The White Horse Press Full Citation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communicating Culture

Communicating Culture National Digital Forum 2014 Otago Museum Sarjeant Transition Project Graham Turbott 1914–2014 Kaitiaki Hui February 2015 February Contents Museums Aotearoa EDs Quarter EDs Quarter 3 Te Tari o Ngã Whare Taonga o te Motu Communicating Culture is the theme for our MA15 conference in Dunedin While in the vicinity, I visited Pompallier Mission this May. Some of our contributors for this MAQ have addressed this in Russell. This is another example of a heritage site Kaitiaki Hui 4 Is New Zealand’s independent peak professional organisation for museums directly, such as Maddy Jones and Jamie Bell, the two National Digital that has undergone substantial change. Heritage and those who work in, or have an interest in, museums. Members include Forum delegates that Museums Aotearoa sponsored. Digital is changing New Zealand has uncovered its intriguing history Behind the Scenes 5 museums, public art galleries, historical societies, science centres, people who nearly every aspect of communicating culture – not only our visitors' access in its sympathetic and understated restoration, work within these institutions and individuals connected or associated with to cultural information, but also what happens back-of-house to provide that and knowledgeable and friendly guides help My Favourite Thing 6 arts, culture and heritage in New Zealand. Our vision is to raise the profile, access. The Dowse Wikipedia project is an interesting example. to interpret it for visitors. Also on my travels, I strengthen the preformance and increase the value of museums and galleries enjoyed a wander around Headland sculpture on Dowse Wikipedia Project 7 to their stakeholders and the community As well as digital projects, there are many other ways of communicating the gulf. -

Rethinking Arboreal Heritage for Twenty-First-Century Aotearoa New Zealand

NATURAL MONUMENTS: RETHINKING ARBOREAL HERITAGE FOR TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND Susette Goldsmith A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2018 ABSTRACT The twenty-first century is imposing significant challenges on nature in general with the arrival of climate change, and on arboreal heritage in particular through pressures for building expansion. This thesis examines the notion of tree heritage in Aotearoa New Zealand at this current point in time and questions what it is, how it comes about, and what values, meanings and understandings and human and non-human forces are at its heart. While the acknowledgement of arboreal heritage can be regarded as the duty of all New Zealanders, its maintenance and protection are most often perceived to be the responsibility of local authorities and heritage practitioners. This study questions the validity of the evaluation methods currently employed in the tree heritage listing process, tree listing itself, and the efficacy of tree protection provisions. The thesis presents a multiple case study of discrete sites of arboreal heritage that are all associated with a single native tree species—karaka (Corynocarpus laevigatus). The focus of the case studies is not on the trees themselves, however, but on the ways in which the tree sites fill the heritage roles required of them entailing an examination of the complicated networks of trees, people, events, organisations, policies and politics situated within the case studies, and within arboreal heritage itself. Accordingly, the thesis adopts a critical theoretical perspective, informed by various interpretations of Actor Network Theory and Assemblage Theory, and takes a ‘counter-’approach to the authorised heritage discourse introducing a new notion of an ‘unauthorised arboreal heritage discourse’. -

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1955-1958

THE COMMONWEALTH TRANS-ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955-1958 HOW THE CROSSING OF ANTARCTICA MOVED NEW ZEALAND TO RECOGNISE ITS ANTARCTIC HERITAGE AND TAKE AN EQUAL PLACE AMONG ANTARCTIC NATIONS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree PhD - Doctor of Philosophy (Antarctic Studies – History) University of Canterbury Gateway Antarctica Stephen Walter Hicks 2015 Statement of Authority & Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Elements of material covered in Chapter 4 and 5 have been published in: Electronic version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume00,(0), pp.1-12, (2011), Cambridge University Press, 2011. Print version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume 49, Issue 1, pp. 50-61, Cambridge University Press, 2013 Signature of Candidate ________________________________ Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................. -

Forest & Bird Annual Report 2013

Forest & Bird New Zealand’s reputation as 100% Pure has long been the cornerstone of our national identity and international selling point. But over the last few years, we’ve witnessed the highlights increasing erosion of our natural treasures and the realisation that 100% Pure New Zealand is not 100% true. New Zealanders have borne attacks on their national parks from mining, greater land intensification and the continual deterioration of our lakes and rivers. And in 2012, the threats to our environment escalated as we witnessed moves to wrench out the heart of the Resource Management Act. The good news is that thanks to the passion and commitment of staff, members and supporters, Forest & Bird generated positive changes that will benefit the environment for generations to come. This year we celebrated victories after lengthy court battles over the wild Mokihinui River, West Coast wetlands and Whakatane’s Kohi Point. We were also the ‘voice for nature’ on collaborative working groups and mapping a sustainable future for New Zealand’s waterways and the Mackenzie Country. Our voice was heard by politicians, councils, industry bodies, community groups and the wider public. This behind-the- scenes role laid the groundwork for better, long-term environmental gains. With 80,000 supporters across 50 branches, we also made a huge contribution on the ground. Forest & Bird members rolled up their sleeves to plant over 200,000 plants this year, survey birds, propagate native seedlings, write submissions, hold public meetings, and set and monitor over 10,000 predator traps. We also spoke to the next generation through our Kiwi Conservation Club. -

+Tuhinga 27-2016 Vi:Layout 1

27 2016 2016 TUHINGA Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa The journal of scholarship and mätauranga Number 27, 2016 Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa is a peer-reviewed publication, published annually by Te Papa Press PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand TE PAPA ® is the trademark of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Te Papa Press is an imprint of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Tuhinga is available online at www.tepapa.govt.nz/tuhinga It supersedes the following publications: Museum of New Zealand Records (1171-6908); National Museum of New Zealand Records (0110-943X); Dominion Museum Records; Dominion Museum Records in Ethnology. Editorial board: Catherine Cradwick (editorial co-ordinator), Claudia Orange, Stephanie Gibson, Patrick Brownsey, Athol McCredie, Sean Mallon, Amber Aranui, Martin Lewis, Hannah Newport-Watson (Acting Manager, Te Papa Press) ISSN 1173-4337 All papers © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa 2016 Published June 2016 For permission to reproduce any part of this issue, please contact the editorial co-ordinator,Tuhinga, PO Box 467, Wellington. Cover design by Tim Hansen Typesetting by Afineline Digital imaging by Jeremy Glyde Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Number 27, 2016 Contents A partnership approach to repatriation: building the bridge from both sides 1 Te Herekiekie Herewini and June Jones Mäori fishhooks at the Pitt Rivers Museum: comments and corrections 10 Jeremy Coote Response to ‘Mäori fishhooks at the Pitt Rivers Museum: comments 20 and corrections’ Chris D. -

Distributions of New Zealand Birds on Real and Virtual Islands

JARED M. DIAMOND 37 Department of Physiology, University of California Medical School, Los Angeles, California 90024, USA DISTRIBUTIONS OF NEW ZEALAND BIRDS ON REAL AND VIRTUAL ISLANDS Summary: This paper considers how habitat geometry affects New Zealand bird distributions on land-bridge islands, oceanic islands, and forest patches. The data base consists of distributions of 60 native land and freshwater bird species on 31 islands. A theoretical section examines how species incidences should vary with factors such as population density, island area, and dispersal ability, in two cases: immigration possible or impossible. New Zealand bird species are divided into water-crossers and non-crossers on the basis of six types of evidence. Overwater colonists of New Zealand from Australia tend to evolve into non-crossers through becoming flightless or else acquiring a fear of flying over water. The number of land-bridge islands occupied per species increases with abundance and is greater for water-crossers than for non-crossers, as expected theoretically. Non-crossers are virtually restricted to large land-bridge islands. The ability to occupy small islands correlates with abundance. Some absences of species from particular islands are due to man- caused extinctions, unfulfilled habitat requirements, or lack of foster hosts. However, many absences have no such explanation and simply represent extinctions that could not be (or have not yet been) reversed by immigrations. Extinctions of native forest species due to forest fragmentation on Banks Peninsula have especially befallen non-crossers, uncommon species, and species with large area requirements. In forest fragments throughout New Zealand the distributions and area requirements of species reflect their population density and dispersal ability. -

Highlights Forest & Bird Fighting for Nature Can Be an Uphill Battle During an Economic Recession

highlights Forest & Bird Fighting for nature can be an uphill battle during an economic recession. The government’s purse strings draw tighter and investment in our natural resources is too often seen as an unaffordable luxury. Cutbacks at the Department of Conservation put added pressure on the environment and the duty fell to groups like Forest & Bird to step up. Despite the challenging climate, Forest & Bird grew in fortitude as New Zealand’s largest independent voice for nature. Our membership and wider support base increased and we continued to advocate strongly by engaging with policy makers, community groups and playing a part on numerous forums. We were quick to challenge through the courts, actions that threatened our unique landscapes and wildlife, especially on the West Coast’s Denniston Plateau and Mokihinui River. We took on the fishing industry and pushed for greater sustainability and better protection of our marine creatures and seabirds. We joined the collaborative negotiations to stop intensive farm development in the Mackenzie Country. Our members remain the lifeblood of the Society and the value of their passion, dedication and commitment to conservation cannot be overestimated. It is their work that ensures Forest & Bird’s core objectives are realised in communities around the country. More and more New Zealanders are choosing to support Forest & Bird. The battle for conservation may not be easy. But with 70,000 supporters and a strong, credible voice reaching all corners of New Zealand we remain steadfast in our commitment to protecting and preserving our natural treasures Annual Report For the year to 29 February 2012 Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society of New Zealand Inc. -

Your Voice for Nature Tō Reo Mō Te Ao Tūroa

© Rob Brown / Hedgehoghouse.com Brown © Rob YOUR VOICE FOR NATURE TŌ REO MŌ TE AO TŪROA 20 ANNUAL REPORT 18 TE PŪRONGO Ā-TAU YOU ARE A VOICE FOR NATURE HE REO KOE MŌ TE AO TŪROA Thank you for your support of Forest & Bird. Over the past financial year, we have been busy defending nature on a number of fronts, and we certainly have plenty to share in this Annual Report. We celebrated 14 important legal We worked to make sure decision- wins for the environment during 2018. makers understood the devastating For example, working in partnership impacts on nature of the current with the Bay of Plenty’s Motiti Rohe climate crisis. We lobbied hard for Moana Trust, we secured a landmark a strong Zero Carbon Act, gave High Court ruling that means regional evidence at the Environment Select councils anywhere in Aotearoa Committee, and secured thousands of New Zealand can use the Resource submissions on our website in support Management Act to establish coastal of legislation committing New Zealand marine protected areas. to being carbon neutral by 2050. Last year also saw a big boost for In every corner of Aotearoa, our conservation on land, with government members and supporters continue funding for the Department of to actively maintain our natural world, Conservation returning to levels not protect threatened species, and speak seen for a decade. We are proud of up for nature in their communities. our role in helping secure this win, While the work of Forest & Bird which places DOC fair and square flourishes, there’s still plenty more back at the frontline, defending nature. -

Tuhinga 25: 1–15 Copyright © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2014)

25 2014 TUHINGA Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa The journal of scholarship and mätauranga Number 25, 2014 Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa is a peer-reviewed publication, published annually by the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand Tuhinga is available online at www.tepapa.govt.nz/tuhinga It supersedes the following publications: Museum of New Zealand Records (1171-6908); National Museum of New Zealand Records (0110-943X); Dominion Museum Records; Dominion Museum Records in Ethnology. Editorial board: Ricardo Palma (editorial co-ordinator), Stephanie Gibson, Patrick Brownsey, Athol McCredie, Sean Mallon, Claire Murdoch (Publisher, Te Papa Press). ISSN 1173-4337 All papers © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa 2014 Published June 2014 For permission to reproduce any part of this issue, please contact the editorial co-ordinator, Tuhinga, PO Box 467, Wellington Cover design by Tim Hansen Typesetting by Afineline Digital imaging by Jeremy Glyde PO Box 467 Wellington Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Number 25, 2014 Contents Domestic expenditure of the Hector family in the early 1870s 1 Simon Nathan, Judith Nathan and Rowan Burns Ko Tïtokowaru: te poupou rangatira 16 Tïtokowaru: a carved panel of the Taranaki leader Hokimate P. Harwood Legal protection of New Zealand’s indigenous terrestrial fauna – 25 an historical review Colin M. Miskelly Tuhinga 25: 1–15 Copyright © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2014) Domestic expenditure of the Hector family in the early 1870s Simon Nathan,* Judith Nathan* and Rowan Burns * 2a Moir Street, Mt Victoria, Wellington 6011 ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: Analysis of a large bundle of family accounts has yielded information on the lifestyle of James and Georgiana Hector in the early 1870s, when they lived in Museum House next door to the Colonial Museum in Wellington. -

Auckland Like Many Other Lay Enthusiasts, He Made Considerable

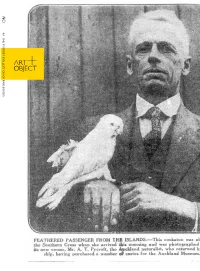

49 THE PYCROFT COLLECTION OF RARE BOOKS Arthur Thomas Pycroft ART + OBJECT (1875–1971) 3 Abbey Street Arthur Pycroft was the “essential gentleman amateur”. Newton Auckland Like many other lay enthusiasts, he made considerable PO Box 68 345 contributions as a naturalist, scholar, historian and Newton conservationist. Auckland 1145 He was educated at the Church of England Grammar Telephone: +64 9 354 4646 School in Parnell, Auckland’s first grammar school, where his Freephone: 0 800 80 60 01 father Henry Thomas Pycroft a Greek and Hebrew scholar Facsimile: +64 9 354 4645 was the headmaster between 1883 and 1886. The family [email protected] lived in the headmaster’s residence now known as “Kinder www.artandobject.co.nz House”. He then went on to Auckland Grammar School. On leaving school he joined the Auckland Institute in 1896, remaining a member Previous spread: for 75 years, becoming President in 1935 and serving on the Council for over 40 years. Lots, clockwise from top left: 515 Throughout this time he collaborated as a respected colleague with New Zealand’s (map), 521, 315, 313, 513, 507, foremost men of science, naturalists and museum directors of his era. 512, 510, 514, 518, 522, 520, 516, 519, 517 From an early age he developed a “hands on” approach to all his interests and corresponded with other experts including Sir Walter Buller regarding his rediscovery Rear cover: of the Little Black Shag and other species which were later included in Buller’s 1905 Lot 11 Supplement. New Zealand’s many off shore islands fascinated him and in the summer of 1903-04 he spent nearly six weeks on Taranga (Hen Island), the first of several visits. -

Botanical Society of Otago Newsletter Number 36 Feb - March 2003

Botanical Society of Otago Newsletter Number 36 Feb - March 2003 Hebejeebia trifiila BSO Meetings and Field Trips 7 March, Fri. 12:00 - 2:30 pm. BSO BBQ to welcome new botany/ecology students and new BSO members. Meet at the front lawn, Botany House Annexe, 479 Great King Street (across the road from the main Botany Building). Sausage sandwiches and juice SI each. AU BSO members welcome! 12 March 2003, Wed. 5.30 pm. BSO Annual General Meeting. Drinks, nibbles and chat followed by a short meeting to elect a chairman and committee for 2003. Then, guest speaker Kelvin Lloyd will give one of his fabulous slide shows on The Botanical Trumpet. More tantalising glimpses of untracked wilderness. Meet in the Zoology Annexe Seminar Room, Gt King St, back behind the car park between Dental School and Zoology Dept. Bring a gold coin donation towards costs 15 March, Sat. 9.30 am. Full day field trip to Mt Watkin/ Hikaroroa with Robyn Bridges. A cross-country walk to a landform of interest both botanically and geologically speaking. The prominent bump on the horizon, on the left as you head north past the Karitane turnoff, is a volcanic hill 'standing alone in a schist landscape' Botanical species of interest include, Copromsma virescens, Fuchsia perscandens and Gingidia montana. Bring all-weather gear, stout footwear, food, drink and money for transport. Meet in the Dept of Botany Car Park, 464 Great King St, to car pool. Passengers pay driver 8c/km. Read WildDunedin by Neville Peat & Brian Patrick for more interesting details about Mt Watkin. -

Forest & Bird Annual Report 2014

Annual Report For the year to 28 February 2014 Forest & Bird highlights 2013 was a landmark year as Forest & Bird members has a unique blend of national and local focus, doing celebrated the 90th birthday with events around the on-the-ground conservation work and speaking up for country, focusing on local milestones and the work nature in our cities and rural communities, and engaging done by long-standing volunteers. It was an opportunity wha¯nau from children to grandparents. Our diversity is to reflect on an extraordinary range of achievements our strength. during the nine decades since Captain Val Sanderson We are looking to the future, identifying the most critical and a former prime minister, Sir Thomas Mackenzie, threats to nature of invasive pests, climate change and launched the Society at a public meeting in Wellington unsustainable development, and working on meaningful in 1923. solutions in which all New Zealanders can play a On the national stage, our successes during the part. Our vision is for a predator-free New Zealand, past 90 years have included several new national landscape-scale conservation and an ecologically Captain Val Sanderson parks and marine reserves, saving Lake Manapo¯uri, sustainable economy, engaging in partnerships with iwi protecting West Coast and central North Island native and others who share our values. forests from logging, the purchase of Maud Island in The Society’s guiding principles and structure are under the Marlborough Sounds and Mangere Island in the review and we are reshaping the organisation so it has Chathams as wildlife sanctuaries, the creation of the the strength to meet the societal, scientific, commercial Department of Conservation and the protection of many and technological demands of coming years.