Archaeological Assessment Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern Cape Rural Transport Strategy

Eastern Cape Rural Transport Strategy Baseline Conditions October 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 3 1.1 Aims and objectives of the Provincial Rural Transport Plan 3 1.2 Aims and objectives of this Baseline Report 4 1.3 Structure of the Baseline Report 4 2. POLICY OVERVIEW 5 2.1 Legislative and other mandates 5 2.2Provincial Growth and Development Plan (PGDP) 7 2.3 Integrated and Sustainable Rural Development Programme (ISRDP) 8 2.4 Integrated Development Planning (IDP) 10 2.5 White Paper on Spatial Planning and Land Use Management 11 2.6 Transport policies 11 3. TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE 14 3.1 The Current Network 14 3.2 Backlogs 18 3.3 Maintenance 21 3.4 Funding 30 4. RURAL TRANSPORT SERVICES 38 2 4.1. 4.1 Introduction 38 4.2. 4.2 Rural Public Transport: Buses 39 4.3. 4.3 Rural Public Transport: Taxis 46 4.4. 4.4 Rail transport 48 4.5. 4.5 Special Needs Transport 50 4.6. 4.6 Affordability of rural public transport 51 4.7. 4.7 Safety and Security on Rural Public Transport 51 4.8. 4.8 Rural Freight Services 52 4.9. 4.9 Transport issues related to selected rural economic drivers 56 4.10. 4.10 Intermediate Means of Transport 62 4.11. 4.11 Transporting people and their goods in Port St Johns: A case study 66 4.12. 5. INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW 69 5.1 Scope of Rural Transport 69 5.2 Institutional Responsibility 71 5.3 Inter-agency cooperation and linkages 81 6. -

Lukhanji Local Municipality

LUKHANJI LOCAL MUNICIPALITY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN REVIEW - 2015 / 2016 1. Mayor’s Foreword ..................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. 6 CHAPTER 1 - PREPLANNING ............................................................................................................................. 8 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 8 2. LEGAL FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................................. 8 3. PRE-PLANNING .......................................................................................................................................... 9 1) Organisational Arrangements in the IDP Development and Review Processes ................................................... 9 . Role players ............................................................................................................................................ 9 2) Roles and Responsibilities of Each Role Player .................................................................................... 10 3) Approved schedule for the IDP / PMS and Budget REVIEW PROCESS PLAN – 2014 / 2015Error! Bookmark not defined. Chapter 2 Situational -

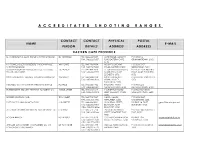

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Crime in the Rural District of Stellenbosch

CRIME IN THE RURAL DISTRICT OF STELLENBOSCH: A CASE STUDY ARLENE JOY DAVIDS Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. SUPERVISOR: PROF. HL ZIETSMAN DECEMBER 2004 SUMMARY One of the most distressing criminal activities has been the attacks on farmers since 1994 and for many years now our farming community has been plagued by these senseless acts of brutality. Since the early nineties there has been a steady increase in the occurrence of farm attacks in our country and the rising incidence of violent crimes on farms and smallholdings in South Africa has become a cause for great concern. The farming community in South Africa has a very significant function in the economy of the country as producers of food and providers of jobs and other commodities required by various other industries, such as the mining industry. They render an indispensable service to our country and therefore we have to ensure that this community receives the necessary safeguarding that is so desperately needed at this time. Farm attacks are occurring at alarming rates in South Africa, the Western Cape, and recently also in the Stellenbosch district. The phenomenon of farm attacks needs to be analysed in the context of the crime situation in general. The underlying reasons for crime are diverse and many, and need to be taken into account when interpreting the causes of crime in South Africa. To ensure that this research endeavour has practical value for the various parties involved in protecting rural communities, crime hotspots and circumstances in which crime occur were identified and used as a tool to provide the necessary protection and mobilisation of forces for these areas. -

Heritage Scan of the Sandile Water Treatment Works Reservoir Construction Site, Keiskammahoek, Eastern Cape Province

HERITAGE SCAN OF THE SANDILE WATER TREATMENT WORKS RESERVOIR CONSTRUCTION SITE, KEISKAMMAHOEK, EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE 1. Background and Terms of Reference AGES Eastern Cape is conducting site monitoring for the construction of the Sandile Water Treatment Works Reservoir at British Ridge near Keiskammahoek approximately 30km west of King Williamstown in the Eastern Cape Province. Amatola Water is upgrading the capacity of the Sandile WTW and associated bulk water supply infrastructure, in preparation of supplying the Ndlambe Bulk Water Supply Scheme. Potentially sensitive heritage resources such as a cluster of stone wall structures were recently encountered on the reservoir construction site on a small ridge and the Heritage Unit of Exigo Sustainability was requested to conduct a heritage scan of the site, in order to assess the site and rate potential damage to the heritage resources. The conservation of heritage resources is provided for in the National Environmental Management Act, (Act 107 of 1998) and endorsed by section 38 of the National Heritage Resources Act (NHRA - Act 25 of 1999). The Heritage Scan of the construction site attempted established the location and extent of heritage resources such as archaeological and historical sites and features, graves and places of religious and cultural significance and these resources were then rated according to heritage significance. Ultimately, the Heritage Scan provides recommendations and outlines pertaining to relevant heritage mitigation and management actions in order to limit and -

National Liquor Authority Register

National Liquor Register Q1 2021 2022 Registration/Refer Registered Person Trading Name Activities Registered Person's Principal Place Of Business Province Date of Registration Transfer & (or) Date of ence Number Permitted Relocations or Cancellation alterations Ref 10 Aphamo (PTY) LTD Aphamo liquor distributor D 00 Mabopane X ,Pretoria GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 12 Michael Material Mabasa Material Investments [Pty] Limited D 729 Matumi Street, Montana Tuine Ext 9, Gauteng GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 14 Megaphase Trading 256 Megaphase Trading 256 D Erf 142 Parkmore, Johannesburg, GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 22 Emosoul (Pty) Ltd Emosoul D Erf 842, 845 Johnnic Boulevard, Halfway House GP 2016-10-07 N/A N/A Ref 24 Fanas Group Msavu Liquor Distribution D 12, Mthuli, Mthuli, Durban KZN 2018-03-01 N/A 2020-10-04 Ref 29 Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd D Erf 19, Vintonia, Nelspruit MP 2017-01-23 N/A N/A Ref 33 Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd D 117 Foresthill, Burgersfort LMP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 34 Media Active cc Media Active cc D Erf 422, 195 Flamming Rock, Northriding GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 52 Ocean Traders International Africa Ocean Traders D Erf 3, 10608, Durban KZN 2016-10-28 N/A N/A Ref 69 Patrick Tshabalala D Bos Joint (PTY) LTD D Erf 7909, 10 Comorant Road, Ivory Park GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 75 Thela Management PTY LTD Thela Management PTY LTD D 538, Glen Austin, Midrand, Johannesburg GP 2016-04-06 N/A 2020-09-04 Ref 78 Kp2m Enterprise (Pty) Ltd Kp2m Enterprise D Erf 3, Cordell -

WMA12: Mzimvubu to Keiskamma Water Management Area

DEPARTMENT OF WATER AFFAIRS AND FORESTRY DIRECTORATE OF OPTIONS ANALYSIS LUKANJI REGIONAL WATER SUPPLY FEASIBILITY STUDY APPENDIX 2 ECOLOGICAL RESERVE (QUANTITY) ON THE KEI RIVER PREPARED BY IWR Source-to-Sea P O Box 122 Persequor Park 0020 Tel : 012 - 349 2991 Fax : 012 - 349 2991 e-mail : [email protected] FINAL January 2006 Title : Appendix 2 : Ecological Reserve (Quantity) on the Kei River Authors : S Koekemoer and D Louw Project Name : Lukanji Regional Water Supply Feasibility Study DWAF Report No. : P WMA 12/S00/3108 Ninham Shand Report No. : 10676/3842 Status of Report : Final First Issue : February 2004 Final Issue : January 2006 Approved for the Study Team : …………………………………… M J SHAND Ninham Shand (Pty) Ltd DEPARTMENT OF WATER AFFAIRS AND FORESTRY Directorate : Options Analysis Approved for the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry by : A D BROWN Chief Engineer : Options Analysis (South) (Project Manager) L S MABUDA Director ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The following specialist contributed to and participated in the Kei Reserve Specialist meeting: Drew Birkhead Hydraulics Streamflow Solutions Anton Bok Fish Anton Bok & Associates Denis Hughes Hydrology IWR Rhodes Nigel Kemper Riparian Vegetation Integrated Environmental Assessments Neels Kleynhans Fish DWAF, RQS Delana Louw Process specialist IWR Source-to-Sea Jay O'Keeffe Facilitator IWR Rhodes Nico Rossouw Water quality Ninham Shand Consulting Services Christa Thirion Invertebrates DWAF, RQS Mandy Uys Invertebrates Laughing Waters Roy Wadeson Geomorphology Private DWAF (Resource Directed -

Music and Militarisation During the Period of the South African Border War (1966-1989): Perspectives from Paratus

Music and Militarisation during the period of the South African Border War (1966-1989): Perspectives from Paratus Martha Susanna de Jongh Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Professor Stephanus Muller Co-supervisor: Professor Ian van der Waag December 2020 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 29 July 2020 Copyright © 2020 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract In the absence of literature of the kind, this study addresses the role of music in militarising South African society during the time of the South African Border War (1966-1989). The War on the border between Namibia and Angola took place against the backdrop of the Cold War, during which the apartheid South African government believed that it had to protect the last remnants of Western civilization on the African continent against the communist onslaught. Civilians were made aware of this perceived threat through various civilian and military channels, which included the media, education and the private business sector. The involvement of these civilian sectors in the military resulted in the increasing militarisation of South African society through the blurring of boundaries between the civilian and the military. -

Provincial Gazette Igazethi Yephondo Provinsiale Koerant

PROVINCE OF THE EASTERN CAPE IPHONDO LEMPUMA KOLONI PROVINSIE OOS-KAAP Provincial Gazette Igazethi Yephondo Provinsiale Koerant BISHO/KING WILLIAM’S TOWN Vol: 28 5 Julie 2021 No: 4586 5 July 2021 N.B. The Government Printing Works will ISSN 1682-4555 not be held responsible for the quality of 04586 “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 455006 2 No. 4586 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE, 5 JULIE 2021 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. Contents Gazette Page No. No. No. GENERAL NOTICES • ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS 23 Removal of Restrictions in terms of the Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act, 2013 (Act 16 of 2013): Erf 2833, Newton Park, Port Elizabeth, Eastern Cape: Correction of general notice no. 19 of 2021 ..... 4586 3 24 Special Planning and Land Use Management Act (16/2013): Erf 1534, East London ....................................... 4586 3 PROVINCIAL NOTICES • PROVINSIALE KENNISGEWINGS 82 Eastern Cape Consumer Protection Act, 2018 (Act No. 3 of 2018): Draft Regulations in terms of the Act for public comment .................................................................................................................................................. 4586 4 83 Sea Shore Act (21/1935): Proposed Lease of a Site situated below the High-Water Mark of the Tyalumna River, Applicant: Susan Booth ............................................................................................................................ 4586 49 84 Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (16/2013): Erf 14608, Walmer (representing Portion A of Erf 7005, Walmer), Port Elizabeth, Eastern Cape .................................................................................................... 4586 50 85 Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (16/2013): Erf 30. -

Coal Capital: the Shaping of Social Relations in the Stormberg, 1880-1910

UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND FACULTY OF HUMANITIES SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY COAL CAPITAL: THE SHAPING OF SOCIAL RELATIONS IN THE STORMBERG, 1880-1910 PhD PAT GIBBS 330289 Supervisors: Professor Phillip Bonner Dr Noor Nieftaqodien Professor Anne Mager Port Elizabeth 2014 i Abstract This thesis is an analysis of the interaction of a variety of communities that coalesced around the coal fields in the environs of the town of Molteno in the Stormberg mountains, during the late Victorian period and the first decade of the 20th century. An influx of mining and merchant capitalists, bankers and financiers, skilled miners and artisans from overseas and Thembu labourers from across the Kei River flooded into what had been a quasi-capitalist world dominated mainly by Afrikaner stock farmers, some English farmers and Thembu and Khoi sharecroppers and labourers. It also examines the brief life-span of a coal mining enterprise, which initially held out the hope of literally fuelling South Africa’s industrial revolution, and its relationship with the economically and socially significant railway, which it drew into the area. This capitalisation of an early capitalist zone on the northern border of the Cape has demanded an analysis of the intersecting economies of mining, farming and urbanisation as well as of the race, class and ethnic formations generated by this interaction. In delineating the day-to-day minutiae of events, this thesis seeks to reveal a microcosmic view of the fortunes and identities of the associated communities and to present a distinctive, regional study of a hitherto unknown and early aspect of South Africa’s mineral revolution. -

National Norms and Standards for School Funding

.... Ir.._. r. t -.c.~ , ~1l"- ~ J' .•• A·· •• .. I =.;'''':. .. - "I" ]"' '. ·F.. .. .ir:' '.. .f, '- . ' ) '-\0 . ........:.....;...-:..,., " I y,_ .. ~ . P:~ . :l't~. - ~ ;'~I.-t£:£_ I II:IIIJAa. ~ 'P:.~. ';r~. I ,-~:, ~ ~f' ~!..r:i.l''liG. : c..' r'fIUI~OF?CItdOt'.' .', ~.~~l,:,';i~::.,;.~ .!i'o::~-? II ''' : "Ii < :I\; . 'oi.,;. :-~ '.:1'~ ~!.'r' ~' .., . .....~ . ~ ~ ' z. :",-t. .., .. l. ;~ -:'T--'" _; _'~Y' , 'JI,. " '." ~. ~" &. t.~i~ """To'I" . · ' 1 , ~ ~ ~.,..... ";1 , ' -, , .'I-}. ' "'?.J - ~ ~ .'LJ:;;.",l.1~~' -I ',,- . ~ \.I·- ~r' ~!I' .~ . r 1:0'" ... i' " 't: .r,. •...'. ,.,•• c; ,... .. f:.... .;:t _, _ .. ' . li t "". ' .. I ~y.,,~ .;~ _., ~ . ~ ,' "';\ · 1\ 1 _--. -r .J ~1, 1 ~~?}I'~ t1;r_ ~ .", ,,"" ~",~ ~-<~;: J;~ ' -~\.k. '~jr:'~~ I ~ ~ :f _ ~~~ .~ .:.I! :;ft~ ~~Lr;t.:r ~ AI · ··~~JI .\.\ '(; ~: .~ ~;r~_r:'" ~':~ ' ..,: ~~I; : ~_ f .-., r~ --"",! _ 4 _ ~~, _ , _ ,'f: .... J:.... • ••• -;., !. ...- ' " ..., ~ ~ ,. ~ : 401272 NKWENKWEZI SP SCHOOL Primary ,NKWENKWEZI AlA,ENGCOBO,5050 NGCOBOI 2 2051 R 740.00 600594 NOBUNTU JS SCHOOL Combined ,SIFONONDILE NA.. 5460 NGCOBOI 2 2641 R 740.00 600647 NYALASA JS SCHOOL Combined ,NYALASA AlA,CALA,5455 NGCOBOI 2 1951 R 740.00 400906 PAKAMISA SP SCHOOL Combined ,ELUCWECWE NA,ENGCOBO,5050 NGCOBOI 2 3521 R 740.00 600686 QIBA JS SCHOOL Combined QIBA NA"CALA,5455 NGCOBOI 2 1751 R 740.00 400949 QOBA PJS SCHOOL Combined ,ELUCWECWE AlA,ENGCOBO,5050 NGCOBOI 2 5051 R 740.00 400973 RYNO STATE AIDED SCHOOL Combined ,RYNO FARM,ELLlOT,5460 NGCOBOI 2 3681 R 740.00 600742 SIFONONDILE JS SCHOOL Combined SIFONONDILE AlA"CALA,5460 NGCOBOI 2 2021 R 740.00 600743 SIFONONDILE SS SCHOOL Secondary SIFONONDILE AlA,CALA,,5455 NGCOBOI 2 771 R 740.00 Combined ~ NGCOBOI 2 2691 R 740.00 600745 SIGWELA JS SCHOOL MANZIMAHLE STORE,NDUM-NDUM LOC. -

2014-2015 Chdm Final Idp Review

Chris Hani District Municipality 2014-2015 IDP Review Final May Council adopted 2014-2015 CHDM FINAL IDP REVIEW The Executive Mayor Chris Hani District Municipality 15 Bells Road Queenstown 5319 www.chrishanidm.gov.za Tel: 045 808 4600 Fax: 045 838 1556 1 Chris Hani District Municipality 2014-2015 IDP Review Final May Council adopted THE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background to this Document The CHDM Council has adopted a 5 year IDP which is for 2012-2017, by the 30th May 2012. By law IDP has to be reviewd annually to accommodate changes as the world changes, meaning by 2014- 2015 there should be a 2nd IDP Review which must not be in contrast with its original 5 year IDP hence this document which is the actual 1st IDP review of the 5 year Plan. It is submitted and prepared in fulfilment of the Municipality’s legal obligation in terms of Section 32 of the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000. Previous Comments from the MEC of Local Government has been taken into consideration and inputted. In addition to the legal requirement for every Municipality to compile an Integrated Development Plan, the Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000 also requires that: . the IDP be implemented; . the Municipality monitors and evaluates its performance with regards to the IDP’s implementation; . the IDP be reviewed annually to effect improvements. Section 25 of the Municipal Systems Act deals with the adoption of the IDP and states that: “Each municipal council must adopt a single, inclusive and strategic plan for the development of the municipality which