2017 Indiana Archaeology Journal Vol. 12, No. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RIVERINE EROSION HAZARD AREAS Mapping Feasibility Study

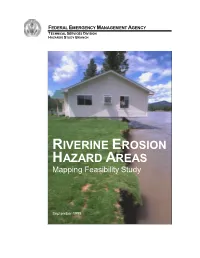

FEDERAL EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT AGENCY TECHNICAL SERVICES DIVISION HAZARDS STUDY BRANCH RIVERINE EROSION HAZARD AREAS Mapping Feasibility Study September 1999 FEDERAL EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT AGENCY TECHNICAL SERVICES DIVISION HAZARDS STUDY BRANCH RIVERINE EROSION HAZARD AREAS Mapping Feasibility Study September 1999 Cover: House hanging 18 feet over the Clark Fork River in Sanders County, Montana, after the river eroded its bank in May 1997. Photograph by Michael Gallacher. Table of Contents Report Preparation........................................................................................xi Acknowledgments.........................................................................................xii Executive Summary......................................................................................xiv 1. Introduction........................................................................................1 1.1. Description of the Problem...........................................................................................................1 1.2. Legislative History.........................................................................................................................1 1.2.1. National Flood Insurance Act (NFIA), 1968 .......................................................................3 1.2.2. Flood Disaster Act of 1973 ...............................................................................................4 1.2.3. Upton-Jones Amendment, 1988........................................................................................4 -

SEAC Bulletin 58.Pdf

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 72ND ANNUAL MEETING NOVEMBER 18-21, 2015 NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE BULLETIN 58 SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE BULLETIN 58 PROCEEDINGS OF THE 72ND ANNUAL MEETING NOVEMBER 18-21, 2015 DOUBLETREE BY HILTON DOWNTOWN NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE Organized by: Kevin E. Smith, Aaron Deter-Wolf, Phillip Hodge, Shannon Hodge, Sarah Levithol, Michael C. Moore, and Tanya M. Peres Hosted by: Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Middle Tennessee State University Division of Archaeology, Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation Office of Social and Cultural Resources, Tennessee Department of Transportation iii Cover: Sellars Mississippian Ancestral Pair. Left: McClung Museum of Natural History and Culture; Right: John C. Waggoner, Jr. Photographs by David H. Dye Printing of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 58 – 2015 Funded by Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, Authorization No. 327420, 750 copies. This public document was promulgated at a cost of $4.08 per copy. October 2015. Pursuant to the State of Tennessee’s Policy of non-discrimination, the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation does not discriminate on the basis of race, sex, religion, color, national or ethnic origin, age, disability, or military service in its policies, or in the admission or access to, or treatment or employment in its programs, services or activities. Equal Employment Opportunity/Affirmative Action inquiries or complaints should be directed to the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, EEO/AA Coordinator, Office of General Counsel, 312 Rosa L. Parks Avenue, 2nd floor, William R. Snodgrass Tennessee Tower, Nashville, TN 37243, 1-888-867-7455. ADA inquiries or complaints should be directed to the ADA Coordinator, Human Resources Division, 312 Rosa L. -

Hard Labor, Donations Transforming White Station High's Tough Courtyard

Public Records & Notices Monitoring local real estate since 1968 View a complete day’s public records Subscribe Presented by and notices today for our at memphisdailynews.com. free report www.chandlerreports.com Wednesday, May 12, 2021 MemphisDailyNews.com Vol. 136 | No. 57 Rack–50¢/Delivery–39¢ Pristex’s heart for medical community starts with family ties to St. Jude CHRISTIN YATES over the city, especially in the hand sanitizer,” Latasha Harris, services that Medical District in- $32.2 million in medical supplies Courtesy of The Daily Memphian Medical District — Shelby Coun- program manager for the Mem- stitutions procure from Memphis and services with local companies The early days of the pandemic ty’s health care epicenter — were phis Medical District Collabora- area businesses. — a 26% increase from what they saw shortages of health care es- scrambling for medical-related tive’s (MMDC) Buy Local initia- Some of the Medical District’s would normally spend. “Our Buy sentials from personal protective supplies. tive, said. anchor institutions include St. Local work is usually focused on equipment (PPE) to disinfectant “It put us in a position where The Buy Local program was Jude Children’s Research Hospital non-medical spend because there wipes, surgical gowns and many we started looking for suppliers launched in 2014 to increase and Regional One Health. In 2020, other products. Institutions all making germicidal wipes and the amount of local goods and the anchor institutions spent PRISTEX CONTINUED ON P2 per 15-second increment to make the holes wide and deep enough for a newly planted tree to thrive Hard labor, donations transforming in the packed soil. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Timescale Dependence in River Channel Migration Measurements

TIMESCALE DEPENDENCE IN RIVER CHANNEL MIGRATION MEASUREMENTS Abstract: Accurately measuring river meander migration over time is critical for sediment budgets and understanding how rivers respond to changes in hydrology or sediment supply. However, estimates of meander migration rates or streambank contributions to sediment budgets using repeat aerial imagery, maps, or topographic data will be underestimated without proper accounting for channel reversal. Furthermore, comparing channel planform adjustment measured over dissimilar timescales are biased because shortand long-term measurements are disproportionately affected by temporary rate variability, long-term hiatuses, and channel reversals. We evaluate the role of timescale dependence for the Root River, a single threaded meandering sand- and gravel-bedded river in southeastern Minnesota, USA, with 76 years of aerial photographs spanning an era of landscape changes that have drastically altered flows. Empirical data and results from a statistical river migration model both confirm a temporal measurement-scale dependence, illustrated by systematic underestimations (2–15% at 50 years) and convergence of migration rates measured over sufficiently long timescales (> 40 years). Frequency of channel reversals exerts primary control on measurement bias for longer time intervals by erasing the record of observable migration. We conclude that using long-term measurements of channel migration for sediment remobilization projections, streambank contributions to sediment budgets, sediment flux estimates, and perceptions of fluvial change will necessarily underestimate such calculations. Introduction Fundamental concepts and motivations Measuring river meander migration rates from historical aerial images is useful for developing a predictive understanding of channel and floodplain evolution (Lauer & Parker, 2008; Crosato, 2009; Braudrick et al., 2009; Parker et al., 2011), bedrock incision and strath terrace formation (C. -

Understanding Community: Microwear Analysis of Blades at the Mound House Site

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 4-16-2019 Understanding Community: Microwear Analysis of Blades at the Mound House Site Silas Levi Chapman Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, Silas Levi, "Understanding Community: Microwear Analysis of Blades at the Mound House Site" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 1118. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1118 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNDERSTANDING COMMUNITY: MICROWEAR ANALYSIS OF BLADES AT THE MOUND HOUSE SITE SILAS LEVI CHAPMAN 89 Pages Understanding Middle Woodland period sites has been of considerable interest for North American archaeologists since early on in the discipline. Various Middle Woodland period (50 BCE-400CE) cultures participated in shared ideas and behaviors, such as constructing mounds and earthworks and importing exotic materials to make objects for ceremony and for interring with the dead. These shared behaviors and ideas are termed by archaeologists as “Hopewell”. The Mound House site is a floodplain mound group thought to have served as a “ritual aggregation center”, a place for the dispersed Middle Woodland communities to congregate at certain times of year to reinforce their shared identity. Mound House is located in the Lower Illinois River valley within the floodplain of the Illinois River, where there is a concentration of Middle Woodland sites and activity. -

2004 Midwest Archaeological Conference Program

Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 47 2004 Program and Abstracts of the Fiftieth Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Sixty-First Southeastern Archaeological Conference October 20 – 23, 2004 St. Louis Marriott Pavilion Downtown St. Louis, Missouri Edited by Timothy E. Baumann, Lucretia S. Kelly, and John E. Kelly Hosted by Department of Anthropology, Washington University Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri-St. Louis Timothy E. Baumann, Program Chair John E. Kelly and Timothy E. Baumann, Co-Organizers ISSN-0584-410X Floor Plan of the Marriott Hotel First Floor Second Floor ii Preface WELCOME TO ST. LOUIS! This joint conference of the Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Southeastern Archaeological Conference marks the second time that these two prestigious organizations have joined together. The first was ten years ago in Lexington, Kentucky and from all accounts a tremendous success. Having the two groups meet in St. Louis is a first for both groups in the 50 years that the Midwest Conference has been in existence and the 61 years that the Southeastern Archaeological Conference has met since its inaugural meeting in 1938. St. Louis hosted the first Midwestern Conference on Archaeology sponsored by the National Research Council’s Committee on State Archaeological Survey 75 years ago. Parts of the conference were broadcast across the airwaves of KMOX radio, thus reaching a larger audience. Since then St. Louis has been host to two Society for American Archaeology conferences in 1976 and 1993 as well as the Society for Historical Archaeology’s conference in 2004. When we proposed this joint conference three years ago we felt it would serve to again bring people together throughout most of the mid-continent. -

A Microdebitage Analysis of the Winterville Mounds Site (22WS500)

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Fall 2017 A Microdebitage Analysis of the Winterville Mounds Site (22WS500) Stephanie Leigh-Ann Guest University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Guest, Stephanie Leigh-Ann, "A Microdebitage Analysis of the Winterville Mounds Site (22WS500)" (2017). Master's Theses. 315. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/315 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MICRODEBITAGE ANALYSIS OF THE WINTERVILLE MOUNDS SITE (22WS500) by Stephanie Leigh-Ann Guest A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Letters, and the Department of Anthropology and Sociology at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2017 A MICRODEBITAGE ANALYSIS OF THE WINTERVILLE MOUNDS SITE (22WS500) by Stephanie Leigh-Ann Guest August 2017 Approved by: ________________________________________________ Dr. Homer E. Jackson, Committee Chair Professor, Anthropology and Sociology ________________________________________________ Dr. Marie E. Danforth, Committee Member Professor, Anthropology and Sociology ________________________________________________ -

State Parks and Early Woodland Cultures

State Parks and Early Woodland Cultures Key Objectives State Parks Featured Students will understand some basic information related to the ■ Mounds State Park www.in.gov/dnr/parklake/2977.htm Adena, Hopewell and early Woodland Indians, and their connec- ■ Falls of the Ohio State Park www.in.gov/dnr/parklake/2984.htm tions to Mounds and Falls of the Ohio state parks. The students will gain insight into the connection between the Adena culture and the Hopewell tradition, and learn how archaeologists have studied artifacts and mounds to understand these cultures. Activity: Standards: Benchmarks: Assessment Tasks: Key Concepts: Mounds Students will research what was import- Artifacts Identify and compare the major early cultures ant to the Adena Indians. The students Tribes Researching SS.4.1.1 that existed in the region that became Indiana will then compile a list of items found in Adena the Past before contact with Europeans. the Adena mounds and compare them to Hopewell items that we use today. Mississippians Identify and describe historic Native American Use computers in a cooperative group groups that lived in Indiana before the time of to create timelines of major events from SS.4.1.2 early European exploration, including ways that the era of the Adena to the rise of the the groups adapted to and interacted with the Hopewell Indians. physical environment. Use computers in a cooperative group Create and interpret timelines that show rela- to create timelines of major events from SS.4.1.15 tionships among people, events and movements the era of the Adena to the rise of the in the history of Indiana. -

Indiana Archaeology

INDIANA ARCHAEOLOGY Volume 5 Number 2 2010/2011 Indiana Department of Natural Resources Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Indiana Department of Natural Resources Robert E. Carter, Jr., Director and State Historic Preservation Officer Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) James A. Glass, Ph.D., Director and Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer DHPA Archaeology Staff James R. Jones III, Ph.D., State Archaeologist Amy L. Johnson Cathy L. Draeger-Williams Cathy A. Carson Wade T. Tharp Editors James R. Jones III, Ph.D., State Archaeologist Amy L. Johnson, Senior Archaeologist and Archaeology Outreach Coordinator Cathy A. Carson, Records Check Coordinator Publication Layout: Amy L. Johnson Additional acknowledgments: The editors wish to thank the authors of the submitted articles, as well as all of those who participated in, and contributed to, the archaeological projects which are highlighted. Cover design: The images which are featured on the cover are from several of the individual articles included in this journal. Mission Statement: The Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology promotes the conservation of Indiana’s cultural resources through public education efforts, financial incentives including several grant and tax credit programs, and the administration of state and federally mandated legislation. 2 For further information contact: Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology 402 W. Washington Street, Room W274 Indianapolis, Indiana 46204-2739 Phone: 317/232-1646 Email: [email protected] www.IN.gov/dnr/historic 2010/2011 3 Indiana Archaeology Volume 5 Number 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Authors of articles were responsible for ensuring that proper permission for the use of any images in their articles was obtained. -

Indiana Archaeology

INDIANA ARCHAEOLOGY Volume 6 Number 1 2011 Indiana Department of Natural Resources Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Indiana Department of Natural Resources Robert E. Carter, Jr., Director and State Historic Preservation Officer Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) James A. Glass, Ph.D., Director and Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer DHPA Archaeology Staff James R. Jones III, Ph.D., State Archaeologist Amy L. Johnson, Senior Archaeologist and Archaeology Outreach Coordinator Cathy L. Draeger-Williams, Archaeologist Wade T. Tharp, Archaeologist Rachel A. Sharkey, Records Check Coordinator Editors James R. Jones III, Ph.D. Amy L. Johnson Cathy A. Carson Editorial Assistance: Cathy Draeger-Williams Publication Layout: Amy L. Johnson Additional acknowledgments: The editors wish to thank the authors of the submitted articles, as well as all of those who participated in, and contributed to, the archaeological projects which are highlighted. The U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service is gratefully acknow- ledged for their support of Indiana archaeological research as well as this volume. Cover design: The images which are featured on the cover are from several of the individual articles included in this journal. This publication has been funded in part by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service‘s Historic Preservation Fund administered by the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. In addition, the projects discussed in several of the articles received federal financial assistance from the Historic Preservation Fund Program for the identification, protection, and/or rehabilitation of historic properties and cultural resources in the State of Indiana. -

62Nd Annual Midwest Archaeological Conference October 4–6, 2018 No T R E Dame Conference Center Mc Kenna Hall

62nd Annual Midwest Archaeological Conference October 4–6, 2018 No t r e Dame Conference Center Mc Kenna Hall Parking ndsp.nd.edu/ parking- and- trafǢc/visitor-guest-parking Visitor parking is available at the following locations: • Morris Inn (valet parking for $10 per day for guests of the hotel, rest aurants, and conference participants. Conference attendees should tell t he valet they are here for t he conference.) • Visitor Lot (paid parking) • Joyce & Compt on Lot s (paid parking) During regular business hours (Monday–Friday, 7a.m.–4p.m.), visitors using paid parking must purchase a permit at a pay st at ion (red arrows on map, credit cards only). The permit must be displayed face up on the driver’s side of the vehicle’s dashboard, so it is visible to parking enforcement staff. Parking is free after working hours and on weekends. Rates range from free (less than 1 hour) to $8 (4 hours or more). Campus Shut t les 2 3 Mc Kenna Hal l Fl oor Pl an Registration Open House Mai n Level Mc Kenna Hall Lobby and Recept ion Thursday, 12 a.m.–5 p.m. Department of Anthropology Friday, 8 a.m.–5 p.m. Saturday, 8 a.m.–1 p.m. 2nd Floor of Corbett Family Hall Informat ion about the campus and its Thursday, 6–8 p.m. amenities is available from any of t he Corbett Family Hall is on the east side of personnel at the desk. Notre Dame Stadium. The second floor houses t he Department of Anthropology, including facilities for archaeology, Book and Vendor Room archaeometry, human osteology, and Mc Kenna Hall 112–114 bioanthropology.