Download the Article Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art Ab S Tr Ait Et C O Nte M P O R

ART ABSTRAIT ET CONTEMPORAIN SAMEDI 23 ET DIMANCHE 24 OCTOBRE 2010 PARIS – HôTEL MARCEL DASSAULT 15H ART ABSTRAIT ET CONTEMPORAIN SAMEDI 23 ET DIMANCHE 24 OCTOBRE 2010 PARIS – HôTEL MARCEL DASSAULT 15H ARTCURIAL BRIEST – POULAIN – F.TAJAN Hôtel Marcel Dassault 7, Rond-Point des Champs-Élysées 75008 Paris ART ABSTRAIT ET CONTEMPORAIN ASSOCIÉS VENTE N°1899 EXPOSITIONS PUBLIQUES : Francis Briest, Co-Président Commissaire-priseur Jeudi 21 octobre 2010 Hervé Poulain Francis Briest 11–19h François Tajan, Co-Président Vendredi 22 octobre 2010 Spécialistes 11–19h Martin Guesnet, DIRECTEURS ASSOCIÉS directeur associé +33 (0)1 42 99 20 31 VENTE LE SAMEDI 23 OCTOBRE Violaine de La Brosse-Ferrand [email protected] À 15H Martin Guesnet ET LE DIMANCHE 24 OCTOBRE Fabien Naudan Hugues Sébilleau, À 15H Arnaud Oliveux Spécialistes Catalogue visible sur internet +33 (0)1 42 99 16 35 / 16 28 www.artcurial.com [email protected] [email protected] Gioia Sardagna Ferrari Spécialiste Italie +33 (0)1 42 99 20 36, [email protected] Harold Wilmotte Spécialiste junior +33 (0)1 42 99 16 24, [email protected] Marc Jallon Consultant Art aborigène australien +33 (0)6 36 26 88 74, Comptabilité vendeurs [email protected] Sandrine Abdelli + 33 (0)1 42 99 20 06 Florence Latieule [email protected] Catalogueur +33 (0)1 42 99 20 38, Comptabilité acheteurs [email protected] Nicole Frerejean + 33 (0)1 42 99 20 45 Renseignements [email protected] Sophie Cariguel, +33 (0)1 42 99 20 04, [email protected] Ordres d’achat, enchères par téléphone Anne-Sophie Masson +33 (0)1 42 99 20 51 [email protected] 2 ART ABSTRAIT ET CONTEMPORAIN — 23 ET 24 OCTOBRE 2010. -

2016/17 Trinity Hall

A year in the life of the Trinity Hall community 2016/17 Trinity Hall Academic Year 2016/17 2016/17 2 Trinity Hall Reports from our Officers Hello and welcome to the Trinity Hall Review 2016/17, looking back on an exciting academic year for the College community. Major milestones this year include a number of events and projects marking 40 years since the admission of women to Trinity Hall, the completion of WYNG Gardens and the acquisition of a new portrait and a new tapestry, both currently on display in the Dining Hall. We hope you enjoy reading the Review and on behalf of everyone at Trinity Hall, thank you for your continued and generous support. Kathryn Greaves Alumni Communications Officer Stay in touch with the College network: 30 TrinityHallCamb Alumni News inside Reports from our Officers 2 The Master 2 The Bursar 4 The Senior Tutor 7 The Graduate Tutor 8 The Admissions Tutor 10 The Dean 11 The Development Director 12 The Junior Bursar 14 The Head of Conference and Catering Services 15 The Librarian 16 The Director of Music 17 College News 18 The JCR President’s Report 20 The MCR President’s Report 21 Student Reports 22 Fellows’ News 24 Seminars and Lectures 26 Fundraising 28 18 Alumni News 30 THA Secretary’s Report 32 College News Alumni News 34 In Memoriam 36 2016/17 Information 38 List of Fellows 40 College Statistics 44 Fellows and Staff 48 List of Donors 50 Get involved 59 Thank you to all who have contributed to this edition of the Trinity Hall Review. -

Freshers' Guide

Freshers’ Guide 2020 Freshers’ Emmanuel Postgraduate Prepared by Emmanuel College MCR Contents Contents 1 Welcome 2 MCR Committee 4 How to get here 10 College 12 Accommodation 13 What to bring 18 What’s What and Who’s Who 22 Welfare 26 Disability 29 Students with Families 32 Healthy relationships 33 International students 42 Religion 45 Being Green 46 Computing 47 Sports and other activities 50 Cambridge Life 53 Freshers’ week 58 1 Welcome to Emmanuel Hello! Congratulations on joining Emmanuel — ‘Emma’ as it is affectionately known — and beginning your new postgraduate course. We are thrilled that you have chosen Emma to be your college and we hope that you are excited to be starting at Emma, and at Cambridge. But you probably also have a lot of questions. We hope that this guide will provide answers to some of those questions along with lots of other useful information, both for planning your arrival and once you are here. But let’s start right at the beginning, because some of you may be wondering what Emmanuel even is - you thought you were joining Cambridge! Well, you are. The University of Cambridge is at the same time one thing and many, being made up of many faculties and departments, and colleges. As a postgraduate student you will belong to both a department, responsible for your education, and to a college, responsible for your pastoral care, accommodation and an important part of your social life. So who are ‘we’? Emma has its own student unions, who represent the students to College and vice versa, and run various events. -

May Week 2008 Is Published by Varsity Publications Ltd

Here is Summer poems drawings stories photographs T-Rex going home ferret wheels Cancun Thomas De Quincey’s London prostitutes David Shrigley ice cream Paul Smith’s fried egg unseen Cambridge Minsk men Sark scrambles tangerines Blogotheque accordions on roofs cellos on punts Scroobius Pip Peggy Sue and the Pirates’ search for whiskey Jens Lekman pilots Grobs Titanic incest fucking in Californian accents Auntie Amy mix tape a minha menina 1 Oh dear. I went to one May Ball. Was it in Trinity (I was in Peterhouse)? I remember: my girlfriend coming from London and staying (illegally) in my digs opposite the Fitzwilliam Museum; not enough drink, not enough dope (we called it pot); undergraduates behaving as if they were adults from an earlier gen- eration; undergraduates puking on the grass at dawn (not me); Georgie Flame and the Blue Flames; twisting; feeling obliged to stay much longer at the ball than we wanted because the tickets had been so exorbitantly expensive; dur- ing May Week feeling that I should be having the time of my life but wasn’t. I entirely wasted my time at Cambridge, I was on the King’s May Ball commit- did badly in my exams (missed one alto- tee for 1968. We had booked some tre- gether), scraped a degree and have felt mendous groups, including the up and vaguely uneasy ever since at the expense coming Tyrannosaurus Rex (they’d had of spirit in a waste of shame... their rst small hit the month before and Richard Eyre didn’t become T-Rex until 1970.) Some idiot on the committee also booked a bouncer who was charged with making sure the acts did their full contract and no funny business. -

Newsletter Is Published by the College

Trinity Hall cover 2013_Trinity Hall cover 07/10/2013 08:51 Page 1 3 1 / 2 1 0 2 R A E Y C I M E D A C A R E T T E L S W E N L L A H Y T I N I R T The Trinity Hall Newsletter is published by the College. Newsletter Thanks are extended to all the contributors. ACADEMIC YEAR 2012/13 The Development and Alumni Office Trinity Hall, Cambridge CB2 1TJ Tel: +44 (0)1223 332562 Fax: +44 (0)1223 765157 Email: [email protected] www.trinhall.cam.ac.uk Return to contents www.trinhall.cam.ac.uk 1 Trinity Hall Newsletter ACADEMIC YEAR 2012/13 College Reports ............................................................................. 3 Trinity Hall Lectures .................................................................. 49 Student Activities, Societies & Sports ....................................... 89 Trinity Hall Association .......................................................... 109 The Gazette ...............................................................................115 Keeping in Touch ...................................................................... 129 Section One College Reports Return to contents www.trinhall.cam.ac.uk 3 From the Master The academic year 2012/13 closed with a sense of achievement and pride. The performance in the examinations was yet again outstanding: we finished third in the table of results, consolidating our position as one of the high achieving colleges in the College Reports University. This gratifying success was not the result of forcing the students into the libraries, laboratories and lecture theatres at the expense of other elements of life in College. Quite the contrary: one of the most pleasurable aspects of life in College at the moment is that students enjoy their academic work and find it a source of endless interest. -

2017/18 Trinity Hall Review 2017/18 Trinity Hall CAMBRIDGE

TRINITY HALL CAMBRIDGE Trinity Hall Review 2017/18 Academic Year 2017/18 Academic Year Trinity Hall Trinity A year in the Hall life community of the Trinity 2017/18 2017/18 2 Trinity Hall Reports from our Officers Welcome to the fifth edition of the Trinity Hall Review. We hope you enjoy reading about the year in College. A highlight for us was the Alumni Summer Party in July. We were delighted to welcome over 190 alumni and guests to a sunny Wychfield for a fun-filled day of activities and socialising. We hope everyone had as much fun as our cover star! During the year, we also launched the improved College website, received planning permission for a new music practice and performance space in Avery Court, and welcomed back several alumni for their weddings in College. Your generous donations continue to have a positive impact on the lives of students and the fabric of College; thank you for your continued support. Kathryn Greaves Alumni Communications Officer Stay in touch with the College network: 32 Alumni @TrinityHallCamb News inside Reports from our Officers 2 The Master 2 The Bursar 4 The Senior Tutor 6 The Graduate Tutor 8 The Admissions Tutor 10 The Dean 11 The Development Director 12 The Junior Bursar 14 The Head of Conference and Catering Services 15 The Librarian 16 The Director of Music 17 College News 18 The JCR President’s Report 20 The MCR President’s Report 21 Student Reports 22 News of Fellows and Staff 26 Seminars and Lectures 28 Fundraising 30 18 Alumni News 32 THA Secretary’s Report 34 College News Alumni News 36 In Memoriam 38 2017/18 Information 40 List of Fellows 42 College Statistics 46 List of Donors 50 Get involved 59 Thank you to all who have contributed to this edition of the Trinity Hall Review. -

The Region's Best Guide to What's On

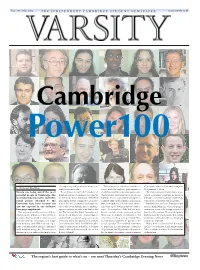

Issue 591, 16 Jan 2004 THE INDEPENDENT CAMBRIDGE STUDENT NEWSPAPER www.varsity.co.uk Cambridge Power100 of computing and security in an increas- The list was researched in a number of 47 percent of the total, women comprise Jo Hartley and Daud Khan ingly insecure world. ways, both through an open appeal to 23.4 percent of those. Varsity can today unveil the most From James Crawford, President of candidates and through investigation into This list reinforces Cambridge’s repu- powerful people in Cambridge. The International Law Commission, to the ‘al- the brightest and brightest stars in our tation as premier scientific institution, most talented, innovative and influ- most famous’ Sarah Solemani, a West End bubble. It was a project that began in with 20% of the list made up of scientists, ential people attached to the performer, the list comprises a cross sec- summer 2003, and has been constantly in with seven of these Nobel Laureates. University have been scouted out tion of fellows, academics and students, flux, with updates as to who was achiev- Student-wise, we have Entrepreneurs and are exposed in our exclusive all of whose credentials had to undergo ing what up to the moment we went to such as Azim Mumtaz, who is hoping to four page supplement. rigorous analysis in order to be kept on the press. As compilers of the list, we were secure easy to use solar energy systems for The internationally acclaimed Ross list. The list includes Nobel Laureates and keen to include a wide cross section, but third world countries. -

Le Centre Pompidou De Paris : La Réalisation D’Un Grand Projet Artistique Et Culturel : Les Nouveaux Usages De La Démocratisation De L’Art Jian-Chung Tan

Le centre Pompidou de Paris : la réalisation d’un grand projet artistique et culturel : les nouveaux usages de la démocratisation de l’art Jian-Chung Tan To cite this version: Jian-Chung Tan. Le centre Pompidou de Paris : la réalisation d’un grand projet artistique et culturel : les nouveaux usages de la démocratisation de l’art. Art et histoire de l’art. Université de Lorraine, 2016. Français. NNT : 2016LORR0244. tel-01752394 HAL Id: tel-01752394 https://hal.univ-lorraine.fr/tel-01752394 Submitted on 4 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. AVERTISSEMENT Ce document est le fruit d'un long travail approuvé par le jury de soutenance et mis à disposition de l'ensemble de la communauté universitaire élargie. Il est soumis à la propriété intellectuelle de l'auteur. Ceci implique une obligation de citation et de référencement lors de l’utilisation de ce document. D'autre part, toute contrefaçon, plagiat, reproduction illicite encourt une poursuite pénale. Contact : [email protected] LIENS Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle. articles L 122. 4 Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle. articles L 335.2- L 335.10 http://www.cfcopies.com/V2/leg/leg_droi.php http://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/infos-pratiques/droits/protection.htm UNIVERSITÉ DE LORRAINE École doctorale Fernand Braudel Laboratoire Lorrain de Sciences Sociales 2L2S LE CENTRE POMPIDOU DE PARIS. -

AGNÈS THURNAUER «FRANCINE PICABIA» Exposition Personnelle AU CCC DE TOURS Du 17 MARS 2007 AU 24 FÉVRIER 2008

dossier documentaire et pédagogique AGNÈS THURNAUER «FRANCINE PICABIA» EXPOSITION PERSONNELLE AU CCC DE TOURS DU 17 MARS 2007 AU 24 FÉVRIER 2008 55 RUE MARCEL TRIBUT - 37000 TOURS - T (+33/0) 2 47 66 50 00 - F (+33/0) 2 47 61 60 24 CONtact : SANDRA ÉMONET / EMAIL : [email protected] SITE : WWW.CCC-ART.COM SO MMAIRE L’EXPOSITION : «Francine Picabia » TEXTE DE PRÉSENTATION 3 VUES DE L’EXPOSITION 4 DES ANGLES D’APPROCHES & PISTES D’ATELIERS IMAGE ET LANGAGE 5 UNE GALERIE DE PORTRAITS 6 LA COULEUR 9 > lien avec la thématique «Couleurs» des actions éducatives de la Ville de Tours L’ARTISTE : AGNÈS THURNAUER BIOGRAPHIE & BIBLIOGRAPHIE 12 ARTICLES DE PRESSE 13 L’ACCUEIL AU CCC : À VOTRE SERVICE DES ÉCOLES ET COLLÈGES RURAUX AU CCC 16 MÉMO DES SERVICES ET CONTACTS + AGENDA 18 55 RUE MARCEL TRIBUT - 37000 TOURS - T (+33/0) 2 47 66 50 00 - F (+33/0) 2 47 61 60 24 p. CONtact : SANDRA ÉMONET / EMAIL : [email protected] > SITE : WWW.CCC-ART.COM PRÉSENTATION DE L’EXPOSITION «FRANCINE PICABIA» EXPOSITION PERSONNELLE D’AgNÈS THURNAUER AU CCC DE TOURS / DU 17 MARS 2007 AU 24 FÉVRIER 2008 « Représenter /…/, c’est donner forme à des questions. Or donner forme à des questions avec des mots et en rendre compte de façon plastique ou picturale sont des choses très différentes. Représenter une question, c’est se permettre de regarder cette question comme un paysage. A partir du moment où l’on peut regarder la question, on y répond sans l’arrêter, on chemine avec elle. -

International Student Guide Pre-Arrival and Orientation Information Welcome from the International Student Team Travelling to Cambridge

International Student Guide Pre-arrival and orientation information Welcome from the International Student Team Travelling to Cambridge By Air This pre-arrival and orientation guide has been produced for students who are coming to study at Cambridge from outside the UK. It provides practical Cambridge is served by five main airports: Stansted (the closest), Heathrow, guidance on coming to live and study in Cambridge from an international student Gatwick, City and Luton. perspective and its intention is to complement other sources of guidance you are likely to receive as part of your induction from, for example, your College and the From Stansted: take a direct train to Cambridge which takes 35 minutes and Cambridge University Students Union (CUSU / iCUSU). costs around £15 one way. For further information visit www.stanstedairport.com/ to-and-from-the-airport/train/ Each year the University of Cambridge welcomes over 800 new undergraduate and From Heathrow: take a National Express coach to Cambridge which stops at 2500 graduate international students from over 130 different countries. Coming Parkside next to Parker’s Piece (park). Check journey time and ticket costs at www. to live and study in Cambridge can be both an exciting and daunting prospect but nationalexpress.com Alternatively, you can take the train - first take the Piccadilly there is a lot of support available to you. Line on the London Underground to King’s Cross Station and then a train to Cambridge. Check journey time and costs at www.nationalrail.co.uk The International Student Team (IST), based in the Academic Division, provides specialist support to international students. -

TRINITY HALL NEWSLETTER MICHAELMAS 2005 Newsletter MICHAELMAS 2005

TRINITY HALL CAMBRIDGE TRINITY HALL NEWSLETTER MICHAELMAS 2005 Newsletter MICHAELMAS 2005 The Trinity Hall Newsletter is published by the College. Printed by Cambridge Printing, the printing business of Cambridge University Press. www.cambridgeprinting.org Thanks are extended to all the contributors and to the Editor, Liz Pentlow Trinity Hall Newsletter MICHAELMAS 2005 College Reports ............................................................................ 3 Trinity Hall Association & Alumni Reports............................. 29 Lectures & Research .................................................................. 45 Student Activities, Societies & Sports ...................................... 49 The Gazette ................................................................................ 61 Reply Slips & Keeping in Touch ........................... Cream Section Section One College Reports 3 The Master Professor Martin Daunton MA PhD LittD FRHistS FBA Professor of Economic History Fellows and Fellow-Commoners Professor Thomas Körner MA PhD ScD Vice Master, Graduate Mentor, Staff Fellow and Director of Studies in Mathematics; Professor of Fourier Analysis Professor Colin Austin MA DPhil FBA Praelector, Graduate Mentor, Professorial Fellow and Director of Studies in Classics; Professor of Greek Mr David Fleming MA LLB Tutor and Staff Fellow in Law Dr David Moore MA PhD Staff Fellow and Director of Studies in Engineering; University Reader in Engineering Dr Peter Hutchinson MA PhD LittD Staff Fellow and Director of Studies in Modern -

Once a Caian... 9-12 Issue 12

EVENTS AND REUNIONS FOR 2 014 /15 ISSUE 14 MICHAELMAS 2014 GONVILLE & CAIUS COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE Development Campaign Board Meeting . Thursday 2 October Caius Club London Dinner . Friday 3 October Michaelmas Full Term begins . Tuesday 7 October Caius Foundation Board Meeting . Wednesday 5 November New York Reception . Wednesday 5 November Patrons of the Caius Foundation Dinner . Wednesday 5 November Commemoration of Benefactors Lecture, Service & Feast . Sunday 16 November First Christmas Carol Service (6pm) . Wednesday 3 December Second Christmas Carol Service (4.30pm) . Thursday 4 December Michaelmas Full Term ends . Friday 5 December Varsity Rugby Match . Thursday 11 December Lent Full Term begins . Tuesday 13 January Development Campaign Board Meeting . Thursday 26 February Second Year Parents’ Hall . Thursday 12 & Friday 13 March Lent Full Term ends . Friday 13 March Telephone Campaign begins . Saturday 14 March MAs’ Dinner . Friday 20 March Annual Gathering (1972, 1973 & 1974) . Friday 27 March Hong Kong Reception . Monday 13 April Hong Kong Dinner for Members of the Court of Benefactors . Monday 13 April Singapore Reception . Thursday 16 April Easter Full Term begins . Tuesday 21 April Stephen Hawking Circle “50 Years a Fellow” Celebration . Saturday 30 May Easter Full Term ends . Friday 12 June May Week Party for Benefactors . Saturday 13 June Caius Club May Bumps Event . Saturday 13 June Graduation Lunch . Thursday 25 June Annual Gathering (up to & including 1963) . Tuesday 30 June Admissions Open Days . Thursday 2 & Friday 3 July