Canterbury Museum 71

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communicating Culture

Communicating Culture National Digital Forum 2014 Otago Museum Sarjeant Transition Project Graham Turbott 1914–2014 Kaitiaki Hui February 2015 February Contents Museums Aotearoa EDs Quarter EDs Quarter 3 Te Tari o Ngã Whare Taonga o te Motu Communicating Culture is the theme for our MA15 conference in Dunedin While in the vicinity, I visited Pompallier Mission this May. Some of our contributors for this MAQ have addressed this in Russell. This is another example of a heritage site Kaitiaki Hui 4 Is New Zealand’s independent peak professional organisation for museums directly, such as Maddy Jones and Jamie Bell, the two National Digital that has undergone substantial change. Heritage and those who work in, or have an interest in, museums. Members include Forum delegates that Museums Aotearoa sponsored. Digital is changing New Zealand has uncovered its intriguing history Behind the Scenes 5 museums, public art galleries, historical societies, science centres, people who nearly every aspect of communicating culture – not only our visitors' access in its sympathetic and understated restoration, work within these institutions and individuals connected or associated with to cultural information, but also what happens back-of-house to provide that and knowledgeable and friendly guides help My Favourite Thing 6 arts, culture and heritage in New Zealand. Our vision is to raise the profile, access. The Dowse Wikipedia project is an interesting example. to interpret it for visitors. Also on my travels, I strengthen the preformance and increase the value of museums and galleries enjoyed a wander around Headland sculpture on Dowse Wikipedia Project 7 to their stakeholders and the community As well as digital projects, there are many other ways of communicating the gulf. -

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1955-1958

THE COMMONWEALTH TRANS-ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955-1958 HOW THE CROSSING OF ANTARCTICA MOVED NEW ZEALAND TO RECOGNISE ITS ANTARCTIC HERITAGE AND TAKE AN EQUAL PLACE AMONG ANTARCTIC NATIONS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree PhD - Doctor of Philosophy (Antarctic Studies – History) University of Canterbury Gateway Antarctica Stephen Walter Hicks 2015 Statement of Authority & Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Elements of material covered in Chapter 4 and 5 have been published in: Electronic version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume00,(0), pp.1-12, (2011), Cambridge University Press, 2011. Print version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume 49, Issue 1, pp. 50-61, Cambridge University Press, 2013 Signature of Candidate ________________________________ Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................. -

The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886

The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886 Sascha Nolden, Simon Nathan & Esme Mildenhall Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H November 2013 Published by the Geoscience Society of New Zealand Inc, 2013 Information on the Society and its publications is given at www.gsnz.org.nz © Copyright Simon Nathan & Sascha Nolden, 2013 Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H ISBN 978-1-877480-29-4 ISSN 2230-4495 (Online) ISSN 2230-4487 (Print) We gratefully acknowledge financial assistance from the Brian Mason Scientific and Technical Trust which has provided financial support for this project. This document is available as a PDF file that can be downloaded from the Geoscience Society website at: http://www.gsnz.org.nz/information/misc-series-i-49.html Bibliographic Reference Nolden, S.; Nathan, S.; Mildenhall, E. 2013: The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886. Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H. 219 pages. The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886 CONTENTS Introduction 3 The Sumner Cave controversy Sources of the Haast-Hooker correspondence Transcription and presentation of the letters Acknowledgements References Calendar of Letters 8 Transcriptions of the Haast-Hooker letters 12 Appendix 1: Undated letter (fragment), ca 1867 208 Appendix 2: Obituary for Sir Julius von Haast 209 Appendix 3: Biographical register of names mentioned in the correspondence 213 Figures Figure 1: Photographs -

Changing Attitudes and Perceptions of Artists Towards the New Zealand

University ofCanterbury Dept. of Geography HA� LIBRARY CH&ISTCHUIICH, � University of Canterbury CHANGING ATTITUDES AND PERCEPTIONS OF ARTISTS TOW ARDS THE NEW ZEALAND MOUNTAIN LANDSCAPE by Katrina Jane Askew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts m Geography Christchurch, New Zealand February 1995 "I go to the mountains, to get High" Anonymous Abstract The purpose of this study is to explore the changing attitudes and perceptions of artists and settlers towards the New Zealand mountain landscape from the period of colonisation to 1950. When European colonists first anived in New Zealand, they brought with them old world values that shaped their attitudes to nature and thus the mountains of this country. Tracing the development of mountain topophilia in landscape painting, highlighted that the perceptions settlers adopted on arrival differed greatly from those of their homeland. In effect, the love of European mountain scenery was not transposed onto their new environment. It was not until the 1880s that a more sympathetic outlook towards mountains developed. This led to the greater depiction of mountains and their eventual adoption into New Zealanders identification with the land. An analysis of paintings housed in the Art Galleries of the South Island provided evidence that this eventually led to the development of a collective consciousness as to the ideal mountain landscape. ll Acknowledgements The production of this thesis would not have been possible but for the assistance of a great number of people. The first person I must thank is Dr. Peter Perry who supervised this research. -

+Tuhinga 27-2016 Vi:Layout 1

27 2016 2016 TUHINGA Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa The journal of scholarship and mätauranga Number 27, 2016 Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa is a peer-reviewed publication, published annually by Te Papa Press PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand TE PAPA ® is the trademark of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Te Papa Press is an imprint of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Tuhinga is available online at www.tepapa.govt.nz/tuhinga It supersedes the following publications: Museum of New Zealand Records (1171-6908); National Museum of New Zealand Records (0110-943X); Dominion Museum Records; Dominion Museum Records in Ethnology. Editorial board: Catherine Cradwick (editorial co-ordinator), Claudia Orange, Stephanie Gibson, Patrick Brownsey, Athol McCredie, Sean Mallon, Amber Aranui, Martin Lewis, Hannah Newport-Watson (Acting Manager, Te Papa Press) ISSN 1173-4337 All papers © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa 2016 Published June 2016 For permission to reproduce any part of this issue, please contact the editorial co-ordinator,Tuhinga, PO Box 467, Wellington. Cover design by Tim Hansen Typesetting by Afineline Digital imaging by Jeremy Glyde Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Number 27, 2016 Contents A partnership approach to repatriation: building the bridge from both sides 1 Te Herekiekie Herewini and June Jones Mäori fishhooks at the Pitt Rivers Museum: comments and corrections 10 Jeremy Coote Response to ‘Mäori fishhooks at the Pitt Rivers Museum: comments 20 and corrections’ Chris D. -

The Establishment of the Canterbury Society of Arts

New Zealand Journal of History, 44, 2 (2010) The Establishment of the Canterbury Society of Arts FORMING THE TASTE, JUDGEMENT AND IDENTITY OF A PROVINCE, 1850–1880 HISTORIES OF NEW ZEALAND ART have commonly portrayed art societies as conservative institutions, predominantly concerned with educating public taste and developing civic art collections that pandered to popular academic British painting. In his discussion of Canterbury’s cultural development, for example, Jonathan Mane-Wheoki commented that the founding of the Canterbury Society of Arts (CSA) in 1880 formalized the enduring presence of the English art establishment in the province.1 Similarly, Michael Dunn has observed that the model for the establishment of New Zealand art societies in the late nineteenth century was the Royal Academy, London, even though ‘they were never able to attain the same prestige or social significance as the Royal Academy had in its heyday’.2 As organizations that appeared to perpetuate the Academy’s example, art societies have served as a convenient, reactionary target for those historians who have contrasted art societies’ long-standing conservatism with the struggle to establish an emerging national identity in the twentieth century. Gordon Brown, for example, maintained that the development of painting within New Zealand during the 1920s and 1930s was restrained by the societies’ influence, ‘as they increasingly failed to comprehend the changing values entering the arts’.3 The establishment of the CSA in St Michael’s schoolroom in Christchurch on 30 June 1880, though, was more than a simple desire by an ambitious colonial township to imitate the cultural and educational institutions of Great Britain and Europe. -

Julius Haast Towards a New Appreciation of His Life And

JULIUS HAAST TOWARDS A NEW APPRECIATION OF HIS LIFE AND WORK __________________________________ A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History in the University of Canterbury by Mark Edward Caudel University of Canterbury 2007 _______ Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................... i List of Plates and Figures ...................................................................................... ii Abstract................................................................................................................. iii Chapter 1: Introduction ........................................................................................ 1 Chapter 2: Who Was Julius Haast? ...................................................................... 10 Chapter 3: Julius Haast in New Zealand: An Explanation.................................... 26 Chapter 4: Julius Haast and the Philosophical Institute of Canterbury .................. 44 Chapter 5: Julius Haast’s Museum ....................................................................... 57 Chapter 6: The Significance of Julius Haast ......................................................... 77 Chapter 7: Conclusion.......................................................................................... 86 Bibliography ......................................................................................................... 89 Appendices .......................................................................................................... -

Bill Ceevee 2014

curriculum vitae, William F. Martin Institutional address: Home address: Institut für Botanik III Rilkestrasse 13 Heinrich Heine-Universität Düsseldorf D-41469 Neuss Universitätsstraße 1 Germany D-40225 Düsseldorf Germany e-mail: [email protected] Tel. +49-211-811-3011 Date of birth : 16.02.57 in Bethesda, Maryland, USA Familial status : Married, four children Nationality : USA University degree : 1981-1985, Technische Universität Hannover, Germany: Biology Diplom thesis : 1985, Institut für Botanik, TU Hannover with Rüdiger Cerff: Botany PhD thesis : 1985-1988, Max-Planck-Institut für Züchtungsforschung, Cologne, with Heinz Saedler; degree conferred by the University of Cologne: Genetics Postdoc : 1988-1989, Max-Planck-Institut für Züchtungsforschung, Cologne Postdoc : 1989-1999, Institut für Genetik, Technische Universität Braunschweig Habilitation : 1992, TU Braunschweig, Germany, venia legendi for the field of Botany Full professor : 1999-2011 for "Ecological Plant Physiology" (C4), Universität Düsseldorf : 2011- for "Molecular Evolution" (C4), Universität Düsseldorf Honours 2013- Visiting Professor, Instituto de Tecnologia Química e Biológica, Oeiras, Portugal 2012 Elected Member of EMBO (European Molecular Biology Organisation) 2010- Science Advisory Committe, Helmholz Alliance Planetry Evoution and Life 2008 Elected Member of the Nordrhein-Westfälische Akademie der Wissenschaften 2007-2012 Selection Committee for the Heinz-Maier-Leibnitz Prize of the DFG 2006 Elected Fellow of the American Academy for Microbiology 2006-2009 Julius von -

Rich Man, Poor Man, Environmentalist, Thief

Rich man, poor man, environmentalist, thief Biographies of Canterbury personalities written for the Millennium and for the 150th anniversary of the Canterbury Settlement Richard L N Greenaway Cover illustration: RB Owen at front of R T Stewart’s Avon River sweeper, late 1920s. First published in 2000 by Christchurch City Libraries, PO Box 1466, Christchurch, New Zealand Website: library.christchurch.org.nz All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from Christchurch City Libraries. ISBN 0 908868 22 7 Designed by Jenny Drummond, Christchurch City Libraries Printed by The Caxton Press, Christchurch For Daisy, Jan and Richard jr Contents Maria Thomson 7 George Vennell and other Avon personalities 11 Frederick Richardson Fuller 17 James Speight 23 Augustus Florance 29 Allan Hopkins 35 Sali Mahomet 41 Richard Bedward Owen 45 Preface Unsung heroines was Canterbury Public Library’s (now Genealogical friends, Rona Hayles and Margaret Reid, found Christchurch City Libraries) contribution to Women’s overseas information at the Family History Centre of the Suffrage Year in 1994. This year, for the Millennium and 150th Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. Professional anniversary of the founding of the Canterbury Settlement, researchers Valerie Marshall in Christchurch and Jane we have produced Rich man, poor man, environmentalist, thief. Smallfield in Dunedin showed themselves skilled in the use In both works I have endeavoured to highlight the lives of of the archive holdings of Land Information New Zealand. -

Tuhinga 25: 1–15 Copyright © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2014)

25 2014 TUHINGA Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa The journal of scholarship and mätauranga Number 25, 2014 Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa is a peer-reviewed publication, published annually by the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand Tuhinga is available online at www.tepapa.govt.nz/tuhinga It supersedes the following publications: Museum of New Zealand Records (1171-6908); National Museum of New Zealand Records (0110-943X); Dominion Museum Records; Dominion Museum Records in Ethnology. Editorial board: Ricardo Palma (editorial co-ordinator), Stephanie Gibson, Patrick Brownsey, Athol McCredie, Sean Mallon, Claire Murdoch (Publisher, Te Papa Press). ISSN 1173-4337 All papers © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa 2014 Published June 2014 For permission to reproduce any part of this issue, please contact the editorial co-ordinator, Tuhinga, PO Box 467, Wellington Cover design by Tim Hansen Typesetting by Afineline Digital imaging by Jeremy Glyde PO Box 467 Wellington Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Number 25, 2014 Contents Domestic expenditure of the Hector family in the early 1870s 1 Simon Nathan, Judith Nathan and Rowan Burns Ko Tïtokowaru: te poupou rangatira 16 Tïtokowaru: a carved panel of the Taranaki leader Hokimate P. Harwood Legal protection of New Zealand’s indigenous terrestrial fauna – 25 an historical review Colin M. Miskelly Tuhinga 25: 1–15 Copyright © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2014) Domestic expenditure of the Hector family in the early 1870s Simon Nathan,* Judith Nathan* and Rowan Burns * 2a Moir Street, Mt Victoria, Wellington 6011 ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: Analysis of a large bundle of family accounts has yielded information on the lifestyle of James and Georgiana Hector in the early 1870s, when they lived in Museum House next door to the Colonial Museum in Wellington. -

Auckland Like Many Other Lay Enthusiasts, He Made Considerable

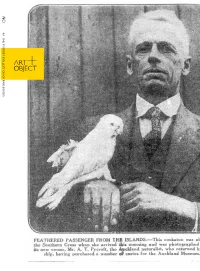

49 THE PYCROFT COLLECTION OF RARE BOOKS Arthur Thomas Pycroft ART + OBJECT (1875–1971) 3 Abbey Street Arthur Pycroft was the “essential gentleman amateur”. Newton Auckland Like many other lay enthusiasts, he made considerable PO Box 68 345 contributions as a naturalist, scholar, historian and Newton conservationist. Auckland 1145 He was educated at the Church of England Grammar Telephone: +64 9 354 4646 School in Parnell, Auckland’s first grammar school, where his Freephone: 0 800 80 60 01 father Henry Thomas Pycroft a Greek and Hebrew scholar Facsimile: +64 9 354 4645 was the headmaster between 1883 and 1886. The family [email protected] lived in the headmaster’s residence now known as “Kinder www.artandobject.co.nz House”. He then went on to Auckland Grammar School. On leaving school he joined the Auckland Institute in 1896, remaining a member Previous spread: for 75 years, becoming President in 1935 and serving on the Council for over 40 years. Lots, clockwise from top left: 515 Throughout this time he collaborated as a respected colleague with New Zealand’s (map), 521, 315, 313, 513, 507, foremost men of science, naturalists and museum directors of his era. 512, 510, 514, 518, 522, 520, 516, 519, 517 From an early age he developed a “hands on” approach to all his interests and corresponded with other experts including Sir Walter Buller regarding his rediscovery Rear cover: of the Little Black Shag and other species which were later included in Buller’s 1905 Lot 11 Supplement. New Zealand’s many off shore islands fascinated him and in the summer of 1903-04 he spent nearly six weeks on Taranga (Hen Island), the first of several visits. -

'Thinking from a Place Called London': the Metropolis and Colonial

‘Thinking from a place called London’: The Metropolis and Colonial Culture, 1837-1907 FELICITY BARNES In April 1907, at the Colonial Conference in London, the premiers of the white self-governing colonies met with members of the imperial government to reconcile two apparently conflicting objectives: to gain greater acknowledgement of their de facto political autonomy, and commitment to strengthening imperial unity.1 The outcomes of this conference tend to be cast in constitutional and political terms, but this process also renegotiated the cultural boundaries of empire. The white settler colonies sought to clarify their position within the empire, by, on the one hand, asserting equal status with Britain, and, on the other, emphasizing the distinction between themselves and the dependent colonies.2 In doing so they invoked and reinforced a hierarchical version of empire. This hierarchy, underpinned by ideas of separation and similarity, would be expressed vividly in the conference’s outcomes, first in the rejection of the term ‘colonial’ as a name for future conferences. These were redesignated, inaccurately, as ‘imperial’, not ‘colonial’, elevating their status as it narrowed their participation.3 ‘Imperial’ might be metropolitan, but ‘colonial’ was always peripheral. Whilst the first Colonial Conference, held in 1887, had included Crown colonies along with the self-governing kinds,4 20 years later the former were no longer invited, and India, or, more precisely, the India Office and its officials, was only a marginal presence.5 As wider participation declined, imperial government involvement increased. From 1907 the conference was to be chaired by the British prime minister. This pattern was repeated in changes to the Colonial Office itself.