Download Date 08/10/2021 06:15:53

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aza E Zainab

Aza E Zainab Compiled by Sakina Hasan Askari nd 2 Edition 1429/2008 1 Contents Introduction 3 Karbala to Koofa 8 Bazaare Koofa 17 Darbar e Ibn Ziyad 29 Kufa to Sham 41 News Reaching Medina 51 Qasr e Shireen 62 Bazaare Sham 75 Darbar e Yazeed 87 Zindan e Sham 101 Shahadat Bibi Sakina 111 Rihayi 126 Daqila Karbala 135 Arbayeen 147 Reaching Medina 164 At Rauza e Rasool 175 Umm e Rabaab‟s Grief 185 Bibi Kulsoom 195 Bibi zainab 209 RuqsatAyyam e Aza 226 Ziarat 240 Route Karbala to Sham 242 Index of First Lines 248 Bibliography 251 2 Introduction Imam Hussain AS, an ideal for all who believe in righteous causes, a gem of the purest rays, a shining light, was martyred in Karbala on the tenth day of Moharram in 61 A.H. The earliest examples of lamentations for the Imam have been from the family of the Holy Prophet SAW. These elegies are traced back to the ladies of the Prophet‟s household. Poems composed were recited in majalis, the gatherings to remember the events of Karbala. The Holy Prophet SAW, himself, is recorded as foretelling the martyrdom of his grandson Hussain AS at the time of his birth. In that first majlis, Imam Ali AS and Bibi Fatima AS, the parents of Imam Hussain AS , heard from the Holy Prophet about the martyrdom and wept. Imam Hasan AS, his brother, as he suffered from the effects of poison administered to him, spoke of the greater pain and agony that Imam Hussain would suffer in Karbala. -

Positionality and Feminisms of Women Within Sufi Brotherhoods of Senegal Georgia Collins Humboldt State University

ideaFest: Interdisciplinary Journal of Creative Works and Research from Humboldt State University Volume 1 ideaFest: Interdisciplinary Journal of Creative Works and Research from Humboldt State Article 3 University 2016 Positionality and Feminisms of Women within Sufi Brotherhoods of Senegal Georgia Collins Humboldt State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/ideafest Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, African Studies Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Islamic Studies Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, Rural Sociology Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Collins, Georgia (2016) "Positionality and Feminisms of Women within Sufi rB otherhoods of Senegal," ideaFest: Interdisciplinary Journal of Creative Works and Research from Humboldt State University: Vol. 1, Article 3. Available at: http://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/ideafest/vol1/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in ideaFest: Interdisciplinary Journal of Creative Works and Research from Humboldt State University by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

Abduh, Mohammad, 98 Abou Ubaydata Mosque (Unite 26), 61

INDEX Abduh, Mohammad, 98 111,113-14,116,118-21,123,130, Abou Ubaydata mosque (Unite 26), 61, 65 132n4,162n157,214,239-40,267; accommodation, 3, 5-6, 8, 37, 76-77, 80, lack of, in The Gambia, 142, 144, 152, 82-83, 87n13,91,99, 240, 245, 248 156 Afghani, Jamal AI-Din AI-, 119 Arabisantes (female scholars), 215 African Islam, 1-2, 132n3, 140, 156, 157n8, Arabisants, 65, 69n34 190-91; Islam in Africa vs., 6, 114 Arab Muslim world, 2, 7,11, 15n18 , 61-62, Africanization ofIslam, Islamization ofAfrica 79,156,215,258-59,265,268. See vs.,3,91-92,133n28 alsospecific countries and regions Afrique Nouvelle (newspaper), 119 Arberry, A. J., 87n46 Afrique Occidentale Francaise (AOF), 29, architecture, 9, 63-65 42n42,44n66 Archives Nationales de France Section Ahmadinejad, President, 117, 134n44 d'Outer-Mer (ANFOM), 44n67 AI-Azhar University (Cairo), 32,119 aristocracy, 4,75,77-78, 86n15, 91, 93 AI-Bakri,40n5, 41n24, 86n13 Asad, Talal, 98,112-13, 132nn alcohol and tobacco, 8, 53, 96,101,263 Ashura,121 AI-Falah mosque (Dakar), 61 Ashura conference, 124, 125, 135n78 Algeria, 118, 134n63, 214 assimilation, 6 AI-Ghazali,98-100 Association des Eleveset Etudiants Musulmans AI-Hajj Ibrahim Derwiche Mosque (Dakar), du Senegal (AEEMS), 215, 218-19, 127-28, 128-29 223,226 Ali, Imam, 116, 126-27, 135n86 Association des Etudiants Musulmans de Alidou, Ousseina, 228nl i'Universite de Dakar (AEMUD), 215, Almada, Andre Alvares d' , 40n12 217-21,224,226 Almoravid movement, 22, 40n5, 77, 132n17 Association des Femmes de la Cite de Ngalele, alms seeking, 25, 34-35, 37-38 57-58 Al-Naqar, Umar, 40n5 Association des]eunes Mourides, 244 AI-Sadi,22 Association Fatima Zahra, 123 Alvares,Andre, 172 associationist Islam, 215-16, 240-45, Aly Yacine (PSLF) Centre Islamique de 249n24 Rechercheet d'Information, 114, 121 Association Musulmane des Etudiants 23, 122, 135n73. -

Terànga and the Art of Hospitality: Engendering the Nation, Politics, and Religion in Dakar, Senegal

TERÀNGA AND THE ART OF HOSPITALITY: ENGENDERING THE NATION, POLITICS, AND RELIGION IN DAKAR, SENEGAL By Emily Jenan Riley A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Anthropology - Doctor of Philosophy 2016 ABSTRACT TERÀNGA AND THE ART OF HOSPITALITY: ENGENDERING THE NATION, POLITICS AND RELIGION IN DAKAR, SENEGAL By Emily Jenan Riley Senegal, a Muslim majority and democratic country, has long coined itself as "le pays de la terànga" (Land of Hospitality). This dissertation explores the central importance of terànga– the Wolof word which encapsulates the generous and civic-minded qualities of individuals – to events such as weddings and baptisms, women’s political process, as well as everyday calculated and improvisational social encounters. Terànga is both the core symbol, for many, of Senegalese nationalism and collective identity, and the source of contentious and polarizing debates surrounding its qualities and meanings. The investigation of terànga throughout this dissertation exposes the complexities of social and gender ideologies and practices in Senegal. In addition, this dissertation aspires to investigate the subjectivities, and conditions of Senegalese women as well as their contributions to the social, religious, and political realities of contemporary Senegal, and Dakar more specifically. This dissertation focuses on how terànga is debated, talked about, and performed by several groups. First, it investigates the public discourses of terànga as a gendered symbol of national culture and its central importance to the construction of female subjects in their navigation of courtship, marriage, and family relations. Second, an exposé of family ceremonies and the women who conduct them, demonstrates generational shifts in the interpretation and value given to the process of terànga in a contemporary moment where daughters are redefining its meaning from that of their mother's generation. -

New Wolof Book

! AAY NAA CI WOLOF!! TRAINEE WOLOF MANUAL! ! ! ! ! PEACE CORPS SENEGAL Revised edition August 2012 1 ! About this edition This is edition of this book. The first edition was written by me, Bamba Diop, after a great work of the whole language team and a group of volunteers to determine the content and the design. After a year of use of the first edition, our Country Director, Chris Hedrick who learned Pullo Fuuta from Mido Waawi Pulaar, reflected on the book and compare both. We discussed and came up with improving the book. This second edition is produced by Bamba Diop, language coordinator with editing by David Lothamar and Jackie Allen, volunteers. This edition is an adaptation of the second edition to the healt, AG & AGFO. The second edition was reinforced by ideas from Mido Waawi Pulaar by Herb Caudill (PCV Guinea 1997-99) and Ousmane Besseko Diallo (TM Guinea), Ndank-Ndank, An Introduction to Wolof Culture by Molly Melching. We suggest that this approach – collaboration between a Peace Corps volunteer who has learned the language and a trainer who speaks the language is the best way to come up with a manual that is relevant, useful, and user-friendly while remaining accurate. This is a work in progress, and we welcome advice and criticism from all sides: trainers, trainees, volunteers PC staff and others. This manual will be downloaded at www.pcsenegal.org. We thank all the people who have brought their inputs for the fulfillment of this manual and its improvement particularly trainees and LCFs who have been using it through their criticism. -

"Bad Guys": Towards Dialogue with Central Mali's Jihadists

Speaking with the “Bad Guys”: Toward Dialogue with Central Mali’s Jihadists $IULFD5HSRUW1_0D\ +HDGTXDUWHUV ,QWHUQDWLRQDO&ULVLV*URXS $YHQXH/RXLVH %UXVVHOV%HOJLXP 7HO )D[ EUXVVHOV#FULVLVJURXSRUJ Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Crisis in Central Mali ................................................................................................. 3 A. The Katiba Macina: An Ingrained Insurgency .......................................................... 3 B. Intercommunal Violence ........................................................................................... 5 C. The Limits of Counter-terrorism and Development ................................................. 7 D. Breaking the Taboo .................................................................................................... 10 III. Obstacles to Dialogue ....................................................................................................... 12 A. Are Jihadist Demands “Exceptional”? ....................................................................... 12 B. The Katiba Macina’s Outside Connections ................................................................ 14 C. Domestic and Foreign Pressures .............................................................................. -

Brotherhood Solidarity and the (Re) Negotiation of Identity Among Senegalese Migrants in Durban

BROTHERHOOD SOLIDARITY AND THE (RE) NEGOTIATION OF IDENTITY AMONG SENEGALESE MIGRANTS IN DURBAN BILOLA NICOLINE FOMUNYAM COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES, SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a PhD in anthropology at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. SUPERVISOR: Prof. VB OJONG JULY 2014 DECLARATION I, Bilola Nicoline Fomunyam, hereby declare that this thesis is my own unaided work and has not been submitted previously for any degree or examination in any other university. All references, citations, and borrowed ideas have been duly acknowledged. Bilola Nicoline Fomunyam (208519680) 07/10/14 i DEDICATION This work is dedicated to God almighty for his grace and favour in my life and to my brother Divine langmia Fomunyam whose personal integrity and uncompromising ethical stance is a beacon of light as well as a living legacy for me. What would I have done without a brother like you. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are several weave of circumstances as well as prompt of kin that form the tapestry of actualities and actors that worked together to lead to the realization of this dissertation. Even though only my name is written on the cover page of this work, many people contributed to its creation by walking some of the way with me. The words I offer here can never fully express the immense gratitude I feel towards the people who have gently accompanied me to where I now find myself, where I am able to say THANK YOU. Notably, I must begin by thanking my Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ for ‘bringing me to it and then seeing me through it’. -

Liste Des Stagiaires

LISTE DES STAGIAIRES Branche : REGIE Nom et Prénom Coordonnées HAY AL WAHDA N° 1802 OUARZAZATE ABDELATIF AL MASOUDY GSM: 06 66 35 20 63 [email protected] 35 RUE 1 GROUPE 7 HAY DOUMA SIDI MOUMEN JDID ABDELHAK BEN MOHAMED CASABLANCA Tél: 06-72-57-22-02 [email protected] Rue El Oued El Kabir N° 60 Semlalia Guéliz MARRAKECH ABDELHAKIM ALAHIANE 05 44 43 25 17 06 62 05 36 23 HAY EL MASJID RUE 12 N° 3 CASABLANCA ABDELLAH TOUGHABI 06 77 83 49 86 [email protected] N° 84, HAY EL QODS OUARZAZATE ABDELLATIF ATTACH GSM:0651 67 35 93; 0613 15 71 08; 0624 88 36 58 [email protected] 16,RUE KHALED BEN OUALID DAKHLA,AGADIR ABDELLATIF BENNANI SMIRES TEL: 06 73 21 59 45 [email protected] AMAL 4 IMM 8 N° BERNOUSSI ABDELMOULA ABOUYASSINE CASABLANCA SAADA 5 N° 306 LAMHAMID MARRAKECH ABDELMOULA TERKIBA 06 24 67 83 56 [email protected] Page 1 REGIE Atelier d'Art, 68 Rue ABDELMOUNAIM BENHAYOUN Dar el Bacha Sidi Abdelaziz 6 medina MARRAKECH 06 67 59 74 16 CITE DES OFFICIER N° 10 OUARZAZATE ABDELMOUNAIM DAMIR 06 58 78 89 12 [email protected] 93 BIS ALLEE DES CASUARINAS AIN SEBAA 20250 CASABLANCA ABDELMOUNIM AMZIL Tél: 06-64-20-03-84 [email protected] [email protected] N° 5 RUE ALLAL JNANE ZITOUNE QU SAADA SAFI ABDELMOUTALIB HAMADA 06 99 71 94 86 [email protected] RUE MY ABDELLAH AMGHAR N°36 LOT ENNAKHIL ABDENNAIM MY JAMAA EL JADIDA 06 65 98 81 34 HAY ANDALOUS ROUTE DE CASA N° 82 MARRAKECH ABDERRAZAK BARNOUSSI 06 76 04 52 69 [email protected] Bloc 17 N° 20 Youssoufia Ouest Rabat ABDERRAZZAK JAABOUK GSM : 06 61 -

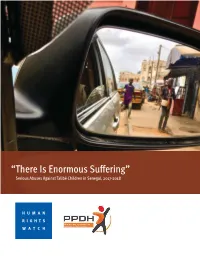

There Is Enormous Suffering” Serious Abuses Against Talibé Children in Senegal, 2017-2018

“There Is Enormous Suffering” Serious Abuses Against Talibé Children in Senegal, 2017-2018 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH “There Is Enormous Suffering” Serious Abuses Against Talibé Children in Senegal, 2017-2018 Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-37380 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-37380 “There Is Enormous Suffering” Serious Abuses Against Talibé Children in Senegal, 2017-2018 Map 1: Locations of Research in Senegal ............................................................................. i Map 2: Talibé Migration Routes .......................................................................................... ii Terminology and Abbreviations ........................................................................................ -

Submission on Forced Child Begging In

January 2019 Anti-Slavery International briefing on Senegal, 5th periodic report (List of Issues): Forced child begging 125th session of the UN Human Rights Committee, 4 to 29 March 2019 I. INTRODUCTION Report content This submission to the Human Rights Committee (hereafter the Committee) provides information relevant to Article 8 on forced child begging of talibés in Senegal, a worst form of child labour. We hope it will inform the Committee’s review of Senegal (List of Issues) and that the areas of concern highlighted here will be reflected in the list of issues submitted to the Government of Senegal ahead of the review. Author of the report Anti-Slavery International, established in 1839 and in consultative status with ECOSOC since 1950, is the oldest international human rights organisation in the world. Today, Anti-Slavery International works to eradicate all contemporary forms of slavery, including bonded labour, forced labour, trafficking in human beings, descent based slavery, the worst forms of child labour, and forced marriage. Methodology The evidence in this submission was gathered through projects delivered in Senegal by the above named organisations, which include a three-pronged approach to tackle child begging through the modernisation of daaras, child protection and access to a regular school curriculum. II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Forced child begging of talibés, a worst form of child labour, continues to be a widespread problem across Senegal. Talibés are children, almost exclusively boys and generally between the ages of five to 15 years, who study in Quranic schools (daaras), which are not part of the formal education sector in Senegal. -

Iom Mauritania

IOM MAURITANIA NEWSLETTER N07 - February 2017 / May 2017 /2017 ©OIM/S.Desjardins THEME ▲ A young woman participating to the caravan of sensitisation on countering violent extremism and irregular migration in the streets ofNouakchott inthestreets migration andirregular extremism violent oncountering ofsensitisation the caravan to participating woman A young ©OIM/S.Desjardins/2017 THE MISSION OF IOM IN MAURITANIA IOM IN 2 WORDS The host agreement between the International Organization Established in 1951, for Migration and the Government of the Islamic Republic of IOM is the United Nations migration agency Mauritania was signed on the 15th of July 2007 in Geneva and ratified on the 7th of July 2008. Nouakchott based with a sub-office in Bassikounou, IOM Mauritania works closely with the Mauritanian Government 165 401 9063 and other partners to reinforce national migration management Member States Offices throughout Staff members capacities and provide assistance to migrants in the country. and 8 Observers the world 95% on the Field The mission is structured around three major axis of intervention: 2 2 9 MIGRANT ASSISTANCE Liaison offices Administrative Regional Offices New York centers Dakar BORDER MANAGEMENTMAURITANIE Addis-Ababa Manilla Nairobi Panama Cairo Pretoria COMMUNITY STABILISATION San Jose Buenos Aires Bangkok Brussels ▼ ► Report about the surface and geographic situation of Mauritania Vienna MAURITANIE 2400 Active projects Headquarter throughout the world with a budget of over 1 billion $ Geneva IOM Mauritania - Newsletter N°7 • February / May 2017 2 LOST BOYS SERIES Chris‘s history1 escape, leaving her oldest child behind, hoping He learned how to read in less than a month. this man would send him to Europe. -

The Assimilation of Traditional Practices in Contemporary Architecture

61 The Assimilation of Traditional Practices in Contemporary Architecture Roland Depret Dakar is a recent city, like all of the coastal Dakar, An Islamic City? Dakar at that time is emptied of its popu cities of West Africa Fifty-six years ago, it lation and of its public transportation had only 40,000 inhabitants. Something on Dakar has a large Moslem majority, on the system. the order of 80 percent of the present order of a million people - but does that As we will see, this importance of Islam is population has been urbanized only for make it an "Islamic" city? expressed in the built-up environment, but one or two generations, and individual and Islam is a basic fact in Senegal, and it is with some specific aspects that are some collective memory is fully aware of the times rather distant from those of other traditional environment; the way of life is intensely felt by the population. Like all Africans in general, the Senegalese are Moslem countries This fact is due as much permeated by it deeply religious To be sure, there are to African particularisms as to the very In all sorts of activities linking it with the remnants of the traditional African perceptible effects of colonization built-up part of the environment, the large religions, "weighted syntheses," depen Like all other great cities, Dakar is an majority of Dakar's population assimilates ding on the case, of animism, of totem ism , arena of struggle, a "contest area," har this traditional past into its contemporary of manism, of naturism, of fetishism and of boring numerous conflicts and internal environment.