Webobjects Developer's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

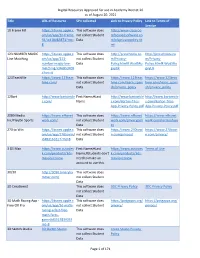

Digital Resources Approved for Use in Academy District 20 As Of

Digital Resources Approved for use in Academy District 20 as of August 20, 2021 Title URL of Resource SPII collected Link to Privacy Policy Link to Terms of Service 10 Frame Fill https://itunes.apple.c This software does http://www.classroo om/us/app/10-frame- not collect Student mfocusedsoftware.co fill/id418083871?mt= Data m/cfsprivacypolicy.ht 8 ml 123 NUMBER MAGIC https://itunes.apple.c This software does http://preschoolu.co http://preschoolu.co Line Matching om/us/app/123- not collect Student m/Privacy- m/Privacy- number-magic-line- Data Policy.html#.Wud5Ro Policy.html#.Wud5Ro matching/id46853409 gvyUk gvyUk 4?mt=8 123TeachMe https://www.123teac This software does https://www.123teac https://www.123teac hme.com/ not collect Student hme.com/learn_spani hme.com/learn_spani Data sh/privacy_policy sh/privacy_policy 12Bart http://www.bartontile First Name;#Last http://www.bartontile http://www.bartontile s.com/ Name s.com/Barton-Tiles- s.com/Barton-Tiles- App-Privacy-Policy.pdf App-Privacy-Policy.pdf 2080 Media https://www.nfhsnet This software does https://www.nfhsnet https://www.nfhsnet Inc/PlayOn Sports work.com/ not collect Student work.com/privacypoli work.com/termsofuse Data cy 270 to Win https://itunes.apple.c This software does https://www.270towi https://www.270towi om/us/app/270towin/ not collect Student n.com/privacy/ n.com/privacy/ id483161617?mt=8 Data 3 DS Max https://www.autodes First Name;#Last https://www.autodes Terms of Use k.com/products/3ds- Name;#Students don't k.com/products/3ds- max/overview need to make an max/overview account to use this. -

Appendix a the Ten Commandments for Websites

Appendix A The Ten Commandments for Websites Welcome to the appendixes! At this stage in your learning, you should have all the basic skills you require to build a high-quality website with insightful consideration given to aspects such as accessibility, search engine optimization, usability, and all the other concepts that web designers and developers think about on a daily basis. Hopefully with all the different elements covered in this book, you now have a solid understanding as to what goes into building a website (much more than code!). The main thing you should take from this book is that you don’t need to be an expert at everything but ensuring that you take the time to notice what’s out there and deciding what will best help your site are among the most important elements of the process. As you leave this book and go on to updating your website over time and perhaps learning new skills, always remember to be brave, take risks (through trial and error), and never feel that things are getting too hard. If you choose to learn skills that were only briefly mentioned in this book, like scripting, or to get involved in using content management systems and web software, go at a pace that you feel comfortable with. With that in mind, let’s go over the 10 most important messages I would personally recommend. After that, I’ll give you some useful resources like important websites for people learning to create for the Internet and handy software. Advice is something many professional designers and developers give out in spades after learning some harsh lessons from what their own bitter experiences. -

Webobjects Technical Overview

Session 401 WebObjects Technical Overview Steve Hayman Systems Engineer, Apple iServices 1 Apple Confidential 6/28/00 Introduction • Understand the WO architecture • See the tools, frameworks, and development process in action 2 Apple Confidential 6/28/00 What You’ll Learn • WO Tools • WO Frameworks • WO Deployment • Understand the titles of the other WO sessions 406—Rapid Development with Direct to Java Client 3 Apple Confidential 6/28/00 What WebObjects Does • It’s an Application Server • Who invented that term anyway? • It’s more than just that – Developer Tools – Pre-written objects (Frameworks) The best part! – Runtime environment – Monitoring and control tools 4 Apple Confidential 6/28/00 For Instance Java Clients Web Browsers Data Services Web Servers Distributed Objects Data Sources 5 Apple Confidential 6/28/00 Who WebObjects Is For • Developers • Very powerful • Steep learning curve • But that’s OK 6 Apple Confidential 6/28/00 WebObjects Works With… • Java. Objective-C. WebScript • Databases—Oracle, Informix, Sybase, SQL Server, LDAP, OpenBase, FrontBase, … • Mainframes—CORBA, 3270 screen-scraping • Different UIs—HTML, WAP, PDF, XML • Most web servers—Apache, Netscape, IIS • Lots of 3rd-party objects and APIs • Open open open open open open open open 7 Apple Confidential 6/28/00 Where You Can Use WebObjects • Develop on Mac OS X, Mac OS X Server, or Windows NT • Deploy on OS X, OS X Server, NT, Solaris, HP/UX, Linux – (Note: database support varies by platform) • Mix and match as needed • Start small and grow bigger 8 Apple Confidential -

Plugin Tapestry

PlugIn Tapestry Autor @picodotdev https://picodotdev.github.io/blog-bitix/ 2019 1.4.2 5.4 A tod@s l@s programador@s que en su trabajo no pueden usar el framework, librería o lenguaje que quisieran. Y a las que se divierten programando y aprendiendo hasta altas horas de la madrugada. Non gogoa, han zangoa Hecho con un esfuerzo en tiempo considerable con una buena cantidad de software libre y más ilusión en una región llamada Euskadi. PlugIn Tapestry: Desarrollo de aplicaciones y páginas web con Apache Tapestry @picodotdev 2014 - 2019 2 Prefacio Empecé El blog de pico.dev y unos años más tarde Blog Bitix con el objetivo de poder aprender y compartir el conocimiento de muchas cosas que me interesaban desde la programación y el software libre hasta análisis de los productos tecnológicos que caen en mis manos. Las del ámbito de la programación creo que usándolas pueden resolver en muchos casos los problemas típicos de las aplicaciones web y que encuentro en el día a día en mi trabajo como desarrollador. Sin embargo, por distintas circunstancias ya sean propias del cliente, la empresa o las personas es habitual que solo me sirvan meramente como satisfacción de adquirir conocimientos. Hasta el día de hoy una de ellas es el tema del que trata este libro, Apache Tapestry. Para escribir en el blog solo dependo de mí y de ninguna otra circunstancia salvo mi tiempo personal, es com- pletamente mío con lo que puedo hacer lo que quiera con él y no tengo ninguna limitación para escribir y usar cualquier herramienta, aunque en un principio solo sea para hacer un ejemplo muy sencillo, en el momento que llegue la oportunidad quizá me sirva para aplicarlo a un proyecto real. -

Ish Case Study Ish Hires Objectstyle to Modernise Its Student Management Platform, Grows Business by 300% in the Course of 5 Years

ish Case Study ish hires ObjectStyle to modernise its student management platform, grows business by 300% in the course of 5 years ish is the company behind onCourse™, a widely-used software platform Company: that allows colleges and short course providers to manage enrolments, curricula, student grades, and other aspects of the learning/teaching Company name: ish process. Industry: Education The platform serves dozens of educational entities in Australia (including Year founded: 2002 such heavyweights as The University of Sydney, Sydney Community College, NIDA, Coffee School, Power Training Services WA...), and is one of Location: Australia the most popular solutions in the market. Website: http://ish.com.au Challenge In the year 2011, the onCourse platform was 5 years old and needed major refactoring to modernise the code, improve performance and set a new direction for future development. ish wanted to revamp the content management system and the student/tutor portal components as well as make it easy to add new features. ish had originally chosen WebObjects as a web platform and that tool had been largely abandoned, so a change of technology was needed. ish was also picking up big new customers, including universities, that required the production servers to be able to scale with increased volume. Solution 1. Apache Tapestry-based custom CMS. Colleges received an improved, more feature-rich and flexible content management system (CMS) which they could use for publishing catalogues, individual courses, promotions, and other CMS elements. The revamped CMS provided additional space for customizing the look-and-feel as well as the layout of the materials that colleges put up on their websites. -

VIVO: a Semantic Approach to Scholarly Networking and Discovery

VIVO A Semantic Approach to Scholarly Networking and Discovery Synthesis Lectures on Semantic Web: Theory and Technology Editors James Hendler, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Ying Ding, Indiana University Synthesis Lectures on the Semantic Web: Theory and Application is edited by James Hendler of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Whether you call it the Semantic Web, Linked Data, or Web 3.0, a new generation of Web technologies is offering major advances in the evolution of the World Wide Web. As the first generation of this technology transitions out of the laboratory, new research is exploring how the growing Web of Data will change our world. While topics such as ontology-building and logics remain vital, new areas such as the use of semantics in Web search, the linking and use of open data on the Web, and future applications that will be supported by these technologies are becoming important research areas in their own right. Whether they be scientists, engineers or practitioners, Web users increasingly need to understand not just the new technologies of the Semantic Web, but to understand the principles by which those technologies work, and the best practices for assembling systems that integrate the different languages, resources, and functionalities that will be important in keeping the Web the rapidly expanding, and constantly changing, information space that has changed our lives. Topics to be included: • Semantic Web Principles from linked-data to ontology design • Key Semantic Web technologies and algorithms • Semantic Search -

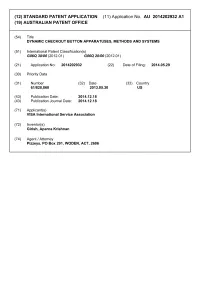

Application No: 2014202932 (22) Date of Filing: 2014.05.29 (30) Priority Data (31) Number (32) Date (33) Country 61/828,868 2013.05.30 US

(12) STANDARD PATENT APPLICATION (11) Application No. AU 2014202932 A1 (19) AUSTRALIAN PATENT OFFICE (54) Title DYNAMIC CHECKOUT BUTTON APPARATUSES, METHODS AND SYSTEMS (51) International Patent Classification(s) G06Q 30/00 (2012.01) G06Q 20/00 (2012.01) (21) Application No: 2014202932 (22) Date of Filing: 2014.05.29 (30) Priority Data (31) Number (32) Date (33) Country 61/828,868 2013.05.30 US (43) Publication Date: 2014.12.18 (43) Publication Journal Date: 2014.12.18 (71) Applicant(s) VISA International Service Association (72) Inventor(s) Girish, Aparna Krishnan (74) Agent / Attorney Pizzeys, PO Box 291, WODEN, ACT, 2606 Attorney Docket No.: 543US02I236474-888028 48 2014 May ABSTRACT 29 The DYNAMIC CHECKOUT BUTTON APPARATUSES, METHODS AND SYSTEMS (“DCB”) transforms product page checkout request input and user identification input via DCB components such as offer/discount determination component and checkout button embedding component, into dynamic checkout button outputs. 2014202932 Attorney Docket No.: 543US02I236474-888028 1 2014 May DYNAMIC CHECKOUT BUTTON APPARATUSES, METHODSAND 29 SYSTEMS [0001] This application claims priority to United States provisional patent application serial no. 61/828,868, filed May 30, 2013, entitled “DYNAMIC CHECKOUT BUTTON APPARATUSES, METHODS AND SYSTEMS. The entire contents of the aforementioned application is expressly incorporated by reference herein. 2014202932 [0002] This application for letters patent disclosure document describes inventive aspects directed at various novel innovations (hereinafter “disclosure”) and contains material that is subject to copyright, mask work, and/or other intellectual property protection. The respective owners of such intellectual property have no objection to the facsimile reproduction of the disclosure by anyone as it appears in published Patent Office file/records, but otherwise reserve all rights. -

Towards Left Duff S Mdbg Holt Winters Gai Incl Tax Drupal Fapi Icici

jimportneoneo_clienterrorentitynotfoundrelatedtonoeneo_j_sdn neo_j_traversalcyperneo_jclientpy_neo_neo_jneo_jphpgraphesrelsjshelltraverserwritebatchtransactioneventhandlerbatchinsertereverymangraphenedbgraphdatabaseserviceneo_j_communityjconfigurationjserverstartnodenotintransactionexceptionrest_graphdbneographytransactionfailureexceptionrelationshipentityneo_j_ogmsdnwrappingneoserverbootstrappergraphrepositoryneo_j_graphdbnodeentityembeddedgraphdatabaseneo_jtemplate neo_j_spatialcypher_neo_jneo_j_cyphercypher_querynoe_jcypherneo_jrestclientpy_neoallshortestpathscypher_querieslinkuriousneoclipseexecutionresultbatch_importerwebadmingraphdatabasetimetreegraphawarerelatedtoviacypherqueryrecorelationshiptypespringrestgraphdatabaseflockdbneomodelneo_j_rbshortpathpersistable withindistancegraphdbneo_jneo_j_webadminmiddle_ground_betweenanormcypher materialised handaling hinted finds_nothingbulbsbulbflowrexprorexster cayleygremlintitandborient_dbaurelius tinkerpoptitan_cassandratitan_graph_dbtitan_graphorientdbtitan rexter enough_ram arangotinkerpop_gremlinpyorientlinkset arangodb_graphfoxxodocumentarangodborientjssails_orientdborientgraphexectedbaasbox spark_javarddrddsunpersist asigned aql fetchplanoriento bsonobjectpyspark_rddrddmatrixfactorizationmodelresultiterablemlibpushdownlineage transforamtionspark_rddpairrddreducebykeymappartitionstakeorderedrowmatrixpair_rddblockmanagerlinearregressionwithsgddstreamsencouter fieldtypes spark_dataframejavarddgroupbykeyorg_apache_spark_rddlabeledpointdatabricksaggregatebykeyjavasparkcontextsaveastextfilejavapairdstreamcombinebykeysparkcontext_textfilejavadstreammappartitionswithindexupdatestatebykeyreducebykeyandwindowrepartitioning -

(2) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0261625A1 Cape Et Al

US 20150261625A1 (19) United States (2) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0261625A1 Cape et al. (43) Pub. Date: Sep. 17, 2015 (54) TECHNIQUES FOR MESSAGE Publication Classification RETRANSMISSION MECHANISM (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: IEX Group, Inc, New York, NY (US) G{}6F II/14 (2006.01) (52) U.S. CI. (72) Inventors: James Michael Cape, New York, NY CPC .................................. G06F II/I469 (2013.01) (US); Robert Park, New York, NY (US); Allen Zhang, Princeton, NJ (US); Zoran Perkov, Brooklyn, NY (US); (57) ABSTRACT Lieting Yu, Warren, NJ (US); Prerak Pukhraj Sanghvi, Jersey City, NJ (US); Beau Tateyama, New York, NY (US); Embodiments of the Message Retransmission Mechanism Constantine Sokoloff, Jersey City, NJ Apparatuses, Methods and Systems (“MRM”) transform (US); Eric Quinlan, Norwalk, CT (US) application requests for message journals via MRM compo ments into expedited access to segmented message streams. In (21) Appl. No.: 14/644,606 one implementation, the MRM may obtain message journal (22) Filed: Mar. 11, 2015 of messages written by applications during system operations and divide up the message obtained from the complete mes Related U.S. Application Data sage journal into message segments. In some implementa (60) Provisional application No. 61/951,364, filed on Mar. tions, the MRM may provide recovering applications access 11, 2014, provisional application No. 61/951,390, to said message segments for expedited message consump filed on Mar. 11, 2014. tion. Application Afailed earlier. So it is trying MRM provides message retransmission 1.01 to catch upon a? the activities the other through segmentedjournals, andlor through apps have been up to. -

A Comparison of Web Development Technologies: Webobjects Vs. ASP.NET

A Comparison of Web Development Technologies: WebObjects vs. ASP.NET By: Adnan Al-Ghourabi Chairman: Dr. Axel Schreiner Reader: Dr. James Heliotis Department of Computer Science Rochester Institute of Technology Rochester, NY 14623 1. Introduction One of the major disadvantages of html is the fact that it is static; any modification requires editing the html file. This is a cumbersome task, as websites grow bigger in content and complexity. The advent of server-scripting languages was targeted at solving the deficiencies of html by providing dynamic web content that is usually database-driven. There are several languages that have been tailored for web development: JSP, which is based on Sun’s Java language; ASP, Microsoft’s early server-side scripting language; PHP and others. These languages hold considerable shares of web application development projects for both the Windows and Unix/Linux platforms. With the introduction of the .NET framework in late 2000, ASP has been tremendously improved to take advantage of object oriented programming, and have recently become the dominant development language of choice for web applications on windows platforms. Johnson & Johnson, for example, has recently launched two websites developed in ASP.NET, changing a long-followed trend of using JSP. Intranet applications have also been developed in ASP.NET. There is also the less heard about: WebObjects. WebObjects is a system that consists of a number of development and deployment tools, and a set of frameworks to develop server applications. WebObjects applications are Java based and therefore can be deployed on a variety of platforms1. WebObjects was first created by NeXT in late 80’s and was based on Objective-C. -

Application Performance Management

Application Performance Management AppDynamics Pro Documentation Version 4.1.7 Page 1 Instrument Applications . 7 Install and Administer Agents . 7 Connect the Controller and Agents . 8 Business Application, Tier, and Node Naming . 11 Metrics Limits . 12 Manage App Agents . 14 Historical and Disconnected Nodes . 16 Agent Log Files . 18 Request Agent Log Files . 24 App Agent Node Properties . 26 App Agent Node Properties Reference . 31 Dynamic Language Agent Proxy . 58 Instrument Java Applications . 61 Java Supported Environments . 64 Install the Java Agent . 78 Java Agent Configuration Properties . 83 Instrument JVMs in a Dynamic Environment . 95 Use System Properties for Java Agent Settings . 96 Use Environment Variables for Java Agent Settings . 98 Instrument JVMs Started by Batch or Cron Jobs . 99 Instrument JVMs in Restricted Environments . 100 Automate Java Agent Deployment . 101 Instrument Apple WebObjects Applications . 101 Java Server-Specific Installation Settings . 102 Apache Cassandra Startup Settings . 102 Apache Tomcat Startup Settings . 103 Coherence Startup Settings . 105 GlassFish Startup Settings . 105 IBM WebSphere and InfoSphere Startup Settings . 107 JBoss and Wildfly Startup Settings . 111 Jetty Startup Settings . 120 Mule ESB Startup Settings . 121 Oracle WebLogic Startup Settings . 122 OSGi Infrastructure Configuration . 125 Resin Startup Settings . 127 Solr Startup Settings . 129 Standalone JVM Startup Settings . 129 Tanuki Service Wrapper Settings . 130 Tibco ActiveMatrix BusinessWorks Service Engine Settings . 130 webMethods Startup Settings . 131 Sensitive Data Filters . 132 IBM Java Agent . 133 Enable SSL for Java . 134 Java Agent Directory Structure . 137 Moving Java Nodes Between Applications or Tiers . 139 Upgrade the Java Agent . 139 Uninstall the Java Agent . 141 Tune Java Agent Performance . -

Enviroinfo Brno 2005 Layout Rules

Evaluation categorizes, technologies decision for a Composite Environmental Performance Indicators (LWC-EPI) solution Naoum Jamous1, Frederik Kramer1, Gamal Kassem1 Abstract Rapid environmental changes have necessitated a closer and more critical review of current environmental policies. In light of a myopic tendency to focus on short- to medium-term objectives within organizations, environmental is- sues are usually not given full attention. In this regard, recommendation- or dashboard-like systems are useful to in- crease the awareness of management as to the impact of their decisions on the environment on a more frequent and cost-effective basis. However, the role of current environmental management information systems (EMIS) in provid- ing organizations with the information enabling them to assess the current impact of their processes and operations on the environment has been given more prominence. Information technology is changing business in ever shortening cycles. Especially with the success of the Java plat- form, the standardization through the i386 hardware platform and last but not least the rivalry introduced by the Free, Libre and Open Source Software (F/LOSS) paradigm a sheer inconceivable amount of programming languages, inte- grated development environments, design patterns and programming frameworks have been disseminated. In this paper, we will start with a state of the art of the available tools support providing dashboard-type solutions to control and monitor the EPI’s in an organization, which may lead to reduce the gap between estimated values and current running values for environment on a more frequent basis than a mere yearly review. Furthermore, we will propose an evaluation categorizes to be used as a methodology to take the technologies decisions.