•Œmoney Alone Was Not Enoughâ•Š: Continued Gendering of Womenâ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 23, No. 8 August 2019 You Can’T Buy It

ABSOLUTELY FREE Vol. 23, No. 8 August 2019 You Can’t Buy It As Above, So Below Artwork is by Diane Nations and is part of her exhibit Under the Influence of Jung on view at Artworks Gallery in Winston-Salem, North Carolina through August 31, 2019. See the article on Page 28. ARTICLE INDEX Advertising Directory This index has active links, just click on the Page number and it will take you to that page. Listed in order in which they appear in the paper. Page 1 - Cover - Artworks Gallery (Winston-Salem) - Diane Nations Page 3 - Ella Walton Richardson Fine Art Page 2 - Article Index, Advertising Directory, Contact Info, Links to blogs, and Carolina Arts site Page 5 - Wells Gallery at the Sanctuary & Halsey MCallum Studio Page 4 - Redux Contemporary Art Center & Charleston Artist Guild Page 6 - Thomas Dixon for Mayor & Jesse Williams District 6 Page 5 - Charleston Museum & Robert Lange Studios Page 7 - Emerge SC, Helena Fox Fine Art, Corrigan Gallery, Halsey-McCallum Studio, Page 6 - Robert Lange Studios cont., Ella Walton Richardson Fine Art & Rhett Thurman, Anglin Smith Fine Art, Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art, Lowcountry Artists Gallery The Wells Gallery at the Sanctuary & Saul Alexander Foundation Gallery Page 9 - Lowcountry Artists Gallery cont. & Halsey Institute / College of Charleston Page 8 - Halsey Institute / College of Charleston Page 10 - Halsey Institute / College of Charleston & Art League of Hilton Head Page 9 - Whimsy Joy Page 11 - Art League of Hilton Head cont. & Society of Bluffton Artists Page 10 - Halsey Institute -

Bma Presents Matisse Prints and Drawings

Media Contacts: Anne Brown Jessica Novak Sarah Pedroni 443-573-1870 BMA PRESENTS MATISSE PRINTS AND DRAWINGS New Arrivals exhibition recognizes BMA’s continued relationship with the Matisse family BALTIMORE, MD (December 3, 2015)—The Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) presents a sublime exhibition of works by Henri Matisse, one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. On view December 9, 2015-July 3, 2016, New Arrivals: Matisse Prints & Drawings features approximately 40 recently acquired prints and drawings, most bestowed to the BMA by the collection of Matisse’s daughter, Marguerite Matisse Duthuit, and The Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation in New York. The exhibition—one of nine celebrating the museum’s enormously successful Campaign for Art—demonstrates the legacy of renowned collectors Etta and Claribel Cone and the BMA’s continued relationship with members of the Matisse family. “Etta and Claribel Cone’s dedication to collecting the art of Matisse established at the BMA one of the most comprehensive collections of the artist’s work,” said Jay Fisher, Interim Co-Director and Deputy Director of Curatorial Affairs. “The close personal relationship between the artist and the Cone sisters provided the opportunity to acquire key works from the late ’20s and early ’30s, while encouraging Etta to collect all aspects of his work—painting, sculpture, and graphic arts.” Recognizing the unique character of the BMA’s Matisse collection, the artist’s family has made significant gifts that have added breadth to the museum’s collection. This support, which has included loans for major exhibitions such as Matisse: Painter as Sculptor, has enabled the BMA to organize exhibitions and undertake new research on the artist. -

Download a PDF of This Issue

Bolton Hill Community Association - https://boltonhillmd.org Bolton Hill Community Association 1 / 17 Bolton Hill Community Association - https://boltonhillmd.org Table Of Contents WHAT LIES AHEAD ... ................................................. 3 BOLTON HILL-BASED SUPPER CLUB HAS CREATED A VIBRANT COMMUNITY .... 5 WOMEN'S HISTORY MONTH ............................................ 7 2020 BOLTON HILL SURVEY FOR RESIDENTS ............................. 10 EVERYONE COUNTS IN BALTIMORE .................................... 11 CITY FARMS 2020 GARDEN SIGN UP IS UNDERWAY ......................... 12 COMMUNITY POLICING PLAN NEEDS FEEDBACK ......................... 13 LONG OVERDUE RENOVATION AT 1700 EUTAW PLACE? .................... 14 ON-STREET PARKING PERMITS DO NOT EXPIRE AT END OF MARCH .......... 16 2 / 17 Bolton Hill Community Association - https://boltonhillmd.org WHAT LIES AHEAD ... https://boltonhillmd.org/bulletin/what-lies-ahead/ Many March events have been canceled or rescheduled as a result of the coronavirus emergency. Please check these dates as they become nearer. CORONAVIRUS UPDATES Check Councilman Costello's website for updates on information about coronavirus from city, state, and federal governments. OPEN HOUSE AT MT. ROYAL ELEMENTARY/MIDDLE SCHOOL Prospective students from Kindergarten to eighth grade and their parents are welcome at the Mt. Royal Elementary and Middle School Open House on Wednesday, April 22, at 9 a.m. This well-regarded public school is located at 121 McMechen Street. LEARN ABOUT THE LUMBEE TRIBE Several interesting lookbacks at earlier times in the city are scheduled over the coming months at the Village Learning Place, 2521 St. Paul Street, hosted by the Baltimore City Historical Society. All are 3 / 17 Bolton Hill Community Association - https://boltonhillmd.org from 7 to 9 p.m., with free admission. On Thursday, April 16, Ashley Minner, a folklore professor at UMBC and a member of the Lumbee Tribe, will speak on Revisiting the Reservation of Baltimore’s Fell’s Point. -

The Autobiography of Alice B Toklas (1933) by Gertrude Stein

The Autobiography of Alice B Toklas (1933) by Gertrude Stein Chapter 1 - BEFORE I CAME TO PARIS I was born in San Francisco, California 1877. California, mid 1800s Alice B. Toklas circa 1878 I have in consequence always preferred living in a temperate climate but it is difficult, on the continent of Europe or even in America, to find a temperate climate and live in it. My mother's father was a pioneer, he came to California in '49, he married my grandmother who was very fond of music. She was a pupil of Clara Schumann's father. My mother was a quiet charming woman named Emilie. My father came of polish patriotic stock. His grand-uncle raised a regiment for Napoleon and was its colonel. His father left his mother just after their marriage, to fight at the barricades in Paris, but his wife having cut off his supplies, he soon returned and led the life of a conservative well to do land owner. I myself have had no liking for violence and have always enjoyed the pleasures of needlework and gardening. I am fond of paintings, furniture, tapestry, houses and flowers and even vegetables and fruit-trees. I like a view but I like to sit with my back turned to it. I led in my childhood and youth the gently bred existence of my class and kind. I had some intellectual adventures at this period but very quiet ones. When I was about nineteen years of age I was a great admirer of Henry James. I felt that The Awkward Age would make a very remarkable play and I wrote to Henry James suggesting that I dramatise it. -

Pioneering Women Ignored for Half a Century; Resurrected by Mary Gabriel in Acclaimed Biography

FOR MORE INFORMA- TION, CONTACT: Elly Zupko Assistant to the Attention: Book Buyer Publisher Bancroft Press 410-358-0658 ezupko@ bancroftpress.com Pioneering Women Ignored For Half a Century; Resurrected by Mary Gabriel in Acclaimed Biography IT’S ENTIRELY them anxious to house their hitherto private probable you missed assemblage of modern art. them the first time, when they were IN 1949, WITHOUT SELLING a single pur- flouncing around chase to outside interests or bequeathing a Europe at the turn of single piece to a relative or friend, they the last century. In awarded all their holdings to the Baltimore fact, most of history Museum of Art. In 2002, that collection was did. They are two of conservatively valued at $1 billion, thus the most interesting making them two of the most philanthropic and important art collectors of our age. But numbers aside, women in American if you’ve been lucky enough to see the Cone and world history, and they were almost Wing at the BMA, you know the collection forgotten. simply cannot be valued. IT’S EQUALLY POSSIBLE you missed them “Highly readable combination of in- the second time, when author-historian sights on collecting, and fresh, well- Mary Gabriel brought them back to life one rounded portraits of two remarkable hundred years later in her book The Art of collectors”-- MICHAEL PALIN, HOST/ Acquiring. These women got a second PRODUCER, BBC DOCUMENTARY, chance at assuming their rightful place as “MICHAEL PALIN & THE LADIES WHO history-makers. LOVED MATISSE” IT WOULD SIMPLY be a tragedy to miss them again. -

Download the Nasher 2013 Annual Report

Mission Statement The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University promotes engagement with the visual arts among a broad community including Duke students, faculty and staff, the greater Durham community, the Triangle region and the national and international art community. The museum is dedicated to an innovative approach, and presents collections, exhibitions, publications and programs that attain the highest level of artistic excellence, stimulate intellectual discourse, enrich individual lives and generate new knowledge in the service of society. Drawing on the resources of a leading research university, the museum serves as a laboratory for interdisciplinary approaches to embracing and understanding the visual arts. Box 90732 | Durham, NC 27708 | 919-684-5135 | nasher.duke.edu COVER Wangechi Mutu’s 2013 installation of Suspended Playtime greeted visitors to her solo exhibition at the Nasher Museum. The artist’s mixed-media collages, Funkalicious fruit field (2007) and People in Glass Towers Should Not Imagine Us (2003), are visible through the installation made of packing blankets, twine, garbage bags and gold string. Photo by Peter Paul Geoffrion. 2013 ANNUAL REPORT CLOCKWISE Duke Provost Peter Lange and his wife Lori Leachman absorb photographs in Light Sensitive. Dancers from Duke’s African Repertory Dance Ensemble liven up the Great Hall during a free Art for All event. Nasher Museum Director Sarah Schroth accepted her new appointment in June 2013. A family engages with Matisse’s famous painting, Large Reclining Nude, in Collecting Matisse and Modern Masters. Duke students regard Mark Bradford’s monumental 2005 mixed- media collage, Potable Water. All photos by J Caldwell. FROM THE DIRECTOR I am delighted to have the opportunity to lead the Nasher joined as a result of a direct mail campaign and encouraged the Nasher Museum to think about Museum in what promises to be a very exciting time, as media outreach. -

GRADUATE PROGRAM in the HISTORY of ART Williams College/Clark Art Institute

GRADUATE PROGRAM IN THE HISTORY OF ART Williams College/Clark Art Institute Summer 2003 NEWSLETTER The Class of 2003 at its Hooding Ceremony. Front row, from left to right: Pan Wendt, Elizabeth Winborne, Jane Simon, Esther Bell, Jordan Kim, Christa Carroll, Katie Hanson; back row: Mark Haxthausen, Ben Tilghman, Patricia Hickson, Don Meyer, Ellery Foutch, Kim Conary, Catherine Malone, Marc Simpson LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR CHARLES w.: (MARK) HAxTHAUSEN Faison-Pierson-Stoddard Professor of Art History, Director of the Graduate Program With the 2002-2003 academic year the Graduate Program began its fourth decade of operation. Its success during its first thirty years outstripped the modest mission that shaped the early planning for the program: to train for regional colleges art historians who were drawn to teaching careers yet not inclined to scholarship and hence having no need to acquire the Ph.D. (It was a different world then!) Initially, those who conceived of the program - members of the Clark's board of trustees and Williams College President Jack Sawyer - seem never to have imagined that it would attain the preeminence that it quickly achieved under the stewardship of its first directors, George Heard Hamilton, Frank Robinson, and Sam Edgerton. Today the Williams/Clark program enjoys an excellent reputation for preparing students for museum careers, yet this was never its declared mission; unlike some institutions, we have never offered a degree or even a specialization in "museum studies" or "museology." Since the time of George Hamilton, the program has endeavored simply to train art historians, and in doing so it has assumed that intimacy with objects is a sine qua non for the practice of art history. -

The Cone Sisters' Apartments: Creating a Real-Time, Interactive Virtual Tour

“THE CONE SISTERS’ APARTMENTS: CREATING A REAL-TIME, INTERACTIVE VIRTUAL TOUR” Allison C. Perkins, The Baltimore Museum of Art, USA Dan Bailey, Imaging Research Center University of Maryland at Baltimore County, USA Alan Price, Associate Professor, Visual Arts Research Associate, Imaging Research Center University of Maryland at Baltimore County, USA ICHIM 03 – Virtual Reality : Content and Interfaces / Réalités Virtuelles : Contenu et Interfaces Abstract This paper summarizes and presents the results of a unique collaboration between The Baltimore Museum of Art and the Imaging Research Center at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, USA. The collaboration yielded a major visualization project that can be presented as both a real-time interactive simulation in the Museum’s galleries and a large-scale immersive experience. This visualization of interior living spaces that no longer exist provides a highly detailed record of how Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone, two wealthy Baltimore art collectors and patrons, filled their apartments with their incomparable collection of art by the French master Henri Matisse and other European post-Impressionist and modern artists. The experience provides a rich visual and historic context for museum visitors’ understanding and appreciation of the collection that now forms the cornerstone of The Baltimore Museum of Art’s permanent holdings. Keywords: Virtual Reconstruction, Collaboration, Interactive, Visualization, Interpretive, Historical Context, Virtual Tour Reinstalling The Cone Collection at The Baltimore Museum of Art: Opportunities for New Interpretive Strategies The Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA), Baltimore, Maryland, USA, is home to The Cone Collection, an exceptional group of 500 works by Matisse, considered the most important and comprehensive holding in the world. -

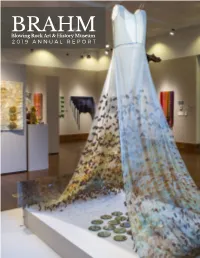

2019 Annual Report

BRAHM Blowing Rock Art & History Museum 2 0 1 9 A N N U A L R E P O R T S T A F F B O A R D O F T R U S T E E S L e e C a r o l G i d u z B o H e n d e r s o n , P r e s i d e n t E x e c u t i v e D i r e c t o r N e l s o n C r i s p , V i c e P r e s i d e n t C o u r t n e y B a i n e s D o n H u b b l e , T r e a s u r e r M a r k e t i n g & C o m m u n i c a t i o n s T e r e s a C a i n e , S e c r e t a r y D i r e c t o r J e s s W e h r m a n n , A t - L a r g e M e m b e r M a r k B r a c k b i l l F a c i l i t i e s M a n a g e r D e b b i e C o v i n g t o n S h a r o n C a l d w e l l J o e C o y n e O f f i c e M a n a g e r C a r o l B i g g e r s D a b b s D i a n n a C a m e r o n C u r a t o r o f L i n d a G i l l e l a n d E x h i b i t i o n s L o u i s N . -

The Art of Acquiring a Portrait of Etta and Claribel Cone

The Art of Acquiring A Portrait of Etta and Claribel Cone By Mary Gabriel BOOK SUMMARY: Mary Gabriel tells the story of Etta and Claribel Cone, two independently wealthy Jewish women from Baltimore who acquired one of the most important collections of modern French painting in the world; two upright, Victorian sisters who collected Matisse, Picasso, Cezanne, Renoir, Degas, Gaughin; who collected even the most scandalous art of the time, from Matisse's Blue Nude, to his Pink Nude. Life-long fans of Matisse, the women bought him before anyone else would even take him seriously. In fact, Matisse and Etta often said to each other something to the effect of, "Remember, I made you;" the two made each other: into one the most important artists of BOOK INFO the twentieth century, and one of the most sought-after collectors of our time. The Art of Acquiring: A Portrait of Etta and Claribel Cone traces the Cone ISBN sisters from their early family life to their deaths, and provides information on the state of the 1-890862-06-1 collection today. Gabriel's biography is a crucial contribution to both the study of art history Price and women's history: she resurrects not only two powerful, influential, ahead-of-their-time $ 35.00 women; she resurrects the study—the art—of collecting. Collecting, Gabriel points out, is not Pub. Date simply a hobby of the rich; it is a careful, precise craft. Although they easily could have lived September 2002 luxurious, superficial lives of good food, wine, and clothing, Etta and Claribel Cone chose to Category contribute to the livelihood of artists in whom they believed, and to preserve—in the most Art History/ perfect condition possible—the great contributions of artists of our century. -

The Museum of Modern Art NO. 133

-vt* The Museum of Modern Art NO. 133 11 am - 4 pm STEIN COLLECTIONS ON VIEW AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART FOUR AMERICANS IN PARIS: THE COLLECTIONS OF CERTEUDE STEIN AND KER FAMILY will be on view at The Museum of Modern Art from December 19 through March 1. Sponsored by Alcoa Foun dation, the exhibition of more than 200 vrorks represents the first attempt to reassemble the paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints acquired by this extraordinary family, x^jho were early, ardent patrons of Matisse and Picasso in the first decades of this century. From about 1905 on, an international assemblage of artists, writers, musicians and intellectuals gathered regularly in their Paris apartments to look, listen, talk and be introduced to the revolutionary art of our time. Directed by Margaret Potter, Associate Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture, the show includes many paintings long recognized as masterpieces of the 20th century, other important works that are virtually unknown, and portraits, sketches and documentary photo graphs. Together, these evoke a highly significant moment in the history of art and illu minate the personalities of the four members of this noted family: Gertrude, her brothers Leo and Michael, and the latter's wife, Sarah. Nucleus of the exhibition is formed by the 47 works — 38 by Picasso and 9 by Gris — acquired by five American collectors from the Estate of Gertrude Stein in 1968. It was decided to reassemble around these as many as possible of the works once owned by Gertrude, Leo, Michael and Sarah Stein. Because their collections had been gradually dispersed over many years, the loans have been gathered from some 90 institutions and individuals ranging geographically from the USSR to Australia, and from Norway to Mexico. -

BMA Exhibition Captures Significance of the 43-Year Friendship Between Baltimore Collector Etta Cone and Artist Henri Matisse

BMA Exhibition Captures Significance of the 43-Year Friendship Between Baltimore Collector Etta Cone and Artist Henri Matisse For media in More than 160 Artworks—Including Rarely Seen Works on Paper— Baltimore: Illuminate the Vision of this Important Collector and Her Role in Anne Brown Creating an Unparalleled Public Resource 410-274-9907 [email protected] BALTIMORE, MD (May 24, 2021)—This fall, the Baltimore Museum of Art For media outside (BMA) will present the first comprehensive exhibition to explore the singular Baltimore: 43-year friendship between Baltimore collector Etta Cone (1870-1949) and Alina E. Sumajin PAVE Communications French modern master Henri Matisse (1869-1954). Their relationship laid the & Consulting foundation for the BMA’s Matisse collection, which with more than 1,200 646-369-2050 paintings and works on paper is the largest public collection of the artist’s work [email protected] in the world. A Modern Influence: Henri Matisse, Etta Cone, and Baltimore will include more than 160 paintings, sculptures, prints, drawings, and illustrated books that demonstrate how Cone’s bond with the artist provided her with a sense of identity, purpose, and freedom from convention. The exhibition will be accompanied by a scholarly catalogue that includes research on the formal, technical, and social aspects of their artistic and collecting practices, as well as Cone’s seminal role in bringing European modernism to the United States. On view October 3, 2021–January 2, 2022, the exhibition precedes the December 2021 opening of the Ruth R. Marder Center for Matisse Studies at the BMA, which will allow for greater public and scholarly engagement with the museum’s Matisse collection.