places where people spend signifcant time. This health risk is from the elevated auto emissions near high trafc roadways. It’s a health risk separate and in addition to the regional air pollution from auto emissions. We have come to draw a false sense of security from our collective sharing of regional air pollution and, perhaps, the belief that regulatory agencies protect us. However, research continues to show that air pollution, particularly from auto emissions, has profound efects on health. Moreover, such impacts are unequally distributed among local populations, largely based on nearness to major roadways. Discussions about whether or not to build or expand roadways are dominated by the topics of trafc congestion relief, urban planning, and greenhouse gasses. The impact of roadways on Americans’ health and morbidity is often lost in the discussions. 53,000 U.S. deaths annually Additional Documentation Attachment to Comment Letter 2-F2 are attributable to automobile emission air pollution. (Calazzo, et al., 2013) Many more are ill or incapacitated from auto emissions. Ninety percent of the cancer risk from air pollution in Southern California is attributable to auto emissions.