Marx's Furtherwork on Capital After Publishing Volume I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tugan-Baranowsky and Effective Demand

Science & Society, Vol. 71, No. 2, April 2007, 227-242 Tugan-Baranowsky and Effective Demand JOHN MIUOS and DIMITRIS SOTIROPOULOS ABSTRACT: Tugan-Baranowsky criticized underconsuption cri- sis theories on the hasis of Marx's reproduction schemes in Vol. II of Capital. However, he incorporated in his analysis the "ahsolute immiseration thesis," and claimed that "proportional- ity" between production sectors would exclude any possibility of crisis, despite the supposedly continuous fall in mass consump- tion. This approach allows for a Keynesian interpretation of Marx's theory of expanded reproduction of social capital, accord- ing to which a constantly increasing investment demand may always compensate for the lacking demand for consumer goods. In contrast to Keynesian approaches, the ultimate "cause" of an economic crisis is found to be not "lack of demand" but "lack of surplus value," in the sense that the totality of capitalist contra- dictions renders capital unable to exploit labor at the level of exploitation that is required for sustaining profitability rates. HE UKRAINIAN ECONOMIST Professor Mikhail von Tugan- Baranowsky (1865-1919) is mainly known as a critical expo- Tnent of Marx's theory and method, who first formulated a radical critique of underconsumption theories (Milios, 1994; Milios, et at, 2002) and also laid the foundation of what is nowadays known as the Surplus Approach School (Ramos-Martinez, 2000). In this paper we are going to critically discuss the Keynesian interpretation and use of Tugan-Baranowsky's arguments and theoretical contra- dictions, which aims at turning him into an early formulator of the "effective demand principle" and thus an (immature) exponent of modern (Keynesian) underconsumptionism. -

Marx and History: the Russian Road and the Myth of Historical Determinism

Ciências Sociais Unisinos 57(1):78-86, janeiro/abril 2021 Unisinos - doi: 10.4013/csu.2021.57.1.07 Marx and history: the Russian road and the myth of historical determinism Marx e a história: a via russa e o mito do determinismo histórico Guilherme Nunes Pires1 [email protected] Abstract This paper aims to point out the limits of the historical determinism thesis in Marx’s thought by analyzing his writings on the Russian issue and the possibility of a “Russian road” to socialism. The perspective of historical determinism implies that Marx’s thought is supported by a unilinear view of social evolution, i.e. history is understood as a succes- sion of modes of production and their internal relations inexorably leading to a classless society. We argue that in letters and drafts on the Russian issue, Marx opposes to any attempt associate his thought with a deterministic conception of history. It is pointed out that Marx’s contact with the Russian populists in the 1880s provides textual ele- ments allowing to impose limits on the idea of historical determinism and the unilinear perspective in the historical process. Keywords: Marx. Historical Determinism. Unilinearity. Russian Road. Resumo O objetivo do presente artigo é apontar os limites da tese do determinismo histórico no pensamento de Marx, através da análise dos escritos sobre a questão russa e a possibilidade da “via russa” para o socialismo. A perspectiva do determinismo histórico compreende que o pensamento de Marx estaria amparado por uma visão unilinear da evolução social, ou seja, a história seria compreendida por uma sucessão de modos de produção e suas relações internas que inexoravelmente rumaria a uma sociedade sem classes sociais. -

Constant and Variable Capital

1598 constant and variable capital constant and variable capital Macmillan. Palgrave 1 Definition In Das Kapital Marx defined Constant Capital as that part of capital advanced in the means of Licensee: production; he defined Variable Capital as the part of capital advanced in wages (Marx, 1867, Vol. I, ch. 6). These definitions come from his concept of Value: he defined the value of permission. commodities as the amount of labour directly and indirectly necessary to produce commodities without (Vol. I, ch. 1). In other words, the value of commodities is the sum of C and N, where C is the value of the means of production necessary to produce them and N is the amount of labour used distribute that is directly necessary to produce them. The value of the capital advanced in the means of or production is equal to C. copy However, the value of the capital advanced in wages is obviously not equal to N, because it not may is the value of the commodities which labourers can buy with their wages, and has no direct You relationship with the amount of labour which they actually expend. Therefore, while the value of the part of capital that is advanced in the means of production is transferred to the value of the products without quantitative change, the value of the capital advanced in wages undergoes quantitative change in the process of transfer to the value of the products. This is the reason why Marx proposed the definitions of constant capital C and variable capital V. The definition of constant capital and variable capital must not be confused with the definition of fixed capital and liquid capital. -

Education, Financial Markets and Economic Growth

Lucas Papademos: Education, financial markets and economic growth Speech by Mr Lucas Papademos, Vice-President of the European Central Bank, at the 35th Economics Conference on “Human Capital and Economic Growth” organised by the Austrian National Bank, Vienna, 21 May 2007. * * * I. Introduction “Upon the education of the people of this country the fate of this country depends”, British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli observed over 100 years ago with great prescience. Today, his insightful observation about the crucial importance of education and human capital for the welfare of countries and the performance of their economies is widely recognised, especially in all advanced countries with their increasingly knowledge-based economies. In Europe, the Lisbon strategy has placed education high on the policy agenda – together with some key structural reforms in product, labour and capital markets – in order to make Europe a more competitive, knowledge-based and dynamic economy. It is, therefore, highly appropriate and very much appreciated that the Österreichische Nationalbank has devoted its 35th Economics Conference to the topic of “Human capital and economic growth”, and I am delighted to have been invited to address this distinguished audience. Education contributes significantly to economic growth and welfare through various channels and in many ways. [SLIDE 2] In the first part of my presentation, I will review these channels and assess their relative importance on the basis of the available empirical evidence about the quantitative significance of the effects of education on a number of key determining factors of growth. In particular, I will examine the role of education in accounting for differences in economic growth across countries and regions, as well as for the growth performance of different sectors within our economies. -

A Multi Capital Approach to Understanding Participation in Professional Management Education

A multi capital approach to understanding participation in professional management education. Jane Simmons Hope Business School, Liverpool Hope University, Liverpool, England Hope Park Liverpool England L16 9JD Working paper Stream: Vocational Education and Training and Continuing Professional Education and Development Email [email protected] Telephone 44 (0)151 291 3911 This paper presents the outcomes of research which has been framed by a multi capital approach. It reflects, and illuminates the rationale for engagement in continuing professional development and focuses on a case study of employees, and their employers, who are engaged in Chartered Management Institute professional courses at a university in the northwest of England. This phenomenological study used two methods sequentially, quantitative by the use of questionnaires and qualitative by the use of interviews. These were used by the researcher to construct the stories of the respondents. Fifty questionnaires were completed by employees and fifteen interviews were undertaken, out of a total population of eight one. The entire population of twenty four employees completed a questionnaire and six of them were interviewed. In this study the researcher aimed to describe, as accurately as possible, the phenomena, professional management education, lifelong learning and the cultural, economic, human and social capitals of the respondents. It was concerned with the lived experiences of the people involved, or who were involved, with the issue that is being researched. The respondents were encouraged to reflect on their lived experiences, which were explored by way of their stories. The outcomes of the research highlight the changing nature of the workplace in the twenty first century together with the impact of the current adverse economic climate. -

Examining the Main Street Benefits of Our Modern Financial Markets

Examining the Main Street Benefits of our Modern Financial Markets Charles M. Jones and Erik R. Sirri Charles Jones is the Robert W. Lear Professor of Finance and Economics at Columbia Business School, and Erik Sirri is a Professor of Finance at Babson College. This paper was written for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Executive Summary America’s vibrant capital markets are the global gold standard, fueling the financial needs of business from the smallest single-person startup to our largest public companies. They enable the dreams of American families and help make the American economy the envy of the world. In this report, we show how Main Street businesses and workers benefit from our nation’s well-regulated, efficient, transparent, and modern capital markets. We also demonstrate that seemingly small changes such as a financial transactions tax can cause considerable damage far from Wall Street, harming both investors and American businesses and impeding job recovery and growth. Over the past twenty years or so, technology and competition have dramatically reduced the cost of investing. They have made our markets fairer than ever before, giving average investors access to the best possible price when they buy and sell. This liquidity and accessibility benefits companies large and small. Stock prices are higher, enabling more investment and job creation. Mid-cap and small-cap companies have a less costly path to the public markets, and venture capitalists are more likely to provide funding as a result. The United States currently has highly liquid and highly automated capital markets. In the wake of the recent financial crisis, some have questioned whether this increased liquidity and automation in our capital markets benefits average Americans. -

The Non-Taxation of Liquidity

The Non-Taxation of Liquidity By Yair Listokin1 Word Count: 19,489 Abstract: One of the principal determinants of an asset’s return is its liquidity—the ease with which the asset can be bought and sold. Liquid assets yield a lower return than otherwise comparable illiquid assets. This article demonstrates that an income tax alters the trade-off between asset liquidity and yield because high yields from illiquid assets are taxed while imputed transaction services income from liquidity is untaxed. As a result, asset liquidity is overproduced and the price of liquidity in terms of yield is higher than it would be in the absence of an income tax. These distortions foster an excessively large financial sector, which exists in large part to create (tax favored) liquidity. The tax wedge between liquidity and yield also creates clientele effects, where low rate taxpayers, such as non-profit institutions, hold illiquid assets regardless of their liquidity needs. The liquidity/yield tax distortion also offers a new perspective on fundamental questions in federal income tax, such as the desirability of the realization requirement, corporate taxation, consumption taxes, wealth taxes, and transaction taxes. 1 Associate Professor of Law, Yale Law School. I thank Alan Auerbach, Ian Ayres, Dhammika Dharmapala, Henry Hansmann, Daniel Markovits, Michael Graetz and participants at Columbia Law School’s Summer Tax Workshop for very helpful comments and discussions. All errors are my own. 1 Table of Contents The Non-Taxation of Liquidity ........................................................................................................ 1 I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 4 II. Asset Prices and Liquidity .................................................................................................... 7 A. The Theoretical Basis for a Tradeoff Between Returns and Liquidity ............................ -

Lenin As a Development Economist: a Study in Application of Marx's Theory

Russian Journal of Economics 7 (2021) 34–49 DOI 10.32609/j.ruje.7.57963 Publication date: 31 March 2021 www.rujec.org Lenin as a development economist: A study in application of Marx’s theory in Russia Denis V. Melnik* HSE University, Moscow, Russia Abstract The paper provides an interpretation of Lenin’s earliest contributions (made in 1893–1899) to the study of economic development. In the 1890s, Lenin joined young Marxist intellectu- als in their fight against the Narodnik economists, who represented the approach prevalent among the Russian radical intelligentsia in the 1870s–1880s. That was the fight over the right to control the Marxist narrative in Russia. Lenin elaborated his theoretical interpretation of Marxism as applied to the contentious issues of Russia’s economic development. The paper outlines the context of Lenin’s activity in the 1890s. It suggests that the main theoretical challenge to “orthodox Marxist” intellectuals in applying Marx’s theory to Russia stemmed not from their designated opponents, but from Marx himself, who presented two divergent scenarios — the dynamic and the breakdown — for capitalist development. Lenin provided an analytical substantiation for the dynamic one but eventually allowed for consideration of structural heterogeneity in the development process. This resulted in the notion of uneven- ness, on which he would rely upon later, in his studies of imperialism. The paper also briefly considers the place of Lenin’s early development studies in his legacy. Keywords: Lenin, Marxism, Marxism in Russia, theories of economic development, Marxist theory of accumulation. JEL classification: B14, B24, B31. 1. Introduction The amount of literature dedicated to Lenin is vast. -

RESEARCH in POLITICAL ECONOMY Series Editor: Paul Zarembka State University of New York at Buffalo, USA

CLASS HISTORY AND CLASS PRACTICES IN THE PERIPHERY OF CAPITALISM RESEARCH IN POLITICAL ECONOMY Series Editor: Paul Zarembka State University of New York at Buffalo, USA Recent Volumes: Volume 24: Transitions in Latin America and in Poland and Syria À Edited by P. Zarembka Volume 25: Why Capitalism Survives Crises: The Shock Absorbers À Edited by P. Zarembka Volume 26: The National Question and the Question of Crisis À Edited by P. Zarembka Volume 27: Revitalizing Marxist Theory for Today’s Capitalism À Edited by P. Zarembka and R. Desai Volume 28: Contradictions: Finance, Greed, and Labor Unequally Paid À Edited by P. Zarembka Volume 29: Sraffa and Althusser Reconsidered; Neoliberalism Advancing in South Africa, England, and Greece À Edited by P. Zarembka Volume 30A: Theoretical Engagements In Geopolitical Economy À Edited by Radhika Desai Volume 30B: Analytical Gains of Geopolitical Economy À Edited by R. Desai Volume 31: Risking Capitalism À Edited by Susanne Soederberg Volume 32 Return of Marxian Macro-Dynamics in East Asia À Edited by M. Ishikura, S. Jeong, and M. Li Volume 33 Environmental Impacts of Transnational Corporations in the Global South À Edited by Paul Cooney and William Sacher Freslon EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD GENERAL EDITOR Paul Zarembka State University of New York at Buffalo, USA EDITORIAL BOARD Paul Cooney Jie Meng Universidad Nacional de General Fudan University, Shanghai, People’s Sarmiento, Argentina Republic of China Radhika Desai Isabel Monal University of Manitoba, Canada University of Havana, Cuba Thomas Ferguson -

Economic Development As the Task for Russian Economic Thought of the 19Th – 20Th Centuries

Denis Melnik National Research University Higher School of Economics (Moscow, Russia) [email protected] The Strive for Progress: Economic Development as the Task for Russian Economic Thought of the 19th – 20th centuries 1. Historical reconstructions of the path made by economic thought in Russia not rarely chose for the reference point some features allegedly inherent to the “spirit” of Russian culture or to Russian national “soul” (hence to Russian economists). Without entering the discussion on plausibility of such an approach, a we may indicate another reference point external to the realm of idealism. Since its inception, Russian economic science faced the problem of backwardness, of lagging behind the advanced economies of the world (or “the West”, as they still commonly referred to in Russian public discourse). That problem directly or indirectly affected the major part of the debates on economic theory and economic policy and posed the challenge before Russian economists of the past two centuries regardless their cultural or theoretical backgrounds or specific historical contexts. The paper is not intended to present a history of Russian economic thought. It is focused on some major debates that marked its course: the debates of the 1890s between Russian populists (Narodinks) and Marxists; the debates of the 1920s; the debates that preceded to and coincided with the crash of Soviet economy and the launch of market reforms. Their content as well as the approaches of the participants naturally differed. But, it seems plausible to propose the following preliminary hypothesis: the nature and outcomes of the debates were very much influenced by participants’ task to secure Russia’s road to progress by means of economic development. -

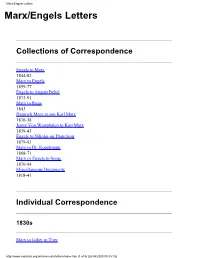

Marx/Engels Letters Marx/Engels Letters

Marx/Engels Letters Marx/Engels Letters Collections of Correspondence Engels to Marx 1844-82 Marx to Engels 1859-77 Engels to August Bebel 1873-91 Marx to Ruge 1843 Heinrich Marx to son Karl Marx 1836-38 Jenny Von Westphalen to Karl Marx 1839-43 Engels to Nikolai-on Danielson 1879-93 Marx to Dr. Kugelmann 1868-71 Marx or Engels to Sorge 1870-94 Miscellaneous Documents 1818-41 Individual Correspondence 1830s Marx to father in Trier http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/letters/index.htm (1 of 5) [26/08/2000 00:28:15] Marx/Engels Letters November 10, 1837 1840s Marx to Carl Friedrich Bachman April 6, 1841 Marx to Oscar Ludwig Bernhard Wolf April 7, 1841 Marx to Dagobert Oppenheim August 25, 1841 Marx To Ludwig Feuerbach Oct 3, 1843 Marx To Julius Fröbel Nov 21, 1843 Marx and Arnold Ruge to the editor of the Démocratie Pacifique Dec 12, 1843 Marx to the editor of the Allegemeine Zeitung (Augsburg) Apr 14, 1844 Marx to Heinrich Bornstein Dec 30, 1844 Marx to Heinrich Heine Feb 02, 1845 Engels to the communist correspondence committee in Brussels Sep 19, 1846 Engels to the communist correspondence committee in Brussels Oct 23, 1846 Marx to Pavel Annenkov Dec 28, 1846 1850s Marx to J. Weydemeyer in New York (Abstract) March 5, 1852 1860s http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/letters/index.htm (2 of 5) [26/08/2000 00:28:15] Marx/Engels Letters Marx to Lasalle January 16, 1861 Marx to S. Meyer April 30, 1867 Marx to Schweitzer On Lassalleanism October 13, 1868 1870s Marx to Beesly On Lyons October 19, 1870 Marx to Leo Frankel and Louis Varlin On the Paris Commune May 13, 1871 Marx to Beesly On the Commune June 12, 1871 Marx to Bolte On struggles witht sects in The International November 23, 1871 Engels to Theodore Cuno On Bakunin and The International January 24, 1872 Marx to Bracke On the Critique to the Gotha Programme written by Marx and Engels May 5, 1875 Engels to P. -

Money and Capital As Competing Media of Exchange

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Research Department Staff Report 341 August 2004 Money and Capital as Competing Media of Exchange Ricardo Lagos∗ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and New York University Guillaume Rocheteau∗ Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland and Australian National University ABSTRACT We construct a model where capital competes with fiat money as a medium of exchange, and we establish conditions on fundamentals under which fiat money can be both valued and socially beneficial. When the socially efficient stock of capital is too low to provide the liquidity agents need, they overaccumulate productive assets to use as media of exchange. When this is the case, there exists a monetary equilibrium that dominates the nonmonetary one in terms of welfare. Under the Friedman Rule, fiat money provides just enough liquidity so that agents choose to accumulate the same capital stock a social planner would. ∗We thank Randall Wright and seminar participants at the Australian National University, University of Paris 2, University of Sydney and the 2003 Meetings of the Society for Economic Dynamics. Lagos thanks the C.V. Starr Center for Applied Economics at NYU for financial support. Rocheteau has benefitted from the Summer Research Grant scheme of the School of Economics of the Australian National University. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. 1Introduction We study an economy where real assets (capital goods) compete with fiat money as a medium of exchange, and we address the following questions: Can fiat money be valued — and useful to society — when real assets can be used as means of payment? Does the production of real assets provide enough liquidity to the economy? How do economies respond to liquidity shortages in the absence of fiat money? We adopt the search-theoretic approach of Kiyotaki and Wright (1989, 1993) since it is well- suited to study which objects endogenously emerge as media of exchange.