Tom's Wild Year: the Story of Swordfishtrombones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Réédition Des Sept Premiers Albums De Tom

PÉRIODES À ses débuts, l’auteur- compositeur proposait déjà une musique aussi intemporelle que parfois anachronique, mais toujours novatrice. Tom WaiTs L’invitation au bLues La réédition des sept premiers albums de Tom Waits nous ramène vers la période jazz-blues de ce magicien des sons, farouchement atypique, mû par la seule obsession de rester toujours au plus près de lui-même. Pour mieux nous enchanter. Par Alain Gouvrion. Photographie de Jess Dylan To m Wa i Ts n le croyait à jamais brouillé avec son passé, cette image de bluesman Jones, et son pote le chanteur et composi - HORS DU TEMPS titubant sous un réverbère au son moelleux d’une contrebasse de jazz et d’un sax teur Chuck E. Weiss, futur héros de “Chuck “À 20 ans, je réfutais la culture hippie... Et c’est ténor. Celle de The Heart of Saturday Night et autres galettes gravées au mitan E’s in Love”, le premier succès de Jones. Tom toujours le cas...” des années 70, lorsque Tom Waits surgit de nulle part pour nous ensorceler de et Chuck forment un étrange binôme qui ses ténébreuses romances, sublimement anachroniques : “Tom Traubert’s Blues”, n’est pas sans rappeler celui de Jack Kerouac “Invitation to the Blues”, “Waltzing Matilda” ou l’inusable “Blue Valentine”. Lancé et de Neal Cassady, le chien fou de On the Odans des aventures sonores beaucoup plus audacieuses depuis trente-cinq ans, Road. Des années plus tôt, Waits a été litté- (Swordfishtrombones, 1983), Waits semblait n’éprouver aucune nostalgie – contrairement à ralement foudroyé par Kerouac et les nombre de ses fans – pour le (bon vieux) temps où il passa de l’anonymat des clubs de écrivains beat, qu’il a découverts via son Los Angeles au statut d’artiste culte vénéré par nombre de musiciens, tels que Bruce idole Bob Dylan. -

November 15, 1974

-53=** e ^Br&eze VoLLI Madison College.Harrisonburg.Va.,Friday ^November 15,1974 No. 20 Debaters Expand; 2 Divisions Now Cross-Section of Students By JENNIFER GOINS opportunity to meet Inter- Intercollegiate debate has esting people." evolved from a bawdy battle Madison's coaches, John of wits, which too after re- Morello and Eaiie Malman, sulted In a battle of fists, both former debaters, state Into a highly structured game their motives for debating In of verbal ping-pong. Twen- terms of a three-fold goal. tieth century debate Is less They see debate first as an emotional, more stylish and educational opportunity that success relies on careful ar- teaches students how to re- gumentation rather than brute search arguements, present force. them logically, and defend Madison's five-year old them heartily. Secondly, de- debate team has grown from a bate helps students achieve a fledgling group of four stud- greater form of current ents with one coach, to a awareness. Finally, debate twelve member squad with has social value, it offers the two coaches. Madison's team student a chance to travel has two divisions, with nine meet Interesting people, work members In varsity and three with people, and exchange new members In the novice divi- Idee*. Tournament Upcoming sion. To sophomore Roger Wells, debate Is a game that satis- DEBATORS PREPARE FOR Madison's fifth son Halls. Although debating requires up to Traditionally, Intercolle- fies his InteUectual curiosity and largest annual tournament, which Is be- fifteen hours of work a week, tne rewards giate debate Is a year long and takes his mind off bis ing held this weekend In Jackson and Harri- a debater gains are tremendous. -

Bourdieu and the Music Field

Bourdieu and the Music Field Professor Michael Grenfell This work as an example of the: Problem of Aesthetics A Reflective and Relational Methodology ‘to construct systems of intelligible relations capable of making sense of sentient data’. Rules of Art: p.xvi A reflexive understanding of the expressive impulse in trans-historical fields and the necessity of human creativity immanent in them. (ibid). A Bourdieusian Methodology for the Sub-Field of Musical Production • The process is always iterative … so this paper presents a ‘work in progress’ … • The presentation represents the state of play in a third cycle through data collection and analysis …so findings are contingent and diagrams used are the current working diagrams! • The process begins with the most prominent agents in the field since these are the ones with the most capital and the best configuration. A Bourdieusian Approach to the Music Field ……..involves……… Structure Structuring and Structured Structures Externalisation of Internality and the Internalisation of Externality => ‘A science of dialectical relations between objective structures…and the subjective dispositions within which these structures are actualised and which tend to reproduce them’. Bourdieu’s Thinking Tools “Habitus and Field designate bundles of relations. A field consists of a set of objective, historical relations between positions anchored in certain forms of power (or capital); habitus consists of a set of historical relations ‘deposited’ within individual bodies in the forms of mental and corporeal -

Residential Property Owners As Of: 2/10/2021 Two and Three Family

Residential Property Owners as of: 2/10/2021 Two and Three Family Sect Taxkey Property Address Owner Name Secondary Owner Owner Address Owner CityState,Zip Property Use 32 415-0006-000 10006 W Bungalow Pkwy Aaron S. Jacobson Glenn Barber 671 S 100 St West Allis, WI 53214 940 Residential Duplex 32 415-0013-000 10202 W Bungalow Pkwy Ronald C. Shikora Doris J. Shikora 4085 Brook Ln Brookfield, WI 53005 940 Residential Duplex 32 416-0019-000 651 S 93 St Reddie Living Trust 651 S 93 St West Allis, WI 53214 940 Residential Duplex 32 416-0023-001 681 S 93 St Corry S. Eifert Sandra S. Eifert 2745 S 132 St New Berlin, WI 53151 940 Residential Duplex 32 416-9981-001 9732 W Schlinger Ave Shirley Kewan 9732 W Schlinger Ave West Allis, WI 53214 940 Residential Duplex 33 417-0009-000 9116 W Conrad Ln Jeffrey J. Raab N3430 County Rd K Jefferson, WI 53549 940 Residential Duplex 35 438-0001-000 705 S 57 St Gary J. Karabelas Carol A. Karabelas 6009 W Mitchell St West Allis, WI 53214 940 Residential Duplex 35 438-0009-000 804 S 58 St Santiago Rodriguez Iraviregen Rodriguez 804 S 58 St West Allis, WI 53214 940 Residential Duplex 35 438-0024-000 810 S 57 St Christopher J. Lake Rebecca T. Long-Lake PO Box 204 Big Bend, WI 53103 940 Residential Duplex 35 438-0029-004 702 S 57 St Jeffrey T. Anderson 125 N 70 St Milwaukee, WI 53213 940 Residential Duplex 35 438-0038-000 1000 S 58 St Gary L. -

James S. Jaffe Rare Books Llc

JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS LLC OCCASIONAL LIST: DECEMBER 2019 P. O. Box 930 Deep River, CT 06417 Tel: 212-988-8042 Email: [email protected] Website: www.jamesjaffe.com Member Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers All items are offered subject to prior sale. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. Digital images are available upon request. 1. AGEE, James. The Morning Watch. 8vo, original printed wrappers. Roma: Botteghe Oscure VI, 1950. First (separate) edition of Agee’s autobiographical first novel, printed for private circulation in its entirety. One of an unrecorded number of offprints from Marguerite Caetani’s distinguished literary journal Botteghe Oscure. Presentation copy, inscribed on the front free endpaper: “to Bob Edwards / with warm good wishes / Jim Agee”. The novel was not published until 1951 when Houghton Mifflin brought it out in the United States. A story of adolescent crisis, based on Agee’s experience at the small Episcopal preparatory school in the mountains of Tennessee called St. Andrew’s, one of whose teachers, Father Flye, became Agee’s life-long friend. Wrappers dust-soiled, small area of discoloration on front free-endpaper, otherwise a very good copy, without the glassine dust jacket. Books inscribed by Agee are rare. $2,500.00 2. [ART] BUTLER, Eugenia, et al. The Book of Lies Project. Volumes I, II & III. Quartos, three original portfolios of 81 works of art, (created out of incised & collaged lead, oil paint on vellum, original pencil drawings, a photograph on platinum paper, polaroid photographs, cyanotypes, ashes of love letters, hand- embroidery, and holograph and mechanically reproduced images and texts), with interleaved translucent sheets noting the artist, loose as issued, inserted in a paper chemise and cardboard folder, or in an individual folder and laid into a clamshell box, accompanied by a spiral bound commentary volume in original printed wrappers printed by Carolee Campbell of the Ninja Press. -

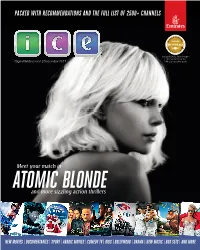

Packed with Recommendations and the Full List of 2500+ Channels

PACKED WITH RECOMMENDATIONS AND THE FULL LIST OF 2500+ CHANNELS Voted World’s Best Infl ight Entertainment for the Digital Widescreen | December 2017 13th consecutive year! Meet your match in ATOMIC BLONDE and more sizzling action thrillers NEW MOVIES | DOCUMENTARIES | SPORT | ARABIC MOVIES | COMEDY TV | KIDS | BOLLYWOOD | DRAMA | NEW MUSIC | BOX SETS | AND MORE OBCOFCDec17EX2.indd 51 09/11/2017 15:13 EMIRATES ICE_EX2_DIGITAL_WIDESCREEN_62_DECEMBER17 051_FRONT COVER_V1 200X250 44 An extraordinary ENTERTAINMENT experience... Wherever you’re going, whatever your mood, you’ll find over 2500 channels of the world’s best inflight entertainment to explore on today’s flight. THE LATEST Information… Communication… Entertainment… Track the progress of your Stay connected with in-seat* phone, Experience Emirates’ award- MOVIES flight, keep up with news SMS and email, plus Wi-Fi and mobile winning selection of movies, you can’t miss movies and other useful features. roaming on select flights. TV, music and games. from page 16 527 ...AT YOUR FINGERTIPS STAY CONNECTED 4 Connect to the 1500 OnAir Wi-Fi network on all A380s and most Boeing 777s 1 Choose a channel Go straight to your chosen programme by typing the channel WATCH LIVE TV 2 3 number into your handset, or use the onscreen channel entry pad Live news and sport channels are available on 1 3 Swipe left and Search for Move around most fl ights. Find out right like a tablet. movies, TV using the games more on page 9. Tap the arrows shows, music controller pad onscreen to and system on your handset scroll features and select using the green game 2 4 Create and Tap Settings to button 4 access your own adjust volume playlist using and brightness Favourites Home Again Many movies are 113 available in up to eight languages. -

Tom Waits Used Songs 1973-1980 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Tom Waits Used Songs 1973-1980 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Used Songs 1973-1980 Country: Japan Released: 2011 MP3 version RAR size: 1764 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1892 mb WMA version RAR size: 1332 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 372 Other Formats: ASF AAC APE ADX VOC MP3 WMA Tracklist Hide Credits Heartattack And Vine 1 Baritone Saxophone, Tenor Saxophone – Plas JohnsonBass – Larry TaylorDrums – John 4:45 ThomassieElectric Guitar – Tom WaitsEngineer [Assistant] – Geoff Howe Eggs And Sausage (In A Cadillac With Susan Michelson) Bass – Jim HughartDrums – Bill GoodwinElectric Piano – Mike MelvoinEngineer [Assistant] 2 4:23 – Kelly Kotera, Norm Dlugatch, Rick Smith , Ron Marks , Steve Smith Piano – Tom WaitsTenor Saxophone – Pete Christlieb A Sight For Sore Eyes 3 4:41 Bass – Jim HughartEngineer [Assistant] – Geoff HowePiano – Tom Waits Whistlin' Past The Graveyard Bass – Scott Edwards Drums – Earl PalmerElectric Guitar – Alvin "Shine" Robinson*, Tom 4 3:16 WaitsEngineer [Assistant] – Geoff Howe, Ralph Osborne*Piano – Harold BattisteTenor Saxophone – Herbert Hardesty* Burma Shave 5 Bass – Jim HughartEngineer [Assistant] – Geoff HoweTrumpet – Jack SheldonVocals, Piano 6:34 – Tom Waits Step Right Up 6 Bass – Jim HughartDrums – Shelly ManneEngineer [Assistant] – Bill Broms, Geoff 5:41 HoweTenor Saxophone – Lew Tabackin Ol' '55 7 Bass – Bill PlummerDrums, Vocals – John SeiterEngineer – Richie Moore*Guitar – Peter 3:58 KlimesPiano – Tom Waits I Never Talk To Strangers 8 Arranged By, Conductor – Bob AlcivarBass – Jim HughartEngineer -

Woyzeck Bursts Onto the Ensemble Theatre Company Stage

MEDIA RELEASE CONTACT: Josh Gren [email protected] or 805.965.5400 x103 ELECTRIFYING TOM WAITS MUSICAL WOYZECK BURSTS ONTO THE ENSEMBLE THEATRE COMPANY STAGE March 25, 2015 – Santa Barbara, CA — The influential 19th Century play about a soldier fighting to retain his humanity has been transformed into a tender and carnivalesque musical by the legendary vocalist, Tom Waits. “If there’s one thing you can say about mankind,” the show begins, “there’s nothing kind about man.” The haunting opening phrase is the heart of the thrilling, bold, and contemporary English adaptation of Woyzeck – the classic German play, being presented at Ensemble Theatre Company this April. Inspired by the true story of a German soldier who was driven mad by army medical experiments and infidelity, Georg Büchner’s dynamic and influential 1837 poetic play was left unfinished after the untimely death of its author. In 2000, Waits and his wife and collaborator, Kathleen Brennan, resurrected the piece, wrote music for an avant-garde production in Denmark, and the resulting work became a Woyzeck musical and an album entitled “Blood Money.” “[The music] is flesh and bone, earthbound,” says Waits. “The songs are rooted in reality: jealousy, rage…I like a beautiful song that tells you terrible things. We all like bad news out of a pretty mouth.” Woyzeck runs at the New Vic Theater from April 16 – May 3 and opens Saturday, April 18. Jonathan Fox, who has served as ETC’s Executive Artistic Director since 2006, will direct the ambitious, wild, and long-awaited musical. “It’s one of the most unusual productions we’ve undertaken,” says Fox. -

Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart and the Secret History of Maximalism

Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart and the Secret History of Maximalism Michel Delville is a writer and musician living in Liège, Belgium. He is the author of several books including J.G. Ballard and The American Prose Poem, which won the 1998 SAMLA Studies Book Award. He teaches English and American literatures, as well as comparative literatures, at the University of Liège, where he directs the Interdisciplinary Center for Applied Poetics. He has been playing and composing music since the mid-eighties. His most recently formed rock-jazz band, the Wrong Object, plays the music of Frank Zappa and a few tunes of their own (http://www.wrongobject.be.tf). Andrew Norris is a writer and musician resident in Brussels. He has worked with a number of groups as vocalist and guitarist and has a special weakness for the interface between avant garde poetry and the blues. He teaches English and translation studies in Brussels and is currently writing a book on post-epiphanic style in James Joyce. Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart and the Secret History of Maximalism Michel Delville and Andrew Norris Cambridge published by salt publishing PO Box 937, Great Wilbraham PDO, Cambridge cb1 5jx United Kingdom All rights reserved © Michel Delville and Andrew Norris, 2005 The right of Michel Delville and Andrew Norris to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing. -

Record Dedicated to Serving the Needs of the Music & Record Worldindustry

record Dedicated To Serving The Needs Of The Music & Record worldIndustry May 11, 1969 60c In the opinion of the editors, this week the following records are the WHO IN SINGLE PICKS OF THE WEEK THE WORLD -.A.11111111." LOVE MI TONIGHT TON TOWS Tom Jones, clicking on Young -HoltUnlimited have JerryButlerhas a spicy Bob Dylan sings his pretty stateside TV these days, a new and funky ditty and moodyfollow-up in "I Threw ftAll Away" (Big shouldscoreveryheavily called "Young and Holtful" "Moody Woman" (Gold Sky, ASCAP), which has with"Love Me Tonight" (Dakar - BRC, BMI), which Forever-Parabut, BMI(,pro- caused muchtalkinthe (Duchess, BMI)(Parrot hassomejazzandLatin duced by Gamble -Huff (Mer- "NashvilleSkyline"elpee 40038(. init (Brunswick 755410). cury 72929). (Columbia 4-448261. SLEEPER PICKS OF THE WEEK TELLING ALRIGHT AM JOE COCKER COLOR HIM FATHER THE WINSTONS Joe Cocker sings the nifty The Winstons are new and Roy Clark recalls his youth TheFive Americans geta Traffic ditty that Dave will make quite a name for on the wistful Charles Az- lot funkier and funnier with Mason wrote, "FeelingAl- themselveswith"Color navour - Herbert Kretzmer, "IgnertWoman" (Jetstar, right" (Almo, ASCAP). Denny Him Father"(Holly Bee, "Yesterday,When I Was BMI(, which the five guys Cordell produced (A&M BMI), A DonCarrollPra- Young"(TRO - Dartmouth, wrote (Abnak 137(. 1063). duction (Metromedia117). ASCAP) (Dot 17246). ALBUM PICKS OF THE WEEK ONUTISNINF lUICICCIENS GOLD "Don Kirshner Cuts 'Hair' " RogerWilliams plays "MacKenna's Gold," one of Larry Santos is a newcomer is just what the title says "HappyHeart" andalso the big summer movies, has with a big,huskyvoice I hree Records from 'Hair' withHerbBernsteinsup- getsmuchivorymileage a scorebyQuincy Jones and a good way with tune- plying arrangements and from "Those Were the and singing byJoseFeli- smithing. -

Tom Waits Swordfishtrombones Free

FREE TOM WAITS SWORDFISHTROMBONES PDF David Smay | 144 pages | 15 Feb 2008 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9780826427823 | English | London, United Kingdom Swordfishtrombones - Tom Waits | Songs, Reviews, Credits | AllMusic More Images. Please enable Javascript to take full advantage of our site features. Edit Master Release. JazzRock. Blues RockLoungeTom Waits Swordfishtrombones. Francis Tom Waits Swordfishtrombones Arranged By. Frank Mulvey Art Direction. Michael Solomon 2 Coordinator. Bill Jackson Engineer. Peggy McCreary Engineer. Richard McKernan Engineer. Arlyne Rothberg Management. Bill Gerber Management. Jeff Sanders Mastered By. But considering where he was coming from, Tom Waits Swordfishtrombones is such a wide range of music here- I'd say a perfect balance between what was and what will be. So many different feelings and energy at every turn. Just a brilliant album. This Canadian pressing sounds very good. Reply Notify me Helpful. So alive. Note: only pressing i heard from this album. No crackle at all, recommended. FromThisPosition June 7, Report. MrShocktime May 3, Report. Did anyone else receive either with theirs? The quality is actually spectacular! One of the best vinyl records I own. Reply Notify me 1 Helpful. Add all to Wantlist Remove all from Wantlist. Have: Want: Avg Rating: 4. Listened by hipp-e. First Tom Waits Swordfishtrombones about My Music by chris. Absolutely Classic Albums by Joost Best albums of by dj-maus. Shore Leave. Dave The Butcher. Johnsburg, Illinois. Town With No Cheer. In The Neighborhood. Frank's Wild Years. Down, Down, Down. Soldier's Things. Gin Soaked Boy. Trouble's Braids. Island RecordsIsland Records. Sell This Version. Island Records. Asylum Records. -

Clangxboomxstea ... Vxtomxwaitsxxlxterxduo.Pdf

II © Karl-Kristian Waaktaar-Kahrs 2012 Clang Boom Steam – en musikalsk lesning av Tom Waits’ låter Forsidebilde: © Massimiliano Orpelli (tillatelse til bruk er innhentet) Konsertbilde side 96: © Donna Meier (tillatelse til bruk er innhentet) Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo III IV Forord Denne oppgaven hadde ikke vært mulig uten støtten fra noen flotte mennesker. Først av alt vil jeg takke min veileder, Stan Hawkins, for gode innspill og råd. Jeg vil også takke ham for å svare på alle mine dumme (og mindre dumme) spørsmål til alle døgnets tider. Spesielt i den siste hektiske perioden har han vist stor overbærenhet med meg, og jeg har mottatt hurtige svar selv sene fredagskvelder! Jeg skulle selvfølgelig ha takket Tom Waits personlig, men jeg satser på at han leser dette på sin ranch i «Nowhere, California». Han har levert et materiale som det har vært utrolig morsomt og givende å arbeide med. Videre vil jeg takke samboeren min og mine to stadig større barn. De har latt meg sitte nede i kjellerkontoret mitt helg etter helg, og all arbeidsroen jeg har hatt kan jeg takke dem for. Jeg lover dyrt og hellig å gjengjelde tjenesten. Min mor viste meg for noen år siden at det faktisk var mulig å fullføre en masteroppgave, selv ved siden av en krevende fulltidsjobb og et hektisk familieliv. Det har gitt meg troen på prosjektet, selv om det til tider var slitsomt. Til sist vil jeg takke min far, som gikk bort knappe fire måneder før denne oppgaven ble levert. Han var alltid opptatt av at mine brødre og jeg skulle ha stor frihet til å forfølge våre interesser, og han skal ha mye av æren for at han til slutt endte opp med tre sønner som alle valgte musikk som sin studieretning.