Subjects, Objects, and the Fetishisms of Modernity in the Works of Gertrude Stein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If I Told Him Stein + Picasso

If I Told Him By Gertrude Stein If I told him would he like it. Would he like it if I told him. Would he like it would Napoleon would Napoleon would would he like it. If Napoleon if I told him if I told him if Napoleon. Would he like it if I told him if I told him if Napoleon. Would he like it if Napoleon if Napoleon if I told him. If I told him if Napoleon if Napoleon if I told him. If I told him would he like it would he like it if I told him. Now. Not now. And now. Now. Exactly as as kings. Feeling full for it. Exactitude as kings. So to beseech you as full as for it. Exactly or as kings. Shutters shut and open so do queens. Shutters shut and shutters and so shutters shut and shutters and so and so shutters and so shutters shut and so shutters shut and shutters and so. And so shutters shut and so and also. And also and so and so and also. Exact resemblance to exact resemblance the exact resemblance as exact resemblance, exactly as resembling, exactly resembling, exactly in resemblance exactly and resemblance. For this is so. Because. Now actively repeat at all, now actively repeat at all, now actively repeat at all. Have hold and hear, actively repeat at all. I judge judge. As a resemblance to him. Who comes first. Napoleon the first. Who comes too coming coming too, who goes there, as they go they share, who shares all, all is as all as as yet or as yet. -

“The First Futurist Manifesto Revisited,” Rett Kopi: Manifesto Issue: Dokumenterer Fremtiden (2007): 152- 56. Marjorie Perl

“The First Futurist Manifesto Revisited,” Rett Kopi: Manifesto issue: Dokumenterer Fremtiden (2007): 152- 56. Marjorie Perloff Almost a century has passed since the publication, in the Paris Figaro on 20 February 1909, of a front-page article by F. T. Marinetti called “Le Futurisme” which came to be known as the First Futurist Manifesto [Figure 1]. Famous though this manifesto quickly became, it was just as quickly reviled as a document that endorsed violence, unbridled technology, and war itself as the “hygiene of the people.” Nevertheless, the 1909 manifesto remains the touchstone of what its author called l’arte di far manifesti (“the art of making manifestos”), an art whose recipe—“violence and precision,” “the precise accusation and the well-defined insult”—became the impetus for all later manifesto-art.1 The publication of Günter Berghaus’s comprehensive new edition of Marinetti’s Critical Writings2 affords an excellent opportunity to reconsider the context as well as the rhetoric of Marinetti’s astonishing document. Consider, for starters, that the appearance of the manifesto, originally called Elettricismo or Dinamismo—Marinetti evidently hit on the more general title Futurismo while making revisions in December 2008-- was delayed by an unforeseen event that took place at the turn of 1909. On January 2, 200,000 people were killed in an earthquake in Sicily. As Berghaus tells us, Marinetti realized that this was hardly an opportune moment for startling the world with a literary manifesto, so he delayed publication until he could be sure he would get front-page coverage for his incendiary appeal to lay waste to cultural traditions and institutions. -

Post / Late? Modernity As the Context for Christian Scholarship Today,” Themelios 22.2 (January 1997): 25-38

Craig Bartholomew, “Post / Late? Modernity as the Context for Christian Scholarship Today,” Themelios 22.2 (January 1997): 25-38. Post / Late? Modernity as the Context for Christian Scholarship Today Craig Bartholomew1 [p.25] INTRODUCTION Scholarship is always historical, in the sense that it is crafted by particular humans at a particular time and place. Christian scholarship is of course no exception to this rule. Thus Christians in academia, using the insights of God’s Word, need to work as hard as anyone to understand the historical context in which they work, so that they might craft integrally Christian theory at their point in history. Once we try to think about the context in which we are doing our scholarship, the word postmodern is unavoidable. Go to any major bookshop, especially the sociology section, and you will see what I mean! Postmodern is the word in vogue to identify the context in which we in the West live and think as we head towards the end of the second millennium. In this article we shall try to unravel what ‘the postmodern turn’ involves and examine the challenge it presents for the practice of Christian scholarship at this time. THE TERM ‘POSTMODERN’ Postmodernity is an unusually slippery word, used nowadays in a bewildering variety of ways―’the adjective “postmodern” has now been applied to almost everything, from trainer shoes to the nature of our subjectivity―from “soul to soul” as the rappers might say’2. Although this fuzziness may reflect the instability of the postmodern era, it easily obscures the important issues at stake in the antithetical notions of postmodernity available today. -

An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology

An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology By C. Nadia Seremetakis An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology By C. Nadia Seremetakis This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by C. Nadia Seremetakis All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7334-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7334-5 To my students anywhere anytime CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Part I: Exploring Cultures Chapter One ................................................................................................. 4 Redefining Culture and Civilization: The Birth of Anthropology Fieldwork versus Comparative Taxonomic Methodology Diffusion or Independent Invention? Acculturation Culture as Process A Four-Field Discipline Social or Cultural Anthropology? Defining Culture Waiting for the Barbarians Part II: Writing the Other Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 30 Science/Literature Chapter Three ........................................................................................... -

Ethnographic Works by Jean Comaroff and Michael Taussig, Two Texts That Attempt to Incorporate Both an Interpretive and a World-Systems Perspective

* 21 HERMENEUTICS AND ETHNOGRAPHY: AN INTERPRETATIONOF TWOTEXTS Daniel M0 Goldstein ABSTRACT: The postmodern approach to the writing of ethnographic texts is characterized byauthorialself-reflection and a "dialogic" approach to anthropological fieldwork, techniques derived from the philosophical method of hermeneutics. But this method is problematic when confronting issues of political economy in ethnography. This paper presents an analysis of ethnographic works by Jean Comaroff and Michael Taussig, two texts that attempt to incorporate both an interpretive and a world-systems perspective. The paper examines the value of a hermeneutic method for anthropology, suggesting that while self-reflection is useful in cultural analysis, the hermeneutic method cannot be applied wholesale to the practice of anthropology. As the so-called world-system paradigm has become more central in the discipline of anthropology, certain ethnographies have begun to focus on the "colonial encounter" as an important historical process in the development of local cultures. At the same time, "post- modern" ethnography has felt the influence of the interpretive perspective, with an S orientationtowards authorial self-reflection and symbolic analysis. Two recent ethnographic texts, Jean Comaroff's Body of Power, Spirit of Resistance (1985) and Michael Taussig's The Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America (1980) study the clash of Western capitalist and traditional cultures, placing particular emphasis on the role of symbolic ritual as mediator of the cultural contradictions which this clash engenders. In this sense, both works can be regarded as attempts to unite the world-system and interpretive approaches to ethnography in a single text. However, a consideration of this attempt which focuses on the hermeneutic aspect of the two works reveals the inherent difficulty in uniting these two approaches. -

Beyond the “Postmodern University”*

Beyond the “Postmodern University”* Claire Donovan Abstract As an institution, the “postmodern university” is central to the canon of today’s research on higher education policy. Yet in this essay I argue that the postmodern university is a fiction that frames and inhibits our thinking about the future university. To understand why the postmodern university is a fiction, I first turn to grand theory and ask whether we can make sense of the notion of “post”-postmodernity. Second, I turn to the UK higher education sector and show that the postmodern university is a chimera, a modern artefact of competing instrumentalist, gothic, and postmodernist discourses. Third, I discuss competing visions of the future university and find that the progressive (yet modernist) agendas that re-imagine the public value of knowledge production, transmission, and contestation, are those that can move us beyond the palliative and panacea of the postmodern university. * Health Economics Research Group, Brunel University, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UK. Email: [email protected]. 1 In this essay I investigate the idea of the postmodern university, an institution that is central to research on, and debate about, higher education policy.1 I contend that the postmodern university does not actually exist, yet this fiction casts a shadow over discussions of higher education policy that inhibits more lateral and creative thinking about the future university. In order to properly investigate the concept of the postmodern, it is first necessary to explain the difference between postmodernism and postmodernity. I then ask if we can make sense of being “beyond” postmodernity to prove that postmodernity has never, in fact, existed. -

The Licit and the Illicit in Archaeological and Heritage Discourses

CHALLENGING THE DICHOTOMY EDIT ED BY LES FIELD CRISTÓBAL GNeccO JOE WATKINS CHALLENGING THE DICHOTOMY • The Licit and the Illicit in Archaeological and Heritage Discourses TUCSON The University of Arizona Press www.uapress.arizona.edu © 2016 by The Arizona Board of Regents Open-access edition published 2020 ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-3130-1 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-4169-0 (open-access e-book) The text of this book is licensed under the Creative Commons Atrribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivsatives 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Cover designed by Leigh McDonald Publication of this book is made possible in part by the Wenner-Gren Foundation. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Field, Les W., editor. | Gnecco, Cristóbal, editor. | Watkins, Joe, 1951– editor. Title: Challenging the dichotomy : the licit and the illicit in archaeological and heritage discourses / edited by Les Field, Cristóbal Gnecco, and Joe Watkins. Description: Tucson : The University of Arizona Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016007488 | ISBN 9780816531301 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Archaeology. | Archaeology and state. | Cultural property—Protection. Classification: LCC CC65 .C47 2016 | DDC 930.1—dc23 LC record available at https:// lccn.loc.gov/2016007488 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. -

The Radical Ekphrasis of Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons Georgia Googer University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2018 The Radical Ekphrasis Of Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons Georgia Googer University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Recommended Citation Googer, Georgia, "The Radical Ekphrasis Of Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons" (2018). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 889. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/889 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RADICAL EKPHRASIS OF GERTRUDE STEIN’S TENDER BUTTONS A Thesis Presented by Georgia Googer to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in English May, 2018 Defense Date: March 21, 2018 Thesis Examination Committee: Mary Louise Kete, Ph.D., Advisor Melanie S. Gustafson, Ph.D., Chairperson Eric R. Lindstrom, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College ABSTRACT This thesis offers a reading of Gertrude Stein’s 1914 prose poetry collection, Tender Buttons, as a radical experiment in ekphrasis. A project that began with an examination of the avant-garde imagism movement in the early twentieth century, this thesis notes how Stein’s work differs from her Imagist contemporaries through an exploration of material spaces and objects as immersive sensory experiences. This thesis draws on late twentieth century attempts to understand and define ekphrastic poetry before turning to Tender Buttons. -

![Ida, a [Performative] Novel and the Construction of Id/Entity](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4638/ida-a-performative-novel-and-the-construction-of-id-entity-1024638.webp)

Ida, a [Performative] Novel and the Construction of Id/Entity

Wesleyan University The Honors College Ida, A [Performative] Novel and the Construction of Id/Entity by Katherine Malczewski Class of 2015 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in Theater Middletown, Connecticut April, 2015 Malczewski 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………..2 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………3 Stein’s Theoretical Framework………………………………………………………..4 Stein’s Writing Process and Techniques……………………………………………..12 Ida, A Novel: Context and Textual Analysis………………………………...……….17 Stein’s Theater, the Aesthetics of the Performative, and the Actor’s Work in Ida…………………………………………………25 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………...40 Notes…………………………………………………………………………………41 Appendix: Adaptation of Ida, A Novel……………………………....………………44 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………….56 Malczewski 2 Acknowledgments Many thanks to all the people who have supported me throughout this process: To my director, advisor, and mentor, Cláudia Tatinge Nascimento. You ignited my passion for both the works of Gertrude Stein and “weird” theater during my freshman year by casting me in Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights. Since then, you have offered me with invaluable guidance and insight, teaching me that the process is just as important as the performance. I am eternally grateful for all the time and energy you have dedicated to this project. To the Wesleyan Theater Department, for guiding me throughout my four years at Wesleyan, encouraging me to embrace collaboration, and making the performance of Ida, A Novel possible. Special thanks to Marcela Oteíza and Leslie Weinberg, for your help and advice during the process of Ida. To my English advisors, Courtney Weiss Smith and Rachel Ellis Neyra, for challenging me to think critically and making me a better writer in the process. -

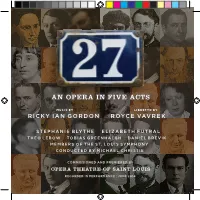

An Opera in Five Acts

AN OPERA IN FIVE ACTS MUSIC BY LIBRETTO BY RICKY IAN GORDON ROYCE VAVREK STEPHANIE BLYTHE ELIZABETH FUTRAL THEO LEBOW TOBIAS GREENHALGH DANIEL BREVIK MEMBERS OF THE ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY CONDUCTED BY MICHAEL CHRISTIE COMMISSIONED AND PREMIERED BY OPERA THEATRE OF SAINT LOUIS RECORDED IN PERFORMANCE : JUNE 2014 1 CD 1 1) PROLOGUE | ALICE KNITS THE WORLD [5:35] ACT ONE 2) SCENE 1 — 27 RUE DE FLEURUS [10:12] ALICE B. TOKLAS 3) SCENE 2 — GERTRUDE SITS FOR PABLO [5:25] AND GERTRUDE 4) SCENE 3 — BACK AT THE SALON [15:58] STEIN, 1922. ACT TWO | ZEPPELINS PHOTO BY MAN RAY. 5) SCENE 1 — CHATTER [5:21] 6) SCENE 2 — DOUGHBOY [4:13] SAN FRANCISCO ACT THREE | GÉNÉRATION PERDUE MUSEUM OF 7) INTRODUCTION; “LOST BOYS” [5:26] MODERN ART. 8) “COME MEET MAN RAY” [5:48] 9) “HOW WOULD YOU CHOOSE?” [4:59] 10) “HE’S GONE, LOVEY” [2:30] CD 2 ACT FOUR | GERTRUDE STEIN IS SAFE, SAFE 1) INTRODUCTION; “TWICE DENYING A WAR” [7:36] 2) “JURY OF MY CANVAS” [6:07] ACT FIVE | ALICE ALONE 3) INTRODUCTION; “THERE ONCE LIVED TWO WOMEN” [8:40] 4) “I’VE BEEN CALLED MANY THINGS" [8:21] 2 If a magpie in the sky on the sky can not cry if the pigeon on the grass alas can alas and to pass the pigeon on the grass alas and the magpie in the sky on the sky and to try and to try alas on the grass the pigeon on the grass and alas. They might be very well very well very ALICE B. -

A Critical Study of the Loss and Gain of the Lost Generation

Opción, Año 34, Especial No.15 (2018): 1436-1463 ISSN 1012-1587/ISSNe: 2477-9385 A Critical Study of the Loss and Gain of the Lost Generation Seyedeh Zahra Nozen1 1Department of English, Amin Police Science University [email protected] Shahriar Choubdar (MA) Malayer University, Malayer, Iran [email protected] Abstract This study aims to the evaluation of the features of the group of writers who chose Paris as their new home to produce their works and the overall dominant atmosphere in that specific time in the generation that has already experienced war through comparative research methods. As a result, writers of this group tried to find new approaches to report different contexts of modern life. As a conclusion, regardless of every member of the lost generation bohemian and wild lifestyles, the range, creativity, and influence of works produced by this community of American expatriates in Paris are remarkable. Key words: Lost Generation, World War, Disillusionment. Recibido: 04-12--2017 Aceptado: 10-03-2018 1437 Zahra Nozen and Shahriar Choubdar Opción, Año 34, Especial No.15(2018):1436-1463 Un estudio crítico de la pérdida y ganancia de la generación perdida Resumen Este estudio tiene como objetivo la evaluación de las características del grupo de escritores que eligieron París como su nuevo hogar para producir sus obras y la atmósfera dominante en ese momento específico en la generación que ya ha experimentado la guerra a través de métodos de investigación comparativos. Como resultado, los escritores de este grupo trataron de encontrar nuevos enfoques para informar diferentes contextos de la vida moderna. -

University of Alberta

University of Alberta Gertrude Stein’s Cubist Brain Maps by Lorelee Kim Kippen A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Comparative Literature ©Lorelee Kim Kippen Fall 2009 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-53987-3 Our file Notre référence ISBN:978-0-494-53987-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats.