Gertrude Stein's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

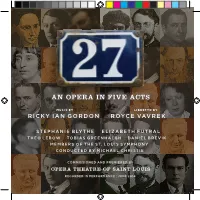

An Opera in Five Acts

AN OPERA IN FIVE ACTS MUSIC BY LIBRETTO BY RICKY IAN GORDON ROYCE VAVREK STEPHANIE BLYTHE ELIZABETH FUTRAL THEO LEBOW TOBIAS GREENHALGH DANIEL BREVIK MEMBERS OF THE ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY CONDUCTED BY MICHAEL CHRISTIE COMMISSIONED AND PREMIERED BY OPERA THEATRE OF SAINT LOUIS RECORDED IN PERFORMANCE : JUNE 2014 1 CD 1 1) PROLOGUE | ALICE KNITS THE WORLD [5:35] ACT ONE 2) SCENE 1 — 27 RUE DE FLEURUS [10:12] ALICE B. TOKLAS 3) SCENE 2 — GERTRUDE SITS FOR PABLO [5:25] AND GERTRUDE 4) SCENE 3 — BACK AT THE SALON [15:58] STEIN, 1922. ACT TWO | ZEPPELINS PHOTO BY MAN RAY. 5) SCENE 1 — CHATTER [5:21] 6) SCENE 2 — DOUGHBOY [4:13] SAN FRANCISCO ACT THREE | GÉNÉRATION PERDUE MUSEUM OF 7) INTRODUCTION; “LOST BOYS” [5:26] MODERN ART. 8) “COME MEET MAN RAY” [5:48] 9) “HOW WOULD YOU CHOOSE?” [4:59] 10) “HE’S GONE, LOVEY” [2:30] CD 2 ACT FOUR | GERTRUDE STEIN IS SAFE, SAFE 1) INTRODUCTION; “TWICE DENYING A WAR” [7:36] 2) “JURY OF MY CANVAS” [6:07] ACT FIVE | ALICE ALONE 3) INTRODUCTION; “THERE ONCE LIVED TWO WOMEN” [8:40] 4) “I’VE BEEN CALLED MANY THINGS" [8:21] 2 If a magpie in the sky on the sky can not cry if the pigeon on the grass alas can alas and to pass the pigeon on the grass alas and the magpie in the sky on the sky and to try and to try alas on the grass the pigeon on the grass and alas. They might be very well very well very ALICE B. -

A Critical Study of the Loss and Gain of the Lost Generation

Opción, Año 34, Especial No.15 (2018): 1436-1463 ISSN 1012-1587/ISSNe: 2477-9385 A Critical Study of the Loss and Gain of the Lost Generation Seyedeh Zahra Nozen1 1Department of English, Amin Police Science University [email protected] Shahriar Choubdar (MA) Malayer University, Malayer, Iran [email protected] Abstract This study aims to the evaluation of the features of the group of writers who chose Paris as their new home to produce their works and the overall dominant atmosphere in that specific time in the generation that has already experienced war through comparative research methods. As a result, writers of this group tried to find new approaches to report different contexts of modern life. As a conclusion, regardless of every member of the lost generation bohemian and wild lifestyles, the range, creativity, and influence of works produced by this community of American expatriates in Paris are remarkable. Key words: Lost Generation, World War, Disillusionment. Recibido: 04-12--2017 Aceptado: 10-03-2018 1437 Zahra Nozen and Shahriar Choubdar Opción, Año 34, Especial No.15(2018):1436-1463 Un estudio crítico de la pérdida y ganancia de la generación perdida Resumen Este estudio tiene como objetivo la evaluación de las características del grupo de escritores que eligieron París como su nuevo hogar para producir sus obras y la atmósfera dominante en ese momento específico en la generación que ya ha experimentado la guerra a través de métodos de investigación comparativos. Como resultado, los escritores de este grupo trataron de encontrar nuevos enfoques para informar diferentes contextos de la vida moderna. -

American Modernist Writers: How They Touched the Private Realm of Life Leyna Ragsdale Summer II 2006

American Modernist Writers: How They Touched the Private Realm of Life Leyna Ragsdale Summer II 2006 Introduction The issue of personal identity is one which has driven American writers to create a body of literature that not only strives to define the limitations of human capacity, but also makes a lasting contribution in redefining gender roles and stretching the bounds of freedom. A combination of several historical aspects leading up to and during the early 20th century such as Women's Suffrage and the Great War caused an uprooting of the traditional moral values held by both men and women and provoked artists to create a new American identity through modern art and literature. Gertrude Stein used her writing as a tool to express new outlooks on human sexuality and as a way to educate the public on the repression of women in order to provoke changes in society. Being a pupil of Stein's, Ernest Hemingway followed her lead in the modernist era and focused his stories on human behavior in order to educate society on the changes of gender roles and the consequences of these changes. Being a man, Hemingway focused more closely on the way that men's roles were changing while Stein focused on women's roles. However, both of these phenomenal early 20th century modernist writers made a lasting impact on post WWI America and helped to further along the inevitable change from the unrealistic Victorian idea of proper conduct and gender roles to the new modern American society. The Roles of Men and Women The United States is a country that has been reluctant to give equal rights to women and has pushed them into subservient roles. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. In his 1980 edition, Olney identified and cataloged various critical resources on autobiography, as did Leigh Gilmore fourteen years later (“Mark”). These accounts of the critical work on the genre have been formative in establishing and shaping “autobiographical studies.” 2. Foucault’s historicizing of sexuality and its discourses, in History of Sexuality, is a crucial underpinning of my work because of his emphasis on the construction of sexual paradigms as opposed to the naturalness of sexuality. 3. The collection Autobiography & Postmodernism would rectify a similar case for autobiography in studies of postmodernism; see Gilmore. 4. De Man studies the shifting nature of these “figure”s. Starobinski notes the “deviation.” 5. I agree with Gay Wachman, when she writes in her book about lesbian fiction of the 1920s that “writing, however oppositional” is “enmeshed in the dominant culture” (3); no matter how “oppositional” these writers were, they, to some extent, must rely upon the symbolic semiotics of their time. My trajectory shows the growing range in their abilities to write in another symbolic. That other symbolic has been identified as “sapphic modernism” by a number of scholars. See Laura Doan and Jane Garrity for an excellent overview of criticism (12, fn 16). 6. Andrea Harris also goes to Woolf’s exploration for the idea of “other sexes” in her excellent book on “women writers attempt[ing] to revise the prevailing system of binary gender” (xiii). Her book has provided a foundation for my own, with her argument that “gender and style form the central connection between feminism and modernity” (xv). -

Gertrude Stein*

Peter Carravetta CUNY/Graduate Center & Queens College GERTRUDE STEIN* Born: Allegheny, Pennsylvania; February 3, 1874 Died: Paris, France; July 27, 1946 Principal collections Tender Buttons, 1914; Geography and Plays, 1922; Before the Flowers of Friendship Faded Friendship Faded, 1931; Bee Time Vine and Other Pieces (1913-1927), 1953; Stanzas in Meditation and Other Poems (1929-1933), 1956. Other literary forms Most of Gertrude Stein's works did not appear until much later than the date of their completion; the plays, and theoretical writings in the following partial list bear the date of composition rather than of publication. Q.E.D. (1903); Three Lives (1905-1906); The Making of Americans (1906-1910); Matisse, Picasso and Gertrude Stein (1911-1913); Geography and Plays (1908-1920); "Composition as Explanation" (1926); Lucy Church Amiably (1927); How to Write (1927-1931); Operas and Plays (1913-1931); The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1932); Lectures in America (1934); The Geographical History of America (1935); What Are Masterpieces (1922-1936); Everybody's Autobiography (1936); Picasso (1938); The World Is Round (1938); Paris France (1939); Ida: A Novel (1940); Wars I Have Seen (1942-1944); Brewsie and Willie (1945). Much of her writing, including novelettes, shorter poems, plays, prayers, novels, and several portraits, appeared posthumously, as did the last two books of poetry noted above, in the Yale Edition of the Unpublished Writings of Gertrude Stein, in eight volumes edited by Carl Van Vechten. A few of her plays have been set to music, the operas have been performed, and the later children's books have been illustrated by various artists. -

Gertrude Stein and Alfred North Whitehead Kate Fullbrook

12 Encounters with genius: Gertrude Stein and Alfred North Whitehead Kate Fullbrook Notoriously, in her Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933), Gertrude Stein assigns to her lifelong companion the repeated comment that she has met three geniuses in her life: Stein, Picasso, and Alfred North Whitehead. This remarkable statement, which functions as one of the main structural ele- ments of the text, first appears at the end of the first chapter, in the context of Alice’s initial encounter with the woman who was to become her friend and lover. In typical Steinian fashion, everyday observations are mixed with wry, audacious gravity as Toklas first sets eyes on her future partner in the Paris house of Stein’s sister-in-law: I had come to Paris. There I went to see Mrs Stein who had in the meantime returned to Paris, and there at her house I met Gertrude Stein. I was impressed by the coral brooch she wore and by her voice. I may say that only three times in my life have I met a genius and each time a bell within me rang and I was not mistaken, and I may say in each case it was before there was any general recognition of them of the quality of genius in them. The three geniuses of whom I wish to speak are Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso and Alfred Whitehead. I have met many important people, I have met several great people but I have only known three first class geniuses and in each case on sight within me something rang. -

Gertrude Stein in Portraits: a Pose Is a Pose Is a Pose

Gertrude Stein in Portraits: A Pose Is a Pose Is a Pose A STUDY OF VISITORS TO SEEING GERTRUDE STEIN: FIVE STORIES AT THE NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY April 2012 Office of Policy and Analysis Washington, DC 20012 Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................................................................... 2 List of Figures ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Foreword .................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Methodology .............................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Quantitative Surveys ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Qualitative Interviews ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Quantitative Findings............................................................................................................................................................ -

Contexts for Reading Gertrude Stein's the Making of Americans

Contexts for Reading Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans Lucy Jane Daniel Thesis submitted to the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College^ London February 2002 ProQuest Number: U642307 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642307 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis provides a contextualizing approach to Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans (1903-1911), using her notebooks, correspondence and college compositions dating from the 1890s, as well as the more well-known Femhurst, QED, and ‘Melanctha’; the study ends in 1911. Each chapter discusses representative texts with which Stein was familiar, and which had a discernible effect on the themes and style of the novel. In view of a critical tradition which has often obscured her nineteenth-century contexts, this reading provides a clearer definition of the social and intellectual environment which shaped her literary experiment. In chapter 1 I consider the influence of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Women and Economics (1898). Stein’s college themes and the speech, ‘The Value of College Education for Women’ (1898), reveal her feelings about the possibility of female creativity. -

41141142 Gordon 27 Sample.Pdf

2 The commissioning of 27 was made possible with a leadership gift from Alison and John Ferring, and with generous support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Fred M. Saigh Endowment at Opera Theatre, the National Endowment for the Arts, and OPERA America’s Opera Fund. CONTENTS PROLOGUE: Alice Knits the World .......................................................................................... 3 ACT ONE Scene 1: 27 rue de Fleurus..................................................................................................... 23 Scene 2: Gertrude Sits for Pablo............................................................................................. 49 Scene 3: Back at the Salon ..................................................................................................... 60 ACT TWO: Zeppelins Scene 1: Chatter ..................................................................................................................... 94 Scene 2: Doughboy..............................................................................................................111 ACT THREE: Génération Perdue ...........................................................................................122 ACT FOUR: Gertrude Stein Is Safe, Safe ...............................................................................173 ACT FIVE: Alone....................................................................................................................209 SETTING Paris, 27 rue de Fleurus, the early decades of the twentieth century CAST -

Subjects, Objects, and the Fetishisms of Modernity in the Works of Gertrude Stein

Subjects, Objects, and the Fetishisms of Modernity in the Works of Gertrude Stein KATE LIVETT A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UNSW Submitted for examination August 2006 Abstract This thesis reopens the question of subject/object relations in the works of Gertrude Stein, to argue that the fetishisms theorised by Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, and later Walter Benjamin and Michael Taussig, and problematised by feminist critics such as Elizabeth Grosz, are central to the structure of those relations. My contribution to Stein scholarship is twofold, and is reflected in the division of my thesis into Part One and Part Two. Part One of this thesis establishes a model for reading the interconnections between subjects and objects in Stein’s work; it identifies a tension between two related yet different structures. The first is a fetishistic relation of subjects to objects, associated by Stein with materiality and nineteenth-century Europe, and the identity categories of the “genius” and the “collector”. The second is a “new” figuration of late modernity in which the processual and tacility are central. This latter is associated by Stein with America and the twentieth century, and was a structure that she, along with other modernist artists, was developing. Further, Part One shows how these competing structures of subject/object relations hinge on Stein’s problematic formulations of self, nation, and artistic production. Part Two uses the model established in Part One to examine the detailed playing- out of the tensions and dilemmas of subject/object relations within several major Stein texts. -

Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons As Maternal

“SOMETIME THERE IS BREATH”: GERTRUDE STEIN’S TENDER BUTTONS AS MATERNAL LEXICON BY KATHERINE MILLS WILLIAMS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS English December 2013 Winston Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Mary K. DeShazer, Ph.D., Advisor Gillian Overing, Ph.D., Chair Omaar Hena, Ph.D. Acknowledgements This thesis has been a remarkably challenging, humbling and rewarding project, and it simply would not have been possible without the help and support of Dr. DeShazer, my parents, and Sarah Schaitkin. I thank each of you. ii Table of Contents Abstract . iv Introduction . v Chapter One . 1 “The Difference between Single Lines and Broad Stomachs”: Tender Buttons and the Maternal Semiotic Chapter Two . 35 Excavating History through the Maternal Body: Theorizing Tender Buttons Conclusion . 48 Bibliography . 51 Curriculum Vitae . 54 iii Abstract A study of Gertrude Stein’s poetry collection Tender Buttons, this thesis uncovers and explores the text’s covert maternal trope. Although Stein staunchly evaded categorization as a feminist, the employment of maternal imagery and the exploration of a language predicated by the feminine space of the womb warrant a reassessment of Stein’s stance on feminism. This thesis identifies and elucidates the poetic exploration of the womb as a space containing one not yet formed, that is, the unnamed, ungendered, uninscribed in the restrictive and hegemonic yoke of culture. In this space, Stein delights in the indeterminacy of a language not yet born into the society that prescribes it to a single denotative method. -

For Immediate Release February 1, 2016

1 For Immediate Release February 1, 2016 Contact: Chris Cox, Director of Marketing and Communications Office: 412.281.0912 ext. 217 Mobile: 412.427.7088 or Email: [email protected] Pittsburgh Opera presents 27 The Pittsburgh premiere of Ricky Ian Gordon's story of Pittsburgh native Gertrude Stein What: Ricky Ian Gordon’s 27 Where: Pittsburgh Opera Headquarters, 2425 Liberty Avenue in the Strip District When: Saturday, February 20th, 2016, 8:00 p.m. Tuesday, February 23rd, 7:00 p.m. Friday, February 26th, 7:30 p.m. Sunday, February 28th, 2:00 p.m. Run Time: 95 minutes; 27 does not have an intermission Language: Sung in English with texts projected above the stage Tickets: Start at $40. Group Discounts available. Call 412-456-6666 for more information or visit pittsburghopera.org/tickets Media Media welcome to attend – Please contact [email protected] Events Photo Call - Monday, Feb. 8th Full Dress Rehearsal - Thursday, Feb. 18th Meet the Composer and Librettist – Saturday, Feb. 20th Related Brown Bag Concert - Saturday, Feb. 6th Events Opera Up Close - Sunday, Feb. 14th See pages 4-6 of this WQED Preview - Saturday, Feb. 13th & Friday, Feb. 19th release. Meet the Composer and Librettist – Saturday, Feb. 20th Meet the Artists - Tuesday, Feb. 23rd Audio Description - Tuesday, Feb. 23rd 2425 Liberty Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15222 www.pittsburghopera.org 2 Pittsburgh, PA… Pittsburgh Opera continues its 77th season with the Pittsburgh premiere of Ricky Ian Gordon’s 27. Spotlighting larger-than-life novelist, poet, playwright, and Pittsburgh native Gertrude Stein and her partner Alice B. Toklas, 27 will delight you with Ricky Ian Gordon's "tuneful score" and Royce Vavrek's "quick-witted libretto." 27 is a humorous and touching snapshot of the women's shared lives at 27 Rue de Fleurus in Paris in the early 1900s, featuring their famous salon and its visitors, including Picasso, Matisse, Hemingway, F.