Baltimore Blues: Gertrude Stein at Johns Hopkins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If I Told Him Stein + Picasso

If I Told Him By Gertrude Stein If I told him would he like it. Would he like it if I told him. Would he like it would Napoleon would Napoleon would would he like it. If Napoleon if I told him if I told him if Napoleon. Would he like it if I told him if I told him if Napoleon. Would he like it if Napoleon if Napoleon if I told him. If I told him if Napoleon if Napoleon if I told him. If I told him would he like it would he like it if I told him. Now. Not now. And now. Now. Exactly as as kings. Feeling full for it. Exactitude as kings. So to beseech you as full as for it. Exactly or as kings. Shutters shut and open so do queens. Shutters shut and shutters and so shutters shut and shutters and so and so shutters and so shutters shut and so shutters shut and shutters and so. And so shutters shut and so and also. And also and so and so and also. Exact resemblance to exact resemblance the exact resemblance as exact resemblance, exactly as resembling, exactly resembling, exactly in resemblance exactly and resemblance. For this is so. Because. Now actively repeat at all, now actively repeat at all, now actively repeat at all. Have hold and hear, actively repeat at all. I judge judge. As a resemblance to him. Who comes first. Napoleon the first. Who comes too coming coming too, who goes there, as they go they share, who shares all, all is as all as as yet or as yet. -

“The First Futurist Manifesto Revisited,” Rett Kopi: Manifesto Issue: Dokumenterer Fremtiden (2007): 152- 56. Marjorie Perl

“The First Futurist Manifesto Revisited,” Rett Kopi: Manifesto issue: Dokumenterer Fremtiden (2007): 152- 56. Marjorie Perloff Almost a century has passed since the publication, in the Paris Figaro on 20 February 1909, of a front-page article by F. T. Marinetti called “Le Futurisme” which came to be known as the First Futurist Manifesto [Figure 1]. Famous though this manifesto quickly became, it was just as quickly reviled as a document that endorsed violence, unbridled technology, and war itself as the “hygiene of the people.” Nevertheless, the 1909 manifesto remains the touchstone of what its author called l’arte di far manifesti (“the art of making manifestos”), an art whose recipe—“violence and precision,” “the precise accusation and the well-defined insult”—became the impetus for all later manifesto-art.1 The publication of Günter Berghaus’s comprehensive new edition of Marinetti’s Critical Writings2 affords an excellent opportunity to reconsider the context as well as the rhetoric of Marinetti’s astonishing document. Consider, for starters, that the appearance of the manifesto, originally called Elettricismo or Dinamismo—Marinetti evidently hit on the more general title Futurismo while making revisions in December 2008-- was delayed by an unforeseen event that took place at the turn of 1909. On January 2, 200,000 people were killed in an earthquake in Sicily. As Berghaus tells us, Marinetti realized that this was hardly an opportune moment for startling the world with a literary manifesto, so he delayed publication until he could be sure he would get front-page coverage for his incendiary appeal to lay waste to cultural traditions and institutions. -

Gertrude Stein and Her Audience: Small Presses, Little Magazines, and the Reconfiguration of Modern Authorship

GERTRUDE STEIN AND HER AUDIENCE: SMALL PRESSES, LITTLE MAGAZINES, AND THE RECONFIGURATION OF MODERN AUTHORSHIP KALI MCKAY BACHELOR OF ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF LETHBRIDGE, 2006 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of English University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Kali McKay, 2010 Abstract: This thesis examines the publishing career of Gertrude Stein, an American expatriate writer whose experimental style left her largely unpublished throughout much of her career. Stein’s various attempts at dissemination illustrate the importance she placed on being paid for her work and highlight the paradoxical relationship between Stein and her audience. This study shows that there was an intimate relationship between literary modernism and mainstream culture as demonstrated by Stein’s need for the public recognition and financial gains by which success had long been measured. Stein’s attempt to embrace the definition of the author as a professional who earned a living through writing is indicative of the developments in art throughout the first decades of the twentieth century, and it problematizes modern authorship by re- emphasizing the importance of commercial success to artists previously believed to have been indifferent to the reaction of their audience. iii Table of Contents Title Page ………………………………………………………………………………. i Signature Page ………………………………………………………………………… ii Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………….. iii Table of Contents …………………………………………………………………….. iv Chapter One …………………………………………………………………………..... 1 Chapter Two ………………………………………………………………………….. 26 Chapter Three ………………………………………………………………………… 47 Chapter Four .………………………………………………………………………... 66 Works Cited .………………………………………………………………………….. 86 iv Chapter One Hostile readers of Gertrude Stein’s work have frequently accused her of egotism, claiming that she was a talentless narcissist who imposed her maunderings on the public with an undeserved sense of self-satisfaction. -

Vol. 23, No. 8 August 2019 You Can’T Buy It

ABSOLUTELY FREE Vol. 23, No. 8 August 2019 You Can’t Buy It As Above, So Below Artwork is by Diane Nations and is part of her exhibit Under the Influence of Jung on view at Artworks Gallery in Winston-Salem, North Carolina through August 31, 2019. See the article on Page 28. ARTICLE INDEX Advertising Directory This index has active links, just click on the Page number and it will take you to that page. Listed in order in which they appear in the paper. Page 1 - Cover - Artworks Gallery (Winston-Salem) - Diane Nations Page 3 - Ella Walton Richardson Fine Art Page 2 - Article Index, Advertising Directory, Contact Info, Links to blogs, and Carolina Arts site Page 5 - Wells Gallery at the Sanctuary & Halsey MCallum Studio Page 4 - Redux Contemporary Art Center & Charleston Artist Guild Page 6 - Thomas Dixon for Mayor & Jesse Williams District 6 Page 5 - Charleston Museum & Robert Lange Studios Page 7 - Emerge SC, Helena Fox Fine Art, Corrigan Gallery, Halsey-McCallum Studio, Page 6 - Robert Lange Studios cont., Ella Walton Richardson Fine Art & Rhett Thurman, Anglin Smith Fine Art, Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art, Lowcountry Artists Gallery The Wells Gallery at the Sanctuary & Saul Alexander Foundation Gallery Page 9 - Lowcountry Artists Gallery cont. & Halsey Institute / College of Charleston Page 8 - Halsey Institute / College of Charleston Page 10 - Halsey Institute / College of Charleston & Art League of Hilton Head Page 9 - Whimsy Joy Page 11 - Art League of Hilton Head cont. & Society of Bluffton Artists Page 10 - Halsey Institute -

Bma Presents Matisse Prints and Drawings

Media Contacts: Anne Brown Jessica Novak Sarah Pedroni 443-573-1870 BMA PRESENTS MATISSE PRINTS AND DRAWINGS New Arrivals exhibition recognizes BMA’s continued relationship with the Matisse family BALTIMORE, MD (December 3, 2015)—The Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) presents a sublime exhibition of works by Henri Matisse, one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. On view December 9, 2015-July 3, 2016, New Arrivals: Matisse Prints & Drawings features approximately 40 recently acquired prints and drawings, most bestowed to the BMA by the collection of Matisse’s daughter, Marguerite Matisse Duthuit, and The Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation in New York. The exhibition—one of nine celebrating the museum’s enormously successful Campaign for Art—demonstrates the legacy of renowned collectors Etta and Claribel Cone and the BMA’s continued relationship with members of the Matisse family. “Etta and Claribel Cone’s dedication to collecting the art of Matisse established at the BMA one of the most comprehensive collections of the artist’s work,” said Jay Fisher, Interim Co-Director and Deputy Director of Curatorial Affairs. “The close personal relationship between the artist and the Cone sisters provided the opportunity to acquire key works from the late ’20s and early ’30s, while encouraging Etta to collect all aspects of his work—painting, sculpture, and graphic arts.” Recognizing the unique character of the BMA’s Matisse collection, the artist’s family has made significant gifts that have added breadth to the museum’s collection. This support, which has included loans for major exhibitions such as Matisse: Painter as Sculptor, has enabled the BMA to organize exhibitions and undertake new research on the artist. -

Osler Library of the History of Medicine Osler Library of the History of Medicine Duplicate Books for Sale, Arranged by Most Recent Acquisition

Osler Library of the History of Medicine Osler Library of the History of Medicine Duplicate books for sale, arranged by most recent acquisition. For more information please visit: http://www.mcgill.ca/osler-library/about/introduction/duplicate-books-for-sale/ # Author Title American Doctor's Odyssey: Adventures in Forty-Five Countries. New York: W.W. Norton, 1936. 2717 Heiser, Victor. 544 p. Ill. Fair. Expected and Unexpected: Childbirth in Prince Edward Island, 1827-1857: The Case Book of Dr. 2716 Mackieson, John. John Mackieson. St. John's, Newfoundland: Faculty of Medicine, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1992. 114 p. Fine. The Woman Doctor of Balcarres. Hamilton, Ontario: Pathway Publications, 1984. 150 p. Very 2715 Steele, Phyllis L. good. The Diseases of Infancy and Childhood: For the Use of Students and Practitioners of Medicine. 2714 Holt, L. Emmett [New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1897.] Special Edition: Birmingham, Alabama: The Classics of Medicine Library, 1980. 1117 p. Ex libris: McGill University. Very Good. The Making of a Psychiatrist. New York: Arbor House, 1972. 410 p. Ex libris: McGill University. 2712 Viscott, David S. Good. Life of Sir William Osler. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1925. 2 vols. 685 and 728 p. Ex libris: McGill 2710 Cushing, Harvey. University. Fair (Rebound). Microbe Hunters. New York: Blue Ribbon Books, 1926. 363 p. Ex Libris: Norman H. Friedman; 2709 De Kruif, Paul McGill University. Very Good (Rebound). History of Medicine: A Scandalously Short Introduction" Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2708 Duffin, Jacalyn. 2000. Soft Cover. Condition: good. Stedman's Medical Dictionary. Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkins Company, 1966. -

Download a PDF of This Issue

Bolton Hill Community Association - https://boltonhillmd.org Bolton Hill Community Association 1 / 17 Bolton Hill Community Association - https://boltonhillmd.org Table Of Contents WHAT LIES AHEAD ... ................................................. 3 BOLTON HILL-BASED SUPPER CLUB HAS CREATED A VIBRANT COMMUNITY .... 5 WOMEN'S HISTORY MONTH ............................................ 7 2020 BOLTON HILL SURVEY FOR RESIDENTS ............................. 10 EVERYONE COUNTS IN BALTIMORE .................................... 11 CITY FARMS 2020 GARDEN SIGN UP IS UNDERWAY ......................... 12 COMMUNITY POLICING PLAN NEEDS FEEDBACK ......................... 13 LONG OVERDUE RENOVATION AT 1700 EUTAW PLACE? .................... 14 ON-STREET PARKING PERMITS DO NOT EXPIRE AT END OF MARCH .......... 16 2 / 17 Bolton Hill Community Association - https://boltonhillmd.org WHAT LIES AHEAD ... https://boltonhillmd.org/bulletin/what-lies-ahead/ Many March events have been canceled or rescheduled as a result of the coronavirus emergency. Please check these dates as they become nearer. CORONAVIRUS UPDATES Check Councilman Costello's website for updates on information about coronavirus from city, state, and federal governments. OPEN HOUSE AT MT. ROYAL ELEMENTARY/MIDDLE SCHOOL Prospective students from Kindergarten to eighth grade and their parents are welcome at the Mt. Royal Elementary and Middle School Open House on Wednesday, April 22, at 9 a.m. This well-regarded public school is located at 121 McMechen Street. LEARN ABOUT THE LUMBEE TRIBE Several interesting lookbacks at earlier times in the city are scheduled over the coming months at the Village Learning Place, 2521 St. Paul Street, hosted by the Baltimore City Historical Society. All are 3 / 17 Bolton Hill Community Association - https://boltonhillmd.org from 7 to 9 p.m., with free admission. On Thursday, April 16, Ashley Minner, a folklore professor at UMBC and a member of the Lumbee Tribe, will speak on Revisiting the Reservation of Baltimore’s Fell’s Point. -

The Autobiography of Alice B Toklas (1933) by Gertrude Stein

The Autobiography of Alice B Toklas (1933) by Gertrude Stein Chapter 1 - BEFORE I CAME TO PARIS I was born in San Francisco, California 1877. California, mid 1800s Alice B. Toklas circa 1878 I have in consequence always preferred living in a temperate climate but it is difficult, on the continent of Europe or even in America, to find a temperate climate and live in it. My mother's father was a pioneer, he came to California in '49, he married my grandmother who was very fond of music. She was a pupil of Clara Schumann's father. My mother was a quiet charming woman named Emilie. My father came of polish patriotic stock. His grand-uncle raised a regiment for Napoleon and was its colonel. His father left his mother just after their marriage, to fight at the barricades in Paris, but his wife having cut off his supplies, he soon returned and led the life of a conservative well to do land owner. I myself have had no liking for violence and have always enjoyed the pleasures of needlework and gardening. I am fond of paintings, furniture, tapestry, houses and flowers and even vegetables and fruit-trees. I like a view but I like to sit with my back turned to it. I led in my childhood and youth the gently bred existence of my class and kind. I had some intellectual adventures at this period but very quiet ones. When I was about nineteen years of age I was a great admirer of Henry James. I felt that The Awkward Age would make a very remarkable play and I wrote to Henry James suggesting that I dramatise it. -

The Medical & Scientific Library of W. Bruce

The Medical & Scientific Library of W. Bruce Fye New York I March 11, 2019 The Medical & Scientific Library of W. Bruce Fye New York | Monday March 11, 2019, at 10am and 2pm BONHAMS LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS INQUIRIES CLIENT SERVICES 580 Madison Avenue AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE New York Monday – Friday 9am-5pm New York, New York 10022 Please email bids.us@bonhams. Ian Ehling +1 (212) 644 9001 www.bonhams.com com with “Live bidding” in Director +1 (212) 644 9009 fax the subject line 48 hrs before +1 (212) 644 9094 PREVIEW the auction to register for this [email protected] ILLUSTRATIONS Thursday, March 7, service. Front cover: Lot 188 10am to 5pm Tom Lamb, Director Inside front cover: Lot 53 Friday, March 8, Bidding by telephone will only be Business Development Inside back cover: Lot 261 10am to 5pm accepted on a lot with a lower +1 (917) 921 7342 Back cover: Lot 361 Saturday, March 9, estimate in excess of $1000 [email protected] 12pm to 5pm REGISTRATION Please see pages 228 to 231 Sunday, March 10, Darren Sutherland, Specialist IMPORTANT NOTICE for bidder information including +1 (212) 461 6531 12pm to 5pm Please note that all customers, Conditions of Sale, after-sale [email protected] collection and shipment. All irrespective of any previous activity SALE NUMBER: 25418 with Bonhams, are required to items listed on page 231, will be Tim Tezer, Junior Specialist complete the Bidder Registration transferred to off-site storage +1 (917) 206 1647 CATALOG: $35 Form in advance of the sale. -

The Radical Ekphrasis of Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons Georgia Googer University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2018 The Radical Ekphrasis Of Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons Georgia Googer University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Recommended Citation Googer, Georgia, "The Radical Ekphrasis Of Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons" (2018). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 889. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/889 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RADICAL EKPHRASIS OF GERTRUDE STEIN’S TENDER BUTTONS A Thesis Presented by Georgia Googer to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in English May, 2018 Defense Date: March 21, 2018 Thesis Examination Committee: Mary Louise Kete, Ph.D., Advisor Melanie S. Gustafson, Ph.D., Chairperson Eric R. Lindstrom, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College ABSTRACT This thesis offers a reading of Gertrude Stein’s 1914 prose poetry collection, Tender Buttons, as a radical experiment in ekphrasis. A project that began with an examination of the avant-garde imagism movement in the early twentieth century, this thesis notes how Stein’s work differs from her Imagist contemporaries through an exploration of material spaces and objects as immersive sensory experiences. This thesis draws on late twentieth century attempts to understand and define ekphrastic poetry before turning to Tender Buttons. -

Gertrude Stein's "Melanctha" and the Problem of Female Empowerment

Moving Away from Nineteenth Century Paradigms: Gertrude Stein's "Melanctha" and the Problem of Female Empowerment Adrianne Kalfopoulou Aristotle Udiversity Thessaloniki The increasing visibility of a self in process motivated by either conscious or unconscious desire-some assertion of the self in conflict with the structural boundaries of gendered, racist conduct-marks one expression of a general movement at the turn-of-the-century away from the given canons of nineteenth century historicity. With Three Lives, a pioneering, modernist work published in 1909, Gertrude Stein takes direct issue with nineteenth century paradigms of proper gender conduct, emphasizing their cultural/linguistic construct as opposed to what, historically, were considered their natural/biological character.1 In "Melanctha," the second and longest of the three narratives that make up Three Lives, we are introduced to the mulatto heroine Melanc- tha whose restless complexity does not allow her to settle into any of the conventional female roles. From the first, the traditional constructs of wife and motherhood with their implicit propriety are questioned. Rose Johnson, Melanctha's black friend, is the one who is married, the one who has given birth. But while Melanctha is "patient, submissive, soothing, and untiring" (81) in her regard for Rose and her baby, Rose herself is "careless, negligent, and selfish" toward Melanctha and, more importantly, toward her own child.2 We are told that Rose's negligence 1 (New York: Signet Classic [1909) 1985). 2 Ekaterini Georgoudaki goes into in-depth discussion of black, female stereotypes and how contemporary black women writers work lo revise these inheriled, pre-exisling, cultural and literary stereotypes. -

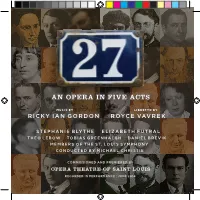

An Opera in Five Acts

AN OPERA IN FIVE ACTS MUSIC BY LIBRETTO BY RICKY IAN GORDON ROYCE VAVREK STEPHANIE BLYTHE ELIZABETH FUTRAL THEO LEBOW TOBIAS GREENHALGH DANIEL BREVIK MEMBERS OF THE ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY CONDUCTED BY MICHAEL CHRISTIE COMMISSIONED AND PREMIERED BY OPERA THEATRE OF SAINT LOUIS RECORDED IN PERFORMANCE : JUNE 2014 1 CD 1 1) PROLOGUE | ALICE KNITS THE WORLD [5:35] ACT ONE 2) SCENE 1 — 27 RUE DE FLEURUS [10:12] ALICE B. TOKLAS 3) SCENE 2 — GERTRUDE SITS FOR PABLO [5:25] AND GERTRUDE 4) SCENE 3 — BACK AT THE SALON [15:58] STEIN, 1922. ACT TWO | ZEPPELINS PHOTO BY MAN RAY. 5) SCENE 1 — CHATTER [5:21] 6) SCENE 2 — DOUGHBOY [4:13] SAN FRANCISCO ACT THREE | GÉNÉRATION PERDUE MUSEUM OF 7) INTRODUCTION; “LOST BOYS” [5:26] MODERN ART. 8) “COME MEET MAN RAY” [5:48] 9) “HOW WOULD YOU CHOOSE?” [4:59] 10) “HE’S GONE, LOVEY” [2:30] CD 2 ACT FOUR | GERTRUDE STEIN IS SAFE, SAFE 1) INTRODUCTION; “TWICE DENYING A WAR” [7:36] 2) “JURY OF MY CANVAS” [6:07] ACT FIVE | ALICE ALONE 3) INTRODUCTION; “THERE ONCE LIVED TWO WOMEN” [8:40] 4) “I’VE BEEN CALLED MANY THINGS" [8:21] 2 If a magpie in the sky on the sky can not cry if the pigeon on the grass alas can alas and to pass the pigeon on the grass alas and the magpie in the sky on the sky and to try and to try alas on the grass the pigeon on the grass and alas. They might be very well very well very ALICE B.