Hopewell Conference Final Program and Abstracts.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Further Investigations Into the King George

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Further investigations into the King George Island Mounds site (16LV22) Harry Gene Brignac Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Brignac Jr, Harry Gene, "Further investigations into the King George Island Mounds site (16LV22)" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2720. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2720 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FURTHER INVESTIGATIONS INTO THE KING GEORGE ISLAND MOUNDS SITE (16LV22) A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Geography and Anthropology By Harry Gene Brignac Jr. B.A. Louisiana State University, 2003 May, 2010 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to give thanks to God for surrounding me with the people in my life who have guided and supported me in this and all of my endeavors. I have to express my greatest appreciation to Dr. Rebecca Saunders for her professional guidance during this entire process, and for her inspiration and constant motivation for me to become the best archaeologist I can be. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Understanding Community: Microwear Analysis of Blades at the Mound House Site

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 4-16-2019 Understanding Community: Microwear Analysis of Blades at the Mound House Site Silas Levi Chapman Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, Silas Levi, "Understanding Community: Microwear Analysis of Blades at the Mound House Site" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 1118. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1118 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNDERSTANDING COMMUNITY: MICROWEAR ANALYSIS OF BLADES AT THE MOUND HOUSE SITE SILAS LEVI CHAPMAN 89 Pages Understanding Middle Woodland period sites has been of considerable interest for North American archaeologists since early on in the discipline. Various Middle Woodland period (50 BCE-400CE) cultures participated in shared ideas and behaviors, such as constructing mounds and earthworks and importing exotic materials to make objects for ceremony and for interring with the dead. These shared behaviors and ideas are termed by archaeologists as “Hopewell”. The Mound House site is a floodplain mound group thought to have served as a “ritual aggregation center”, a place for the dispersed Middle Woodland communities to congregate at certain times of year to reinforce their shared identity. Mound House is located in the Lower Illinois River valley within the floodplain of the Illinois River, where there is a concentration of Middle Woodland sites and activity. -

2004 Midwest Archaeological Conference Program

Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 47 2004 Program and Abstracts of the Fiftieth Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Sixty-First Southeastern Archaeological Conference October 20 – 23, 2004 St. Louis Marriott Pavilion Downtown St. Louis, Missouri Edited by Timothy E. Baumann, Lucretia S. Kelly, and John E. Kelly Hosted by Department of Anthropology, Washington University Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri-St. Louis Timothy E. Baumann, Program Chair John E. Kelly and Timothy E. Baumann, Co-Organizers ISSN-0584-410X Floor Plan of the Marriott Hotel First Floor Second Floor ii Preface WELCOME TO ST. LOUIS! This joint conference of the Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Southeastern Archaeological Conference marks the second time that these two prestigious organizations have joined together. The first was ten years ago in Lexington, Kentucky and from all accounts a tremendous success. Having the two groups meet in St. Louis is a first for both groups in the 50 years that the Midwest Conference has been in existence and the 61 years that the Southeastern Archaeological Conference has met since its inaugural meeting in 1938. St. Louis hosted the first Midwestern Conference on Archaeology sponsored by the National Research Council’s Committee on State Archaeological Survey 75 years ago. Parts of the conference were broadcast across the airwaves of KMOX radio, thus reaching a larger audience. Since then St. Louis has been host to two Society for American Archaeology conferences in 1976 and 1993 as well as the Society for Historical Archaeology’s conference in 2004. When we proposed this joint conference three years ago we felt it would serve to again bring people together throughout most of the mid-continent. -

POINT PLEASANT 1774 Prelude to the American Revolution

POINT PLEASANT 1774 Prelude to the American Revolution JOHN F WINKLER ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CAMPAIGN 273 POINT PLEASANT 1774 Prelude to the American Revolution JOHN F WINKLER ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS Series editor Marcus Cowper © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 The strategic situation The Appalachian frontier The Ohio Indians Lord Dunmore’s Virginia CHRONOLOGY 17 OPPOSING COMMANDERS 20 Virginia commanders Indian commanders OPPOSING ARMIES 25 Virginian forces Indian forces Orders of battle OPPOSING PLANS 34 Virginian plans Indian plans THE CAMPAIGN AND BATTLE 38 From Baker’s trading post to Wakatomica From Wakatomica to Point Pleasant The battle of Point Pleasant From Point Pleasant to Fort Gower THE AFTERMATH 89 THE BATTLEFIELD TODAY 93 FURTHER READING 94 INDEX 95 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com 4 British North America in1774 British North NEWFOUNDLAND Lake Superior Quebec QUEBEC ISLAND OF NOVA ST JOHN SCOTIA Montreal Fort Michilimackinac Lake St Lawrence River MASSACHUSETTS Huron Lake Lake Ontario NEW Michigan Fort Niagara HAMPSHIRE Fort Detroit Lake Erie NEW YORK Boston MASSACHUSETTS RHODE ISLAND PENNSYLVANIA New York CONNECTICUT Philadelphia Pittsburgh NEW JERSEY MARYLAND Point Pleasant DELAWARE N St Louis Ohio River VANDALIA KENTUCKY Williamsburg LOUISIANA VIRGINIA ATLANTIC OCEAN NORTH CAROLINA Forts Cities and towns SOUTH Mississippi River CAROLINA Battlefields GEORGIA Political boundary Proposed or disputed area boundary -

Clay Family Is One of the Oldest in This County" Article Was Published 26 Aug

Clay Family Article Clay Family Article, 1950 "Clay Family Is One Of The Oldest In This County" Article was published 26 Aug. 1950 in the 1950 Centennial Edition of the Beckley Post-Herald. Reprinted by permission. The Clay family is one of the oldest in America. Members of this family resided in what is now Raleigh County even before it's foundation 100 years ago and have figured prominently through the years of the county's existence. John Clay, an ancient planter, came to Virginia in 1613, and his wife, Ann, in 1623. It is claimed by some that he came from Wales, but the best authority is that he was English. It is known that he had three sons, whose names, according to some, were Henry, William, and Charles, while others state that he had four sons, Francis, William, Thomas, and Charles. At any rate from the sons of John Clay descended most of the Virginia Clays. There was a Clay family also in Surrey County at an early date, and it is probable that the names of this family in the early records has caused the confusion as to the names of John Clay's children. --Large Land Owner Clay was a large land proprietor in Charles City County. The early colonial records show that he was granted a patent for 1,200 acres on Ward's Creek, fronting on James River, in that part of that county which later became Prince George County - 100 acres to him as an old planter before the government of Sir Thomas Dale, and the other 1,100 acres for the transportation of twenty-two persons. -

Newark Earthworks Center - Ohio State University and World Heritage - Ohio Executive Committee INDIANS and EARTHWORKS THROUGH the AGES “We Are All Related”

Welcoming the Tribes Back to Their Ancestral Lands Marti L. Chaatsmith, Comanche/Choctaw Newark Earthworks Center - Ohio State University and World Heritage - Ohio Executive Committee INDIANS AND EARTHWORKS THROUGH THE AGES “We are all related” Mann 2009 “We are all related” Earthen architecture and mound building was evident throughout the eastern third of North America for millennia. Everyone who lived in the woodlands prior to Removal knew about earthworks, if they weren’t building them. The beautiful, enormous, geometric precision of the Hopewell earthworks were the culmination of the combined brilliance of cultures in the Eastern Woodlands across time and distance. Has this traditional indigenous knowledge persisted in the cultural traditions of contemporary American Indian cultures today? Mann 2009 Each dot represents Indigenous architecture and cultural sites, most built before 1491 Miamisburg Mound is the largest conical burial mound in the USA, built on top of a 100’ bluff, it had a circumference of 830’ People of the Adena Culture built it between 2,800 and 1,800 years ago. 6 Miamisburg, Ohio (Montgomery County) Picture: Copyright: Tom Law, Pangea-Productions. http://pangea-productions.net/ Items found in mounds and trade networks active 2,000 years ago. years 2,000 active networks trade and indicate vast travel Courtesy of CERHAS, Ancient Ohio Trail Inside the 50-acre Octagon at Sunrise 8 11/1/2018 Octagon Earthworks, Newark, OH Indigenous people planned, designed and built the Newark Earthworks (ca. 2000 BCE) to cover an area of 4 square miles (survey map created by Whittlesey, Squier, and Davis, 1837-47) Photo Courtesy of Dan Campbell 10 11/1/2018 Two professors recover tribal knowledge 2,000 years ago, Indigenous people developed specialized knowledge to construct the Octagon Earthworks to observe the complete moon cycle: 8 alignments over a period of 18 years and 219 days (18.6 years) “Geometry and Astronomy in Prehistoric Ohio” Ray Hively and Robert Horn, 1982 Archaeoastronomy (Supplement to Vol. -

State Parks and Early Woodland Cultures

State Parks and Early Woodland Cultures Key Objectives State Parks Featured Students will understand some basic information related to the ■ Mounds State Park www.in.gov/dnr/parklake/2977.htm Adena, Hopewell and early Woodland Indians, and their connec- ■ Falls of the Ohio State Park www.in.gov/dnr/parklake/2984.htm tions to Mounds and Falls of the Ohio state parks. The students will gain insight into the connection between the Adena culture and the Hopewell tradition, and learn how archaeologists have studied artifacts and mounds to understand these cultures. Activity: Standards: Benchmarks: Assessment Tasks: Key Concepts: Mounds Students will research what was import- Artifacts Identify and compare the major early cultures ant to the Adena Indians. The students Tribes Researching SS.4.1.1 that existed in the region that became Indiana will then compile a list of items found in Adena the Past before contact with Europeans. the Adena mounds and compare them to Hopewell items that we use today. Mississippians Identify and describe historic Native American Use computers in a cooperative group groups that lived in Indiana before the time of to create timelines of major events from SS.4.1.2 early European exploration, including ways that the era of the Adena to the rise of the the groups adapted to and interacted with the Hopewell Indians. physical environment. Use computers in a cooperative group Create and interpret timelines that show rela- to create timelines of major events from SS.4.1.15 tionships among people, events and movements the era of the Adena to the rise of the in the history of Indiana. -

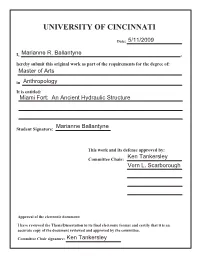

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 5/11/2009 I, Marianne R. Ballantyne , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in Anthropology It is entitled: Miami Fort: An Ancient Hydraulic Structure Marianne Ballantyne Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Ken Tankersley Vern L. Scarborough Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Ken Tankersley Miami Fort: An Ancient Hydraulic Structure A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Anthropology of the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences 2009 Marianne R. Ballantyne B.A., University of Toledo 2007 Committee: Kenneth B. Tankersley, Chair Vernon L. Scarborough ABSTRACT Miami Fort, located in southwestern Ohio, is a multicomponent hilltop earthwork approximately nine kilometers in length. Detailed geological analyses demonstrate that the earthwork was a complex gravity-fed hydraulic structure, which channeled spring waters and surface runoff to sites where indigenous plants and cultigens were grown in a highly fertile but drought prone loess soil. Drill core sampling, x-ray diffractometry, high-resolution magnetic susceptibility analysis, and radiocarbon dating demonstrate that the earthwork was built after the Holocene Climatic Optimum and before the Medieval Warming Period. The results of this study suggest that these and perhaps other southern Ohio hilltop earthworks are hydraulic structures rather than fortifications. -

Archaeologists Solve a 40-Year-Old Mystery? 2 Lay of the Land

INTERPRETING MISSISSIPPIAN ART • CONFRONTING A CONUNDRUM • JEFFERSON’S RETREAT american archaeologyFALL 2005 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 9 No. 3 MesaMesa VVerde’serde’s ANCIENTANCIENT WAWATERWORKSTERWORKS $3.95 Archaeological Tours led by noted scholars Invites You to Journey Back in Time Jordan (14 days) Libya (20 days) Retrace the route of Nabataean traders Tour fabulous classical cities including Leptis with Dr.Joseph A.Greene,Harvard Magna,Sabratha and Cyrene,as well as the Semitic Museum.We’ll explore pre-Islamic World Heritage caravan city Gadames,with ruins and desert castles,and spend a Sri Lanka (18 days) our scholars.The tour ends with a four-day week in and around Petra visiting its Explore one of the first Buddhist adventure viewing prehistoric art amidst tombs and sanctuaries carved out of kingdoms with Prof.Sudharshan the dunes of the Libyan desert. rose-red sandstone. Seneviratne,U.of Peradeniya. Discover magnificent temples and Ancient Capitals palaces,huge stupas and colorful of China (17 days) rituals as we share the roads Study China’s fabled past with Prof. with elephants and walk in Robert Thorp,Washington U., the footsteps of kings. as we journey from Beijing’s Imperial Palace Ethiopia and Eritrea (19 days) and Suzhou’s exquisite Delve into the intriguing history of gardens to Shanghai.We’ll Africa’s oldest empires with Dr. visit ancient shrines,world-class Mattanyah Zohar,Hebrew U.Visit ancient museums,Xian’s terra-cotta Axumite cities,Lalibela’s famous rock-cut warriors and the spectacular churches,Gondar’s medieval castles,and Longman Buddhist grottoes. -

62Nd Annual Midwest Archaeological Conference October 4–6, 2018 No T R E Dame Conference Center Mc Kenna Hall

62nd Annual Midwest Archaeological Conference October 4–6, 2018 No t r e Dame Conference Center Mc Kenna Hall Parking ndsp.nd.edu/ parking- and- trafǢc/visitor-guest-parking Visitor parking is available at the following locations: • Morris Inn (valet parking for $10 per day for guests of the hotel, rest aurants, and conference participants. Conference attendees should tell t he valet they are here for t he conference.) • Visitor Lot (paid parking) • Joyce & Compt on Lot s (paid parking) During regular business hours (Monday–Friday, 7a.m.–4p.m.), visitors using paid parking must purchase a permit at a pay st at ion (red arrows on map, credit cards only). The permit must be displayed face up on the driver’s side of the vehicle’s dashboard, so it is visible to parking enforcement staff. Parking is free after working hours and on weekends. Rates range from free (less than 1 hour) to $8 (4 hours or more). Campus Shut t les 2 3 Mc Kenna Hal l Fl oor Pl an Registration Open House Mai n Level Mc Kenna Hall Lobby and Recept ion Thursday, 12 a.m.–5 p.m. Department of Anthropology Friday, 8 a.m.–5 p.m. Saturday, 8 a.m.–1 p.m. 2nd Floor of Corbett Family Hall Informat ion about the campus and its Thursday, 6–8 p.m. amenities is available from any of t he Corbett Family Hall is on the east side of personnel at the desk. Notre Dame Stadium. The second floor houses t he Department of Anthropology, including facilities for archaeology, Book and Vendor Room archaeometry, human osteology, and Mc Kenna Hall 112–114 bioanthropology. -

Archaeologist Volume 41 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 41 NO. 4 FALL 1991 Published by THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OHIO The Archaeological Society of Ohio MEMBERSHIP AND DUES Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are payable on the first of January as follows: Regular membership $15.00; husband and TERM wife (one copy of publication) $16.00; Life membership $300.00. A.S.O. OFFICERS EXPIRES Subscription to the Ohio Archaeologist, published quarterly, is included President James G. Hovan, 16979 South Meadow Circle, in the membership dues. The Archaeological Society of Ohio is an Strongsville, OH 44136, (216) 238-1799 incorporated non-profit organization. Vice President Larry L. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 BACK ISSUES Exec. Sect. Barbara Motts, 3435 Sciotangy Drive, Columbus, OH 43221, (614) 898-4116 (work) (614) 459-0808 (home) Publications and back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist: Recording Sect. Nancy E. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue Ohio Flint Types, by Robert N. Converse $ 6.00 SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 Ohio Stone Tools, by Robert N. Converse $ 5.00 Treasurer Don F. Potter, 1391 Hootman Drive, Reynoldsburg, Ohio Slate Types, by Robert N. Converse $10.00 OH 43068, (614)861-0673 The Glacial Kame Indians, by Robert N. Converse $15.00 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Dr., Plain City, OH Back issues—black and white—each $ 5.00 43064,(614)873-5471 Back issues—four full color plates—each $ 5.00 Immediate Past Pres. Donald A. Casto, 138 Ann Court, Lancaster, OH 43130, (614) 653-9477 Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are generally out of print but copies are available from time to time.