THE JEWISH DIASPORA the Scattering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARTICLES Israel's Migration Balance

ARTICLES Israel’s Migration Balance Demography, Politics, and Ideology Ian S. Lustick Abstract: As a state founded on Jewish immigration and the absorp- tion of immigration, what are the ideological and political implications for Israel of a zero or negative migration balance? By closely examining data on immigration and emigration, trends with regard to the migration balance are established. This article pays particular attention to the ways in which Israelis from different political perspectives have portrayed the question of the migration balance and to the relationship between a declining migration balance and the re-emergence of the “demographic problem” as a political, cultural, and psychological reality of enormous resonance for Jewish Israelis. Conclusions are drawn about the relation- ship between Israel’s anxious re-engagement with the demographic problem and its responses to Iran’s nuclear program, the unintended con- sequences of encouraging programs of “flexible aliyah,” and the intense debate over the conversion of non-Jewish non-Arab Israelis. KEYWORDS: aliyah, demographic problem, emigration, immigration, Israel, migration balance, yeridah, Zionism Changing Approaches to Aliyah and Yeridah Aliyah, the migration of Jews to Israel from their previous homes in the diaspora, was the central plank and raison d’être of classical Zionism. Every stream of Zionist ideology has emphasized the return of Jews to what is declared as their once and future homeland. Every Zionist political party; every institution of the Zionist movement; every Israeli government; and most Israeli political parties, from 1948 to the present, have given pride of place to their commitments to aliyah and immigrant absorption. For example, the official list of ten “policy guidelines” of Israel’s 32nd Israel Studies Review, Volume 26, Issue 1, Summer 2011: 33–65 © Association for Israel Studies doi: 10.3167/isr.2011.260108 34 | Ian S. -

Migration of Jews to Palestine in the 20Th Century

Name Date Migration of Jews to Palestine in the 20th Century Read the text below. The Jewish people historically defined themselves as the Jewish Diaspora, a group of people living in exile. Their traditional homeland was Palestine, a geographic region on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Jewish leaders trace the source of the Jewish Diaspora to the Roman occupation of Palestine (then called Judea) in the 1st century CE. Fleeing the occupation, most Jews immigrated to Europe. Over the centuries, Jews began to slowly immigrate back to Palestine. Beginning in the 1200s, Jewish people were expelled from England, France, and central Europe. Most resettled in Russia and Eastern Europe, mainly Poland. A small population, however, immigrated to Palestine. In 1492, when King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella expelled all Jewish people living in Spain, some refugees settled in Palestine. At the turn of the 20th century, European Jews were migrating to Palestine in large numbers, fleeing religious persecution. In Russia, Jewish people were segregated into an area along the country’s western border, called the Pale of Settlement. In 1881, Russians began mass killings of Jews. The mass killings, called pogroms, caused many Jews to flee Russia and settle in Palestine. Prejudice against Jews, called anti-Semitism, was very strong in Germany, Austria-Hungary, and France. In 1894, a French army officer named Alfred Dreyfus was falsely accused of treason against the French government. Dreyfus, who was Jewish, was imprisoned for five years and tried again even after new information proved his innocence. The incident, called The Dreyfus Affair, exposed widespread anti-Semitism in Western Europe. -

FFYS 1000.03 – the Holy Land and Jerusalem: a Religious History

First Year Seminar Loyola Marymount University FFYS 1000.03 – The Holy Land and Jerusalem: A Religious History Fall 2013 | T/R 8:00 – 9:15 AM | Classroom: University Hall 3304 Professor: Gil Klein, Ph.D. | Office hours: W 1:30-3:00 PM; T/R 3:30 - 5:00 PM and by appointment Office: UH 3775 | Phone: (310) 338 1732 | Email: [email protected] Writing instructor: Andrew (AJ) Ogilvie, Ph.D. Candidate, UC Santa Barbara Email: [email protected] Course description The Holy Land, with the city of Jerusalem at its center, is where many of the foundational moments in Judaism, Christianity and Islam have occurred. As such, it has become a rich and highly contested religious symbol, which is understood by many as embodying a unique kind of sanctity. What makes it sacred? What led people in different periods to give their life fighting over it? How did it become the object of longing and the subject of numerous works of religious art and literature? What is the secret of the persistent hold it still has on the minds of Jews, Christians and Muslims around the world? This course will explore central moments in the religious history of the Holy Land from ancient times to the present day in an attempt to answer some of these questions. It will do so through the critical analysis of religious text, art and architecture, as well as through the investigation of contemporary culture and politics relating to the Holy Land and Jerusalem. Course structure The structure of this course is based on the historical transformations of the Holy Land and Jerusalem from ancient through modern times, as well as on the main cultural aspects of their development. -

Robert Aaron Kenedy / the New Anti-Semitism and Diasporic 8 Liminality: Jewish Identity from France to Montreal

Robert Aaron Kenedy / The New Anti-Semitism and Diasporic 8 Liminality: Jewish Identity from France to Montreal Robert Aaron Kenedy The New Anti-Semitism and Diasporic Liminality: Jewish Identity from France to Montreal Canadian Jewish Studies / Études juives canadiennes, vol. 25, 2017 9 Through a case study approach, 40 French Jews were interviewed revealing their primary reason for leaving France and resettling in Montreal was the continuous threat associated with the new anti-Semitism. The focus for many who participated in this research was the anti-Jewish sentiment in France and the result of being in a liminal diasporic state of feeling as though they belong elsewhere, possibly in France, to where they want to return, or moving on to other destinations. Multiple centred Jewish and Francophone identities were themes that emerged throughout the interviews. There have been few accounts of the post-1999 French Jewish diaspora and reset- tlement in Canada. There are some scholarly works in the literature, though apart from journalistic reports, there is little information about this diaspora.1 Carol Off’s (2005) CBC documentary entitled One is too Many: Anti-Semitism on the Rise in Eu- rope highlights the new anti-Semitism in France and the outcome of Jews leaving for Canada. The documentary also considers why a very successful segment of Jews would want to leave France, a country in which they have felt relatively secure since the end of the Second World War. This documentary and media reports of French Jews leaving France for destinations such as Canada provided the inspiration for beginning an in-depth case study to investigate why Jews left France and decided to settle in Canada. -

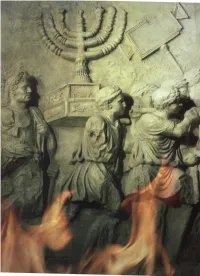

The Struggle to Preserve Judaism 12.1 Introduction in the Last Chapter, You Read About the Origins of Judaism

CHAPTER 4 Roman soldiers destroy theTemple of Jerusalem and carry off sacred treasures. The Struggle to Preserve Judaism 12.1 Introduction In the last chapter, you read about the origins of Judaism. In this chapter, you will discover how Judaism was preserved even after the Hebrews lost their homeland. As you have learned, the Hebrew kingdom split in two after the death of King Solomon. Weakened by this division, the Hebrews were less able to fight off invaders. The northern kingdom of Israel was the first to fall. In 722 B.C.E., the Assyrians conquered Israel. The kingdom's leaders were carried off to Mesopotamia. In 597 B.C.E., the kingdom of Judah was invaded by another Meso- potamian power, Babylon. King Nebuchadrezzar of Babylon laid siege to the city of Jerusalem. The Hebrews fought off the siege until their food ran out. With the people starving, the Babylonians broke through the walls and captured the city. In 586 B.C.E., Nebuchadrezzar burned down Solomon's great Temple of Jerusalem and all the houses in the city. Most of the people of Judah were taken as captives to Babylon. The captivity in Babylon was the begin- ning of the Jewish Diaspora. The word diaspora means "a scattering." Never again would most of the followers of Judaism be together in a single homeland. Yet the Jews, as they came to be known, were able to keep Judaism alive. In this chapter, you will first learn about four important Jewish beliefs. Then you will read about the Jews' struggle to preserve Judaism after they had been forced to settle in many lands. -

Aliyah and the Ingathering of Exiles: Jewish Immigration to Israel

Aliyah and the Ingathering of Exiles: Jewish Immigration to Israel Corinne Cath Thesis Bachelor Cultural Anthropology 2011 Aliyah and the Ingathering of Exiles: Jewish immigration to Israel Aliyah and the Ingathering of Exiles: Jewish Immigration to Israel Thesis Bachelor Cultural Anthropology 2011 Corinne Cath 3337316 C,[email protected] Supervisor: F. Jara-Gomez Aliyah and the Ingathering of Exiles: Jewish immigration to Israel This thesis is dedicated to my grandfather Kees Cath and my grandmother Corinne De Beaufort, whose resilience and wits are an inspiration always. Aliyah and the Ingathering of Exiles: Jewish immigration to Israel Table of Contents Acknowledgments ...................................................................................................................... 4 General Introduction ............................................................................................. 5 1.Theoretical Framework ............................................................................................... 8 Introduction ........................................................................................................ 8 1.1 Anthropology and the Nation-State ........................................................................ 10 The Nation ........................................................................................................ 10 States and Nation-States ................................................................................... 11 Nationalism ...................................................................................................... -

Antisemitism and Jewish Middle Eastern- Americans Theme: Identity

Sample Lesson: Antisemitism and Jewish Middle Eastern- Americans Theme: Identity Disciplinary Area: Asian American and Pacific Islander Studies Ethnic Studies Values and Principles Alignment: 1, 3, 4, 6 Standards Alignment: CA HSS Analysis Skills (9–12): Chronological and Spatial Thinking 1; Historical Interpretation 1, 3, 4 CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.9-10.7 10.4 CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.11-12.7 CCSS.ELA- LITERACY.W.11-12.8 CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.11-12.9 Lesson Purpose and Overview: This lesson introduces students to antisemitism and its manifestations through the lens of Jewish Middle Eastern Americans, also known as Mizrahi and Sephardic Jews, whose contemporary history is defined by recent struggles as targets of discrimination, prejudice and hate crimes in the United States and globally. Students will analyze and research narratives, primary, and secondary sources about Mizrahi Jews. The source analysis contextualizes the experience of Jewish Middle Eastern Americans within the larger framework of systems of power (economic, political, social). Key Terms and Concepts: Mizrahi, antisemitism, indigeneity, ethnicity, prejudice, refugees, diaspora, immigration, intersectionality Lesson Objective (students will be able to...): 1 1. Develop an understanding of Jewish Middle Eastern Americans (who are also referred to as Arab Jews, Mizrahi Jews, Sephardic Jews, and Persian Jews) and differentiate the various identities, nationalities, and subethnicities that make up the Jewish American community. 2. Develop an understanding of contemporary antisemitism and identify how the Jewish Middle Eastern American community today is impacted by prejudice and discrimination against them, as intersectional refugees, immigrants, and racialized Jewish Americans. 3. Students will construct a visual, written, and oral summary of antisemitism in the United States using multiple written and digital texts. -

Jews in the Diaspora: the Bar Kohkva Revolt Submitted By

Jews In The Diaspora: The Bar Kohkva Revolt Submitted by: Jennifer Troy Subject Area: Jews in the Diaspora: Bar Kokhva Revolt Target Age group: Children (ages 9-13) –To use for adults, simply alter the questions to consider. Abstract: The lesson starts out in a cave-like area to emulate the caves used during the revolt. Then explain the history with Hadrian and how he changed his mind after a while. This lesson is to teach the children about the revolt and how they did it. They spent their time digging out caves all over the land of Israel and designing an intricate system so that they were able to get food and water in, as well as get in an out if entrances were sealed off. The students will learn about how the Romans were trying to convert the Jews--thus learning what Hellenists were. This lesson is designed to be a somewhat interactive history lesson, so that they remember it and enjoy it. The objective of this lesson is for the kids to understand what the rebellion was about, why it happened, how it happened and what it felt like to be in their situation. This is also one of the important events recognized by Tisha B'Av and it is important for the children to know it. Materials: -An outdoors setting where you can find a cave-like atmosphere -If find a cave, make sure to bring candles and matches for light in the cave. -Poster board with keywords relating to the era and revolt- if you like to teach with visuals. -

Studying the Bible: the Tanakh and Early Christian Writings

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press NPP eBooks Monographs 2019 Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings Gregory Eiselein Kansas State University Anna Goins Kansas State University Naomi J. Wood Kansas State University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks Part of the Biblical Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Recommended Citation Eiselein, Gregory; Goins, Anna; and Wood, Naomi J., "Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings" (2019). NPP eBooks. 29. https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks/29 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Monographs at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in NPP eBooks by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings Gregory Eiselein, Anna Goins, and Naomi J. Wood Kansas State University Copyright © 2019 Gregory Eiselein, Anna Goins, and Naomi J. Wood New Prairie Press, Kansas State University Libraries Manhattan, Kansas Cover design by Anna Goins Cover image by congerdesign, CC0 https://pixabay.com/photos/book-read-bible-study-notes-write-1156001/ Electronic edition available online at: http://newprairiepress.org/ebooks This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 International (CC-BY NC 4.0) License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Publication of Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings was funded in part by the Kansas State University Open/Alternative Textbook Initiative, which is supported through Student Centered Tuition Enhancement Funds and K-State Libraries. -

Semi-Clandestine Judaism in Early Modern France: European Horizons and Local Varieties of a Domestic Devotion

Chapter 5 Semi-Clandestine Judaism in Early Modern France: European Horizons and Local Varieties of a Domestic Devotion Carsten L. Wilke If historians of the Portuguese Jewish diaspora share a mental map of their subject, this is due in part to a famous text from 1631 that the Amsterdam rabbi Saul Levi Mortera wrote in reply to the questions of a Spanish priest from Rouen. In this unpublished manuscript, Mortera outlines a three-tiered Jewish geography of Europe: he praises those conversos who had left Spain and Portugal and joined Jewish communities; he pities and excuses those who were trapped on the Iberian Peninsula by the Inquisition’s control of emigration; and he severely blames those who had managed to cross the Pyrenean border but were reluctant to officially become Jews, preferring to settle in safe coun- tries where they could officially be Christians and secretly Jews. This last named category on the moralized map of Sephardic residence op- tions was obviously that of the Portuguese merchant colonies in France, the Southern Netherlands, and several Italian cities, where New Christian immi- grants had to conform to public Catholic worship, but were not threatened by inquiries into their private practice. What is remarkable about Mortera’s text is that this region is not described as an intermediary zone between the realms of the Kahal and of the Inquisition, but as an extreme situation sui generis in religious terms. Those who live in countries where emigration is allowed and from where they can leave freely and without any obstacle to any destination of their choice are in total abjection with the Lord and destined to damnation, because they are truly the worshippers of money. -

Israel, Zionism, and Emigration Anxiety

1 Israel, Zionism, and Emigration Anxiety Every Intelligent Israeli understands that the Yerida of Jews from the land of Israel is a national disaster. Almost Holocaust without murder. —Margalit, 2012 n 2012 poet Irit Katz was interviewed in Haaretz upon publication of her Ifirst book,Hibernation , which was written in the United Kingdom. She had left Israel five years earlier. In the interview, the journalist asks Katz how she explains the large number of Israeli emigrants. Katz replies: “I guess they can. It is easier; the discourse of Yordim is no longer there, not as it used to be” (Sela, 2012:14). The journalist then asks Katz if the fact that so many young people are leaving Israel mean Zionism has failed? Katz gives a very interesting answer: “Maybe it’s the success of Zionism. Maybe we became normal and it is allowed to emigrate” (ibid.). In what follows, I wish to explain the cultural context in which this interview takes place. This chapter explores the relationship between Zionism and immigration, as well as the meaning of emigration in the Jewish-Israeli world. Investigating notions of migration under a discourse of failure and success would enable a better understanding of the critique Katz attributes to Zionism. It is not just a simple choice of words, and the question of normality within this context is meaningful. Zionism expressed a dialectical tension between the desire to be normal in the face of anti-Semitism and the desire to retain difference in the face of assimilation (Boyarin, 1997). The question of normality in the Zionist context is not just about the notions of immigration and emigra- tion, aliyah and yerida. -

Theatretalk: (In)Justice

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2020 TheatreTalk: (In)Justice Meghan Baker Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Baker, Meghan, "TheatreTalk: (In)Justice" (2020). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 379. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/379 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Theatre Talk: (In)Justice Creating Critical Thinking and Conversation Through Methods of Performance using Fiddler on the Roof as an example Meghan Baker Advisor: John Bower Theatre, Performance, and Activism Art is inherently political and no art, in my opinion, is better suited to activism than performance. I personally believe that theatre is one of the greatest vehicles for developing critical social change and cultivating conversation around issues of injustice. For me, there is something uniquely captivating about the power of people sharing a space and watching a live performance. It has the potential to be an extremely productive way to communicate a message, while also creating a secure space for audience members to critically engage with the subject or material and step into other people’s stories. Fostering a safe environment for children to participate in this process not only allows them to develop compassion and awareness from an early age, but gives them the opportunity to increase artistic, imaginative, social, and problem-solving skills.