MARX E OS OUTROS Jean Tible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tugan-Baranowsky and Effective Demand

Science & Society, Vol. 71, No. 2, April 2007, 227-242 Tugan-Baranowsky and Effective Demand JOHN MIUOS and DIMITRIS SOTIROPOULOS ABSTRACT: Tugan-Baranowsky criticized underconsuption cri- sis theories on the hasis of Marx's reproduction schemes in Vol. II of Capital. However, he incorporated in his analysis the "ahsolute immiseration thesis," and claimed that "proportional- ity" between production sectors would exclude any possibility of crisis, despite the supposedly continuous fall in mass consump- tion. This approach allows for a Keynesian interpretation of Marx's theory of expanded reproduction of social capital, accord- ing to which a constantly increasing investment demand may always compensate for the lacking demand for consumer goods. In contrast to Keynesian approaches, the ultimate "cause" of an economic crisis is found to be not "lack of demand" but "lack of surplus value," in the sense that the totality of capitalist contra- dictions renders capital unable to exploit labor at the level of exploitation that is required for sustaining profitability rates. HE UKRAINIAN ECONOMIST Professor Mikhail von Tugan- Baranowsky (1865-1919) is mainly known as a critical expo- Tnent of Marx's theory and method, who first formulated a radical critique of underconsumption theories (Milios, 1994; Milios, et at, 2002) and also laid the foundation of what is nowadays known as the Surplus Approach School (Ramos-Martinez, 2000). In this paper we are going to critically discuss the Keynesian interpretation and use of Tugan-Baranowsky's arguments and theoretical contra- dictions, which aims at turning him into an early formulator of the "effective demand principle" and thus an (immature) exponent of modern (Keynesian) underconsumptionism. -

Marx and History: the Russian Road and the Myth of Historical Determinism

Ciências Sociais Unisinos 57(1):78-86, janeiro/abril 2021 Unisinos - doi: 10.4013/csu.2021.57.1.07 Marx and history: the Russian road and the myth of historical determinism Marx e a história: a via russa e o mito do determinismo histórico Guilherme Nunes Pires1 [email protected] Abstract This paper aims to point out the limits of the historical determinism thesis in Marx’s thought by analyzing his writings on the Russian issue and the possibility of a “Russian road” to socialism. The perspective of historical determinism implies that Marx’s thought is supported by a unilinear view of social evolution, i.e. history is understood as a succes- sion of modes of production and their internal relations inexorably leading to a classless society. We argue that in letters and drafts on the Russian issue, Marx opposes to any attempt associate his thought with a deterministic conception of history. It is pointed out that Marx’s contact with the Russian populists in the 1880s provides textual ele- ments allowing to impose limits on the idea of historical determinism and the unilinear perspective in the historical process. Keywords: Marx. Historical Determinism. Unilinearity. Russian Road. Resumo O objetivo do presente artigo é apontar os limites da tese do determinismo histórico no pensamento de Marx, através da análise dos escritos sobre a questão russa e a possibilidade da “via russa” para o socialismo. A perspectiva do determinismo histórico compreende que o pensamento de Marx estaria amparado por uma visão unilinear da evolução social, ou seja, a história seria compreendida por uma sucessão de modos de produção e suas relações internas que inexoravelmente rumaria a uma sociedade sem classes sociais. -

Lenin As a Development Economist: a Study in Application of Marx's Theory

Russian Journal of Economics 7 (2021) 34–49 DOI 10.32609/j.ruje.7.57963 Publication date: 31 March 2021 www.rujec.org Lenin as a development economist: A study in application of Marx’s theory in Russia Denis V. Melnik* HSE University, Moscow, Russia Abstract The paper provides an interpretation of Lenin’s earliest contributions (made in 1893–1899) to the study of economic development. In the 1890s, Lenin joined young Marxist intellectu- als in their fight against the Narodnik economists, who represented the approach prevalent among the Russian radical intelligentsia in the 1870s–1880s. That was the fight over the right to control the Marxist narrative in Russia. Lenin elaborated his theoretical interpretation of Marxism as applied to the contentious issues of Russia’s economic development. The paper outlines the context of Lenin’s activity in the 1890s. It suggests that the main theoretical challenge to “orthodox Marxist” intellectuals in applying Marx’s theory to Russia stemmed not from their designated opponents, but from Marx himself, who presented two divergent scenarios — the dynamic and the breakdown — for capitalist development. Lenin provided an analytical substantiation for the dynamic one but eventually allowed for consideration of structural heterogeneity in the development process. This resulted in the notion of uneven- ness, on which he would rely upon later, in his studies of imperialism. The paper also briefly considers the place of Lenin’s early development studies in his legacy. Keywords: Lenin, Marxism, Marxism in Russia, theories of economic development, Marxist theory of accumulation. JEL classification: B14, B24, B31. 1. Introduction The amount of literature dedicated to Lenin is vast. -

RESEARCH in POLITICAL ECONOMY Series Editor: Paul Zarembka State University of New York at Buffalo, USA

CLASS HISTORY AND CLASS PRACTICES IN THE PERIPHERY OF CAPITALISM RESEARCH IN POLITICAL ECONOMY Series Editor: Paul Zarembka State University of New York at Buffalo, USA Recent Volumes: Volume 24: Transitions in Latin America and in Poland and Syria À Edited by P. Zarembka Volume 25: Why Capitalism Survives Crises: The Shock Absorbers À Edited by P. Zarembka Volume 26: The National Question and the Question of Crisis À Edited by P. Zarembka Volume 27: Revitalizing Marxist Theory for Today’s Capitalism À Edited by P. Zarembka and R. Desai Volume 28: Contradictions: Finance, Greed, and Labor Unequally Paid À Edited by P. Zarembka Volume 29: Sraffa and Althusser Reconsidered; Neoliberalism Advancing in South Africa, England, and Greece À Edited by P. Zarembka Volume 30A: Theoretical Engagements In Geopolitical Economy À Edited by Radhika Desai Volume 30B: Analytical Gains of Geopolitical Economy À Edited by R. Desai Volume 31: Risking Capitalism À Edited by Susanne Soederberg Volume 32 Return of Marxian Macro-Dynamics in East Asia À Edited by M. Ishikura, S. Jeong, and M. Li Volume 33 Environmental Impacts of Transnational Corporations in the Global South À Edited by Paul Cooney and William Sacher Freslon EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD GENERAL EDITOR Paul Zarembka State University of New York at Buffalo, USA EDITORIAL BOARD Paul Cooney Jie Meng Universidad Nacional de General Fudan University, Shanghai, People’s Sarmiento, Argentina Republic of China Radhika Desai Isabel Monal University of Manitoba, Canada University of Havana, Cuba Thomas Ferguson -

Economic Development As the Task for Russian Economic Thought of the 19Th – 20Th Centuries

Denis Melnik National Research University Higher School of Economics (Moscow, Russia) [email protected] The Strive for Progress: Economic Development as the Task for Russian Economic Thought of the 19th – 20th centuries 1. Historical reconstructions of the path made by economic thought in Russia not rarely chose for the reference point some features allegedly inherent to the “spirit” of Russian culture or to Russian national “soul” (hence to Russian economists). Without entering the discussion on plausibility of such an approach, a we may indicate another reference point external to the realm of idealism. Since its inception, Russian economic science faced the problem of backwardness, of lagging behind the advanced economies of the world (or “the West”, as they still commonly referred to in Russian public discourse). That problem directly or indirectly affected the major part of the debates on economic theory and economic policy and posed the challenge before Russian economists of the past two centuries regardless their cultural or theoretical backgrounds or specific historical contexts. The paper is not intended to present a history of Russian economic thought. It is focused on some major debates that marked its course: the debates of the 1890s between Russian populists (Narodinks) and Marxists; the debates of the 1920s; the debates that preceded to and coincided with the crash of Soviet economy and the launch of market reforms. Their content as well as the approaches of the participants naturally differed. But, it seems plausible to propose the following preliminary hypothesis: the nature and outcomes of the debates were very much influenced by participants’ task to secure Russia’s road to progress by means of economic development. -

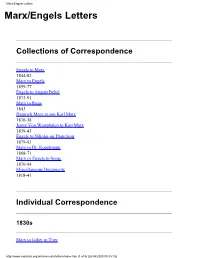

Marx/Engels Letters Marx/Engels Letters

Marx/Engels Letters Marx/Engels Letters Collections of Correspondence Engels to Marx 1844-82 Marx to Engels 1859-77 Engels to August Bebel 1873-91 Marx to Ruge 1843 Heinrich Marx to son Karl Marx 1836-38 Jenny Von Westphalen to Karl Marx 1839-43 Engels to Nikolai-on Danielson 1879-93 Marx to Dr. Kugelmann 1868-71 Marx or Engels to Sorge 1870-94 Miscellaneous Documents 1818-41 Individual Correspondence 1830s Marx to father in Trier http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/letters/index.htm (1 of 5) [26/08/2000 00:28:15] Marx/Engels Letters November 10, 1837 1840s Marx to Carl Friedrich Bachman April 6, 1841 Marx to Oscar Ludwig Bernhard Wolf April 7, 1841 Marx to Dagobert Oppenheim August 25, 1841 Marx To Ludwig Feuerbach Oct 3, 1843 Marx To Julius Fröbel Nov 21, 1843 Marx and Arnold Ruge to the editor of the Démocratie Pacifique Dec 12, 1843 Marx to the editor of the Allegemeine Zeitung (Augsburg) Apr 14, 1844 Marx to Heinrich Bornstein Dec 30, 1844 Marx to Heinrich Heine Feb 02, 1845 Engels to the communist correspondence committee in Brussels Sep 19, 1846 Engels to the communist correspondence committee in Brussels Oct 23, 1846 Marx to Pavel Annenkov Dec 28, 1846 1850s Marx to J. Weydemeyer in New York (Abstract) March 5, 1852 1860s http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/letters/index.htm (2 of 5) [26/08/2000 00:28:15] Marx/Engels Letters Marx to Lasalle January 16, 1861 Marx to S. Meyer April 30, 1867 Marx to Schweitzer On Lassalleanism October 13, 1868 1870s Marx to Beesly On Lyons October 19, 1870 Marx to Leo Frankel and Louis Varlin On the Paris Commune May 13, 1871 Marx to Beesly On the Commune June 12, 1871 Marx to Bolte On struggles witht sects in The International November 23, 1871 Engels to Theodore Cuno On Bakunin and The International January 24, 1872 Marx to Bracke On the Critique to the Gotha Programme written by Marx and Engels May 5, 1875 Engels to P. -

Marx's Furtherwork on Capital After Publishing Volume I

chapter 4 Marx’s Further Work on Capital after Publishing Volume i: On the Completion of Part ii of the mega² Carl-Erich Vollgraf When in 1908 the young Austromarxist Otto Bauer published an essay on Marx’s Capital in the journal Die Neue Zeit, he titled it ‘The History of a Book’. His idea was that each generation has its own Marx – and not just because each historical epoch poses different questions. After all, new texts by Marx continued to become available all the time. His own generation, he noted, had access to all three volumes of Capital. So, with Marx’s overall plan in view, it was obvious that one could now read Capital in a different way than the previous generation, which had to make do with Volume i only.1 Bauer could hardly predict what the situations of future generations would be, yet he anticipated them pretty well. Again and again there were new upheavals in society, but also new texts by Marx, new interpretations in different settings, and revisions – right up to the present day. In the years after 1989, with the collapse of state socialism, the literary mar- ket was for a while filled with obituaries in the style of ‘what remains of Marx now?’, but then it quickly turned out that he had never written any book about socialism. Subsequently Marx has joined the real classics. Everyone can now approach his work freely, and interpret its content in new and different ways. Even those who are well-read return to Marx, to confront the new dimen- sions of capitalist accumulation and the unbridled pursuit of profits. -

Redalyc.MARX E OS OUTROS

Lua Nova ISSN: 0102-6445 [email protected] Centro de Estudos de Cultura Contemporânea Brasil Tible, Jean MARX E OS OUTROS Lua Nova, núm. 91, enero-abril, 2014, pp. 199-229 Centro de Estudos de Cultura Contemporânea São Paulo, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=67331154008 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto MARX E OS OUTROS Jean Tible para Mauro William Barbosa de Almeida Era Marx eurocêntrico? Propõe-se aqui, para responder a esta pergunta, uma leitura dos seus escritos que abordam formações sociais e econômicas, lutas e acontecimentos que vão além da Europa Ocidental. Entre os estágios de desenvolvimento e a crítica do colonialismo Um primeiro aspecto dos escritos de Marx aqui estudados é sua busca em desvendar os estágios de desenvolvimento e da evolução social e sua correlata apreensão de situações concretas. Em A ideologia alemã, Marx e Engels esboçam uma sucessão histórica dos modos de produção. Para os autores, “os vários estágios de desenvolvimento da divisão do trabalho são, apenas, outras tantas formas diversas de propriedade”. O primeiro estágio é o da propriedade tribal, no qual a estrutura social corresponde à estrutura da família e a subsis- tência é garantida pela caça e pesca, pela criação de animais e, às vezes, pela agricultura. Não há desenvolvimento da pro- dução e a divisão de trabalho é elementar. A segunda forma situa-se na Antiguidade e sua propriedade é comunal e estatal. -

Marx at the Margins: on Nationalism, Ethnicity, and Non-Western Societies

Marx at the Margins Marx at the Margins On Nationalism, Ethnicity, and Non-Western Societies Kevin B. Anderson The University of Chicago Press Chicago & London Kevin B. Anderson is professor of sociology and political science at the University of California–Santa Barbara. He has edited four books and is the author of Lenin, Hegel, and Western Marxism: A Critical Study and, with Janet Afary, Foucault and the Iranian Revolution: Gender and the Seductions of Islamism. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2010 Printed in the United States of America 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-01982-6 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-01983-3 (paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-01982-9 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-226-01983-7 (paper) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Anderson Kevin, 1948– Marx at the margins : on nationalism, ethnicity, and non-western societies / Kevin B. Anderson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-01982-6 (cloth : alk.paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-01982-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-01983-3 (pbk : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-01983-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Marx, Karl, 1818–1883— Political and social views. 2. Nationalism. 3. Ethnicity. I. Title JC233.M299A544 2010 320.54—dc22 2009034187 a The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, -

Marcello-Musto-Another-Marx-Early

A n o t h e r M a r x i Also available from Bloomsbury A e s t h e t i c M a r x , edited by Samir Gandesha and Johan Hartle Capitalism: Th e Reemergence of a Historical Concept , edited by Jürgen Kocka and Marcel van der Linden Workers Unite! Th e International 150 Years Later , edited by Marcello Musto ii Another Marx Early Manuscripts to the International M a r c e l l o M u s t o Translated by Patrick Camiller iii BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3DP, UK BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2018 Copyright © Marcello Musto, 2018 Marcello Musto has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Author of this work. For legal purposes the Notice on p. x constitutes an extension of this copyright page. Cover design: Adriana Brioso Cover image: Karl Marx (Photo by Time Life Pictures/Mansell/The LIFE Picture Collection/ Getty Images). Manuscript page of an article by Karl Marx, published 25 January 1873 in The International Herald newspaper (photo by Getty Images). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. -

Isaac Deutscher 1948 Marx and Russia the Attitudes of Marx And

Isaac Deutscher 1948 Marx and Russia Source: BBC Third Programme talk, November 1948, republished in Isaac Deutscher, Heretics and Renegades and Other Essays (Hamish and Hamilton, London, 1955). Scanned and prepared for the Marxist Internet Archive by Paul Flewers. The attitudes of Marx and Engels towards Russia and their views on the prospects of Russian revolution form a curious topic in the history of socialism. Did the founders of scientific socialism have any premonition of the great upheaval in Russia that was to be carried out under the sign of Marxism? What results did they expect from the social developments inside the Tsarist Empire? How did they view the relationship between revolutionary Russia and the West? One can answer these questions more fully now on the basis of the correspondence between Marx, Engels and their Russian contemporaries, published by the Marx – Engels – Lenin Institute in Moscow last year. This correspondence covers nearly half a century. It opens with Marx’s well-known letters to Annenkov [1] of 1846. It closes with the correspondence between Engels and his Russian friends in 1895. The volume also contains nearly fifty letters published for the first time. Among the Russians who kept in touch with Marx and Engels there were men and women belonging to three generations of revolutionaries. In the 1840s the revolutionary movement in Russia had an almost exclusively intellectual and liberal character. It was based on no social class or popular force. To that epoch belonged Marx’s early correspondents, Annenkov, Sazonov [2] and a few others. Marx explained to them his philosophy and his economic ideas, but engaged in no discussion on revolution in Russia. -

The United States of Marx and Marxism: Introduction

The United States of Marx and Marxism: Introduction Dennis Büscher-Ulbrich and Marlon Lieber On the Actuality of Marx The 200th anniversary of the birth of German philosopher Karl Marx on May 5, 1818 arguably gives reason to critically examine the influence of Marx’s thought on the United States. While the anniversary of Marx’s birth seems to us reason enough to revisit his thought, there are various other reasons that convince us that this project is timely—and maybe even necessary. Of course, the lasting effects of the unresolved financial and economic crisis that began with the bursting of the U.S. housing bubble in 2007 have made the turn to heterodox approaches to eco- nomics more attractive for many. The ongoing global crisis of accumulation has led to the re-emergence in public discourse of the idea that capitalism could end. For those who believe that “there is no alternative,” it gave way to a latent sense of a crisis of civilization. For many, it was proof of the notion that capitalist moder- nity has an intrinsic tendency toward crisis. For some, this generated the welcome prospect of capitalism’s ultimate demise. The focus on the inequalities produced by the capitalist mode of production found in Marx, and the insistence on the sys- temic character of crisis, where the abstract-seeming “internal contradictions of capital” ceaselessly and necessarily (re)produce concrete and intersecting social antagonisms, began to appeal to wide circles of academics (Harvey 9). But not just academics: While it may be surprising for some that “crises are essential to the reproduction of capitalism,” it is hardly surprising that a crisis of this extent “shake[s] our mental conceptions of the world and of our place in it to the very core” (Harvey ix-x).