BART and Urban Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SFO to San Francisco in 45 Minutes for Only $6.55!* in 30 Minutes for Only $5.35!*

Fold in to the middle; outside right Back Panel Front Panel Fold in to the middle; outside left OAK to San Francisco SFO to San Francisco in 45 minutes for only $6.55!* in 30 minutes for only $5.35!* BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) from OAK is fast, easy and BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) provides one of the world’s inexpensive too! Just take the convenient AirBART shuttle Visitors Guide best airport-to-downtown train services. BART takes you bus from OAK to BART to catch the train to downtown San downtown in 30 minutes for only $5.35 one-way or $10.70 Francisco. The entire trip takes about 45 minutes and costs round trip. It’s the fast, easy, inexpensive way to get to only $6.55 one-way or $13.10 round trip. to BART San Francisco. The AirBART shuttle departs every 15 minutes from the The BART station is located in the SFO International Terminal. 3rd curb across from the terminals. When you get off the It’s only a five minute walk from Terminal Three and a shuttle at the Coliseum BART station, buy a round trip BART 10 minute walk from Terminal One. Both terminals have ticket from the ticket machine. Take the escalator up to the Powell Street-Plaza Entrance connecting walkways to the International Terminal. You can westbound platform and board a San Francisco or Daly City also take the free SFO Airtrain to the BART station. bound train. The BART trip to San Francisco takes about 20 minutes. Terminal 2 (under renovation) Gates 40 - 48 Gates 60 - 67 Terminal 3 Terminal 1 Gates 68 - 90 Gates 20 - 36 P Domestic Want to learn about great deals on concerts, plays, Parking museums and other activities during your visit? Go to www.mybart.org to learn about fantastic special offers for BART customers. -

Transit Information Rockridge Station Oakland

B I R C H C T Transit N Transit Information For more detailed information about BART W E service, please see the BART schedule, BART system map, and other BART information displays in this station. S Claremont Middle Stops OAK GROVE AVE K Rockridge L School San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Schedule Information e ective February 11, 2019 Fares e ective May 26, 2018 A Transit (BART) rail service connects W 79 Drop-off Station the San Francisco Peninsula with See schedules posted throughout this station, or pick These prices include a 50¢ sur- 51B Drop-off 79 Map Key Oakland, Berkeley, Fremont, up a free schedule guide at a BART information kiosk. charge per trip for using magnetic E A quick reference guide to service hours from this stripe tickets. Riders using (Leave bus here to Walnut Creek, Dublin/Pleasanton, and T transfer to 51A) other cities in the East Bay, as well as San station is shown. Clipper® can avoid this surcharge. You Are Here Francisco International Airport (SFO) and U Oakland Oakland International Airport (OAK). Departing from Rockridge Station From Rockridge to: N (stations listed in alphabetical order) 3-Minute Walk 500ft/150m Weekday Saturday Sunday I M I L E S A V E Train Destination Station One Way Round Trip Radius First Last First Last First Last Fare Information e ective January 1, 2016 12th St. Oakland City Center 2.50 5.00 M H I G H W AY 2 4 511 Real-Time Departures Antioch 5:48a 12:49a 6:19a 12:49a 8:29a 12:49a 16th St. -

PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION March 28, 2017 Agenda ID# 15631

STATE OF CALIFORNIA EDMUND G. BROWN JR., Governor PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION 505 VAN NESS AVENUE SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94102 March 28, 2017 Agenda ID# 15631 TO PARTIES TO RESOLUTION ST-203 This is the Resolution of the Safety and Enforcement Division. It will be on the April 27, 2017, Commission Meeting agenda. The Commission may act then, or it may postpone action until later. When the Commission acts on the Resolution, it may adopt all or part of it as written, amend or modify it, or set it aside and prepare its own decision. Only when the Commission acts does the resolution become binding on the parties. Parties may file comments on the Resolution as provided in Article 14 of the Commission’s Rules of Practice and Procedure (Rules), accessible on the Commission’s website at www.cpuc.ca.gov. Pursuant to Rule 14.3, opening comments shall not exceed 15 pages. Late-submitted comments or reply comments will not be considered. An electronic copy of the comments should be submitted to Colleen Sullivan (email: [email protected]). /s/ ELIZAVETA I. MALASHENKO ELIZAVETA I. MALASHENKO, Director Safety and Enforcement Division SUL:vdl Attachment CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I certify that I have by mail this day served a true copy of Draft Resolution ST-203 on all identified parties in this matter as shown on the attached Service List. Dated March 28, 2017, at San Francisco, California. /s/ VIRGINIA D. LAYA Virginia D. Laya NOTICE Parties should notify the Safety Enforcement Division, California Public Utilities Commission, 505 Van Ness Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94102, of any change of address to ensure that they continue to receive documents. -

ACT BART S Ites by Region.Csv TB1 TB6 TB4 TB2 TB3 TB5 TB7

Services Transit Outreach Materials Distribution Light Rail Station Maintenance and Inspection Photography—Capture Metadata and GPS Marketing Follow-Up Programs Service Locations Dallas, Los Angeles, Minneapolis/Saint Paul San Francisco/Oakland Bay Area Our Customer Service Pledge Our pledge is to organize and act with precision to provide you with excellent customer service. We will do all this with all the joy that comes with the morning sun! “I slept and dreamed that life was joy. I awoke and saw that life was service. I acted and behold, service was joy. “Tagore Email: [email protected] Website: URBANMARKETINGCHANNELS.COM Urban Marketing Channel’s services to businesses and organizations in Atlanta, Dallas, San Francisco, Oakland and the Twin Cities metro areas since 1981 have allowed us to develop a specialty client base providing marketing outreach with a focus on transit systems. Some examples of our services include: • Neighborhood demographic analysis • Tailored response and mailing lists • Community event monitoring • Transit site management of information display cases and kiosks • Transit center rider alerts • Community notification of construction and route changes • On-Site Surveys • Enhance photo and list data with geocoding • Photographic services Visit our website (www.urbanmarketingchannels.com) Contact us at [email protected] 612-239-5391 Bay Area Transit Sites (includes BART and AC Transit.) Prepared by Urban Marketing Channels ACT BART S ites by Region.csv TB1 TB6 TB4 TB2 TB3 TB5 TB7 UnSANtit -

Agenda and Packet

SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA RAPID TRANSIT DISTRICT 300 Lakeside Drive, P. O. Box 12688, Oakland, CA 94604-2688 NOTICE OF SPECIAL MEETING AND AGENDA BOND OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE Tuesday, July 16, 2019 9:00 a.m. – 11:00 a.m. COMMITTEE MEMBERS: Marian Breitbart, Michael Day, Leah Edwards, Daren Gee, Michael McGill, Catherine Newman, John Post A Special Meeting of the Bond Oversight Committee will be held on Tuesday, July 16, 2019, at 9:00 a.m. The Meeting will be held in Conference Room 2200, 300 Lakeside Drive, 22nd Floor, Oakland, California. AGENDA 1. Call to Order A. Roll Call 2. Introduction of Committee Members and BART Staff 3. Public Comment on Item 4 Only 4. Annual Report Adoption (For Discussion/Action) 5. Public Comment on Item 6 Only 6. Brown Act Communication Rules Refresher (For Discussion) 7. Adjournment Please refrain from wearing scented products (perfume, cologne, after-shave, etc.) to this meeting, as there may be people in attendance susceptible to environmental illnesses. BART provides service/accommodations upon request to persons with disabilities and individuals who are limited English proficient who wish to address Committee matters. A request must be made within one and five days in advance of Board/Committee meetings, depending on the service requested. Please contact the Office of the District Secretary at (510) 464-6083 for information. Measure rr Bond oversight CoMMittee ANNUAL REPORT June 2019 taBle oF Contents Dear Bay Area residents: letter from the Chairperson 1 renew track 14 Thank you for your interest in the on-going executive summary 2 renew Power infrastructure 16 about us: your Bond oversight repair tunnels and structures 18 efforts to rebuild BART. -

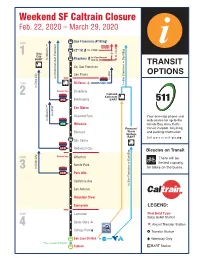

Weekend SF Caltrain Closure Feb

Weekend SF Caltrain Closure Feb. 22, 2020 – March 29, 2020 San Francisco (4th/King) ZONE st nd to 3rd/20th 22 St 8 1 Daly T 9 City to San Bruno/ BART to Mission/1 Bayshore Arleta So. San Francisco TRANSIT San Bruno OPTIONS to Downtown San Francisco to SFO SFO ZONE Millbrae to San Francisco or East Bay to Daly City Weekend Only Broadway 2 Oakland Coliseum 292 Burlingame BART st San Mateo via SFO Hayward Park Your one-stop phone and to Mission/1 web source for up-to-the 398 Hillsdale minute Bay Area traffic, Fremont/ transit, carpool, bicycling Belmont Warm and parking information Springs BART San Carlos ECR Redwood City Bicycles on Transit Weekend Only ZONE Atherton There will be limited capacity Menlo Park 3 to Daly City for bikes on the buses. ECR Palo Alto California Ave to San Francisco or East Bay San Antonio Mountain View Sunnyvale LEGEND: ZONE Lawrence Red Bold Type - Baby Bullet Station Santa Clara 4 Airport Transfer Station College Park ◊ • Transfer Station San Jose Diridon 181 ◊ Weekday Only Free weekend Shuttle Tamien BART Station Caltrain will NOT provide weekend service to San Francisco or 22nd Street stations February 22, 2020 to March 29, 2020. Trains will terminate at Bayshore Station. Free bus service will be available for Caltrain riders from Bayshore Station to 22nd Street and San Francisco stations. Listed below are some transit options that might work better for you. Connect with BART (bart.gov) at the Use SamTrans Bus Service (Limited Millbrae Transit Center Number of Bikes Allowed) Estimated Travel Time (From Millbrae BART From/To Downtown San Francisco Station): Route 292 (samtrans.com/292) • Approx. -

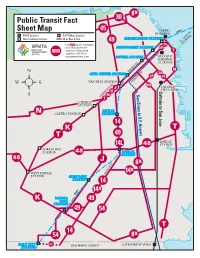

Transit Fact Sheet and Muni Tips With

8x Public Transit Fact 30 Sheet Map 45 FERRY BUILDING BART BART Stations BART/Muni Stations AND AKL GE ID Muni Subway Stations Muni Bus & Rail EMBARCADERO STATION - O F. 49 S. Y BR For route, schedule, 14 BA fare and accessible MONTGOMERY STATION 14x services information T anytime: Call 311 or visit www.sfmta.com POWELL STATION TRANSBAY TERMINAL (AC TRANSIT) N MARKET ST. CIVIC CENTER STATION 30 8x 45 VAN NESS STATION MISSION ST. D x N 14 U CALTRAIN O J R Caltrain to San Jose San to Caltrain 4TH & KING G K ER D SamTrans to S.F. Airport N N U T CHURCH STATION 16TH ST. N CASTRO STATION STATION 14 K T T 49 22ND ST. 14L 48 STATION FOREST HILL STATION 48 24TH ST. STATION 48 J 8x 14x WEST PORTAL MISSION ST. STATION GLEN PARK STATION 14 14x BART BALBOA K PARK 49 STATION 49 54 T 14 54 8x DALY CITY 14L SAN MATEO COUNTY BAYSHORE STATION STATION San Francisco Public Transit Options FACT SHEET AND MUNI ROUTE TIPS Muni bus routes providing alternate, parallel service to BART service within San Francisco are indicated with numbers, while Muni rail lines are indicated with letters. Adult full Muni fare is $2. Youth and Senior/Disabled fare is 75 cents. Exact change or Clipper Cards are required on Muni vehicles; Muni Metro tickets can be purchased at the Metro vend- ing machines in the subway stations for use at subway fare gates. To reach San Francisco International Airport or other peninsula destinations use SamTrans or Caltrain service. -

Smart Parking Management Field Test: a Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) District Parking Demonstration; Final Report Caroline J

CALIFORNIA PATH PROGRAM INSTITUTE OF TRANSPORTATION STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Smart Parking Management Field Test: A Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) District Parking Demonstration; Final Report Caroline J. Rodier, Susan A. Shaheen, Charlene Kemmerer University of California, Berkeley California PATH Research Report UCB-ITS-PRR-2008-5 This work was performed as part of the California PATH Program of the University of California, in cooperation with the State of California Business, Transportation, and Housing Agency, Department of Transportation, and the United States Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the State of California.This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. Final Report for Task Orders 6109 June 2008 ISSN 1055-1425 CALIFORNIA PARTNERS FOR ADVANCED TRANSIT AND HIGHWAYS SMART PARKING MANAGEMENT FIELD TEST: A BAY AREA RAPID TRANSIT (BART) DISTRICT PARKING DEMONSTRATION FINAL REPORT Task Order 6109 Caroline J. Rodier, Ph.D. Senior Researcher, Transportation Sustainability Research Center University of California, Berkeley 1301 S. 46th Street, Bldg. 190; Richmond, CA 94804-4648 510-665-3524 (O); 510-665-2183 (F); [email protected] Susan A. Shaheen, Ph.D. Honda Distinguished Scholar in Transportation, University of California, Davis & Research Director, Transportation Sustainability Research Center University of California, Berkeley 1301 S. 46th Street, Bldg. 190; Richmond, CA 94804-4648 510-665-3483 (O); 510-665-2183 (F); [email protected]; [email protected] and Charlene Kemmerer Research Associate, Transportation Sustainability Research Center University of California, Berkeley 1301 S. -

Bart at Twenty: Land Use and Development Impacts

ffional Development BART@20: Land Use and Development Impacts Robert Cervero with research assistance by Carlos Castellanos, Wicaksono Sarosa, and Kenneth Rich July 1995 University of California at Berkeley - 1 BART@20: Land Use and Development Impacts Robert Cervero with Research Assistance by Carlos Castellanos, Wicaksono Sarosa, and Kenneth Rich This paper was produced with support provided by the U.S. Department of Transportation and the California State Department of Transportation (Caltrans) through the University of California Transportation Center. University of California at Berkeley Institute of Urban and Regional Development Table of Contents ONE: BART at 20: An Analysis of Land Use Impacts 1 1. INTRODUCTION 1 TWO: Research Approach and Data Sources 3 THREE: Employment and Population Changes in BART and Non-BART Areas 6 3.1. Population Changes 6 3.2. Employment Changes 3.3. Population Densities 15 3.4. Employment Densities 15 3.5. Summary 20 FOUR: Land Use Changes Over Time and by Corridor 21 4.1. General Land-Use Trends 23 4.2. Pre-BART versus Post-BART 25 4.3. Early versus Later BART 30 4.4. Trends in Non-Residential Densities 33 4.4. Summary 37 FIVE: Land-Use Changes by Station Classes 38 5.1. Grouping Variables 38 5.2. Classification 38 5.3. Station Classes 41 5.4. Trends in Residential and Non-Residential Growth Among Station Classes 44 5.5. Percent Growth in Early- versus Later-BART Years Among Station Classes 46 5.6. Trends in Non-Residential Densities Among Station Classes 46 SLX: Matched-Pair Comparisons of Land-Use Changes near BART Stations Versus Freeway Interchanges 51 6.1. -

Netsci Transportation Information

The Transportation Information for NetSci 2014 1. SFO to Clark Kerr and Claremont Airport Shuttles from San Francisco International Airport to Clark Kerr and Claremont Hotel Airport shuttles provide door-to-door service. The price is $34 for one person and 15 for additional person. The total occupancy of the shuttle is for 7 people. Reservations are recommended. Bay Porter Express 1-877-467-1800 (Bay Area toll free) • 1-415-467-1800 (outside Bay Area) East Bay Transportation 1-877-526-0304, 1-510-526-0304 Airport Commuter 1-888-876-1777 Taxi Taxi fare to Berkeley will be approximately $78 from the San Francisco airport. http://www.veteranstaxicab.com/ BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) BART is the Bay Area's subway system. The campus is closest to the Downtown Berkeley station on the Richmond line and to the Rockridge station on the Pittsburg/Bay Point line. There is no direct connection to downtown Berkeley from San Francisco on Sundays and evenings. At those times, take the Pittsburg/Bay Point train and transfer to a Richmond train at the 12th Street (Oakland) station (traveling to San Francisco at those times, transfer at MacArthur station). Monday - Friday, 4 a.m. to midnight* Saturday, 6:00 a.m. to midnight* Sunday, 8:00 a.m. to midnight* *In many cases, BART service extends past midnight. Individual station closing times are coordinated with the schedule for the last train, beginning at around midnight. BART trains typically run every 15 minutes on weekdays and every 20 minutes on evenings, weekends and holidays. For exact times, check the following website. -

Smarter Parking at Transit Stations

Smarter Parking at Transit Stations BY SUSAN SHAHEEN AND CHARLENE KEMMERER 27 A C C E S S NUMBER 31, FALL 2007 RANSIT STATIONS , SUCH AS MANY OF THE OUTLYING STATIONS along the BART system in the San Francisco Bay Area, provide parking so riders can easily get to and from the station. At first parking spots at BART stations were free to whoever showed up earliest to park. Then in 2002, BART began offering monthly reservations on some parking spots for a fee, Tso that riders who couldn’t rush out of the house to arrive at the station before anyone else also had the opportunity to park. Commuters without the monthly permits are faced with a dilemma if they want to take BART and can’t get to the station early. Do they risk deviating from their driving commute route to try to find a spot at the station? If they don’t find one, they will have wasted time and gas, and they’d then have to find their way back to their driving route, now a bit later, and reinsert themselves into the stream of traffic. Is there a way for commuters to know whether there are parking spots available? Is there a way for people to guarantee that they can park at the transit station if they exit their driving route? And in the process, is it possible to encourage some drive-alone commuters to park their cars and ride BART? We think so, using what are called “smart parking” systems—broadly defined as the integration of technologies to streamline the parking process. -

Muni Metro Guide 1986

METRO GUIDE INTRODUCTION Welcome to Muni Metro! This brochure introduces you to Muni's light rail system, and offers a full descrip tion of its features. Five lines operate in the Muni Metro. Cars of the J, K, L, M and N lines run in the Market Street subway downtown, and branch off to serve dif ferent neighborhoods of the city. Tunnel portals are located at Duboce Avenue and Church Street and at West Portal. The light rail vehi cles feature high/low steps at center doors. In the subway, these steps remain flush with the car floor and station platforms. For street operation, the steps lower for easy access to the pavement. SUBWAY STATIONS MEZZANINE Muni Metro has nine subway stations: Embarcadero, The mezzanine is the Montgomery, Powell, Civic Center, Van Ness, Church, level immediately below Castro, Forest Hill, and West Portal. the street, where you pay your fare and enter STATION ENTRANCES the Metro system. At Embarcadero, Mont Orange Muni or BART/ gomery, Powell, and Muni signposts mark Civic Center Stations, subway entrances on Muni Metro shares the the street. Near the top mezzanine with BART, of the stairs, brown the Bay Area Rapid Transit system. BART and Muni signs list the different maintain separate station agent booths and faregates. Metro lines which stop Muni booths are marked with orange and BART with below. blue. Change machines may be used by all passen gers. Ticket machines issue BART tickets only. Though BART and Muni share the mezzanine level, they do not share the same platforms andrai/lines. Be sure to choose the right faregates.