LITHUANIA Mapping Digital Media: Lithuania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nproliferation Review Is Unable to Russia & Republics Nuclear Industry, 5/25/94, P

Nuclear Developments 15 NEWLY-INDEPENDENT ST ATES 3/17/94 ARMENIA WITH THE FORMER A secondary agreement is signed in Mos- SOVIET UNION ARMENIA cow between Russian First Deputy Minis- ter Oleg Soskovets and Armenian Prime 4/4/94 Minister Grant Bagratyan regarding the The Romanian newspaper Romania Libera renovations and reactivation of the Metsamor publishes allegations that the former Soviet INTERNAL DEVELOPMENTS nuclear power plant. The agreement will Union may have used a seismic weapon create an intergovernmental committee for called the Elipton to trigger a major earth- 2/94 the renovation project. Minatom and quake in Armenia. According to the article, Armenia’s Minister of Energy and Fuel Re- Gosatomnadzor will represent Russia on the U.S. military intelligence experts noted that sources Miron Sheshmanali reports that it committee, while the Armenian Energy the earthquake occurred at a time when the is essential for the rebuilding of Armenia’s Ministry and the Armenian State Director- Soviet authorities would have wanted to power generating industry to restart the ate for the Supervision of Nuclear Energy destroy Armenia's nuclear industry in or- nuclear power plant. will represent Armenia. Russia will pro- der to ensure the republic's continued de- Novosti, 5/2/94; in Russia & CIS Today, 5/2/94, vide nuclear fuel, engineering services, as- No. 0315, p. 9 (11154). pendence on the USSR. sistance in the development of a nuclear Oana Stanciulescu, Romania Libera (Bucharest), 4/ power management structure in Armenia, 4/94, p.1; in FBIS-SOV-94-068, 4/8/94, pp. 25-26 and technical servicing of the power station. -

Is There Life After the Crisis?

is There Life afTer The crisis? Analysis Of The Baltic Media’s Finances And Audiences (2008-2014) Rudīte Spakovska, Sanita Jemberga, Aija Krūtaine, Inga Spriņģe is There Life afTer The crisis? Analysis Of The Baltic Media’s Finances And Audiences (2008-2014) Rudīte Spakovska, Sanita Jemberga, Aija Krūtaine, Inga Spriņģe Sources of information: Lursoft – database on companies Lithuanian Company Register ORBIS – database of companies, ownership and financial data worldwide. Data harvesters: Rudīte Spakovska, Aija Krūtaine, Mikk Salu, Mantas Dubauskas Authors: Rudīte Spakovska, Sanita Jemberga, Aija Krūtaine, Inga Spriņģe Special thanks to Anders Alexanderson, Uldis Brūns, Ārons Eglītis For re-publishing written permission shall be obtained prior to publishing. © The Centre for Media Studies at SSE Riga © The Baltic Center for Investigative Journalism Re:Baltica Riga, 2014 Is There Life After The Crisis? Analysis Of The Baltic Media’s Finances And Audiences (2008-2014) Contents How Baltic Media Experts View the Sector ...............................................................................................................4 Introduction: Media After Crisis ..................................................................................................................................7 Main Conclusions ............................................................................................................................................................8 Changes In Turnover of Leading Baltic Media, 2013 vs 2008 ................................................................................9 -

DICE Best Practice Guide.Pdf

BEST PRACTICE GUIDE Interactive Service, Frequency Social Business Migration, Policy & Platforms Acceptance Models Implementation Regulation & Business Opportunities BEST PRACTICE GUIDE FOREWORD As Lead Partner of DICE I am happy to present this We all want to reap the economic benefi ts of dig- best practice guide. Its contents are based on the ital convergence. The development and successful outputs of fi ve workgroups and countless discus- implementation of new services need extended sions in the course of the project and in conferences markets, however; markets which often have to be and workshops with the broad participation of in- larger than those of the individual member states. dustry representatives, broadcasters and political The sooner Europe moves towards digital switcho- institutions. ver the sooner the advantages of released spectrum can be realised. The DICE Project – Digital Innovation through Co- operation in Europe – is an interregional network We have to recognise that a pan-European telecom funded by the European Commission. INTERREG as and media industry is emerging. The search for an EU community initiative helps Europe’s regions economies of scale is driving the industry into busi- form partnerships to work together on common nesses outside their home country and to strategies projects. By sharing knowledge and experience, beyond their national market. these partnerships enable the regions involved to develop new solutions to economic, social and envi- It is therefore a pure necessity that regional political ronmental challenges. institutions look across the border and aim to learn from each other and develop a common under- DICE focuses on facilitating the exchange of experi- standing. -

Latvia by Juris Dreifelds

Latvia by Juris Dreifelds Capital: Riga Population: 2.1 million GNI/capita, PPP: US$19,090 Source: The data above are drawn from the World Bank’sWorld Development Indicators 2013. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Electoral Process 1.75 1.75 1.75 2.00 2.00 2.00 2.00 1.75 1.75 1.75 Civil Society 2.00 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 Independent Media 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.50 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 Governance* 2.25 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic Governance n/a 2.25 2.00 2.00 2.00 2.50 2.50 2.25 2.25 2.25 Local Democratic Governance n/a 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.25 2.25 2.25 2.25 2.25 2.25 Judicial Framework and Independence 2.00 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 Corruption 3.50 3.50 3.25 3.00 3.00 3.25 3.25 3.50 3.25 3.00 Democracy Score 2.17 2.14 2.07 2.07 2.07 2.18 2.18 2.14 2.11 2.07 * Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects. -

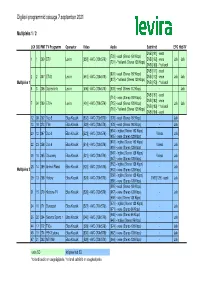

Levira DTT Programmid 09.08.21.Xlsx

Digilevi programmid seisuga 7.september 2021 Multipleks 1 / 2 LCN SID PMT TV Programm Operaator Video Audio Subtiitrid EPG HbbTV DVB [161] - eesti [730] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) 1 1 290 ETV Levira [550] - AVC (720x576i) DVB [162] - vene Jah Jah [731] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) DVB [163] - *hollandi DVB [171] - eesti [806] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) 2 2 307 ETV2 Levira [561] - AVC (720x576i) DVB [172] - vene Jah Jah [807] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) Multipleks 1 DVB [173] - *hollandi 6 3 206 Digilevi info Levira [506] - AVC (720x576i) [603] - eesti (Stereo 112 Kbps) - - Jah DVB [181] - eesti [714] - vene (Stereo 192 Kbps) DVB [182] - vene 7 34 209 ETV+ Levira [401] - AVC (720x576i) [715] - eesti (Stereo 128 Kbps) Jah Jah DVB [183] -* hollandi [716] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) DVB [184] - eesti 12 38 202 Duo 5 Elisa Klassik [502] - AVC (720x576i) [605] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) - Jah 13 18 273 TV6 Elisa Klassik [529] - AVC (720x576i) [678] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) - Jah [654] - inglise (Stereo 192 Kbps) 20 12 267 Duo 3 Elisa Klassik [523] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [655] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [618] - inglise (Stereo 192 Kbps) 22 23 258 Duo 6 Elisa Klassik [514] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [619] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [646] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) 26 10 265 Discovery Elisa Klassik [521] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [647] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [662] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) 28 14 269 Animal Planet Elisa Klassik [525] - AVC (720x576i) - Jah Multipleks 2 [663] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [658] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) -

Relations of the Catholic Church and the Government of the Republic of Lithuania Relations During the Crisis of Covid-19: Partnership Or Dispute?

KAUNAS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, ARTS AND HUMANITIES RESEARCH GROUP - CIVIL SOCIETY AND SUSTAINABILITY Audris Narbutas Relations of the Catholic Church and the Government of the Republic of Lithuania relations during the Crisis of Covid-19: partnership or dispute? Kaunas, 2021 Audris Narbutas received a Bachelor and Master degrees from Vilnius University (Institute of International Relations and Political Science) He is a student of PhD Programme in Political Sciences, which is carried out at Kaunas University of Technology. Among his scientific interests are comparative politics, religious liberty, natural law and electoral behavior. Introduction The religious liberty is one of the most profound and fundamental deep freedoms in the West World. The vast majority of the modern democracies recognize the people’s right to worship God according to the particular traditions and norms of the different religious communities. The state of Lithuania belongs to this family of democracies where the religious liberty plays a significant role in the legal system of the Lithuania. The rights to express and practice each one’s faith are established in the Article 26 of the Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania1 and in the bilateral treaties with the Holy See. Moreover, Lithuania approved the Law on Religious Communities and Associations, which purpose is to establish the legal relations between the different religious communities and associations and the State of Lithuania, Besides, It is an attempt to implement the human -

State of Populism in Europe

2018 State of Populism in Europe The past few years have seen a surge in the public support of populist, Eurosceptical and radical parties throughout almost the entire European Union. In several countries, their popularity matches or even exceeds the level of public support of the centre-left. Even though the centre-left parties, think tanks and researchers are aware of this challenge, there is still more OF POPULISM IN EUROPE – 2018 STATE that could be done in this fi eld. There is occasional research on individual populist parties in some countries, but there is no regular overview – updated every year – how the popularity of populist parties changes in the EU Member States, where new parties appear and old ones disappear. That is the reason why FEPS and Policy Solutions have launched this series of yearbooks, entitled “State of Populism in Europe”. *** FEPS is the fi rst progressive political foundation established at the European level. Created in 2007 and co-fi nanced by the European Parliament, it aims at establishing an intellectual crossroad between social democracy and the European project. Policy Solutions is a progressive political research institute based in Budapest. Among the pre-eminent areas of its research are the investigation of how the quality of democracy evolves, the analysis of factors driving populism, and election research. Contributors : Tamás BOROS, Maria FREITAS, Gergely LAKI, Ernst STETTER STATE OF POPULISM Tamás BOROS IN EUROPE Maria FREITAS • This book is edited by FEPS with the fi nancial support of the European -

2020 Annual Report

Radio and Television Commission of Lithuania RADIO AND TELEVISION COMMISSION OF LITHUANIA 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 17 March 2021 No ND-1 Vilnius 1 CONTENTS CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE ................................................................................................................ 3 MISSION AND OBJECTIVES .......................................................................................................... 5 MEMBERSHIP AND ADMINISTRATION ...................................................................................... 5 LICENSING OF BROADCASTING ACTIVITIES AND RE-BROADCAST CONTENT AND REGULATION OF UNLICENSED ACTIVITIES ............................................................................ 6 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS AND ENFORCEMENT .............................................................. 30 ECONOMIC OPERATOR OVERSIGHT AND CONTENT MONITORING ................................ 33 COPYRIGHT PROTECTION ON THE INTERNET ...................................................................... 41 STAFF PARTICIPATION IN TRAINING AND INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION EFFORTS ........................................................................................................................................................... 42 COMPETITION OF THE BEST IN RADIO AND TELEVISION PRAGIEDRULIAI ................... 43 PUBLICITY WORK BY THE RTCL .............................................................................................. 46 PRIORITIES FOR 2021 ................................................................................................................... -

Vancouver 2010 Olympic Winter Games Rights Holding Broadcasters

Vancouver 2010 Olympic Winter Games Rights Holding Broadcasters Territories Rights Rights Holder Broadcaster Channel / URL Europe Albania TV - FTA EBU RTVSH RTV TV - Cable/Sat Eurosport Eurosport Online http://eurosport.yahoo.com Eurovision http://www.eurovisionsports.tv/olympics Andorra TV - FTA EBU France Télévisions FR2 FR3 TV - FTA RTVE LA2 TELEDEPORTE TVE 1 Online Eurosport http://eurosport.yahoo.com Eurovision http://www.eurovisionsports.tv/olympics Armenia TV - FTA EBU ARMTV ARMTV TV - Cable/Sat Eurosport Eurosport Online http://eurosport.yahoo.com Eurovision http://www.eurovisionsports.tv/olympics Austria TV - FTA EBU ORF ORF1 TV - Cable/Sat Eurosport Eurosport Online http://de.eurosport.yahoo.com Eurovision http://www.eurovisionsports.tv/olympics ORF http://sport.orf.at Belarus TV - FTA EBU TVR BTRC LAD TV - Cable/Sat Eurosport Eurosport Online TVR http://olimpicgames.tvr.by Eurosport http://eurosport.yahoo.com Eurovision http://www.eurovisionsports.tv/olympics Belgium TV - FTA EBU VRT CANVAS EEN TV - Cable/Sat Eurosport Eurosport Online http://eurosport.yahoo.com Eurovision http://www.eurovisionsports.tv/olympics RTBF http://www.rtbf.be/sport VRT http://www.sporza.be/vancouver2010 Bosnia and Herzegovina TV - FTA EBU BHRT BHT1 TV - Cable/Sat Eurosport Eurosport Vancouver 2010 Olympic Winter Games Rights Holding Broadcasters Territories Rights Rights Holder Broadcaster Channel / URL Bosnia and Herzegovina Online Eurosport http://eurosport.yahoo.com Eurovision http://www.eurovisionsports.tv/olympics Bulgaria TV - FTA EBU BNT BNT -

Multiple Documents

Alex Morgan et al v. United States Soccer Federation, Inc., Docket No. 2_19-cv-01717 (C.D. Cal. Mar 08, 2019), Court Docket Multiple Documents Part Description 1 3 pages 2 Memorandum Defendant's Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of i 3 Exhibit Defendant's Statement of Uncontroverted Facts and Conclusions of La 4 Declaration Gulati Declaration 5 Exhibit 1 to Gulati Declaration - Britanica World Cup 6 Exhibit 2 - to Gulati Declaration - 2010 MWC Television Audience Report 7 Exhibit 3 to Gulati Declaration - 2014 MWC Television Audience Report Alex Morgan et al v. United States Soccer Federation, Inc., Docket No. 2_19-cv-01717 (C.D. Cal. Mar 08, 2019), Court Docket 8 Exhibit 4 to Gulati Declaration - 2018 MWC Television Audience Report 9 Exhibit 5 to Gulati Declaration - 2011 WWC TElevision Audience Report 10 Exhibit 6 to Gulati Declaration - 2015 WWC Television Audience Report 11 Exhibit 7 to Gulati Declaration - 2019 WWC Television Audience Report 12 Exhibit 8 to Gulati Declaration - 2010 Prize Money Memorandum 13 Exhibit 9 to Gulati Declaration - 2011 Prize Money Memorandum 14 Exhibit 10 to Gulati Declaration - 2014 Prize Money Memorandum 15 Exhibit 11 to Gulati Declaration - 2015 Prize Money Memorandum 16 Exhibit 12 to Gulati Declaration - 2019 Prize Money Memorandum 17 Exhibit 13 to Gulati Declaration - 3-19-13 MOU 18 Exhibit 14 to Gulati Declaration - 11-1-12 WNTPA Proposal 19 Exhibit 15 to Gulati Declaration - 12-4-12 Gleason Email Financial Proposal 20 Exhibit 15a to Gulati Declaration - 12-3-12 USSF Proposed financial Terms 21 Exhibit 16 to Gulati Declaration - Gleason 2005-2011 Revenue 22 Declaration Tom King Declaration 23 Exhibit 1 to King Declaration - Men's CBA 24 Exhibit 2 to King Declaration - Stolzenbach to Levinstein Email 25 Exhibit 3 to King Declaration - 2005 WNT CBA Alex Morgan et al v. -

Digital Switchover in Central and Eastern Europe

DIGITAL SWITCHOVER IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE: PREMATURE OR KAROL BADLY NEEDED? JAKUBOWICZ 38 - Abstract Preparation for the digital switchover in Central and Karol Jakubowicz was Eastern Europe adds to the complexity of post-Communist (2005-2006) Chairman of the transformation in broadcasting. The following problems are Steering Committee on the apparent: (1) lack of suffi cient understanding of the issues Mass Media and New Com- involved in the digital switch-over, especially as regards the munication Services, Council broadcasting, programming and market issues involved; of Europe; (2) turf wars between broadcasting and telecommuni- e-mail: [email protected]. cations regulatory authorities; (3) the impact of politics on the process of preparation and execution of digital switchover strategies; and (4) in some cases, launching the process prematurely, for inappropriate reasons. Depending Vol.14 (2007), No. 1, pp. 21 1, pp. (2007), No. Vol.14 on one’s point of view, this is either a “premature” digital switchover in countries not yet ready for it, or a case of countries needing a wake-up call to face technological and market realities that they are not responding properly to. Poland is in the process of changing its switchover strat- egy. The process is to start in 2010 with the roll-out of one digital multiplex, covering the whole country, and carrying the existing analogue terrestrial television channels. Plans for further moves are hazy. Meanwhile, many market play- ers are launching alternative projects to take advantage of digital technology, e.g. by means of satellite technology. 21 Preparing for the Digital Switchover in the Context of Post-Communist Transformation In the media fi eld, as elsewhere, post-Communist transformation has meant that Central and Eastern European countries are faced with a major policy over- load. -

Vartotojų Informavimo Planas 2021 M

VARTOTOJŲ INFORMAVIMO APIE ELEKTROS ENERGIJOS RINKOS LIBERALIZAVIMĄ IR JO PROCESĄ PLANAS 2021 m. NUMATOMI KONKURENCINGOS ELEKTROS ENERGIJOS RINKOS SUKŪRIMO ETAPAI 2020-2023 m. Apie 793 tūkst.* II ETAPAS vartotojų ESO pateikia antro etapo Iki šios datos buitinių klientų elektros tiekėją duomenis (kurie pasirenka namų Visuomenės neišreiškė ūkiai, suvartojantys informavimo nesutikimo) >1000 kWh/metus kampanija elektros tiekėjams III ETAPAS 2021.04.05 2021.09.01 2022.12.10 2020.05-12 2021.07 2021.12.10 2023.01.01 II ETAPAS III ETAPAS Iki šios datos Visuomeninis tiekėjas Iki šios datos Įvykdytas 1-asis elektros tiekėją informuoja į pirmąjį elektros tiekėją liberalizavimo pasirenka namų etapą pateksiančius pasirenka visi etapas. ūkiai, suvartojantys buitinius klientus (747 likę namų ūkiai PASIRINKO 97% 1000>5000 tūkst.) apie elektros kWh/metus energijos tiekimo Apie 747 tūkst.* visuomenine kaina vartotojų nutraukimą. PALANKUMO VERTINIMAS Kodėl galimybę pasirinkti elektros energijos tiekėją iš keleto tiekėjų vertinate palankiai? Šaltinis: Visuomenės nuomonės tyrimas dėl elektros energijos rinkos liberalizavimo, 2020 12, UAB „Norstat“ Tyrimo duomenimis apie 98 proc. Lietuvos gyventojų girdėjo apie tai, kad gali rinktis elektros tiekėją savo namams; Tyrimo duomenimis 74 proc. apklaustųjų žino arba girdėjo apie informacinę svetainę Pasirinkitetiekeja.lt; 53% teigia trūkstantys daugiau informacijos apie tiekėjo pasirinkimo procesą. KOMUNIKACIJOS KELIAS ŽINOMUMAS SUSIDOMĖJIMAS VEIKSMAS AIŠKIOS NAUDOS: LAISVĖ RINKTIS, AIŠKUMAS: INFORMAVIMAS / EDUKAVIMAS naudų ir patarimų komunikavimas. asmens duomenų sauga, Visuomenėje suformuoti vykstančio Gerosios patirtys. Daugiau pasirinkimo proceso pokyčio žinomumą. Informuoti klientus ir akcentų: kas, kada ir kaip keisis. komunikavimas, skatinimas suteikti kuo daugiau informacijos apie nelikti garantiniame tiekime. pokytį, jo tikslus, naudą, eigą. Aiški ir paprasta, asmeniškai į žmogų nukreipta komunikacija.