Representation Through Privatisation Regionalization of Forest Governance in Tambacounda, Senegal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Road Travel Report: Senegal

ROAD TRAVEL REPORT: SENEGAL KNOW BEFORE YOU GO… Road crashes are the greatest danger to travelers in Dakar, especially at night. Traffic seems chaotic to many U.S. drivers, especially in Dakar. Driving defensively is strongly recommended. Be alert for cyclists, motorcyclists, pedestrians, livestock and animal-drawn carts in both urban and rural areas. The government is gradually upgrading existing roads and constructing new roads. Road crashes are one of the leading causes of injury and An average of 9,600 road crashes involving injury to death in Senegal. persons occur annually, almost half of which take place in urban areas. There are 42.7 fatalities per 10,000 vehicles in Senegal, compared to 1.9 in the United States and 1.4 in the United Kingdom. ROAD REALITIES DRIVER BEHAVIORS There are 15,000 km of roads in Senegal, of which 4, Drivers often drive aggressively, speed, tailgate, make 555 km are paved. About 28% of paved roads are in fair unexpected maneuvers, disregard road markings and to good condition. pass recklessly even in the face of oncoming traffic. Most roads are two-lane, narrow and lack shoulders. Many drivers do not obey road signs, traffic signals, or Paved roads linking major cities are generally in fair to other traffic rules. good condition for daytime travel. Night travel is risky Drivers commonly try to fit two or more lanes of traffic due to inadequate lighting, variable road conditions and into one lane. the many pedestrians and non-motorized vehicles sharing the roads. Drivers commonly drive on wider sidewalks. Be alert for motorcyclists and moped riders on narrow Secondary roads may be in poor condition, especially sidewalks. -

Teranga Development Strategy

TERANGA DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY FEBRUARY 2014 PREPARED BY TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE TDS 5 1.2 OUR PRIORITY OUTCOMES 7 1.3 OUR FOCUS AREA 8 1.4 MYTHODOLOGY 10 1.5 DOCUMENT STRUCTURE 14 2.0 OUR MINE OPERATION 15 2.1 THE SABODALA GOLD OPERATION 16 2.2 OUR FUTURE GROWTH 18 3.0 UNDERSTANDING OUR REGION 20 3.1 INTRODUCTION 21 3.2 GOVERNANCE 22 3.3 DEVELOPMENT PLANNING 27 3.4 AGRICULTURE AND LIVELIHOOD 31 3.5 EDUCATION 38 3.6 ENERGY AND INFRASTRUCTURE 46 3.7 TRANSPORTATION INFRASTRUCTURE 50 3.8 HEALTH, SAFETY AND SECURITY 53 3.9 WATER INFRASTRUCTURE 66 3.10 SANITATION INFRASTRUCTURE 70 3.11 HOUSING 72 3.12 ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION 74 4.0 OUR VISION FOR OUR ROLE IN THE REGION 79 5.0 A SPATIAL STRUCTURE TO SUPPORT REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 81 5.1 INTRODUCTION 82 5.2 THE GOLD DISTRICT CONCEPTUAL SPATIAL PLAN 87 2 6.0 OUR ACTIONS 92 6.1 INTRODUCTION 93 6.2 JOBS AND PEOPLE DEVELOPMENT 94 6.3 LAND ACQUISITION 102 6.4 PROCUREMENT 106 6.5 HEALTH, SAFETY AND SECURITY 110 6.6 MINE-RELATED INFRASTRUCTURE 116 6.7 WORKER HOUSING 119 6.8 COMMUNITY RELATIONS 121 6.9 MINE CLOSURE AND REHABILITATION 125 6.10 FINANCIAL PAYMENTS AND INVESTMENTS 129 LIST OF ACRONYMS 143 TERANGA DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 3 SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE TDS As the first gold mine in Senegal, Teranga has a unique opportunity to set the industry standard for socially responsible mining in the country. -

I. Project Context and Development Objectives ...5

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: ICR00005096 IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION AND RESULTS REPORT IDA-47370; IDA-57310 ON CREDITS Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 71.9 MILLION (US$105 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL Public Disclosure Authorized FOR A SENEGAL: TRANSPORT AND URBAN MOBILITY PROJECT June 17, 2020 Transport Global Practice Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective April 30, 2020) Currency Unit = CFA Francs ( XO F) XOF 603= US$1 US$ 1.37= SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR July 1 – June 30 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AFTU Urban Transport Financing Association (Association de Financement des Transports Urbains) AGEROUTE Road Management Agency (Agence des Travaux et de Gestion des Routes) AF Additional Financing BRT Bus Rapid Transit CAS Country Assistance Strategy CEREEQ Experimental Research Centre for Equipment Studies CETUD Dakar Urban Transport Council (Conseil Exécutif des Transports Urbains de Dakar) CGQA Air Quality Management Center CPF Country Partnership Framework CPS Country Partnership Strategy DDD Dakar Mass Transit Company (Dakar-Dem-Dik) DGI Infrastructure General Directorate DR Directorate of Roads (Direction des Routes) DTR Directorate of Road Transports (Direction des Transports Routiers) DTT Directorate -

Mali's Infrastructure

COUNTRY REPORT Mali’s Infrastructure: A Continental Perspective Cecilia M. Briceño-Garmendia, Carolina Dominguez and Nataliya Pushak JUNE 2011 © 2011 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 USA Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved A publication of the World Bank. The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 USA The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

Climate Change and Health Risks in Senegal

0f TECHNICAL REPORT CLIMATE CHANGE AND HEALTH RISKS IN SENEGAL September 2015 This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics for the ATLAS Task Order. This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics for the Climate Change Adaptation, Though Leadership, and Assessments (ATLAS) Task Order No. AID-OAA-I-14-00013, under the Restoring the Environment through Prosperity, Livelihoods, and Conserving Ecosystems (REPLACE) IDIQ. Chemonics Contact: Chris Perine, Chief of Party ([email protected]) Chemonics International Inc. 1717 H Street NW Washington, DC 20006 Cover Photo: A woman practices good mosquito net care and repair, a key component of campaigns in Senegal with NetWorks and the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP). © 2011 NetWorks Senegal/CCP, Courtesy of Photoshare CLIMATE CHANGE AND HEALTH RISKS IN SENEGAL September 2015 Prepared for: United States Agency for International Development Climate Change Adaptation, Thought Leadership and Assessments (ATLAS) Prepared by: Fernanda Zermoglio (Chemonics International) Anna Steynor (Climate Systems Analysis Group, University of Cape Town) Chris Jack (Climate Systems Analysis Group, University of Cape Town) This report is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Chemonics and do not necessarily -

Africa Riskview END of SEASON REPORT | SENEGAL (2017 SEASON)

Africa RiskView END OF SEASON REPORT | SENEGAL (2017 SEASON) This Africa RiskView End-of-Season Report is a publication by the African Risk Capacity (ARC). The report discusses Africa RiskView’s estimates of rainfall, drought and population affected, comparing them to information from the ground and from external sources. It also provides the basis of a validation exercise of Africa RiskView, which is conducted in each country at the end of an insured season. This exercise aims at reviewing the performance of the model and ensuring that the country’s drought risk is accurately reproduced by Africa RiskView for drought monitoring and insurance coverage. The End-of-Season reports are also being continuously refined with a view to providing early warning to ARC member countries. Highlights: Rainfall: previous five years in the central parts and 90%-110% of the • Comparison of the cumulative rainfall received in 2017 to the median in the western and southern parts of Senegal long term mean (1983-2016) at the pixel level reveals that • The overall performance of the 2017 cropping season was most parts of Senegal received between 110% and 150% of modelled as better than average by Africa RiskView in most their long-term average, implying that above average rainfall parts of Senegal was received during the 2017 season Affected Populations: Drought: • The modelled estimates of Africa RiskView indicate that no • The final end-of-season WRSI for the 2017 season shows that households were affected by drought in the 2017 production 95% to 100% of crop water requirements were met for the season southern and central regions of Senegal—a pointer of ade- RISK POOL quate precipitation • Since a payout of over USD 16 million in 2014/15 due to the • Comparison of the end-of-season WRSI with the benchmark poor performance of the 2014 agricultural season in West Afri- (median WRSI for the previous five years) indicates that the ca, Senegal has not received a payout. -

WEST AFRICA LIBYA 25° ALGERIA 25° WEST Western AFRICA Sahara Tamanrasset Fdérik

20° 15° 10° 5° 0° 5° 10° 15° WEST AFRICA LIBYA 25° ALGERIA 25° WEST Western AFRICA Sahara Tamanrasset Fdérik Nouâdhibou Atâr 20° Akjoujt MAURITANIA 20° Tidjikja Kidal Nouakchott MALI A NIGER T Aleg Tombouctou Agadez Rosso Sene Kiffa 'Ayoûn el 'Atroûs gal L Gao Kaédi Saint-Louis A Louga Matam Sélibabi Tahoua 15° N Dakar Lake 15° Kayes Chad Kaolack SENEGAL Tillabéri T Mopti mbia Tambacounda Zinder CHAD Ga er Niamey Maradi I ig Diffa GAMBIA N Ségou BURKINA Dosso Sokoto C Banjul Kolda Koulikoro FASO Dédougou Katsina Ziguinchor Bamako Ouagadougou Kano Bissau Birnin Kebbi Gusau Maiduguri Koudougou Fada Dutse GUINEA-BISSAU Bobo- N'Gourma Niger Labé Sikasso Dioulasso Boké Léo Kandi O Mamou Kankan Banfora Kaduna Maroua GUINEA Bolgatanga Bauchi C Kindia BENIN Gombe Wa Jos 10° Faranah Odienné Kara Djougou NIGERIA 10° E Conakry Tamale e Kissidougou Lake Abuja nu Yola A Forécariah SIERRA Korhogo e Makeni Volta B Garoua Guéckédou Ilorin Lafia N Freetown Macenta Touba CÔTE Jalingo LEONE Bo Voinjama Nzérékoré D'IVOIRE Lac de GHANA Ado-Ekiti Makurdi Kenema ManKossou Bouaké TOGO Ibadan Ngaoundéré 25° 24° Sunyani Abomey Yamoussoukro Abeokuta CABO VERDE Dimbokro Santo Antão Robertsport LIBERIA Kumasi Cotonou Ikeja Daloa Lagos Benin City Enugu 17° 17° Monrovia Kakata Ho Santa Luzia Zwedru Guiglo Divo Koforidua Porto- Bamenda São Sal Gagnoa Buchanan Lomé Novo Owerri Bafoussam Vicente Fish Town Accra São Nicolau Cestos City Bight of Benin Calabar 5° Port 5° Greenville Abidjan Cape Harcourt CAMEROON Boa Vista Sekondi- Coast 16° 16° Barclayville San-Pédro Buea ATLANTIC Harper Takoradi Douala Yaoundé OCEAN Malabo São 0 100 200 300 400 500 km 0 50 km The boundaries and names shown and the designations used Tiago EQUATORIAL GUINEA Ébolowa 0 25 mi Maio on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance Fogo by the United Nations. -

Ending Rural Hunger: the Case of Senegal

ENDING RURAL HUNGER The case of Senegal October 2017 www.endingruralhunger.org Ibrahima Hathie, Boubacar Seydi, Lamine Samaké, and Souadou Sakho- Jimbira Dr. Ibrahima Hathie is the Research Director at the Initiative Prospective Agricole et Rurale (IPAR) in Senegal. Boubacar Seydi is a statistician at IPAR. Lamine Samaké is a research assistant at IPAR. Souadou Sakho-Jimbira is a senior researcher at IPAR. Author’s note and acknowledgements This report was prepared by Dr. Ibrahima Hathie, Boubacar Seydi, Lamine Samaké, and Souadou Sakho- Jimbira of the Initiative Prospective Agricole et Rurale as part of the Ending Rural Hunger project led by Homi Kharas. The team at the Africa Growth Initiative within the Global Economy and Development program of the Brookings Institution, led by Eyerusalem Siba and comprising Amy Copley, Christina Golubski, Mariama Sow, and Amadou Sy, oversaw the production of the report. Christina Golubski provided design and editorial assistance. John McArthur provided invaluable feedback on the report. Data support was provided by Lorenz Noe, Krista Rasmussen, and Sinead Mowlds. The authors wish to thank Mariama Kesso Sow, Isseu Dieye, Yacor Ndione, Ahmadou Ly, Ndeye Mbayang Kébé and Mayoro Diop for their support in data collection and in interviews with key stakeholders. We are also grateful to many people (civil servants, donors, technical assistance) who have graciously accepted to share their views. This study was supported by a grant from Brookings. This paper reflects the views of the author only and not those of the Africa Growth Initiative. The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. -

Senegal's Infrastructure: a Continental Perspective

COUNTRY REPORT Senegal’s Infrastructure: A Continental Perspective Clemencia Torres, Cecilia M. Briceño-Garmendia, and Carolina Dominguez JUNE 2011 © 2011 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 USA Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved A publication of the World Bank. The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 USA The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple Ŕ Un but Ŕ Une Foi

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple Ŕ Un But Ŕ Une Foi MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE ET DES FINANCES SERVICE REGIONAL DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE DE TAMBACOUNDA SITUATION ECONOMIQUE ET SOCIALE DE LA REGION DE TAMBACOUNDA Ŕ 2008 JUIN - 2008 COMITE DE REDACTION Président : Babakar FALL, Directeur Général ANSD Vice Président : Mamadou Falou MBENGUE, Directeur Général Adjoint ANSD Coordonnateur Général : Mamadou NDAO, Coordonnateur de l’Action Régionale Equipe technique : Samba Gallo BA, Chef de Service Régional Awa Mady KABA, Adjoint Chef de Service Régional Mouhadji DAFF, Informaticien Service Régional de la Statistique et de la Démographie de Tambacounda Quartier Ŕ Liberté. Ŕ Téléphone / fax : (221) 33 981 11 82 / 33 981 00 44 Site Internet : www.ansd.sn 2 BIBLIOGRAPHIE Situation Economique et Sociale de la région de Tambacounda, Editions de 2000 à 2007 du Service régional de la Statistique et de la Démographie. Projections démographiques de la Population du SENEGAL, ANSD Rapport de l’Inspecteur d’Académie de Tambacounda Rapport régional 2008 de l’Inspection Régionale des eaux et Forêts de Tambacounda Evaluation de la GOANA an1-2008/2009, DRDR Rapports de Commercialisation de l’arachide au 30 mars 2009, DRDR Rapport du Service régional des Pêches de Tambacounda Rapport de l’Inspection régionale des Services vétérinaires Rapport du Service régional de l’hygiène Rapports d’activités des Postes de Santé de la région, Région Médicale 3 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tab 1 : Superficie et densité de la région de Tambacounda ................................................................................................................ 16 Tab 2 : Evolution de la population de la région de Tamba selon les localités ...................................................................................... 17 Tab 3 : Superficie et densité de la région de Kédougou ...................................................................................................................... -

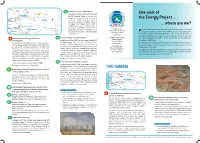

Site Visit of the Energy Project ... the GAMBIA ... Where Are

Kaolack KAFFRINE Birkilane L1b L1a Koungheul L3a Kedougou (Senegal) - Mali (Guinea) L6b Tambacoundaa KAOLACK D1 TAMBACOUNDA A single-circuit line 59 km long, supported Site visit of GAMBIA RIVER BASIN DEVELOPMENT THE GAMBIA ORGANISAbyTION 152 triangular towers. 26 km are in the KANIFING CENTRAL RIVER ORGANISATION POUR LA MISE EN VALEUR DU FLEUVE GASenegaleseMBIE territory and 33 km in Guinea. No UPPER RIVER L2 the Energy Project ... Energy Project Brikama Soma WEST COASTT L7 SENEGAL construction activities have yet started on L6a this section because of problems related to SEDHIOU KOLDA the bypass of the "Bassari country", which is ZIGUINCHOR ... where are we? KEDOUGOU OMVG Tana a UNESCO-protected site, measures aimed at LD1 protecting areas identified as natural habitats for Sambangalou L5d ORGANISATION OOIO GUINEABISSAU chimpanzees, change to the delineation due to rior to our visit to the work sites in The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea and BAFATA POUR LA MISE EN VALEUR L3a the substation site relocation from Sambangalou Senegal, it should be mentioned that OMVG’s new transformer substations Mansoaoa GABU P BBambadinca DU FLEUVE GAMBIE CACHEU L5c L5e Mali to Kedougou, etc.). - Projet Energie - are built on surfaces measuring between 2 and 15 ha, all fully free of Bissau L5b environmental burdens and constraints. Accommodation for future operating Saltinho L3b Tanaff (Senegal) - Soma (The Gambia) GAMBIA RIVER BASIN P1b Tambacounda and Kedougou substations L6aLABE and on-site maintenance staff is under construction at all substations GUINEA DEVELOPMENT (Sambangalou) A single-circuit line 95.22 km long, supported by 205 throughout the OMVG loop. Labé ORGANISATION TOMBALI BOKE triangular towers. -

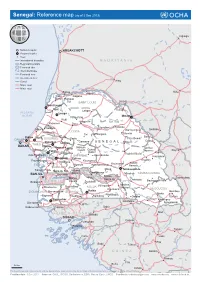

M a U R I T a N I a G U I N E a M a L I Guinea-Bissau Gambia

Senegal: Reference map (as of 3 Dec 2013) Tidjikdja National capital NOUAKCHOTT Regional capital Town International boundary MAURITANIA Regional boundary Perennial lake Intermittent lake Perennial river Intermittent river Canal Aleg Major road Minor road Sénégal Rosso Kiffa Podor Ross Dagana Béthio Richard Toll SAINT LOUIS Kaédi Saint Louis Mpal Labgar Thilogne ATLANTIC Louga OCEAN Matam Yang-Yang Koki Linguère MATAM Kébémèr Dara Ndande Yonoféré Ranérou Mboro Diamounguél Sélibaby Mékhé LOUGA Tiel Vélingara Mamâri Bakel Pikine Thies Touba DAKAR DIOURBEL Sadio Fété Bowé Gassane Gabou Sé Diourbel SENEGAL Mboun négal THIÈS Mbacké DAKAR Niakhar Gossas Mbar Ndioum Sintiou Mbour Guènt Guènt Tapsirou Kayes Fatick Paté Guinguinéo Toubéré Bafal Kidira Joal-Fadhiouth KAFFRINE Lour-Escale Koussane Kaolack Kaffrine Goudiry Foundiougne Ndoffane Koungheul Sokone Koussanar Kotiari FATICK Nganda Koumpentoum Naoude MALI KAOLACK Gambi Maka Tambacounda Karang Poste Nioro du Rip Médina a Sabakh Georgetown TAMBACOUNDA BANJUL Kerewan Missirah Basse Mansa Pata Saïnsoubou Santa Su Dialacoto Boutougou Fara Brikama GAMBIA Konko Soulabali Vélingara Medina Diouloulou Bounkiling KOLDA Gounas Kounkané KÉDOUGOU ZIGUINCHOR Marsassoum SÉDHIOU Kolda Bembou Wassadou Mako Bignona Sédhiou Salikénié Dalaba Saraya Ziguinchor Tiankoye Kédougou Koundara Fongolembi Diembéreng Farim Kabrousse Cacheu Gabú a b Mali GUINEA-BISSAU ê Bafadá G BISSAU Gaoual Fulacunda ia b Bolama m G a Tongué a Catió Labé g n i f a Pita B Boké Telimele GUINEA Dalaba Mamou Fria Boffa 50 Km Kindia The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Creation date: 3 Dec 2013 Sources: GAUL, ISCGM, Bartholomew, ESRI, Natural Earth, UNCS Feedback: [email protected] www.unocha.org www.reliefweb.int.