Community Organizations Inthe Scioto, Mann, and Havana Hopewellian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

2004 Midwest Archaeological Conference Program

Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 47 2004 Program and Abstracts of the Fiftieth Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Sixty-First Southeastern Archaeological Conference October 20 – 23, 2004 St. Louis Marriott Pavilion Downtown St. Louis, Missouri Edited by Timothy E. Baumann, Lucretia S. Kelly, and John E. Kelly Hosted by Department of Anthropology, Washington University Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri-St. Louis Timothy E. Baumann, Program Chair John E. Kelly and Timothy E. Baumann, Co-Organizers ISSN-0584-410X Floor Plan of the Marriott Hotel First Floor Second Floor ii Preface WELCOME TO ST. LOUIS! This joint conference of the Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Southeastern Archaeological Conference marks the second time that these two prestigious organizations have joined together. The first was ten years ago in Lexington, Kentucky and from all accounts a tremendous success. Having the two groups meet in St. Louis is a first for both groups in the 50 years that the Midwest Conference has been in existence and the 61 years that the Southeastern Archaeological Conference has met since its inaugural meeting in 1938. St. Louis hosted the first Midwestern Conference on Archaeology sponsored by the National Research Council’s Committee on State Archaeological Survey 75 years ago. Parts of the conference were broadcast across the airwaves of KMOX radio, thus reaching a larger audience. Since then St. Louis has been host to two Society for American Archaeology conferences in 1976 and 1993 as well as the Society for Historical Archaeology’s conference in 2004. When we proposed this joint conference three years ago we felt it would serve to again bring people together throughout most of the mid-continent. -

Archaeologist Volume 58 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 58 NO. 1 WINTER 2008 PUBLISHED BY THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OHIO The Archaeological Society of Ohio BACK ISSUES OF OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST Term 1956 thru 1967 out of print Expires A.S.O. OFFICERS 1968 - 1999 $ 2.50 2008 President Rocky Falleti, 5904 South Ave., Youngstown, OH 1951 thru 1955 REPRINTS - sets only $100.00 44512(330)788-1598. 2000 thru 2002 $ 5.00 2003 $ 6.00 2008 Vice President Michael Van Steen, 5303 Wildman Road, Add $0.75 For Each Copy of Any Issue Cedarville, OH 45314 (937) 766-5411. The Archaeology of Ohio, by Robert N. Converse regular $60.00 2008 Immediate Past President John Mocic, Box 170 RD #1, Dilles Author's Edition $75.00 Bottom, OH 43947 (740) 676-1077. Postage, Add $ 5.00 Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are generally 2008 Executive Secretary George Colvin, 220 Darbymoor Drive, out of print but copies are available from time to time. Write to business office Plain City, OH 43064 (614) 879-9825. for prices and availability. 2008 Treasurer Chris Rummel, 6197 Shelba Drive, Galloway, OH ASO CHAPTERS 43119(614)558-3512 Aboriginal Explorers Club 2008 Recording Secretary Cindy Wells, 15001 Sycamore Road, Mt. President: Mark Kline, 1127 Esther Rd., Wellsville, OH 43968 (330) 532-1157 Beau Fleuve Chapter Vernon, OH 43050 (614) 397-4717. President: Richard Sojka, 11253 Broadway, Alden, NY 14004 (716) 681-2229 2008 Webmaster Steven Carpenter, 529 Gray St., Plain City, OH. Blue Jacket Chapter 43064(614)873-5159. President: Ken Sowards, 9201 Hildgefort Rd., Fort Laramie, OH 45845 (937) 295-3764 2010 Editor Robert N. -

Hopewell Archeology: the Newsletter of Hopewell Archeology in the Ohio River Valley Volume 2, Number 2, October 1997

Hopewell Archeology: The Newsletter of Hopewell Archeology in the Ohio River Valley Volume 2, Number 2, October 1997 1. Current Research at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park By Bret J. Ruby, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio Archeological research is an essential activity at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. An active program of field research provides the information necessary to protect and preserve Hopewellian archeological resources. The program also addresses a series of long-standing questions regarding the cultural history and adaptive strategies of Hopewellian populations in the central Scioto region. Presented below are preliminary notices of recent field projects conducted by park personnel with the assistance of the National Park Service's Midwest Archeological Center, Lincoln, Nebraska. These recent efforts are focused on three Hopewellian centers in Ross County. Two of these centers, the Mound City Group and the Hopeton Earthworks, are administered by the National Park Service as units of Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. The third center, the Spruce Hill Works, is privately owned and is being considered for possible inclusion in the park. Research at the Mound City Group Work at the Mound City Group was prompted by plans to install a set of eight new interpretive signs along a trail encircling the mounds and earthworks at the site. Although the Mound City Group has been the focus of archeological investigations for almost 150 years, previous research has focused almost exclusively on the mounds and earthworks themselves (Figure 1), with little attention paid to identifying archeological resources that may lie just outside the earthwork walls. Figure 1. -

62Nd Annual Midwest Archaeological Conference October 4–6, 2018 No T R E Dame Conference Center Mc Kenna Hall

62nd Annual Midwest Archaeological Conference October 4–6, 2018 No t r e Dame Conference Center Mc Kenna Hall Parking ndsp.nd.edu/ parking- and- trafǢc/visitor-guest-parking Visitor parking is available at the following locations: • Morris Inn (valet parking for $10 per day for guests of the hotel, rest aurants, and conference participants. Conference attendees should tell t he valet they are here for t he conference.) • Visitor Lot (paid parking) • Joyce & Compt on Lot s (paid parking) During regular business hours (Monday–Friday, 7a.m.–4p.m.), visitors using paid parking must purchase a permit at a pay st at ion (red arrows on map, credit cards only). The permit must be displayed face up on the driver’s side of the vehicle’s dashboard, so it is visible to parking enforcement staff. Parking is free after working hours and on weekends. Rates range from free (less than 1 hour) to $8 (4 hours or more). Campus Shut t les 2 3 Mc Kenna Hal l Fl oor Pl an Registration Open House Mai n Level Mc Kenna Hall Lobby and Recept ion Thursday, 12 a.m.–5 p.m. Department of Anthropology Friday, 8 a.m.–5 p.m. Saturday, 8 a.m.–1 p.m. 2nd Floor of Corbett Family Hall Informat ion about the campus and its Thursday, 6–8 p.m. amenities is available from any of t he Corbett Family Hall is on the east side of personnel at the desk. Notre Dame Stadium. The second floor houses t he Department of Anthropology, including facilities for archaeology, Book and Vendor Room archaeometry, human osteology, and Mc Kenna Hall 112–114 bioanthropology. -

FREE Trial Issue (PDF)

ANCIENTANCIENTANCIENT AMERICANAMERICANAMERICAN© ArchaeologyArchaeology ofof thethe AmericasAmericas BeforeBefore ColumbusColumbus A Mysterious Discovery Beneath the Serpent’s Head Burrows Cave Marble Stone isIs RecentlyRecently Carved Copper Ingots Manufactured in Louisiana Stonehenge Compared to the Earthworks of the Ohio Burial Mounds of the Upper Mississippi Glozel Tablets Reviewed DDwwaarrffiissmm Ancient Waterways Revealed on Burrows Cave iinn AAnncciieenntt Mapstone MMeessooAAmmeerriiccaa VVooll..uummee 1144 •• IIssssuuee NNuummbbeerr 8899 •• $$77..9955 1993-94 Ancient American Six Issues in Original Format Now Available: 1 thru 6 • AA#1. Petroglyphs of Gorham • AA#2. Burrows Cave: Fraud or Find of the Century • AA#3. Stones of Atlantis • AA#4. Face of Asia • AA#5. Archives of the Past: Stone, Clay, Copper • AA#6. Vikings Any 2 for $30.00 + 2.50 $19.95 ea. plus 2.50 post Windows and MacIntosh Two or more $15.00 ea. 1994-95 Ancient American Six Issues in Original Format Now Available: 7 thru 12 • AA#7. Ruins of Comalcalco • AA#8. Ancient Egyptians Sail to America • AA#9. Inca Stone • AA#10. Treasure of the Moche Lords • AA#11. The Kiva: Gateway for Man • AA#12. Ancient Travelers to the Americas All 3 for $45.00 + 3.00 $19.95 ea. plus 2.50 post Two or more $15.00 ea. Windows and MacIntosh Mystic Symbol Mark of the Michigan Mound Builders The largest archaeological tragedy in the history of the USA. Starting in the 1840’s, over 10,000 artifacts removed from the earth by pioneers clearing the land in Michigan. Stone, Clay and Copper tablets with a multitude of everyday objects, tools and weapons. -

Indiana Archaeology Month 2015 Commemorative Poster

Indiana Archaeology Month 2015 commemorative poster The Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) is pleased to present this special poster celebrating 20 years of a statewide celebration of Indiana archaeology. The poster brings together artifacts from around the state, a number of which were featured on past Archaeology Week and Archaeology Month posters and shirts. The logo in the bottom right is drawn from the image that was on the very first Indiana Archaeology Week poster in 1996. We remember the past, and also look forward to the Indiana Archaeology Months to come! The artifacts are arranged in chronological layers from the most recent at the top, to the oldest at the bottom: 1. Historic amber glass hair stain bottle (upper right) from the Bronnenberg farm at Mounds State Park (Madison County). This type of hair stain was popular from ca. 1900 to 1910. 2. Ceramic sherd (upper left) of Harmonist manufacture (early 19th century) from historic New Harmony (Posey County). 3. Silver trade Lorraine Cross (middle right) with maker’s mark stamp “JS” (Jonas Schindler) on reverse. 18th century, Tippecanoe County. 4. Prehistoric seated fluorite figurine (middle left) from the Angel Site (A.D. 1050 to 1450) (Vanderburgh County). The figurine was recovered in 1940 from Mound F by the WPA crew that worked there doing archaeology over- seen by Glenn A. Black. 5. An unusual incised jar rim sherd from the important Mississippian (late 11th and early 12th centuries) Prather Site (Clark County). 6. Early Archaic St. Charles (8000-6000 B.C.) projectile point (bottom left corner). -

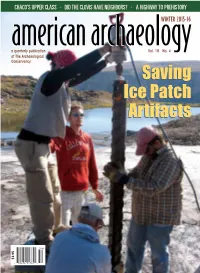

Saving Ice Patch Artifacts Saving Ice Patch Artifacts

CHACO’S UPPER CLASS • DID THE CLOVIS HAVE NEIGHBORS? • A HIGHWAY TO PREHISTORY american archaeologyWINTER 2015-16 americana quarterly publication archaeology Vol. 19 No. 4 of The Archaeological Conservancy SavingSaving IceIce PatchPatch ArtifactsArtifacts $3.95 american archaeologyWINTER 2015-16 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 19 No. 4 COVER FEATURE 12 ARCHAEOLOGY IN THE ICE PATCHES BY TAMARA STEWART Archaeologists are racing to preserve fragile artifacts that are exposed when ice patches melt. 19 THE ROAD TO PREHISTORY BY ELIZABETH LUNDAY A highway-expansion project in Texas led to the discovery of several ancient Caddo sites and raised issues about preservation. 26 CHACO’S UPPER CLASS EE L BY CHARLES C. POLING New research suggests an elite class emerged at RAIG C / Chaco Canyon much earlier than previously thought. AAR NST 32 DID THE CLOVIS PEOPLE HAVE NEIGHBORS? I 12 BY MARCIA HILL GOSSARD Discoveries from the Cooper’s Ferry site indicate that two different cultures inhabited North America 44 new acquisition roughly 13,000 years ago. CONSERVANCY ACQUIRES A PORTION OF MANZANARES PUEBLO IN NEW MEXICO 38 LIFE ON THE NORTHERN FRONTIER Manzanares is one of the sites included in the Galisteo BY WAYNE CURTIS Basin Archaeological Sites Protection Act. Researchers are trying to understand what life was like at an English settlement in southern Maine around 46 new acquisition the turn of the 18th century. DONATION OF TOWN SQUARE BANK MOUND UNITES LOCAL COMMUNITY Various people played a role in the Conservancy’s 19 acquisition of a prehistoric mound. 47 point acquisition A LONG TIME COMING The Conservancy waited for 20 years to acquire T the Dingfelder Circle. -

2013 Program + Abstracts

SUMMARY SCHEDULE MORNING AFTERNOON EVENING Fort Ancient Roundtable Opening Session OHS Reception 8–12 (Marion Rm) Ohio Earthworks, 1–4 Exhibit: Following (Delaware Rm) in Ancient Exhibits Footsteps , 5–7 THURS 12–5 (Morrow Rm) (shuttles begin at 4 at North Entrance) Exhibits Exhibits Student/Professional 8–12 (Morrow Rm) 12–5 (Morrow Rm) Mixer Symposia and Papers Symposia and Papers 5–9 (Barley’s Earthen Enclosures, 8:15– Woodland-Mississippi Underground) 11:45 (Fairfield Rm) Valley, 1:30–3:30 Late Prehist. Oneota, 8:30– (Fairfield Rm) 10:30 (Knox Rm) Late Prehist. -Ohio Valley Historic, 8–11 am (Marion & Michigan, 1:30–5 Rm) (Knox Rm) Late Prehistoric, 10:45–12 Woodland Mounds & (Knox Rm) Earthworks, 1:30–4 Posters (Marion Rm) FRIDAY Midwestern Archaeology, 9– Late Woodland – Ohio 12 (Fayette Rm) Valley, Michigan & MAC Executive Board Meeting Ontario, 3:45-5:00 12–1:30 (Nationwide B Rm) (Fairfield Rm) Posters Midwestern Archaeology, 1:30–4:30 (Fayette Rm) Student Workshop Getting the Job, 4:15–5:30 (Marion Rm) Exhibits Exhibits Reception and Cash 8–12 (Morrow Rm) 12–5 (Morrow Rm) Bar Symposia and Papers Symposia and Papers 5:30–7 (Franklin Ohio Archaeology, 8–11:15 Woodland -Ohio Valley Rm) (Fairfield Rm) and Michigan, 1:30–4 Banquet and Speaker Paleoindian & Archaic, (Fairfield Rm) 7–9 (Franklin Rm) 8:15–10:00 (Knox Rm) RIHA Project, 1:30–3:30 CRM, 9–12 (Marion Rm) (Knox Rm) Aztalan Structure, 10:15– Late Prehistoric -Upper SATURDAY 11:45 (Knox Rm) Mississippi Valley, 1:30– Posters 3:30 (Marion Rm) Angel Mounds, 9–12 Posters (Fayette Rm) Fort Ancient (Guard Site), OAC Business Meeting 1:30–4:30 (Fayette Rm) 11:15–12 (Fairfield Rm) MAC Business Meeting 4:15–5:15 (Fairfield Rm) Hopewell Earthworks Bus Tour 8 am–4 pm (meet at North Entrance of the hotel) SUN ~ 2 ~ TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary Schedule ...................................................................................... -

Discover Illinois Archaeology

Discover Illinois Archaeology ILLINOIS ASSOCIATION FOR ADVANCEMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY ILLINOIS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY Discover Illinois Archaeology Illinois’ rich cultural heritage began more collaborative effort by 18 archaeologists from than 12,000 years ago with the arrival of the across the state, with a major contribution by ancestors of today’s Native Americans. We learn Design Editor Kelvin Sampson. Along with sum- about them through investigations of the remains maries of each cultural period and highlights of they left behind, which range from monumental regional archaeological research, we include a earthworks with large river-valley settlements to short list of internet and print resources. A more a fragment of an ancient stone tool. After the extensive reading list can be found at the Illinois arrival of European explorers in the late 1600s, a Association for Advancement of Archaeology succession of diverse settlers added to our cul- web site www.museum.state.il.us/iaaa/DIA.pdf. tural heritage, leading to our modern urban com- We hope that by reading this summary of munities and the landscape we see today. Ar- Illinois archaeology, visiting a nearby archaeo- chaeological studies allow us to reconstruct past logical site or museum exhibit, and participating environments and ways of life, study the rela- in Illinois Archaeology Awareness Month pro- tionship between people of various cultures, and grams each September, you will become actively investigate how and why cultures rise and fall. engaged in Illinois’ diverse past and DISCOVER DISCOVER ILLINOIS ARCHAEOLOGY, ILLINOIS ARCHAEOLOGY. summarizing Illinois culture history, is truly a Alice Berkson Michael D. Wiant IIILLINOIS AAASSOCIATION FOR CONTENTS AAADVANCEMENT OF INTRODUCTION. -

An Archaeological Survey of the Wabash Valley in Illinois

LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY QF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN 507 '• r CENTRAL CIRCULATION BOOKSTACKS The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its renewal or its return to the library from which it was borrowed on or before the Latest Date stamped below. You may be charged a minimum fee of $75.00 for each lost book. are reason* Thoft, imtfOaHM, and underlining of bck. dismissal from for dtelpltaary action and may result In TO RENEW CML TELEPHONE CENTER, 333-8400 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN APR 2003 MG 1 2 1997 AUG 2 4 2006 AUG 2 3 1999 AUG 13 1999 1ft 07 WO AU6 23 2000 9 10 .\ AUG 242000 Wh^^ie^i^ $$$ae, write new due date below previous due date. 1*162 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/archaeologicalsu10wint Howard D. Winters s AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OFTHE WABASH VALLEYin Illinois mmm* THE 3 1367 . \ Illinois State Museum STATE OF ILLINOIS Otto Kerner, Governor DEPARTMENT OF REGISTRATION AND EDUCATION John C. Watson, Director ILLINOIS STATE MUSEUM Milton D. Thompson, Museum Director REPORTS OF INVESTIGATIONS. No. 10 AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF THE WABASH VALLEY IN ILLINOIS by Howard D. Winters Printed by Authority of the State of Illinois Springfield, Illinois 1967 BOARD OF THE ILLINOIS STATE MUSEUM Everett P. Coleman, M.D., Chairman Coleman Clinic, Canton Myers John C.Watson Albert Vice-President, Myers Bros. Director, Department of Springfield Registration and Education Sol Tax, Ph.D., Secretary William Sylvester White of Anthropology Professor Judge, Circuit Court Dean, University Extension Cook County, Chicago University of Chicago Leland Webber C. -

Ceremonial “Killing” of Hopewell Items Recovered from Redeposit Pits in Mann Mound 3, Posey County, Indiana

CEREMONIAL “KILLING” OF HOPEWELL ITEMS RECOVERED FROM REDEPOSIT PITS IN MANN MOUND 3, POSEY COUNTY, INDIANA A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Sara E. Cole August 2017 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by Sara E. Cole B.A., Indiana University, 2006 M.A., Kent State University, 2017 Approved by Mark F. Seeman , Advisor Mary Ann Raghanti , Chair, Department of Anthropology James L. Blank , Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS……………………………………….…………………………….…iii LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………………….………………..………….v LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………….…………..………vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………..….…viii CHAPTERS I. Those Who “Killed”………………………………………………………..……..1 Introduction………………………………….…………………………………....1 Hopewell…………………………………….…………………………………....2 II. Discussion of the Mann Site……………….……………………………………..8 The Mann Site……………………………………….…………………………....8 History of Mann Site Excavations………………………….………………….…9 Mound 3………………………………………………………….……………...12 Plummets………………………………………………………………………...16 Lithics……………………………………………………………………………21 Bone………………………………………………………………………….….25 Ceramics………………………………………………………………………....27 Galena……………………………………………………………………………28 Other…………………………………………………………………………..…29 III. Hopewell “Killings”………………………………………………...…...............38 Hopewell Practice of “Killing”……………………………………..…...............38 Cases and their Context……………………………………………..…...............39 Mound