Rom Und Die Provinzen 387 Holger Schaaff, Antike Tuffbergwerke Am

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tufsteen Uit De Eifel TIMO G

Römer (midden in de driekhoek tussen de boogsegmenten), Ettringer (linker boogsegment) en Weiberner tuf (rechter boogsegment aan de Sint Amelbega in Susteren). Tufsteen uit de Eifel TIMO G. NIJLAND In verschillende perioden zijn diverse tufstenen uit de Eifel in Nederland TNO ingevoerd om te dienen als bouwmateriaal: de zogenaamde Römer tuf, in POSTBUS 49 de Romeinse tijd en in de periode van Romaanse architectuur in de 2600 AA DELFT Middeleeuwen, Weiberner tuf, in de late Middeleeuwen en opnieuw vanaf [email protected] halverwege de 19e eeuw en Ettringer tuf, eveneens vanaf halverwege de 19e eeuw. Tezamen vormen ze een niet onaanzienlijk deel van de bouw- massa in Nederlandse monumenten: Een succesverhaal voor een steen die erg poreus en niet al te sterk is. Eifel vulkanisme uitgebreid beschreven in talloze boe- De Eifel maakt net als het Zevenge- ken en artikelen (b.v. Frenchen, 1971, bergte deel uit van een min of meer Schmincke, 1988, 2000, 2009), zodat oost-west lopende gordel van vulkaan- hier volstaan wordt met een kort gebieden in Duitsland. Het vulkanis- overzicht. me begint in het Tertiair en is nu sluimerend, met als laatste grote uit- Het Eifel vulkanisme leverde een barsting die van de Laacher See vul- reeks gesteenten op die voor de bouw kaan 11.900 v. Chr. Het vulkanisme is en aanverwante sectoren van belang S TICHTING G EOLOGISCHE A KTIVITEITEN 90 7 B OUWEN MET N ATUURSTEEN - 2015 zijn (geweest): Poreuze basaltlava’s uit de Oost-Eifel die sinds de Steentijd de grondstof waren voor een uitgebreide maal- en molensteenindustrie. Deze basalten (Mayen, Mendig) werden lokaal ook als bouwsteen gebruikt en zijn na de Tweede Wereldoorlog in Nederland toegepast ter vervanging van zandsteen (een gevolg van het Zandsteenbesluit). -

The Volcanic Foundation of Dutch Architecture: Use of Rhenish Tuff and Trass in the Netherlands in the Past Two Millennia

The volcanic foundation of Dutch architecture: Use of Rhenish tuff and trass in the Netherlands in the past two millennia Timo G. Nijland 1, Rob P.J. van Hees 1,2 1 TNO, PO Box 49, 2600 AA Delft, the Netherlands 2 Faculty of Architecture, Delft University of Technology, Delft, the Netherlands Occasionally, a profound but distant connection between volcano and culture exists. This is the case between the volcanic Eifel region in Germany and historic construction in the Netherlands, with the river Rhine as physical and enabling connection. Volcanic tuff from the Eifel comprises a significant amount of the building mass in Dutch built heritage. Tuffs from the Laacher See volcano have been imported and used during Roman occupation (hence called Römer tuff). It was the dominant dimension stone when construction in stone revived from the 10th century onwards, becoming the visual mark of Romanesque architecture in the Netherlands. Römer tuff gradually disappeared from the market from the 12th century onwards. Early 15th century, Weiberner tuff from the Riedener caldera, was introduced for fine sculptures and cladding; it disappears from use in about a century. Late 19th century, this tuff is reintroduced, both for restoration and for new buildings. In this period, Ettringer tuff, also from the Riedener caldera, is introduced for the first time. Ground Römer tuff (Rhenish trass) was used as a pozzolanic addition to lime mortars, enabling the hydraulic engineering works in masonry that facilitated life and economics in the Dutch delta for centuries. Key words: Tuff, trass, Eifel, the Netherlands, natural stone 1 Introduction Volcanic tuffs have been used as building stone in many countries over the world. -

1 89/1/16 War Services Committee World War I Record of Services

1 89/1/16 War Services Committee World War I Record of Services Card Files, 1918-1920 Technical Training Schools Bellevue College, Omaha, Nebraska U.S. Training Detachment of Beloit College, Beloit, Wisconsin Birmingham Southern College, Birmingham, Alabama Bliss Electrical School, U.S. Army Technical Training Detachment, Takoma Park, D.C. U.S. School of Mechanics at Benson Polytechnical School, Portland, Oregon U.S. School of Mechanics at Benson High School, Portland, Oregon Brooklyn College (St. John’s College), Brooklyn, New York Buell Camp, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky California State Normal School, Los Angeles, California California University, School of Aeronautics, Berkeley, California Polish National Alliance College, Cambridge Springs, Pennsylvania Carnegie Institute of Technology, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Carleton College, Northfield, Minnesota Central Academy and College, McPherson, Kansas Chicago Public Library, Chicago, Illinois Army Training Section, Old South Division High School, Chicago, Illinois University of Chicago, Army Technical Training School, Chicago, Illinois Cincinnati Public Schools, Cincinnati, Ohio New Y.M.C.A. Building, Cincinnati, Ohio St. Xavier College, Student Army Training Corps, Cincinnati, Ohio University of Cincinnati, Auto-Mechanics Training School, Cincinnati, Ohio Colby College, Waterville, Maine Colgate University, Hamilton, New York Colorado College, Colorado Springs, Colorado Colorado School of Mines, Golden, Colorado Colorado State Agricultural College, Fort Collins, Colorado -

1. Satzung Zur Änderung Der Hauptsatzung Der Verbandsgemeinde Pellenz Vom 21.11.2019

1. Satzung zur Änderung der Hauptsatzung der Verbandsgemeinde Pellenz vom 21.11.2019 Der Verbandsgemeinderat der Verbandsgemeinde Pellenz hat auf Grund der §§ 24 und 25 Gemeindeordnung (GemO), der §§ 7 und 8 der Landesverordnung zur Durchführung der Gemeindeordnung (GemODVO), des § 2 der Landesverordnung über die Aufwandsentschädigung kommunaler Ehrenämter (KomAEVO) und des § 2 der Feuerwehr- Entschädigungsverordnung die folgende Hauptsatzung beschlossen, die hiermit bekannt gemacht wird: Artikel I Die Hauptsatzung der Verbandsgemeinde Pellenz vom 27.06.2019 wird wie folgt geändert: § 2 (Ausschüsse des Verbandsgemeinderates) erhält folgende Fassung: (1) Der Verbandsgemeinderat bildet folgende Ausschüsse a) Haupt- und Personalausschuss b) Rechnungsprüfungsausschuss c) Finanzausschuss d) Bau- und Vergabeausschuss e) Planungs- und Umweltausschuss f) Werksausschuss g) Feuerwehrausschuss h) Ausschuss für Soziales, Familie und Daseinsvorsorge i) Ausschuss für Tourismus, Kultur und Sport j) Schulträgerausschuss (2) Die Ausschüsse nach Absatz 1 Buchstabe a) bis i) bestehen aus zehn Mitgliedern und Stellvertretern. Die Zusammensetzung des Schulträgerausschusses bestimmt sich nach Spezialgesetz. (3) Die Mitglieder und Stellvertreter des Haupt- und Personalausschusses werden aus der Mitte des Verbandsgemeinderates gewählt. Die Mitglieder und Stellvertreter der Ausschüsse nach Abs. 1 Buchst. b) – i) können aus der Mitte des Verbandsgemeinderates und aus sonstigen Bürgern gewählt werden. Die Zahl der Ratsmitglieder beträgt mindestens fünf Mitglieder -

Inklusiver Badminton Mitma Für Jedermann Siver Badminton

Ausschreibung Inklusiver Badminton Mitmach -Tag für jedermann am 29.11 .2015 in Plaidt / Pellenz Ausschreibung Im Rahmen der Initiative „Einf ach gemein sam – Sport in Kruft“ laden Special Oly m- pics Rheinland-Pfalz und die Barmherzigen Brüder Saff ig zusammen mit der DJK Plaidt, der IGS Pellenz sowie DJK Kruft/ Kretz und dem TV Kruft Menschen mit und ohne Behinderung zum inklusiven Badminton Mitmach -Tag am 29.11 .2015 nach Plaidt ein. Seit über 20 Jahren sind die Badminton -Turniere der Barmherzigen Brüder Saffig fester Bestandteil des Veranstaltungskalenders in der Region Pellenz . Im Rahmen der Initiative „Einfach gemeinsam“ findet diese Veranstaltung in Kooperation mit Special Olympics Rheinland-Pfalz erstmals als inklusives Jedermann-Angebot statt und richtet sich gleichermaßen an Menschen mit und ohne Handicap. Bestandteile bilden der inklusive Doppel -Wettbewerb sowie der Erwerb des Ba d- minton Spiel- und Sportabzeichens. Hierbei steht weniger die sportliche Höchstlei s- tung als vielmehr das gemeinsame Miteinander von Menschen mit und ohne Hand i- cap im Fokus. Ein Doppel besteht aus jeweils einem Partner mit und ohne Handicap. Hobbysportler ohne Badminton-Erfahrung sind ebenso herzlich willkommen wie Fortgeschrittene jeden Alters. Eine Teilnahme als Team ist ebenfalls möglich. Bei der Teilnahme als Einzelsportler werden die inklusiven Doppel vor Ort gebildet. Der Erwerb des Sport- & Spielabzeichens ist auch ohne eine Teilnahme am Wettbe werb kurzfristig möglich. Neben dem Sport- & Mitmach-Angebot erwarten die Teilnehmer ein gemeinsames Mittagessen und feierliches Rahmenpro gramm. Top Partner Die Veranstaltung ist Bestandteil der Initiative „Einfach gemeinsam – Sport in Kruft“. Ziel der Kooperationspartner ist es, den Sport in der Region Pellenz nachhaltig inkl u- Förderer siver zu gestalten. -

07.01.2021 14:19:43 Kursindex Kursart Fahrzeug Fahrtnummer Ve

VRM Linie : 319 R(71) - Betreiber: VRM - Seite 1 Ausdruck vom : 07.01.2021 14:19:43 Kursindex K 1 K 2 K 3w0 K 4w0 K 5w0 K 6w0 K 7w0 K 8w0 K 9w0 K 10 K 11 K 12 Kursart KA 13 KA 1 KA 8 KA 2 KA 3 KA 7 KA 9 KA 10 KA 6 KA 5 KA 11 KA 12 Fahrzeug Bn2 Bn2 Bn2 Bn2 Bn2 Bn2 Bn2 Bn2 Bn2 Bn2 Bn2 Bn2 Fahrtnummer Verkehrstage A A A A A A A A A 1234 1234 1234 Einschränkung S S S S S S S S S SSSS SSSS SSSS Produkt Infozeile 1 Infozeile 2 Kommentar Ochtendung Waldorferhof, Nochtendung 06:47 Ochtendung Auf Münsterhöh, Vkobern-gondorf 06:48 Ochtendung Schillerstraße, Vmayen 06:54 Ochtendung Raiffeisenplatz, Vmayen 06:55 Ochtendung Plaidter Straße, Nkruft_Bussteig C 06:56 Ochtendung Kartalsweg, Vplaiderstr 06:58 Ochtendung Kulturhalle, Vplaidterstr 06:59 Saffig Dorfplatz, Vochtendung_Bussteig C 07:04 Saffig Von der Leyenstraße, Nplaidt 07:05 Plaidt Rauschermühle/Vulkanpark, Vsaffig 07:06 Plaidt IGS, Vmiesenheimerstr | 13:35 13:35 16:10 Plaidt Miesenheimer Straße/IGS, Ndorfplatz | 12:34 13:20 13:25 | | | 16:10 Plaidt Am Kürchen, Vmiesenheim | 12:35 13:21 13:26 | | | 16:11 Plaidt Hummerichstraße, Vsaffigerstr 07:07 | | | | | | | Plaidt Nettebrücke, Ndorfplatz 07:09 | | | | | | | Plaidt Dorfplatz, Nxxx 07:12 | | | | | | | Plaidt Bahnhofstraße, Vdorfplatz 07:13 12:37 13:23 13:28 | | | 16:13 Plaidt Pommerhof, Nkruft 07:15 12:39 13:25 13:30 | | | 16:15 Kretz Zentralhaltestelle, Nkruft 07:17 12:41 | 13:32 | | 16:17 | Kretz Kirche, Nbundesstr | 07:39 | | | | | | | Kretz Römerbergwerk, Nkruft 07:18 07:40 12:42 | 13:33 | | 16:18 | Kruft Grundschule, Nbahnhofstr | 07:45 -

OFB Ochtendung Ergänzungen

Familienbuch Ochtendung mit den zugehörigen Wohnplätzen Waldorfer Höfe – Sackenheimer Höfe – Emminger Höfe – Fressenhöfe –Alsinger Höfe 16. - 20. Jahrhundert Ergänzungen CARDAMINA Verlag Susanne Breuel Herbst im Park am Seehotel in Maria Laach Realisation: CARDAMINA® Verlag Susanne Breuel, 56637 Plaidt Tel: / Fax 0700 2827 3835 Internet: www.cardamina.de / E-Mail: [email protected] Ergänzungen zum Ortsfamilienbuch Ochtendung (welches in der CSB Reihe erschienen ist: CSB-00147) Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk ist in allen Teilen urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jegliche Verwertung – Vervielfältigung, Mikroverfilmung, Übersetzung, Bearbeitung, Speicherung und Verarbeitung in elektroni- schen Systemen – bedarf der vorherigen schriftlichen Zustimmung der Autoren. - Ergänzungen OFB Ochtendung - Liebe Familienforscher, in der Anlage finden Sie die Ergänzungen / Berichtigungen zum Familienbuch Ochtendung, die nach der Fertig- stellung mitgeteilt oder eingegangen sind. Bei Angaben durch von Familienangehörigen, Nachkommen oder Be- wohnern kann es zu Verwechslungen kommen, wenn z.B. gleiche Namen im Raume standen, was sich dann bei der Zuordnung des Partners bemerkbar machte. Oftmals waren die Eltern nur mit dem „Spitznamen“ bekannt. Bei einem solchen Werk können Fehler auftauchen und die Familie Severin bitten Sie daher um Nachsicht. Sie können die Ergänzungen lose in das Familienbuch einlegen oder Sie ergänzen die Daten mit einem Bleistift bei der jewei- ligen Familie. Um Verwechslungen bei Familiennamen, die auch als Vornamen auftreten, zu vermeiden, wurden diese in Großbuchstaben geschrieben. Sie ist durch zwei Linien eingegrenzt. Weitere Ergänzungen, vor allem bei den Daten zwischen 1798 – 1824, können Sie auf der Homepage von Manfred Rüttgers erfahren:.. http://www.familienforschung-maifeld.de/html/ofb_ochtendung.html Erläuterung: FB Nr. = Nummer der Familie im Familienbuch // S. = Seite im Familienbuch // DS = Datenschutz Mit Vermerkleiste ist jener Abschnitt gemeint, der nach dem Elternteil, aber vor den Eintragungen der Kinder ist. -

Wohnmarktbericht.Pdf

Editorial Inhalt Service 8 Kauf 16 Versicherung Was Interessenten beachten sollten, Optimaler Schutz für Haus und Eigentümer wenn sie sich eine Immobilie zulegen 18 Verkauf 13 Finanzierung So finden Immobilienbesitzer den Wie Käufer und Bauherren die Belastung fairen Preis für ihr Objekt möglichst gering halten Die beiden Vorstände Karl-Josef Esch und Christoph Weitzel stehen für die Erfüllung der persönlichen Wohnträume ihrer Kunden. Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, wer eine Immobilie kaufen, verkaufen oder vermieten möchte, zielle Belastung niedriger ist. Im Vordergrund steht die sorgfältige sollte vor allem gut darüber Bescheid wissen, wie sich der Wohn- Auswahl des Objekts und eine kluge Finanzierung. Wir unterstützen markt vor Ort entwickelt bzw. in der letzten Zeit entwickelt hat. Sie bei Ihrem Vorhaben mit unserem Wohnmarktbericht. Deshalb geben die Kreissparkasse Mayen und das iib Dr. Hetten- bach Institut, Deutschlands Nummer eins in der Immobilien-Markt- Für alle weiteren Fragen steht Ihnen unser Expertenteam des forschung, erstmalig gemeinsam den Wohnmarktbericht für die ImmobilienCenters zur Verfügung. Egal ob Kauf oder Verkauf, Haus Region heraus. oder Wohnung, Neu- oder Altbau, Finanzierung und Absicherung, wir stehen Ihnen zur Seite! Wir sind die Spezialisten rund um das In diesem Bericht informieren wir über die allgemeine Situation Thema Vermittlung, Finanzierung und Versicherungen. des lokalen Immobilienmarktes. Er wurde vom iib Dr. Hettenbach Institut unabhängig erstellt und liefert auf transparente und einfach Wir wünschen Ihnen viel Vergnügen beim Lesen! nachzuvollziehende Art und Weise Richtpreise für Immobilien. Denn nur wenn alle auf den gleichen Richtpreis vertrauen können, Ihre Kreissparkasse Mayen wird der Immobilienmarkt sicherer, professioneller und besser. Dadurch können auch Verkauf oder Vermietung einfacher erfolgen. -

DJK „Wernerseck“ 1927 E.V. Plaidt Samstag, 11. März 2017

DJK „Wernerseck“ 1927 e.V. Plaidt Ausgabe 5 - Saison 2016/2017 11. März 2017 Herzlich Willkommen zu den Heimspielen der DJK „Wernerseck“ Plaidt Fußballteams. Folgende Begegnungen stehen an diesem Wochenende auf dem Spielplan: Samstag, 11. März 2017 15.30 Uhr: DJK Plaidt II vs. DJK Kruft/Kretz II 17.30 Uhr: DJK Plaidt I vs. SG Boos/Weiler/Nachtsheim I Kreisliga B Mayen: DJK Wernerseck Plaidt vs. SG Boos/Weiler/Nachtsheim Grußwort von Adler-Coach Andreas Samson Zunächst möchte ich unsere heutigen Gäste der SG Boos/Weiler/Nachtsheim und alle Anhänger am Plaidter Pommerhof begrüßen. Dies ist unser erstes Pflichtspiel auf heimischem Geläuf im neuen Jahr 2017. Mit der SG erwarten wir eine Mannschaft, die aktuell mit 16 Punkten zwar nur auf Platz 11 der Tabelle rangiert, jedoch immer noch 10 Punkte Vorsprung auf die Abstiegsränge hat. Zudem steht mit Markus Laux ein Trainer an der Linie, der unsere Mannschaft bestens kennt und genau weiß, wo er den Hebel anzusetzen hat. Darauf müssen wir uns einstellen. Ein Blick auf den Leistungsstand meiner Mannschaft, stellt mich sehr zufrieden. Die Wintervorbereitung lief besser als bei vielen anderen Mannschaften, zumindest wenn man die Stimmen meiner Trainerkollegen aus der Presse so hört. Wir konnten alle Testspiele durchführen, wenn auch mit wechselhaften Ergebnissen, was diverse Gründe hatte auf die ich hier aber nicht weiter eingehen möchte. Fakt ist: Wenn es zählt sind wir da! Das haben wir am vergangenen Wochenende in Langenfeld, durch den späten 0:1-Auswärtssieg, eindrucksvoll bewiesen. Laufbereitschaft, Wille, Mut und Leidenschaft waren bei meinen Spielern durch die Bank vorhanden. Das macht mich als Trainer natürlich sehr stolz! Der dreifache Punktgewinn bescherte uns 25 Zähler auf der Habenseite, so dass wir die restliche Saison in Ruhe angehen können. -

Landschaftsplanverzeichnis Rheinland-Pfalz

Landschaftsplanverzeichnis Rheinland-Pfalz Dieses Verzeichnis enthält die dem Bundesamt für Naturschutz gemeldeten Datensätze mit Stand 15.11.2010. Für Richtigkeit und Vollständigkeit der gemeldeten Daten übernimmt das BfN keine Gewähr. Titel Landkreise Gemeinden [+Ortsteile] Fläche Einwohner Maßstäbe Auftraggeber Planungsstellen Planstand weitere qkm Informationen LP Adenau Ahrweiler Adenau 257 13.000 10.000 VG Adenau Brandenfels 1974; 1974 Od 130 LP Adenau (1.FS) Ahrweiler Adenau 257 13.000 5.000 VG Adenau, Uni. Inst. f. Städtebau, Uni 1988; 1989 10.000 Bonn Bonn / Oyen LP Adenau (2.FS) Ahrweiler Adenau 258 15.423 10.000 VG Adenau Nick, C+S Consult 1996 LP Altenahr Ahrweiler Ahrbrück, Altenahr, Berg, Dernau, 153 11.200 10.000 VG Ahrweiler Brandenfels u. Pahl 1984 Heckenbach, Hönningen, Kalenborn, Kesseling, Kirchsahr, Lind, Mayschoß, Rech LP Altenahr (FS) Ahrweiler Ahrbrück, Altenahr, Berg, Dernau, 154 12.000 5.000 VG Altenahr Bauabteilung i.B. Heckenbach, Hönningen, 10.000 Kalenborn, Kesseling, Kirchsahr, Lind, Mayschoß, Rech LP Bad Breisig Ahrweiler Bad Breisig, Brohl-Lützing, 50 10.100 5.000 VG Bad Breisig LSRP 1984 Gönnersdorf, Waldorf 10.000 LP Bad Breisig (FS) Ahrweiler Bad Breisig, Brohl-Lützing, 42 13.027 5.000 VG Bad Breisig Sprengnetter u. i.B. Gönnersdorf, Waldorf 10.000 Partner LP Bad Ahrweiler Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler 64 28.300 10.000 ST Bad Neuenahr Penker 1976; 1976 Neuenahr-Ahrweiler 50.000 LP Bad Ahrweiler Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler 63 27.456 10.000 ST Bad Neuenahr Terporten i.B. Neuenahr-Ahrweiler (FS) LP Brohltal Ahrweiler -

Vulkanismus Und Archäologie Des Eiszeitalters Am Mittelrhein

Baales2_01(Text)_D 20.11.2003 11:42 Uhr Seite 43 MICHAEL BAALES* VULKANISMUS UND ARCHÄOLOGIE DES EISZEITALTERS AM MITTELRHEIN DIE FORSCHUNGSERGEBNISSE DER LETZTEN DREISSIG JAHRE Kaum eine Region in Deutschland bzw. Mitteleuropa ist so reich an Aufschlüssen mit unterschiedlich al- ten Ablagerungen des Eiszeitalters (Pleistozän) wie das Mittelrheingebiet um Koblenz - Neuwied - An- dernach - Mayen (Abb. 1). Verdankt wird dies u.a. dem Vulkanismus der Osteifel, dessen wichtigste Hin- terlassenschaften – zahlreiche Schlackenkegel und mächtige Bimsdecken – seit vielen Jahrzehnten intensiv abgebaut werden. Vor allem diese industrielle Steingewinnung legte immer wieder Hinterlassenschaften des eiszeitlichen Menschen und seiner Umwelt frei, die besonders seit den 1960er Jahren untersucht wur- den. Die Eiszeitarchäologie im Mittelrheingebiet begann jedoch schon 80 Jahre früher, als Constantin Koe- nen am 10.2.1883 auf dem Martinsberg bei Andernach im Lehm unter dem späteiszeitlichen Bims des Laacher See-Vulkans Tierknochen und Steingeräte bemerkte. Er benachrichtige Hermann Schaaffhausen aus Bonn, der sogleich mit der Ausgrabung einer späteiszeitlichen Siedlungsstelle begann (H. Schaaff- hausen 1888). Die Grabungsgeschichte war damit für Andernach noch nicht beendet, folgten doch zwei weitere Ausgrabungsperioden in den späten 1970er/frühen 1980er Jahren (S. Veil 1982a; 1982b; 1984; G. Bosinski 1996; H. Floss u. T. Terberger 2002) sowie zwischen 1994 und 1996 (S. Bergmann u. J. Holz- kämper 2002; J. Kegler 2002). Nach den Pioniertaten H. Schaaffhausens dauerte es aber bis zur Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts, bis ein wei- terer (spät)eiszeitlicher Fundplatz entdeckt und auch untersucht wurde. Dieser lag in Urbar bei Koblenz und wurde 1966 erstmals in Ausschnitten freigelegt; die kleinräumigen Geländearbeiten zogen sich bis 1981 hin (M. -

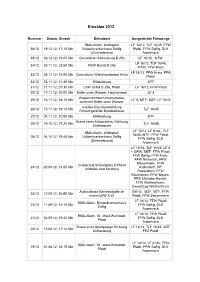

Einsätze 2012

Einsätze 2012 Nummer Datum, Uhrzeit Einsatzart Ausgerückte Fahrzeuge BMA-Alarm, Wohnpark LF 16/12, TLF 16/45, FFW 36/12 19.12.12, 17:10 Uhr Brüderkrankenhaus Saffig Plaidt, FFW Saffig, DLK (Zimmerbrand) Andernach 35/12 02.12.12, 13:05 Uhr Gemeldete Hilfeleistung B 256 LF 16/12, MTW LF 16/12, TLF 16/45, 34/12 30.11.12, 23:50 Uhr PKW Brand B 256 MTW, FFW Kretz LF 16/12, FFW Kretz, FFW 33/12 28.11.12, 14:00 Uhr Gemeldeter Wohnhausbrand Kretz Plaidt 32/12 23.11.12, 11:30 Uhr Hilfeleistung MTF 31/12 21.11.12, 07:30 Uhr LKW Unfall B 256, Plaidt LF 16/12, FFW Plaidt 30/12 17.11.12, 10:00 Uhr Keller unter Wasser, Hochstrasse LF 8 Wasserrohrbruch Hochstrasse, 29/12 16.11.12, 18:10 Uhr LF 8, MTF, MZF, LF 16/12 mehrere Keller unter Wasser unklare Rauchentwicklung 28/12 15.11.12, 19:15 Uhr TLF 16/45 Firmemgelände Bundestrasse 27/12 07.11.12, 10:00 Uhr Hilfeleistung MTF Brand eines Motorrollers, Richtung 26/12 19.10.12, 17:20 Uhr TLF 16/45 Ochtendung LF 16/12, LF 8+AL, TLF BMA-Alarm, Wohnpark 16/45, MTF, FFW Plaidt, 25/12 04.10.12, 19:45 Uhr Brüderkrankenhaus Saffig FFW Saffig, DLK (Zimmerbrand) Andernach LF 16/12, TLF 16/45, LF 8 + SWW, MZF, FFW Plaidt, FFW Saffig, FFW Kretz, FFW Nickenich, FFW Miesenheim, FFW Großbrand Schrottplatz in Plaidt 24/12 20.09.12, 13:05 Uhr Andernach, WF (Altautos und Altreifen) Rasselstein, FFW Kottenheim, FFW Mayen, FFW Mülheim-Kärlich, FFW Weißenthurm, Umweltzug Weißenthurm Auslaufende Betriebsstoffe an GW-G, MZF, MTF, FFW 23/12 12.09.12, 16:55 Uhr einem LKW A 61 Plaidt, FFW Bassenheim LF 16/12, FFW Plaidt, BMA-Alarm, Brüderkrankenhaus 22/12 11.09.12, 14:10 Uhr FFW Saffig, DLK Saffig Andernach LF 16/12, FFW Plaidt, BMA-Alarm, St.