How to Characterise the Discourse of the Far-Right in Digital Media? Interdisciplinary Approach to Preventing Terrorism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN SEARCH of COHERENCE Why the EU and Member States Hardly Fostered Resilience in Mali

Working Paper No. 9 April 2021 IN SEARCH OF COHERENCE Why the EU and Member States Hardly Fostered Resilience in Mali Léonard Colomba-Petteng This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 769886 The EU-LISTCO Working Papers are peer-reviewed research papers published based on research from the EU Horizon 2020 funded project no. 769886 entitled Europe’s External Action and the Dual Challenges of Limited Statehood and Contested Orders which runs from March 2018 to February 2021. EU-LISTCO investigates the challenges posed to European foreign policy by identifying risks connected to areas of limited statehood and contested orders. Through the analysis of the EU Global Strategy and Europe’s foreign policy instruments, the project assesses how the preparedness of the EU and its member states can be strengthened to better anticipate, prevent and respond to threats of governance breakdown and to foster resilience in Europe’s neighbourhoods. Continuous knowledge exchange between researchers and foreign policy practitioners is the cornerstone of EU-LISTCO. Since the project's inception, a consortium of fourteen leading universities and think tanks have been working together to develop policy recommendations for the EU’s external action toolbox, in close coordination with European decision-makers. FOR MORE INFORMATION: EU-LISTCO WORKING PAPERS SERIES: EU-LISTCO PROJECT: Saime Ozcurumez, Editor Elyssa Shea Senem Yıldırım, Assistant Editor Freie Universität Berlin -

Different Shades of Black. the Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament

Different Shades of Black. The Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament Ellen Rivera and Masha P. Davis IERES Occasional Papers, May 2019 Transnational History of the Far Right Series Cover Photo: Protesters of right-wing and far-right Flemish associations take part in a protest against Marra-kesh Migration Pact in Brussels, Belgium on Dec. 16, 2018. Editorial credit: Alexandros Michailidis / Shutter-stock.com @IERES2019 Different Shades of Black. The Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament Ellen Rivera and Masha P. Davis IERES Occasional Papers, no. 2, May 15, 2019 Transnational History of the Far Right Series Transnational History of the Far Right Series A Collective Research Project led by Marlene Laruelle At a time when global political dynamics seem to be moving in favor of illiberal regimes around the world, this re- search project seeks to fill in some of the blank pages in the contemporary history of the far right, with a particular focus on the transnational dimensions of far-right movements in the broader Europe/Eurasia region. Of all European elections, the one scheduled for May 23-26, 2019, which will decide the composition of the 9th European Parliament, may be the most unpredictable, as well as the most important, in the history of the European Union. Far-right forces may gain unprecedented ground, with polls suggesting that they will win up to one-fifth of the 705 seats that will make up the European parliament after Brexit.1 The outcome of the election will have a profound impact not only on the political environment in Europe, but also on the trans- atlantic and Euro-Russian relationships. -

Proceedings of TRA2020, the 8Th Transport Research Arena Rethinking Transport – Towards Clean and Inclusive Mobility

Traficom Research Reports 7/2020 Bu Traficom Research Reports 7/2020 Proceedings of TRA2020, the 8th Transport Research Arena Rethinking transport – towards clean and inclusive mobility Toni Lusikka, (ed.) Hosted and organised by Co-organised by Together with Traficom Research Reports 7/2020 Date of publication 28/5/2020 Title of publication Proceedings of TRA2020, the 8th Transport Research Arena: Rethinking transport – towards clean and inclusive mobility Author(s) Lusikka Toni (ed.) Commissioned by, date Finnish Transport and Communications Agency Traficom Publication series and number ISSN (online) 2669-8781 Traficom Research Reports 7/2020 ISBN (online) 978-952-311-484-5 Keywords TRA2020, Transport Research Arena, conference Abstract This publication presents the proceedings of TRA2020, the 8th Transport Research Arena, which was planned to be held on 27-30 April 2020 in Helsinki. The physical conference event was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. All work presented in this Book of Abstracts was peer-reviewed and accepted for the conference. Authors were encouraged to publish their full paper in a repository of their choice with a mention of TRA2020. Authors were invited to provide a link to the full paper to be included in this Book of Abstracts. If the link is not available, please contact the corresponding author to request the full paper. Selection of TRA2020 papers were published in Special Issues of following journals: European Transport Research Review (Vol. 11-12) and Utilities Policy (Vol. 62 & 64). Papers with a TRA VISIONS 2020 senior researcher winner as an author are marked with large yellow stars. Smaller stars stand for papers with an author shortlisted in the TRA VISIONS 2020 competition. -

Governing Globalization

Volume 02 Governing 02 March 2021 Globalization Revue Européenne du Droit GROUPE Scientific Director D’ÉTUDES Mireille Delmas-Marty GÉOPOLITIQUES Revue Européenne du Droit ISSN 2740-8701 Legal Journal edited by the Groupe d’études géopolitiques 45 rue d’Ulm 75005 Paris https://legrandcontinent.eu/ [email protected] Chairman of the Scientific Committee Guy Canivet Scientific Committee Alberto Alemanno, Luis Arroyo Zapatero, Emmanuel Breen, Laurent Cohen-Tanugi, Mireille Delmas-Marty, Pavlos Eleftheriadis, Jean- Gabriel Flandrois, Antoine Gaudemet, Aurélien Hamelle, Noëlle Lenoir, Emmanuelle Mignon, Astrid Mignon Colombet, Alain Pietrancosta, Pierre-Louis Périn, Sébastien Pimont, Pierre Servan-Schreiber, Jorge E. Viñuales. Editors-in-chief Hugo Pascal and Vasile Rotaru Editorial Managers Gilles Gressani and Mathéo Malik Editorial Comittee Lorraine De Groote and Gérald Giaoui (dir.), Dano Brossmann, Jean Cattan, Pierre-Benoit Drancourt, David Djaïz, Sara Gwiadza, Joachim- Nicolas Herrera, Francesco Pastro and Armelle Royer. To cite an article from this Journal: [Name of the author], [Title], Revue européenne du droit, Paris: Groupe d’études géopolitiques, March, 2021, Issue n°2 absence of a comprehensive shared ideology underpin- ning the multiple, disparate and fragmented normative spaces, our societies are still seeking an appropriate le- Mireille Delmas-Marty • Professor Emeritus at gal narrative, able to both reflect and tame them, while Collège de France, Member of the Institut de France avoiding the twin pitfalls of the “great collapse” and of Hugo Pascal • PhD candidate, Panthéon-Assas the “great enslavement”. University Vasile Rotaru • Phd candidate (DPhil), Oxford Indeed, globalization is far from being limited to in- University ternational trade, and calls therefore for new rules of co- REVUE EUROPÉENNE DU DROIT REVUE EUROPÉENNE existence between heterogeneous political communities, without any hope that relevant normative guidelines (the “North Pole”) could arise out of the traditional “hearths” of shared values. -

Path? : Right-Wing Extremism and Right-Wing

Nora Langenbacher, Britta Schellenberg (ed.) IS EUROPE ON THE “RIGHT” PATH? Right-wing extremism and right-wing populism in Europe FES GEGEN RECHTS EXTREMISMUS Forum Berlin Nora Langenbacher, Britta Schellenberg (ed.) IS EUROPE ON THE “RIGHT” PATH? Right-wing extremism and right-wing populism in Europe ISBN 978-3-86872-617-6 Published by Nora Langenbacher and Britta Schellenberg on behalf of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Forum Berlin Project “Combating right-wing extremism“ Hiroshimastr. 17 10785 Berlin Edited by (German and English) Nora Langenbacher Britta Schellenberg Edited by (English) Karen Margolis Translated by (German --> English) Karen Margolis Julia Maté Translated by (English --> German) Harald Franzen Markus Seibel Julia Maté Translated by (Italian --> German) Peter Schlaffer Proofread by (English) Jennifer Snodgrass Proofread by (German) Barbara Hoffmann Designed by Pellens Kommunikationsdesign GmbH Printed by bub Bonner Universitäts-Buchdruckerei Copyright © 2011 by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Contents Preface ........................................................................................................7 RIGHT-WING EXTREMISM AND POPULISMUS IN EUROPE Nora Langenbacher & Britta Schellenberg Introduction: An anthology about the manifestations and development of the radical right in Europe ..................................11 Martin Schulz, MEP ................................................................................27 Combating right-wing extremism as a task for European policy making Michael Minkenberg ...............................................................................37 -

Art Et Perspectives Révolutionnaires Actuelles Gilles Suzanne

Art et perspectives révolutionnaires actuelles Gilles Suzanne To cite this version: Gilles Suzanne. Art et perspectives révolutionnaires actuelles. Incertains regards. Cahiers dra- maturgiques., PUP (Presses universitaires de Provence), 2019, pp.89-96. hal-02747385 HAL Id: hal-02747385 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02747385 Submitted on 3 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Art et perspectives révolutionnaires actuelles Gilles Suzanne Maître de conférences en esthétique et sciences des arts, Aix-Marseille Université, LESA (EA 3274), Aix-en-Provence, France Au printemps 1789, la rédaction des cahiers de doléances fut constitutive d’une culture politique qui se révéla irrépressible dans les mois qui suivirent. 230 années plus tard, mois pour mois, une séance du Grand débat à propos de la culture se déroulait aux Beaux-arts de Paris. Ce 05 mars 2019, d’aucuns l’espéraient comme le reflet de la perspective révolutionnaire dans laquelle les arts s’engagèrent, dans ces mêmes locaux, au printemps 1968. Des 3 769 contributions au Grand débat de la culture 1 se dégage finalement un horizon obscurci par les topiques éculées du discours sur la fracture sociale qui lézarde la République des arts et de la culture. -

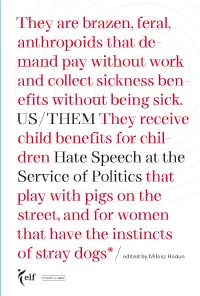

Here: on Hate Speech

They are brazen, feral, anthropoids that de- mand pay without work and collect sickness ben- efits without being sick. US / THEM They receive child benefits for chil- dren Hate Speech at the Service of Politics that play with pigs on the street, and for women that have the instincts of stray dogs * / edited by Miłosz Hodun LGBT migrants Roma Muslims Jews refugees national minorities asylum seekers ethnic minorities foreign workers black communities feminists NGOs women Africans church human rights activists journalists leftists liberals linguistic minorities politicians religious communities Travelers US / THEM European Liberal Forum Projekt: Polska US / THEM Hate Speech at the Service of Politics edited by Miłosz Hodun 132 Travelers 72 Africans migrants asylum seekers religious communities women 176 Muslims migrants 30 Map of foreign workers migrants Jews 162 Hatred refugees frontier workers LGBT 108 refugees pro-refugee activists 96 Jews Muslims migrants 140 Muslims 194 LGBT black communities Roma 238 Muslims Roma LGBT feminists 88 national minorities women 78 Russian speakers migrants 246 liberals migrants 8 Us & Them black communities 148 feminists ethnic Russians 20 Austria ethnic Latvians 30 Belgium LGBT 38 Bulgaria 156 46 Croatia LGBT leftists 54 Cyprus Jews 64 Czech Republic 72 Denmark 186 78 Estonia LGBT 88 Finland Muslims Jews 96 France 64 108 Germany migrants 118 Greece Roma 218 Muslims 126 Hungary 20 Roma 132 Ireland refugees LGBT migrants asylum seekers 126 140 Italy migrants refugees 148 Latvia human rights refugees 156 Lithuania 230 activists ethnic 204 NGOs 162 Luxembourg minorities Roma journalists LGBT 168 Malta Hungarian minority 46 176 The Netherlands Serbs 186 Poland Roma LGBT 194 Portugal 38 204 Romania Roma LGBT 218 Slovakia NGOs 230 Slovenia 238 Spain 118 246 Sweden politicians church LGBT 168 54 migrants Turkish Cypriots LGBT prounification activists Jews asylum seekers Europe Us & Them Miłosz Hodun We are now handing over to you another publication of the Euro- PhD. -

AFTER the STORM Organized Crime Across the Sahel-Sahara Following Upheaval in Libya and Mali

AFTER THE STORM Organized crime across the Sahel-Sahara following upheaval in Libya and Mali MARK MICALLEF │ RAOUF FARRAH │ ALEXANDRE BISH │ VICTOR TANNER AFTER THE STORM Organized crime across the Sahel-Sahara following upheaval in Libya and Mali W Mark Micallef │ Raouf Farrah Alexandre Bish │ Victor Tanner ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Research for this report was directed by Mark Micallef and Raouf Farrah, who also authored the report along with Alexandre Bish and Victor Tanner. Editing was done by Mark Ronan. Graphics and layout were prepared by Pete Bosman and Claudio Landi. Both the monitoring and the fieldwork supporting this document would not have been possible without a group of collaborators across the vast territory that this report covers. These include Jessica Gerken, who assisted with different stages of the project, Giacomo Zandonini, Quscondy Abdulshafi and Abdallah Ould Mrabih. There is also a long list of collaborators who cannot be named for their safety, but to whom we would like to offer the most profound thanks. The research for this report was carried out in collaboration with Migrant Report and made possible with funding provided by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Mark Micallef is a researcher specialized in smuggling and trafficking networks in Libya and the Sahel and an investigative journalist by background. He is a Senior Fellow at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime, where he leads the organization’s research and monitoring on organized crime based on ground networks established in Libya, Niger, Chad and Mali. Raouf Farrah is a Senior Analyst at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. -

Revolutionizing Romania from the Right

Ch F-X ang PD e w w m w Click to buy NOW! o . .c tr e ac ar ker-softw REVOLUTIONIZING ROMANIA FROM THE RIGHT: THE REGENERATIVE PROJECT OF THE ROMANIAN LEGIONARY MOVEMENT AND ITS FAILURE (1927 - 1937) Valentin Adrian Săndulescu A DISSERTATION in History Presented to the Faculties of the Central European University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Budapest, Hungary 2010 CEU eTD Collection Supervisor of Dissertation Professor ROUMEN DASKALOV ______________________ Ch F-X ang PD e w w m w Click to buy NOW! o . .c tr e ac ar ker-softw Copyright in the text of this dissertation rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection I hereby declare that this dissertation contains no materials accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions and no materials previously written and/or published by another person unless otherwise noted. ii Ch F-X ang PD e w w m w Click to buy NOW! o . .c tr e ac ar ker-softw ABSTRACT Rewriting and rethinking history in every generation as a way to mediate, like a translator, between past and present represents the function of a historian, as Peter Burke aptly stated. -

Different Shades of Black. the Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament

Different Shades of Black. The Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament Ellen Rivera and Masha P. Davis IERES Occasional Papers, May 2019 Transnational History of the Far Right Series Different Shades of Black. The Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament Ellen Rivera and Masha P. Davis IERES Occasional Papers, no. 2, May 15, 2019 Transnational History of the Far Right Series Transnational History of the Far Right Series A Collective Research Project led by Marlene Laruelle At a time when global political dynamics seem to be moving in favor of illiberal regimes around the world, this re- search project seeks to fill in some of the blank pages in the contemporary history of the far right, with a particular focus on the transnational dimensions of far-right movements in the broader Europe/Eurasia region. Cover Photo: Protesters of right-wing and far-right Flemish associations take part in a protest against Marra- kesh Migration Pact in Brussels, Belgium on Dec. 16, 2018. Editorial credit: Alexandros Michailidis / Shutter- stock.com @IERES2019 Of all European elections, the one scheduled for May 23-26, 2019, which will decide the composition of the 9th European Parliament, may be the most unpredictable, as well as the most important, in the history of the European Union. Far-right forces may gain unprecedented ground, with polls suggesting that they will win up to one-fifth of the 705 seats that will make up the European parliament after Brexit.1 The outcome of the election will have a profound impact not only on the political environment in Europe, but also on the trans- atlantic and Euro-Russian relationships. -

Curso De Derecho Político

Curso de DERECHO POLITICO Segunda Edición prólogo: Federico PINEDO Augusto Diego LAFFERRIERE Contenido de los elementos esenciales para la materia dictada en la: Universidad Católica Argentina Depto. De Derecho – Facultad Teresa de Àvila Paraná, Prov. Entre Ríos - Argentina CURSO DE DERECHO POLÍTICO Elementos básicos para la introducción al estudio del Derecho Político conforme al programa vigente de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Católica Argentina, Sede Paraná (Entre Ríos). Autor: Augusto Diego LAFFERRIERE 2020 Augusto Diego LAFFERRIERE Profesor de Derecho Político (Universidad Católica Argentina) Miembro de la Asociación Argentina de Derecho Constitucional Máster en Relaciones Internacionales (FLACSO Argentina). Ex asesor jurídico de: H. Cámara Diputados de la Nación; Convención Constituyente Prov. Entre Ríos (2008); y H. Senado de la Prov. Entre Ríos. CURSO DE DERECHO POLÍTICO Elementos básicos para la introducción al estudio del Derecho Político conforme al programa vigente de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Católica Argentina, Sede Paraná (Entre Ríos). 2020 Lafferriere, Augusto Diego Curso de derecho político : elementos básicos para la introducción al estudio del Derecho Político conforme al programa vigente de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad Católica Argentina, Sede Paraná, Entre Ríos / Augusto Diego Lafferriere. - 2a ed. - Nogoyá : Augusto Diego Lafferriere, 2020. 430 p. ; 23 x 16 cm. ISBN 978-987-42-0168-3978-987-86-4400-4 1. Derecho Constitucional . I. Título. CDD 342.00711 Fecha de catalogación: -

Nationalism in Times of Pandemic: How the Radical and Extreme-Right Framed the COVID-19 Crisis in France | Istanbul Bilgi University PRIME Youth Website

4/28/2020 Nationalism in times of pandemic: How the radical and extreme-right framed the COVID-19 crisis in France | Istanbul Bilgi University PRIME Youth Website Nationalism in times of pandemic: How the radical and extreme-right framed the COVID- 19 crisis in France Author: Max-Valentin Robert, ERC PRIME Youth Project Researcher, Published: April 27, 2020, 5:21 p.m. European Institute, İstanbul Bilgi University; and Ph.D. Candidate in Political Edited: April 27, 2020, 5:25 p.m. Science at Sciences Po Grenoble, UMR Pacte, France. On March 17, 2020, the French authorities implemented a wide-ranging See all BLOG lockdown in an effort to contain the spread of Coronavirus. On the previous day, Emmanuel Macron had declared in a televised speech that France was “at war”, and that “many certainties and long-held beliefs will be swept away Share and questioned. Many things that we thought impossible are happening”.[1] The French media sometimes portrayed this global pandemic as a “globalisation disease”, and a challenge to the neoliberal order. Across Europe, radical right parties, and extreme-right organisations view this challenge as a validation of their own ideological leanings. Does this trend apply to France? The movements that I will deal with are characterised by deep ideological divergences, but are also distinct in their degrees of institutionalisation: some of them are political parties which try to gain power by the ballot boxes, whereas others are media or small groups that are not enshrined in the electoral cycle. According to Cas Mudde,[2] extreme right ideologies “believe that inequalities between people are natural and positive and […] reject the essence of democracy” (popular sovereignty).