Divrei Torah on the Haggadah 5779

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rewriting the Haggadah: Judaism for Those Who Hold Food Close

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2020 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2020 Rewriting the Haggadah: Judaism for Those Who Hold Food Close Rose Noël Wax Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020 Part of the Food Studies Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Wax, Rose Noël, "Rewriting the Haggadah: Judaism for Those Who Hold Food Close" (2020). Senior Projects Spring 2020. 176. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020/176 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rewriting the Haggadah: Judaism for Those Who Hold Food Close Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Rose Noël Wax Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2020 Acknowledgements Thank you to my parents for teaching me to be strong in my convictions. Thank you to all of the grandparents and great-grandparents I never knew for forging new identities in a country entirely foreign to them. -

Literacy in Medieval Jewish Culture1

Portrayals of Women with Books: Female (Il)literacy in Medieval Jewish Culture1 Katrin Kogman-Appel Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva The thirteenth century saw a new type of Hebrew book, the Passover haggadah (pl. haggadot). Bound together with the general prayer book in the earlier Middle Ages, the haggadah emerged as a separate, independent volume around that time.2 Once the haggadah was born as an individual book, a considerable number of illustrated specimens were created, of which several have come down to us. Dated to the period from approximately 1280 to 1500, these books were produced in various regions of the Iberian peninsula and southern France (Sepharad), the German lands (Ashkenaz), France, and northern Italy. Almost none of these manuscripts contain a colophon, and in most cases it is not known who commissioned them. No illustrated haggadah from the Islamic realm exists, since there the decoration of books normally followed the norms of Islamic culture, where sacred books received only ornamental embellishments. The haggadah is usually a small, thin, handy volume and contains the liturgical text to be recited during the seder, the privately held family ceremony taking place at the eve of Passover. The central theme of the holiday is the retelling of the story of Israel’s departure from Egypt; the precept is to teach it to one’s offspring.3 The haggadah contains the text to fulfill this precept. Hence this is not simply a collection of prayers to accompany a ritual meal; rather, using the 1 book and reading its entire text is the essence of the Passover holiday. -

Haggadah SUPPLEMENT

Haggadah SUPPLEMENT Historical Legal Textual Seder Ritualistic Cultural Artistic [email protected] • [email protected] Seder 1) Joseph Tabory, PhD, JPS Haggadah 2 cups of wine before the meal ; 2 cups of wine after the meal (with texts read over each pair); Hallel on 2nd cup, immediately before meal; more Hallel on 4th cup, immediately after meal; Ha Lachma Anya – wish for Jerusalem in Aramaic - opens the seder; L’Shana HaBa’ah BiYerushalyaim – wish for Jerusalem in Hebrew - closes it; Aramaic passage (Ha Lachma Anya) opens the evening; Aramaic passage (Had Gadya) closes the evening; 4 questions at the beginning of the seder; 13 questions at the end (Ehad Mi Yode‘a); Two litanies in the haggadah: the Dayenu before the meal and Hodu after the meal. 2) Joshua Kulp, PhD, The Origins of the Seder and Haggadah, 2005, p2 Three main forces stimulated the rabbis to develop innovative seder ritual and to generate new, relevant exegeses to the biblical Passover texts: (1) the twin calamities of the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple and the Bar-Kokhba revolt; (2) competition with emerging Christian groups; (3) assimilation of Greco-Roman customs and manners. 2nd Seder 3) David Galenson, PhD, Old Masters and Young Geniuses There have been two very different types of artist in the modern era…I call one of these methods aesthetically motivated experimentation, and the other conceptual execution. Artists who have produced experimental innovations have been motivated by aesthetic criteria: they have aimed at presenting visual perceptions. Their goals are imprecise… means that these artists rarely feel they have succeeded, and their careers are consequently often dominated by the pursuit of a single objective. -

Pesach – Chag Kasher V'sameach

ב''ה CBT: Pesach Essentials Monday, Mar. 27, 2017h Pesach – Chag Kasher v’Sameach Outline & Source Sheet Course Content: In these classes, we are going to learn and 1 Achilah b’Kedusha (Consecrated discuss Kashrut from an Orthodox Consumption) perspective and we will be discussing kashrut 2 Kosher Concepts and Food in terms of CBT’s congregational standards. 3 What is a Kosher kitchen? In developing this course, I have met with 4 Kashering Your Kitchen Rabbi Allouche and asked him about where 5 Common Kosher Kitchen Issues CBT as a community holds. I will take any 6 Cooking for Shabbat v’Yom Tov questions regarding community standards to 7 Pesach – Chag Kasher v’sameach Rabbi and bring an answer back to the class. Pesach – Chag Kasher v’sameach Pesach – The time of our redemption The Events and Observances of Pesach Pesach Kashrut Basics Akiva ben Avraham [email protected] www.meira-akiva.com Page 1 of 9 ב''ה CBT: Pesach Essentials Monday, Mar. 27, 2017h Pesach – Chag Kasher v’Sameach Outline & Source Sheet Pesach – The time of our redemption 1) What does Pesach mean? Exodus 12:14-20 14) This day shall be to you one of remembrance: you shall celebrate it as a festival to the LORD throughout the ages; you shall celebrate it as an institution for all time. 15) Seven days you shall eat unleavened bread; on the very first day you shall remove leaven from your houses, for whoever eats leavened bread from the first day to the seventh day, that person shall be cut off from Israel. -

Jewish Holiday Guide Tu B’ Shvat 1 As Arepresentation Ofthenatural Cycle

Jewish Holiday Guide Tu B’Shvat 15th day of Shvat “…Just as my ancestors planted for me, so I will plant for my children (Talmud Ta’anit 23a).” Tu B’Shvat is a time when we celebrate the New Year for trees. It falls on the 15th of Shvat in the Hebrew calendar and it is a time for us to focus on our ecological responsibilities and the life cycle of renewal. The very first task that was assigned to humans by God was to care for the environment: ‘God took man and put him into the garden to work it and guard 1 it…’ (Genesis 1:15). In Israel, Tu B’shvat is usually celebrated by planting trees and holding the Tu B’shvat seder. Planting trees is a custom that was first held in 1884 in Israel due to the spiritual significance of the land of Israel and the agricultural emphasis that the Zionist brought with them to Israel. The Tu B’shvat seder is formed out of 4 sections for the 4 worlds as the Kabballah says: • The spiritual world of God represented by fire – Atzilut (nobility) • The physical world of human represented by earth – Assiyah (Doing) • The emotional world represented by air – Briyah (Creation) • The philosophical, thoughtful world represented by water – Yetzirah (Making) Each section of the seder also represents one of the four seasons, and mixtures of red and white wine are drunk in different amounts as a representation of the natural cycle. Tu B’ Shvat Tu Purim 14th day of Adar “The Feast of Lots” Purim is one of the most joyous and fun holidays on the Jewish calendar, as it celebrates the story of two heroes, Esther and Mordecai, and how their courage and actions saved the Jewish people living in Persia from execution. -

Haggadah Portions That Are Talmud Quotes Source Sheet by Emanuel Ben-David

Haggadah portions that are Talmud quotes Source Sheet by Emanuel Ben-David We use two Hebrew words to describe the Ritual of the first night of Passover: ,SEDER - which means order; not a command, but order of things. Also - סֵ דֶ ר changing status of a situation from chaos to orderly, organized (like changing one's status from illegal immigrant to legal resident). Haggadah - from the root that means to tell. As a noun, it would be - הֲ ָ ג דַ ה interpreted as A Story. Lets examine how this word is connected to the commandments that order (dictate, not SEDER...) us to tell a story. שמות י״ג:ג׳ Exodus 13:3 (ג) וַיֹּ֨אמֶ ר מֹשֶׁ֜ ה אֶ ל־הָﬠָ֗ ם זָכ֞ וֹר אֶ ת־ ,And Moses said to the people (3) “Remember this day, on which you הַיּ֤וֹם הַזֶּה֙ אֲשֶׁ֨ ר יְצָאתֶ֤ם מִ מִּ צְ רַ֙יִם֙ went free from Egypt, the house of מִ בֵּ ֣ י ת ֲﬠ בָ דִ֔ י ם כִּ֚ י בְּ חֹ֣ זֶק יָ֔ ד הוֹצִ ֧ יא יְהֹוָ ֛ה bondage, how the LORD freed you אֶתְכֶ֖ם מִ זֶּ֑ה וְ ֥לֹא יֵאָכֵ֖ל חָמֵֽ ץ׃ from it with a mighty hand: no leavened bread shall be eaten. שמות י״ג: ח׳ Exodus 13:8 (ח) ְ ו הִ ַ גּ דְ תָּ ֣ לְ בִ נְ �֔ בַּ יּ֥ וֹם הַ ה֖ וּא לֵ אמֹ֑ ר And you shall explain to your (8) בַּ ﬠֲב֣ וּר זֶ֗ ה ﬠָ שָׂ ֤ ה יְ הוָ ה֙ לִ֔ י בְּ צֵ אתִ ֖ י son on that day, ‘It is because of what the LORD did for me when I מִ מִּ צְ רָ ֽ יִ ם ׃ ’.went free from Egypt V'Higad'tah - it is not a simple saying, sounding, verbalizing; it is - ָ ְ ו הִ ַ ג דְ תַ Source Sheet created on Sefaria by Rabbi Emanuel Ben-David 1 telling the story in a way that it is understood and verify that indeed it is. -

Pesach Rabbi Deborah Silver

4607-ZIG-Walking with JEWISH CALENDAR [cover]_Cover 8/17/10 3:47 PM Page 1 The Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies Walking with the Jewish Calendar Edited By Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson ogb hfrsand vhfrsRachel Miriam Safman 4607-ZIG-WALKING WITH JEWISH CALENDAR-P_ZIG-Walking with 8/17/10 3:46 PM Page 79 WHO KNOWS FOUR? THE DEEPER MEANING OF PESACH RABBI DEBORAH SILVER INTRODUCTION h, the Pesach seder! Tablecloths stained with spilled wine, Haggadot brought down from distant closets, the seder Aplate polished up once again. Aren’t we glad to be here? Yet Pesach runs the risk of being rather like Ebenezer Scrooge’s Christmas Past - hung about with pleasant memories that distance rather than include us. In the same way, the seder runs the risk of being on the wrong side of predictable - boring rather than reassuring, sentimental rather than genuinely feeling, complacent rather than inspiring. Perhaps part of the reason for this is that the seder is one of the most consistently observed Jewish practices. Most of us can probably remember seders from our childhood, and there are those of us who might even have the occasion commemorated in photographs or on film. But this is a festival which bears a closer examination. The story of the birth of the Jewish people is permeated with rich layers of meaning. In this essay we will shake out the crumbs, as it were, and see what we can make of the pattern on the tablecloth. To begin with, let’s look at the number of times that we mention the number four at the seder: We drink four cups of wine. -

Passover Resources / Links – 2019 / 5779

PASSOVER RESOURCES / LINKS – 2019 / 5779 HAGGADOT / SEDER PLANNING CHOOSING A HAGGADAH THAT WORKS FOR YOU (two publishers offer advice) http://www.karben.com/haggadahs (Kar-Ben) http://tinyurl.com/jvfpbes (Behrman House) NEW – THE KVELLER HAGGADAH (A SEDER FOR CURIOUS KIDS AND THEIR GROWNUPS) https://www.kveller.com/haggadah/ NEW – PASSOVER HAGGADAH GRAPHIC NOVEL https://www.korenpub.com/koren_en_usd/koren/haggada/passover-haggadah-graphic- novel.html “THE EXODUS: AN EXTRAORDINARY PASSAGE” - free download Passover Seder supplemental text-learning guide from Global Day of Jewish Learning https://www.theglobalday.org/Passover/ “WELCOME TO THE SEDER – A PASSOVER HAGGADAH FOR EVERYONE” www.tinyurl.com/ybohzt6e “HEARING YOUR OWN VOICE” http://ayeka.org.il/publications/hearing-your-own-voice-the-ayeka-haggadah/ “SHARING THE JOURNEY: THE HAGGADAH FOR THE CONTEMPORARY FAMILY” www.tinyurl.com/y8epaocq “A FAMILY HAGGADAH: LARGE-PRINT EDITION” www.tinyurl.com/yck67ron “LET’S MAKE YOUR OWN PASSOVER HAGGADAH TOGETHER” http://haggadot.com “NEXT YEAR IN A JUST WORLD” – Haggadah and Seder readings from the American Jewish World Service / http://tinyurl.com/luenqja HA LACHMA ANYA FOOD & JUSTICE HAGGADAH SUPPLEMENT - Uri L’Tzedek http://utzedek.org/social-justice-torah/uri-ltzedek-publications/pesach-supplement/ “CREATING LIVELY PASSOVER SEDERS: A SOURCEBOOK OF ENGAGING TALES, TEXTS & ACTIVITIES” by David Arnow, Ph.D. - http://tinyurl.com/znro5rj “PASSOVER: THE FAMILY GUIDE TO SPIRITUAL CELEBRATION” by Dr. Ron Wolfson with Joel Lurie Grishaver - https://tinyurl.com/y5lk4frl -

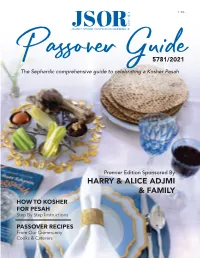

Passover Guide5781/2021 the Sephardic Comprehensive Guide to Celebrating a Kosher Pesah

בס״ד OSHER K JERSEYJSO SHORE ORTHODOX RRABBINATE Passover Guide5781/2021 The Sephardic comprehensive guide to celebrating a Kosher Pesah Premier Edition Sponsored By HARRY & ALICE ADJMI & FAMILY HOW TO KOSHER FOR PESAH Step By Step Instructions PASSOVER RECIPES From Our Community Cooks & Caterers JSOR PASSOVER GUIDE OSHER K JERSEYJSO SHORE ORTHODOX RRABBINATE Table of Contents Rabbinical Board Rabbi Rachamim Aboud Rabbi Edmond Nahum Rabbi Shaul J. Kassin Messages from our Rabbis 10 Kashrut Coordinator Rabbi Isaac Farhi Why is This List Different? 20 Kashrut Administrator Rabbi Hayim Asher Arking Passover Points President 22 Steven Eddie Safdieh Executive Committee Koshering for Pesah Elliot Antebi 24 Edmond Cohen Mark Massry Passover Food Guide Sammy Saka 26 Steven S. Safdieh Richard Setton Jeremy Sultan Quick Pick Medicine List 37 Office Manager Alice Sultan Liquor & Tequila List Women's Auxiliary 38 Joy Betesh Kim Cohen HomeKosher 42 Contributing Writers Rabbi Hayim Asher Arking Rabbi Moshe Arking Pesah Protocol Mrs. Shoshana Farhi 44 Rabbi Meyer Safdieh Richard Setton Recipes 46 Editor Raquele Sasson Pesah FAQ Graphic Design/Marketing 56 Jackie Gindi - JG Graphic Designs Establishments 64 · Visit us on our website www.jsor.org · Follow us on Instagram @jsor_deal · Join our WhatsApp Chat Cover Photo: Sarah Husney | Art Director: Jackie Gindi (via website link) for questions, Table setting: Aimee Hidary and up-to-date information 6 NISSAN 5781 | MARCH 2021 FRIDAY, MARCH 26: Burn Hamets by 11:32am SHABBAT, MARCH 27- EVE OF PESAH: Stop eating Hamets 10:20am. Get rid of any remaining Hamets and recite When Pesah Falls Kal Hamirah by 11:32am SUNDAY, APRIL 4: Holiday over 8:04pm on Saturday Night One can use sold Hamets at 8:45pm Adapted from the Saka Edition of the Yalkut Yosef on Purim 1. -

DEIB Passover.Pub

RADIOLOGY DIVERSITY, EQUITY, INCLUSION & BELONGING PROGRAM March 27th—April 4th Sundown to Sundown The date of Passover changes each year. Passover takes place in early spring during the Hebrew calendar month of Nisan, as prescribed in the book of Exodus. Exodus 12:18 commands that Passover be celebrated, “from the fourteenth day of the month at evening, you shall eat unleavened bread until the twenty-first day of the month at evening.” Why is Passover Celebrated? Passover, or Pesach in Hebrew, is one of the Jewish religion’s most sacred and widely observed holidays. It is centered around the retelling of the Biblical story of Exodus, where God freed the Israelites from slavery in Egypt. The celebration of Passover is prescribed in the book of Exodus in the Old Testament (in Judaism, the first five books of Moses are called the Torah). Often celebrated for eight days (seven in Israel), and in- corporates themes of springtime, a Jewish homeland, fam- ily, remembrance of Jewish history, social justice and free- dom, including recognizing those who are still being op- pressed today. All of these aspects are discussed, if not symbolically represented, during the Passover seder. Seder Meaning: The Hebrew word “seder” translates to “order” or “arrangement” referring to the very specific order of the ritual. The Passover seder is a home ritual blending religious ritu- als, food, song and storytelling. It is traditional for Jewish families to gather on the first night of Passover (first two nights in Orthodox and Conservative communities outside Israel) for a religious feast known as a se- der for the Jewish holiday. -

Archetype and Adaptation: Passover Haggadot from the Stephen P

Archetype and Adaptation: Passover Haggadot from the Stephen P. Durchslag Collection The week-long, springtime Jewish holiday of Pesach, or Passover, is beloved for its symbolic meaning and joyous customs. Passover marks the freeing of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt, a narrative with universal appeal as a paradigm for collective and, according to some traditions, personal liberation. The Haggadah (plural: Haggadot), or “telling,” is the collection of prayers, legends, and stories recited on the eve of Passover. The basic text derives from the biblical instruction to retell the story of the Exodus each year during Passover in conjunction with a ritual meal called the Seder, or “order” (Exodus 13:8). Over the centuries songs and illustrations have been added to engage children, to whom the story was to be told, and some passages are given added prominence when they resonate with contemporary concerns. Illustrations in medieval manuscripts depict scenes from Exodus, the life of Moses, and Jewish Patriarchs. Many of these scenes continue to appear in early printed Haggadot, but the emphasis shifts to passages drawn directly from the text. The Haggadah has shown remarkable stability and flexibility: thousands of editions in all languages testify to its central role in Jewish life and its ability to incorporate new themes and respond to changing conditions. This exhibition is drawn entirely from the private collection of Stephen P. Durchslag, the largest known collection of Haggadot in private hands. “Archetype and Adaptation” explores the enduring influence of early printed Haggadot as well as the ability of modern versions to reflect political and social developments such as the Holocaust, Zionism, gay rights, and feminism. -

Haggadah B'chol Dor Va-Dor (Full)

Haggadah B’chol Dor Va-Dor A Haggadah for all Generations Edited by Rabbi Dr Andrew Goldstein and Rabbi Pete Tobias Designed by Tammy Kustow Dedicated to Rabbi Dr Sidney Brichto 1936-2009 London 2010/5770 iii ii Introduction Acknowledgements Pesach First and foremost, we must acknowledge our debt to Tammy Kustow, whose skill and patience as our designer are worthy of more recognition than will be gained by The origins of Pesach are to be found far back in antiquity, in two separate but these few words. Thanks also to members of Liberal Judaism’s Rabbinic Conference connected spring festivals: a pastoral celebration by shepherds of the lambing who offered suggestions and advice; in particular Rabbis Rachel Benjamin, Janet season, and an agricultural celebration by farmers of the year’s first grain harvest. Burden, David Goldberg and Mark Solomon. Ann and Bob Kirk made valuable This dual connection with nature is reflected in the festival’s two earliest names: suggestions on the content and at the proof reading stage. Chag ha-Pesach – the Festival of the Paschal Lamb, and Chag ha-Matzot – the Festival of Unleavened Bread. Our thanks are also due to the numerous contributors to this Haggadah for their artwork, poetry and other material. Full details can be found in the notes on the Some time after the Exodus from Egypt, which most scholars date in the 13th Liberal Judaism website (www.liberaljudaism.org/haggadah). century BCE, these two nature celebrations were unified in a single festival and their meaning reinterpreted religiously, in the light of the most significant event in Jewish We would particularly like to thank Joe Buchwald Gelles at haggadahsrus.com and history, the Exodus.