Gertrude Stein Addresses the Five Hundred Robert M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gertrude Stein and Her Audience: Small Presses, Little Magazines, and the Reconfiguration of Modern Authorship

GERTRUDE STEIN AND HER AUDIENCE: SMALL PRESSES, LITTLE MAGAZINES, AND THE RECONFIGURATION OF MODERN AUTHORSHIP KALI MCKAY BACHELOR OF ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF LETHBRIDGE, 2006 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of English University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Kali McKay, 2010 Abstract: This thesis examines the publishing career of Gertrude Stein, an American expatriate writer whose experimental style left her largely unpublished throughout much of her career. Stein’s various attempts at dissemination illustrate the importance she placed on being paid for her work and highlight the paradoxical relationship between Stein and her audience. This study shows that there was an intimate relationship between literary modernism and mainstream culture as demonstrated by Stein’s need for the public recognition and financial gains by which success had long been measured. Stein’s attempt to embrace the definition of the author as a professional who earned a living through writing is indicative of the developments in art throughout the first decades of the twentieth century, and it problematizes modern authorship by re- emphasizing the importance of commercial success to artists previously believed to have been indifferent to the reaction of their audience. iii Table of Contents Title Page ………………………………………………………………………………. i Signature Page ………………………………………………………………………… ii Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………….. iii Table of Contents …………………………………………………………………….. iv Chapter One …………………………………………………………………………..... 1 Chapter Two ………………………………………………………………………….. 26 Chapter Three ………………………………………………………………………… 47 Chapter Four .………………………………………………………………………... 66 Works Cited .………………………………………………………………………….. 86 iv Chapter One Hostile readers of Gertrude Stein’s work have frequently accused her of egotism, claiming that she was a talentless narcissist who imposed her maunderings on the public with an undeserved sense of self-satisfaction. -

![Ida, a [Performative] Novel and the Construction of Id/Entity](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4638/ida-a-performative-novel-and-the-construction-of-id-entity-1024638.webp)

Ida, a [Performative] Novel and the Construction of Id/Entity

Wesleyan University The Honors College Ida, A [Performative] Novel and the Construction of Id/Entity by Katherine Malczewski Class of 2015 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in Theater Middletown, Connecticut April, 2015 Malczewski 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………..2 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………3 Stein’s Theoretical Framework………………………………………………………..4 Stein’s Writing Process and Techniques……………………………………………..12 Ida, A Novel: Context and Textual Analysis………………………………...……….17 Stein’s Theater, the Aesthetics of the Performative, and the Actor’s Work in Ida…………………………………………………25 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………...40 Notes…………………………………………………………………………………41 Appendix: Adaptation of Ida, A Novel……………………………....………………44 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………….56 Malczewski 2 Acknowledgments Many thanks to all the people who have supported me throughout this process: To my director, advisor, and mentor, Cláudia Tatinge Nascimento. You ignited my passion for both the works of Gertrude Stein and “weird” theater during my freshman year by casting me in Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights. Since then, you have offered me with invaluable guidance and insight, teaching me that the process is just as important as the performance. I am eternally grateful for all the time and energy you have dedicated to this project. To the Wesleyan Theater Department, for guiding me throughout my four years at Wesleyan, encouraging me to embrace collaboration, and making the performance of Ida, A Novel possible. Special thanks to Marcela Oteíza and Leslie Weinberg, for your help and advice during the process of Ida. To my English advisors, Courtney Weiss Smith and Rachel Ellis Neyra, for challenging me to think critically and making me a better writer in the process. -

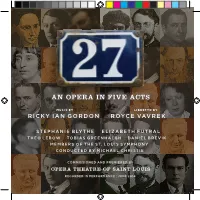

An Opera in Five Acts

AN OPERA IN FIVE ACTS MUSIC BY LIBRETTO BY RICKY IAN GORDON ROYCE VAVREK STEPHANIE BLYTHE ELIZABETH FUTRAL THEO LEBOW TOBIAS GREENHALGH DANIEL BREVIK MEMBERS OF THE ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY CONDUCTED BY MICHAEL CHRISTIE COMMISSIONED AND PREMIERED BY OPERA THEATRE OF SAINT LOUIS RECORDED IN PERFORMANCE : JUNE 2014 1 CD 1 1) PROLOGUE | ALICE KNITS THE WORLD [5:35] ACT ONE 2) SCENE 1 — 27 RUE DE FLEURUS [10:12] ALICE B. TOKLAS 3) SCENE 2 — GERTRUDE SITS FOR PABLO [5:25] AND GERTRUDE 4) SCENE 3 — BACK AT THE SALON [15:58] STEIN, 1922. ACT TWO | ZEPPELINS PHOTO BY MAN RAY. 5) SCENE 1 — CHATTER [5:21] 6) SCENE 2 — DOUGHBOY [4:13] SAN FRANCISCO ACT THREE | GÉNÉRATION PERDUE MUSEUM OF 7) INTRODUCTION; “LOST BOYS” [5:26] MODERN ART. 8) “COME MEET MAN RAY” [5:48] 9) “HOW WOULD YOU CHOOSE?” [4:59] 10) “HE’S GONE, LOVEY” [2:30] CD 2 ACT FOUR | GERTRUDE STEIN IS SAFE, SAFE 1) INTRODUCTION; “TWICE DENYING A WAR” [7:36] 2) “JURY OF MY CANVAS” [6:07] ACT FIVE | ALICE ALONE 3) INTRODUCTION; “THERE ONCE LIVED TWO WOMEN” [8:40] 4) “I’VE BEEN CALLED MANY THINGS" [8:21] 2 If a magpie in the sky on the sky can not cry if the pigeon on the grass alas can alas and to pass the pigeon on the grass alas and the magpie in the sky on the sky and to try and to try alas on the grass the pigeon on the grass and alas. They might be very well very well very ALICE B. -

A Critical Study of the Loss and Gain of the Lost Generation

Opción, Año 34, Especial No.15 (2018): 1436-1463 ISSN 1012-1587/ISSNe: 2477-9385 A Critical Study of the Loss and Gain of the Lost Generation Seyedeh Zahra Nozen1 1Department of English, Amin Police Science University [email protected] Shahriar Choubdar (MA) Malayer University, Malayer, Iran [email protected] Abstract This study aims to the evaluation of the features of the group of writers who chose Paris as their new home to produce their works and the overall dominant atmosphere in that specific time in the generation that has already experienced war through comparative research methods. As a result, writers of this group tried to find new approaches to report different contexts of modern life. As a conclusion, regardless of every member of the lost generation bohemian and wild lifestyles, the range, creativity, and influence of works produced by this community of American expatriates in Paris are remarkable. Key words: Lost Generation, World War, Disillusionment. Recibido: 04-12--2017 Aceptado: 10-03-2018 1437 Zahra Nozen and Shahriar Choubdar Opción, Año 34, Especial No.15(2018):1436-1463 Un estudio crítico de la pérdida y ganancia de la generación perdida Resumen Este estudio tiene como objetivo la evaluación de las características del grupo de escritores que eligieron París como su nuevo hogar para producir sus obras y la atmósfera dominante en ese momento específico en la generación que ya ha experimentado la guerra a través de métodos de investigación comparativos. Como resultado, los escritores de este grupo trataron de encontrar nuevos enfoques para informar diferentes contextos de la vida moderna. -

Representation, Re-Presentation, and Repetition of the Past in Gertrude

Representation, Re-presentation, and Repetition of the Past in Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans by Alexandria Sanborn Representation, Re-presentation, and Repetition of the Past in Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans by Alexandria Sanborn A thesis presented for the B. A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Spring 2011 © March 2011, Alexandria Mary Sanborn This thesis is dedicated my father. Even as he remains my most exasperating critic, his opinion has always mattered most to me. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my adviser, Andrea Zemgulys for her help and guidance throughout this project. At the start of this year, I was unsure about what I wanted to say about Stein, and our initial conversation guided me back to ideas I needed to continue pursuing. As I near the finish line, I look back at my initial drafts and am flooded with gratitude for her ability to tactfully identify the strengths and weaknesses of my argument while parsing through my incoherent prose. She was always open and responsive to my ideas and encouraged me to embrace them as my own, which gave me the confidence to enter a critical conversation that seemed to resist my reading of Stein. Next, I thank Cathy Sanok and Honors English cohort who have provided valuable feedback about my writing throughout the drafting process and were able to truly understand and commiserate with me during the more stressful periods of writing. Through the financial support of the Wagner Bursary, I had the opportunity to visit the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University to read Stein’s notebooks and early drafts of The Making of Americans. -

Reading Cruft: a Cognitive Approach to the Mega-Novel

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 Reading Cruft: A Cognitive Approach to the Mega-Novel David J. Letzler Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/247 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] READING CRUFT A COGNITIVE APPROACH TO THE MEGA-NOVEL by DAVID LETZLER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 DAVID JOSEPH LETZLER All rights reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Gerhard Joseph _______________________ ___________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Mario DiGangi _______________________ ___________________________________________ Date Executive Officer Gerhard Joseph Nico Israel Mario DiGangi Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract READING CRUFT: A COGNITIVE APPROACH TO THE MEGA-NOVEL by David Letzler Adviser: Gerhard Joseph Reading Cruft offers a new critical model for examining a genre vital to modern literature, the mega-novel. Building on theoretical work in both cognitive narratology and cognitive poetics, it argues that the mega-novel is primarily characterized by its inclusion of a substantial amount of pointless text (“cruft”), which it uses to challenge its readers’ abilities to modulate their attention and rapidly shift their modes of text processing. -

American Modernist Writers: How They Touched the Private Realm of Life Leyna Ragsdale Summer II 2006

American Modernist Writers: How They Touched the Private Realm of Life Leyna Ragsdale Summer II 2006 Introduction The issue of personal identity is one which has driven American writers to create a body of literature that not only strives to define the limitations of human capacity, but also makes a lasting contribution in redefining gender roles and stretching the bounds of freedom. A combination of several historical aspects leading up to and during the early 20th century such as Women's Suffrage and the Great War caused an uprooting of the traditional moral values held by both men and women and provoked artists to create a new American identity through modern art and literature. Gertrude Stein used her writing as a tool to express new outlooks on human sexuality and as a way to educate the public on the repression of women in order to provoke changes in society. Being a pupil of Stein's, Ernest Hemingway followed her lead in the modernist era and focused his stories on human behavior in order to educate society on the changes of gender roles and the consequences of these changes. Being a man, Hemingway focused more closely on the way that men's roles were changing while Stein focused on women's roles. However, both of these phenomenal early 20th century modernist writers made a lasting impact on post WWI America and helped to further along the inevitable change from the unrealistic Victorian idea of proper conduct and gender roles to the new modern American society. The Roles of Men and Women The United States is a country that has been reluctant to give equal rights to women and has pushed them into subservient roles. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. In his 1980 edition, Olney identified and cataloged various critical resources on autobiography, as did Leigh Gilmore fourteen years later (“Mark”). These accounts of the critical work on the genre have been formative in establishing and shaping “autobiographical studies.” 2. Foucault’s historicizing of sexuality and its discourses, in History of Sexuality, is a crucial underpinning of my work because of his emphasis on the construction of sexual paradigms as opposed to the naturalness of sexuality. 3. The collection Autobiography & Postmodernism would rectify a similar case for autobiography in studies of postmodernism; see Gilmore. 4. De Man studies the shifting nature of these “figure”s. Starobinski notes the “deviation.” 5. I agree with Gay Wachman, when she writes in her book about lesbian fiction of the 1920s that “writing, however oppositional” is “enmeshed in the dominant culture” (3); no matter how “oppositional” these writers were, they, to some extent, must rely upon the symbolic semiotics of their time. My trajectory shows the growing range in their abilities to write in another symbolic. That other symbolic has been identified as “sapphic modernism” by a number of scholars. See Laura Doan and Jane Garrity for an excellent overview of criticism (12, fn 16). 6. Andrea Harris also goes to Woolf’s exploration for the idea of “other sexes” in her excellent book on “women writers attempt[ing] to revise the prevailing system of binary gender” (xiii). Her book has provided a foundation for my own, with her argument that “gender and style form the central connection between feminism and modernity” (xv). -

Everybody's Story: Gertrude Stein's Career As a Nexus

EVERYBODY’S STORY: GERTRUDE STEIN’S CAREER AS A NEXUS CONNECTING WRITERS AND PAINTERS IN BOHEMIAN PARIS By Elizabeth Frances Milam A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally Barksdale Honors College Oxford, May 2017 Approved by: _______________________________________ Advisor: Professor Elizabeth Spencer _______________________________________ Reader: Professor Matt Bondurant ______________________________________ Reader: Professor John Samonds i ©2017 Elizabeth Frances Milam ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ELIZABETH FRANCES MILAM: EVERYBODY’S STORY: GERTRUDE STEIN’S CAREER AS A NEXUS CONNECTING WRITERS AND PAINTERS IN BOHEMIAN PARIS Advisor: Elizabeth Spencer My thesis seeks to question how the combination of Gertrude Stein, Paris, and the time period before, during, and after The Great War conflated to create the Lost Generation and affected the work of Sherwood Anderson and Ernest Hemingway. Five different sections focus on: the background of Stein and how her understanding of expression came into existence, Paris and the unique environment it provided for experimentation at the beginning of the twentieth century (and how that compared to the environment found in America), Modernism existing in Paris prior to World War One, the mass culture of militarization in World War One and the effect on the subjective perspective, and post-war Paris, Stein, and the Lost Generation. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………v-vi CHAPTER ONE: STEIN’S FORMATIVE YEARS…………………………..vii-xiv CHAPTER TWO: EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY PARIS……..………...xv-xxvi CHAPTER THREE: PREWAR MODERNISM.........………………………...xxvii-xl CHAPTER FOUR: WORLD WAR ONE…….......…………..…………..……...xl-liii CHAPTER FIVE: POST WAR PARIS, STEIN, AND MODERNISM ……liii-lxxiv CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………....lxxv-lxxvii BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………………………….lxxviii-lxxxiii iv INTRODUCTION: The destruction caused by The Great War left behind a gaping chasm between the pre-war worldview and the dark reality left after the war. -

Gertrude Stein's

GERTRUDE STEIN’S WAR by Anne-Marie Levine Contemporary French Civilization: “Culture and Daily Life in Occupied France.” Summer/Fall 1999, Volume XXIII, No. 2, pp 223-243. I was delighted, on being asked to participate in this conference, to realize that two of the writers who mean the most to me, Gertrude Stein and Samuel Beckett, spent the war years in France. Doubly delighted to know that they lived in rural France, also very close to my heart, since I spent some time studying village life in the French Pays Basque. Gertrude Stein, as you may know, was an American writer and “personnage” who had lived in Paris since the early l900s and had summered near Belley in Eastern France since about l924. She lived in Paris first with her brother Leo, and from l908 or so with her lifelong companion, Alice B. Toklas (the B stands for Babette) who was also American. They were, in fact, Californians. Stein was an experimental writer and a wholly original writer and not the least because she was preoccupied in her writing with history, and with the history of daily life as opposed to the history of events. You may know that she and her brother were at the center of the world of avant-garde painting as well as writing, from the early l900s on—they were among the first to buy the work of Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso, and Gauguin, and they bought Degas, Delacroix, Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec and many others as well. Stein said of Cézanne that he “conceived the idea that in composition one thing was as important as another thing, each part is as important as the whole” and that impressed her so much she began to write in a certain way—a book called Three Lives—and that was in l909.1 This point of view is central to her portrayal of daily life and perhaps to any successful joining of art and daily life. -

Gertrude Stein*

Peter Carravetta CUNY/Graduate Center & Queens College GERTRUDE STEIN* Born: Allegheny, Pennsylvania; February 3, 1874 Died: Paris, France; July 27, 1946 Principal collections Tender Buttons, 1914; Geography and Plays, 1922; Before the Flowers of Friendship Faded Friendship Faded, 1931; Bee Time Vine and Other Pieces (1913-1927), 1953; Stanzas in Meditation and Other Poems (1929-1933), 1956. Other literary forms Most of Gertrude Stein's works did not appear until much later than the date of their completion; the plays, and theoretical writings in the following partial list bear the date of composition rather than of publication. Q.E.D. (1903); Three Lives (1905-1906); The Making of Americans (1906-1910); Matisse, Picasso and Gertrude Stein (1911-1913); Geography and Plays (1908-1920); "Composition as Explanation" (1926); Lucy Church Amiably (1927); How to Write (1927-1931); Operas and Plays (1913-1931); The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1932); Lectures in America (1934); The Geographical History of America (1935); What Are Masterpieces (1922-1936); Everybody's Autobiography (1936); Picasso (1938); The World Is Round (1938); Paris France (1939); Ida: A Novel (1940); Wars I Have Seen (1942-1944); Brewsie and Willie (1945). Much of her writing, including novelettes, shorter poems, plays, prayers, novels, and several portraits, appeared posthumously, as did the last two books of poetry noted above, in the Yale Edition of the Unpublished Writings of Gertrude Stein, in eight volumes edited by Carl Van Vechten. A few of her plays have been set to music, the operas have been performed, and the later children's books have been illustrated by various artists. -

Gertrude Stein and Alfred North Whitehead Kate Fullbrook

12 Encounters with genius: Gertrude Stein and Alfred North Whitehead Kate Fullbrook Notoriously, in her Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933), Gertrude Stein assigns to her lifelong companion the repeated comment that she has met three geniuses in her life: Stein, Picasso, and Alfred North Whitehead. This remarkable statement, which functions as one of the main structural ele- ments of the text, first appears at the end of the first chapter, in the context of Alice’s initial encounter with the woman who was to become her friend and lover. In typical Steinian fashion, everyday observations are mixed with wry, audacious gravity as Toklas first sets eyes on her future partner in the Paris house of Stein’s sister-in-law: I had come to Paris. There I went to see Mrs Stein who had in the meantime returned to Paris, and there at her house I met Gertrude Stein. I was impressed by the coral brooch she wore and by her voice. I may say that only three times in my life have I met a genius and each time a bell within me rang and I was not mistaken, and I may say in each case it was before there was any general recognition of them of the quality of genius in them. The three geniuses of whom I wish to speak are Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso and Alfred Whitehead. I have met many important people, I have met several great people but I have only known three first class geniuses and in each case on sight within me something rang.