Ukrdyedukh Lena.Pdf (260.9Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water for Agri Sector

WATER FOR AGRI SECTOR FIRST YEAR REPORT JANUARY 22 - SEPTEMBER 30, 2015 Kyiv - Kherson This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by the SWASADRO project implemented by AMDI in Ukraine. SUSTAINABLE WATER SUPPLY FOR AGRICULTURE DEVELOPMENT ROLL-OUT (SWaSADRO) PROJECT First Year report January 22, 2015 to September 30, 2015 Cooperative Agreement No. AID-12 l-A-15-00002 October 2015 The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Sustainable Water Supply for Agriculture Development Roll-Out, FY15 Report 2 CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................ 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ 5 ENVIRONMENTAL COMPLIANCE ............................................................................................. 7 COST-SHARING ............................................................................................................................... 7 KEY MILESTONES AND MAJOR DELIVERABLES SUMMARY .......................................... 8 LIST OF MAJOR ACTIVITIES FOR THE NEXT QUARTER ................................................ 13 ATTACHMENTS ............................................................................................................................ -

Black Sea-Caspian Steppe: Natural Conditions 20 1.1 the Great Steppe

The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editors Florin Curta and Dušan Zupka volume 74 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ecee The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe By Aleksander Paroń Translated by Thomas Anessi LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Publication of the presented monograph has been subsidized by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education within the National Programme for the Development of Humanities, Modul Universalia 2.1. Research grant no. 0046/NPRH/H21/84/2017. National Programme for the Development of Humanities Cover illustration: Pechenegs slaughter prince Sviatoslav Igorevich and his “Scythians”. The Madrid manuscript of the Synopsis of Histories by John Skylitzes. Miniature 445, 175r, top. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Proofreading by Philip E. Steele The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://catalog.loc.gov/2021015848 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

Hydropolitical Vulnerability and Resilience Along International Waters” Project, Directed by Aaron T

Copyright © 2009, United Nations Environment Programme ISBN: 978-92-807-3036-4 DEWA Job No. DEW/1184/NA This publication is printed on chlorine and acid free paper from sustainable forests. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or nonprofit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. UNEP and the authors would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this report as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. United Nations Environment Programme PO Box 30552-00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 20 7624028 Fax: +254 20 7623943/44 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.unep.org United Nations Environment Programme Division of Early Warning and Assessment–North America 47914 252nd Street, EROS Data Center, Sioux Falls, SD 57198-0001 USA Tel: 1-605-594-6117 Fax: 1-605-594-6119 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.na.unep.net www.unep.org The “Hydropolitical Vulnerability and Resilience along International Waters” project, directed by Aaron T. Wolf and managed by Lynette de Silva, both of Oregon State University (OSU), USA, is a collaboration between the United Nations Environment Program – Division of Early Warning and Assessment, (UNEP-DEWA) and the Universities Partnership for Transboundary Waters. The Partnership is an international consortium of water expertise, including institutes on five continents, seeking to promote a global water governance culture that incorporates peace, environmental protection, and human security <http:// waterpartners.geo.orst.edu>. -

SGGEE Ukrainian Gazetteer 201908 Other.Xlsx

SGGEE Ukrainian gazetteer other oblasts © 2019 Dr. Frank Stewner Page 1 of 37 27.08.2021 Menno Location according to the SGGEE guideline of October 2013 North East Russian name old Name today Abai-Kutschuk (SE in Slavne), Rozdolne, Crimea, Ukraine 454300 331430 Абаи-Кучук Славне Abakly (lost), Pervomaiske, Crimea, Ukraine 454703 340700 Абаклы - Ablesch/Deutsch Ablesch (Prudy), Sovjetskyi, Crimea, Ukraine 451420 344205 Аблеш Пруди Abuslar (Vodopiyne), Saky, Crimea, Ukraine 451837 334838 Абузлар Водопійне Adamsfeld/Dsheljal (Sjeverne), Rozdolne, Crimea, Ukraine 452742 333421 Джелял Сєверне m Adelsheim (Novopetrivka), Zaporizhzhia, Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine 480506 345814 Вольный Новопетрівка Adshiaska (Rybakivka), Mykolaiv, Mykolaiv, Ukraine 463737 312229 Аджияск Рибаківка Adshiketsch (Kharytonivka), Simferopol, Crimea, Ukraine 451226 340853 Аджикечь Харитонівка m Adshi-Mambet (lost), Krasnohvardiiske, Crimea, Ukraine 452227 341100 Аджи-мамбет - Adyk (lost), Leninske, Crimea, Ukraine 451200 354715 Адык - Afrikanowka/Schweigert (N of Afrykanivka), Lozivskyi, Kharkiv, Ukraine 485410 364729 Африкановка/Швейкерт Африканівка Agaj (Chekhove), Rozdolne, Crimea, Ukraine 453306 332446 Агай Чехове Agjar-Dsheren (Kotelnykove), Krasnohvardiiske, Crimea, Ukraine 452154 340202 Агьяр-Джерень Котелникове Aitugan-Deutsch (Polohy), Krasnohvardiiske, Crimea, Ukraine 451426 342338 Айтуган Немецкий Пологи Ajkaul (lost), Pervomaiske, Crimea, Ukraine 453444 334311 Айкаул - Akkerman (Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi), Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi, Odesa, Ukraine 461117 302039 Белгород-Днестровский -

World Bank Document

ReportNo. 12238-UA Ukraine Suggested Priorities for Environmental Protection and Natural Resource Public Disclosure Authorized ltvOAnagement (In TwoVolumes) Volume I Main Report June15, 1994 NaturalRe.urce Managem-ntDivision CountryDepartment IV Europeand CentralAsia Region FOR OFFICIAL USEONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized MICROGRAPHICS Report No: 12238 UA Type: SEC Documentof theWorld Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Thisdocument has a restricteddistribution and may be usedby recipients only in theperformance of theirofficial duties. Its contentsmay not otherwise be disclosedwithout World Bankauthorization CURRENCY EQUIVALENTSAND ACRONYMS Currency unit = Karbovanets, abbrev. krb US$1 = 47,000 krb (as of June 1', 1994) Rbl = 7 krb (as of June 6, 1994) WEIGHTS AND MEASURES b Billion person- 1 person receiving 1 rem, or 10 people bcm billion n3 rem receiving 0.1 rem, or 1,000 people Bq becquerel : decay of one nucleus per second receiving 0 C I rem cm centimeter PMIO Particulate matter below 10 microns Ci curie (3.7 x 10' Bq) ppm Part per millior GJ Gigajoule (0.948 x 106 Btu rem Roentgen equivalent man: the amount of or 238.8 x 103 kcal) ionizing radiation equivalent to biological effect GW Gigawatt of one roentgen of x or gamma rays ha Hectare(s) 1 rem = I mSv kcal Kilocalorie (3.968 Btu) Sv Siwvert (mSv = millisivert) : international kg Kilogram (2.2046 Ibs) measure of the biological equivalent of an km2 Square kilometer absorbed dose of radiation. m Meter I Sv = 100 rem m3 Cubic meter (35.3147 cubic feet) -

Pottery of the Chornolis Culture in the Middle Dnieper Region

Recherches Archéologiques NS 9, 2017 (2018), 87–106 ISSN 0137 – 3285 DOI: 10.33547/RechACrac.NS9.04 Alisa Demina1 Pottery of the Chornolis culture in the middle Dnieper region Abstract: The article presents the method and results of an investigation of 885 ceramic sherds from Chor- nolis hillfort, Tyasmyn hillfort, and Kalantaiv hillfort of the Chornolis culture in the middle Dnieper region. Although highly fragmented ceramic sherds are the most frequent type of archaeological material at these sites, this is the first time their morphology and decoration have been statistically analysed. The discovered correlations among pottery parameters helped us to establish a framework for comparison of the hillforts. These findings clarified the microchronology of the sites and cultural relationships of the Chornolis culture. Keywords: Chornolis culture, fragmented ceramics, morphological analysis, hillforts, middle Dnieper region. During the late Bronze Age, significant changes took place in the territory of Eastern Europe. The powerful associations of the Noua and Sabatyniv cultures declined, and the range of the Srubna culture was reduced. At this time, Chornolis culture sites appeared along the Dnieper’s right bank, in the Dniester region, and in the basins of the Donets, Vorskla, and Orel Rivers. According to the latest research, this culture appeared not later than in the 12th century B.C. (Klochko 1998). A new stage of its development, involving massive construction of settlements in the forest-steppe of the Dnieper’s right bank, began with the arrival of the Cimmerians to the Black Sea region in the 9th century B.C. (Makhortykh 2005). The nature of this territory as a well-travelled area conditioned the significant typological variability of its material culture and the diversity of traditions. -

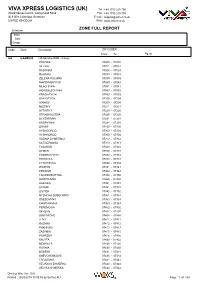

Viva Xpress Logistics (Uk)

VIVA XPRESS LOGISTICS (UK) Tel : +44 1753 210 700 World Xpress Centre, Galleymead Road Fax : +44 1753 210 709 SL3 0EN Colnbrook, Berkshire E-mail : [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Web : www.vxlnet.co.uk Selection ZONE FULL REPORT Filter : Sort : Group : Code Zone Description ZIP CODES From To Agent UA UAAOD00 UA-Ukraine AOD - 4 days POLISKE 07000 - 07004 VILCHA 07011 - 07012 RADYNKA 07024 - 07024 RAHIVKA 07033 - 07033 ZELENA POLIANA 07035 - 07035 MAKSYMOVYCHI 07040 - 07040 MLACHIVKA 07041 - 07041 HORODESCHYNA 07053 - 07053 KRASIATYCHI 07053 - 07053 SLAVUTYCH 07100 - 07199 IVANKIV 07200 - 07204 MUSIIKY 07211 - 07211 DYTIATKY 07220 - 07220 STRAKHOLISSIA 07225 - 07225 OLYZARIVKA 07231 - 07231 KROPYVNIA 07234 - 07234 ORANE 07250 - 07250 VYSHGOROD 07300 - 07304 VYSHHOROD 07300 - 07304 RUDNIA DYMERSKA 07312 - 07312 KATIUZHANKA 07313 - 07313 TOLOKUN 07323 - 07323 DYMER 07330 - 07331 KOZAROVYCHI 07332 - 07332 HLIBOVKA 07333 - 07333 LYTVYNIVKA 07334 - 07334 ZHUKYN 07341 - 07341 PIRNOVE 07342 - 07342 TARASIVSCHYNA 07350 - 07350 HAVRYLIVKA 07350 - 07350 RAKIVKA 07351 - 07351 SYNIAK 07351 - 07351 LIUTIZH 07352 - 07352 NYZHCHA DUBECHNIA 07361 - 07361 OSESCHYNA 07363 - 07363 KHOTIANIVKA 07363 - 07363 PEREMOGA 07402 - 07402 SKYBYN 07407 - 07407 DIMYTROVE 07408 - 07408 LITKY 07411 - 07411 ROZHNY 07412 - 07412 PUKHIVKA 07413 - 07413 ZAZYMIA 07415 - 07415 POHREBY 07416 - 07416 KALYTA 07420 - 07422 MOKRETS 07425 - 07425 RUDNIA 07430 - 07430 BOBRYK 07431 - 07431 SHEVCHENKOVE 07434 - 07434 TARASIVKA 07441 - 07441 VELIKAYA DYMERKA 07442 - 07442 VELYKA -

Recent Update of Mysid (Mysida) Species Composition in the Dnieper Reservoir, South-Eastern Ukraine, a Source of Several Crustacean Invaders to European Waters

BioInvasions Records (2016) Volume 5, Issue 1: 31–37 Open Access DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3391/bir.2016.5.1.06 © 2016 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2016 REABIC Research Article Recent update of mysid (Mysida) species composition in the Dnieper Reservoir, South-Eastern Ukraine, a source of several crustacean invaders to European waters 1 1 2 Кęstutis Arbačiauskas *, Eglė Šidagytė and Roman Novitskiy 1Nature Research Centre, Akademijos Str. 2, LT-08412 Vilnius, Lithuania 2Oles’ Gonchar Dnipropetrovsk National University, Faculty of Biology, Ecology and Medicine, Gagarina Str. 72, UA-49050 Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine E-mail: [email protected] (KA), [email protected] (EŠ), [email protected] (RN) *Corresponding author Received: 30 July 2015 / Accepted: 15 October 2015 / Published online: 7 November 2015 Handling editor: Vadim Panov Abstract The Dnieper Reservoir has significantly contributed as a primary source of invasive Ponto-Caspian crustaceans of Europe; therefore, the mysid populations it sustains are central to the research of invasion histories. However, the reservoir remains a waterbody susceptible to changes including the advent of new species. Mysid investigations in 2012–2014 revealed five species, Limnomysis benedeni, Paramysis lacustris, P. intermedia, P. bakuensis and Katamysis warpachowskyi, inhabiting the Dnieper Reservoir, and one species, L. benedeni, known to occur in the Dnieper- Donbass Canal. Including the previously reported Hemimysis anomala, the currently known mysid fauna of the Dnieper Reservoir consists of six species. Two of the species, P. intermedia and P. bakuensis, are reported from the reservoir for the first time. Currently, the dominant species in the shallow littoral zone are L. benedeni and P. -

Uefa Champions League

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE - 2020/21 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS NSK Olimpiyskiy - Kyiv Tuesday 1 December 2020 18.55CET (19.55 local time) FC Shakhtar Donetsk Group B - Matchday 5 Real Madrid CF Last updated 01/12/2020 00:17CET UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE OFFICIAL SPONSORS Fixtures and results 2 Legend 5 1 FC Shakhtar Donetsk - Real Madrid CF Tuesday 1 December 2020 - 18.55CET (19.55 local time) Match press kit NSK Olimpiyskiy, Kyiv Fixtures and results FC Shakhtar Donetsk Date Competition Opponent Result Goalscorers 21/08/2020 League Kolos Kovalivka (H) W 3-1 Alan Patrick 60 (P), 69, Volynets 72 (og) 20/09/2020 League FC Zorya Luhansk (A) D 2-2 Marlos 17, Kryvtsov 49 23/09/2020 League Rukh Vynnyky (A) D 1-1 Marlos 67 27/09/2020 League FC Olimpik Donetsk (H) W 2-0 Kovalenko 64, Júnior Moraes 66 04/10/2020 League FC Desna Chernihiv (A) D 2-2 Kovalenko 4, Dentinho 79 Kovalenko 4, 18, Marcos Antônio 9, 17/10/2020 League FC Lviv (H) W 5-1 Dentinho 16, Solomon 50 21/10/2020 UCL Real Madrid CF (A) W 3-2 Tetê 29, Varane 33 (og), Solomon 42 24/10/2020 League FC Vorskla Poltava (H) D 1-1 Solomon 33 27/10/2020 UCL FC Internazionale Milano (H) D 0-0 Taison 26 (P), 75, Sudakov 44, Alan 30/10/2020 League FC Mariupol (H) W 4-1 Patrick 65 (P) VfL Borussia 03/11/2020 UCL L 0-6 Mönchengladbach (H) Júnior Moraes 34, Marcos Antônio 66, 08/11/2020 League FC Dynamo Kyiv (A) W 3-0 Alan Patrick 72 21/11/2020 League FC Olexandriya (H) D 1-1 Dodô 47 VfL Borussia 25/11/2020 UCL L 0-4 Mönchengladbach (A) 28/11/2020 League Dnipro-1 (A) W 1-0 Tetê 88 01/12/2020 UCL Real Madrid -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2021

INSIDE: l Analysis: Six questions answered about the Russia-Ukraine situation – page 3 l Scholars publish book on archaeological findings in Baturyn – page 12 l Ukrainian pro sports update: soccer – page 14 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXXIX No. 15 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, APRIL 11, 2021 $2.00 Unruly Ukrainian judges evade justice Ukraine calls up military units in southern regions as Zelenskyy sanctions top smugglers as Zelenskyy urges NATO membership shared before getting married, and another lawyer were charged the following day of enriching themselves via “illicit gain.” Detectives from the National Anticorruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU) later found $3.7 million, 840,000 euros, 20,000 British pounds, and 230,000 hrv in cash during searches of their premises, in addition to antiques and documents addressed to the OASK chief justice. Ukraine’s Foreign Intelligence Service, where Mr. Zontov is employed, subsequent- ly suspended him from service during the pre-trial investigation. The two detained lawyers have stated through their lawyers that the money they had received was for “legal services.” OASK chief justice Vovk denied being National Anticorruption Bureau of Ukraine one of the intended recipients of the bribe. After searches were conducted in his cham- Hordes of cash in U.S. dollars, British Gleb Garanich, Reuters pounds, euros and hryvnias were found bers, Mr. Vovk spoke of constantly “living in in the premises of the brother of the chief an atmosphere of pressure from NABU” for Ukrainian Army personnel display U.S. Javelin antitank missiles during a military justice of the Kyiv Circuit Administra six years, which is why “we have long been parade marking Independence Day in Kyiv on August 24, 2018. -

Flint Artefacts of Northern Pontic Populations of the Early and Middle Bronze Age: 3200 – 1600 Bc

FLINT ARTEFACTS OF NORTHERN PONTIC POPULATIONS OF THE EARLY AND MIDDLE BRONZE AGE: 3200 – 1600 BC Serhiy M. Razumov ½ VOLUME 16• 2011 BALTIC-PONTIC STUDIES 61-809 Poznań (Poland) Św. Marcin 78 Tel. 618294799, Fax 618294788 E-mail: [email protected] EDITOR Aleksander Kośko EDITORIAL COMMITEE Sophia S. Berezanskaya (Kiev), Aleksandra Cofta-Broniewska (Poznań), Mikhail Charniauski (Minsk), Lucyna Domańska (Łódź), Elena G. Kalechyts (Minsk), Viktor I. Klochko (Kiev), Jan Machnik (Kraków), Vitaliy V. Otroshchenko (Kiev), Ma- rzena Szmyt (Poznań), Petro Tolochko (Kiev) SECRETARY Marzena Szmyt SECRETARY OF VOLUME Karolina Harat Danuta Żurkiewicz ADAM MICKIEWICZ UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF EASTERN STUDIES INSTITUTE OF PREHISTORY Poznań 2011 ISBN 83-86094-16-8 ISSN 1231-0344 FLINT ARTEFACTS OF NORTHERN PONTIC POPULATIONS OF THE EARLY AND MIDDLE BRONZE AGE: 3200 – 1600 BC (BASED ON BURIAL MATERIALS) Serhiy M. Razumov Translated by Inna Pidluska ½ VOLUME 16• 2011 c Copyright by BPS and Authors All rights reserved Cover Design: Eugeniusz Skorwider Linguistic consultation: Ryszard J. Reisner Printed in Poland Computer typeset by PSO Sp. z o.o. w Poznaniu Printing: Zakłady Poligraficzne TMDRUK in Poznań CONTENTS Editor’sForeword ...................................................... 5 Introduction ........................................................... 7 I. Historiography, Source Base, Research Methodology ................. 10 I.1. The Issue: Research History and Current Status . ............. 10 I.2. TheSourceBase ........................................