Airport Improvement Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V9.5 on Ipad Introduction

Pilot’s Guide to FOREFLIGHT MOBILE 55th Edition Covers ForeFlight Mobile v9.5 on iPad Introduction ...............................................................................................19 iPad Tips ....................................................................................................................................19 Setting-up ForeFlight Mobile ..............................................................21 Planning a Flight ......................................................................................22 Planning a fight using the Flights form ........................................................................22 Destination Services ................................................................................................................................23 Navlog, Briefng, Messages ...................................................................................................................24 Planning a fight on Maps using the Flight Plan Editor ..........................................25 Planning a fight on Maps using Touch .........................................................................26 Planning a fight on Maps using Search ........................................................................27 Scheduled Flight Search on Maps ......................................................................................................29 Airports ........................................................................................................31 About the Design ..................................................................................................................32 -

Massdot Aeronautics Division Offices the Logan Office Center One Harborside Drive, Suite 205N East Boston, MA 02128-2909

MASSACHUSETTS STATEWIDE AIRPORT SYSTEM PLAN MASSDOT AERONAUTICS DIVISION MASSACHUSETTS STATEWIDE AIRPORT SYSTEM PLAN (MSASP) PROJECT MANAGEMENT TEAM (PMT) MEETING #2 MEETING NOTES Thursday, December 10, 2009 (1 PM– 3 PM) MassDOT Aeronautics Division Offices The Logan Office Center One Harborside Drive, Suite 205N East Boston, MA 02128-2909 1. MEETING ATTENDANCE PMT Member Attendees: Member Name Affiliation Chris Willenborg MassDOT Aeronautics, Administrator Denise Garcia MassDOT Aeronautics, Manager of Aviation Planning William Benjamin Former MAC Commissioner Craig Dotlo (via phone) Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) Flavio Leo Massport Russ Maguire Massachusetts Airport Management Association (MAMA) Paul Nelson Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation (EOT) Michelle Ricci (via phone) Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Arthur Robert Massachusetts Office of Business Development (MOBD) Dean Saucier (via phone) National Business Aviation Association (NBAA) Absent PMT Member Attendees: Harold Bevis Delta Airlines / Air Transport Association (ATA) Dan Wolf Cape Air Other Meeting Attendees: Steven Rawding MassDOT Aeronautics, Aviation Planner Katie Servis MassDOT Aeronautics, Environmental Analyst Bob Mallard Airport Solutions Group (ASG) - Study Project Manager Pam Keidel-Adams Wilbur Smith Associates – Project Team Member James Miklas Wilbur Smith Associates – Project Team Member Marc Champigny Louis Berger Group – Project Team Member Nick Stefaniak Louis Berger Group – Project Team Member Jeremy Martelle Louis Berger -

Scalability of the Air Transportation System and Development of Multi-Airport Systems: a Worldwide Perspective

Scalability of the Air Transportation System and Development of Multi-Airport Systems: A Worldwide Perspective by Philippe A. Bonnefoy B. Ing., Mechanical Engineering, École Polytechnique de Montréal, Canada, 2002 S.M., Aeronautics & Astronautics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2005 Submitted to the engineering systems division in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2008 2008 Philippe A. Bonnefoy, All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: ______________________________________________________ Philippe A. Bonnefoy Engineering Systems Division May 30th 2008 Certified by: _____________________________________________________________ R. John Hansman, Professor Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics and Engineering Systems Thesis Supervisor Certified by: _____________________________________________________________ Cynthia Barnhart, Professor Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Engineering Systems Certified by: _____________________________________________________________ Richard de Neufville, Professor Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Engineering Systems Certified by: _____________________________________________________________ Amedeo Odoni, Professor Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics and Civil and Environmental Engineering Accepted -

Chapter 6: System Recommendations

6. System Recommendations 6.1. Introduction This chapter builds on the findings of Chapter 5. System Performance by establishing future performance targets and making recommendations for South Dakota’s aviation system to achieve those future targets. This chapter is organized around the three system goals established at the beginning of the study and includes a review of each goal’s associated performance measures (PMs) to identify gaps in system performance. Performance gaps are determined by comparing the existing performance (presented in Chapter 5) to the future performance targets established by the South Dakota Department of Transportation Office of Aeronautics Services (SDDOT) and stakeholder groups to identify the number of airports, by state role and system-wide, that are not meeting each PM. Evaluating the existing performance against future performance targets provides a list of airports that are deficient in meeting the PM and therefore are candidates for system plan project recommendations. However, it is important to note that while these lists of airports by PM are helpful in understanding the system gaps, resources are limited and therefore an airport’s mention in this chapter is not a guarantee of project funding. For more information on SDSASP recommended projects, including anticipated costs and project priorities, see Chapter 7. System Needs and Project Costs. As a supplement to this recommendations chapter, Appendix E – NPIAS Analysis and Recommendations offers recommendations related to airport inclusion and exclusion from National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems (NPIAS) and changes to ASSET classifications for SDSASP airports. While this information does not pertain directly to the recommendations included in this chapter, it does provide additional context as it relates to system recommendations. -

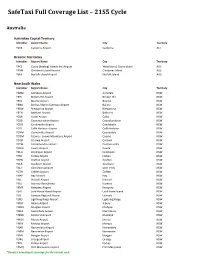

Safetaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Australia Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER -

Feasibility Study for Goderich Municipal Airport (YGD) and Richard W

Feasibility Study for Goderich Municipal Airport (YGD) and Richard W. Levan Municipal Aerodrome (CPR7) FINAL REPORT The Corporation of the County of Huron . January 3rd, 2017 ii Table of Contents Table of Contents .....................................................................................................................iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 6 2. Internal Analysis: Current State of the Airports ............................................................. 6 2.1 Airport Operational Review ................................................................................... 7 2.1.1 Goderich Airport ............................................................................................. 7 2.1.1.1 Infrastructure Review .......................................................................... 7 2.1.1.2 Fuel System and Procedure Review ................................................... 7 2.1.1.3 Operation Review ................................................................................ 7 2.1.1.4 Airport Staff Review ............................................................................ 8 2.1.2 Richard W. Levan Aerodrome ........................................................................ 8 2.1.2.1 Infrastructure Review ........................................................................... -

Fscaptain User's Guide

FSCaptain User's Guide Software Version 1.8.2 June 2020 Version 1.8.2 210 Pages Introduction This manual is written to help you configure and use FSCaptain – an Air Transport Pilot simulation for use with Microsoft’s Flight Simulator 2004, Microsoft’s Flight Simulator X, Dovetail Games’ Flight Simulator X – Steam Edition, and Lockheed-Martin’s Prepar3D (versions 2 - 4). This manual explains everything about the Administrator program in detail, omitting those parts involving us- ing the FCDU communications device while you are flying. FSCaptain is easy to configure and use. This manual is divided into seven main sections: Getting Started -- is as easy as 1 – 2 – 3. This section will help you understand how to install the FCDU device into your aircraft, so you can use them with FSCaptain, and how to start your career flying for one of the airlines provided with the system. Your Career -- will explain how to track your career, and what all the data means. This section contains advice on how to make the most of your time to get the highest scores. Flight Dispatch -- documents how to select and plan a flight and have that flight be committed into your log. Profile and Settings (formerly “Options for All Airlines”) -- contains an explanation of the FSCap- tain settings that apply to your entire installation and not to a specific airline. This also explains how to configure FSCaptain for dual operations – sharing the same career in FS2004, FSX, and P3D. Configuring Aircraft -- will tell you how to create and maintain the aircraft overrides that help FS- Captain calculate the flight profiles for the different airplanes you fly. -

Eac Regional Transport Strategy March 2011

East African Community Secretariat THE EAST AFRICAN TRADE AND TRANSPORT FACILITATION PROJECT EAST AFRICAN TRANSPORT STRATEGY AND REGIONAL ROAD SECTOR DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM FINAL REPORT PART II: EAC REGIONAL TRANSPORT STRATEGY MARCH 2011 Prepared By: Africon Ltd EAC Transport Strategy and Regional Roads Sector Development Program STRUCTURE OF DOCUMENT This report is made up of four parts: Part I provides the general background to the study. It reports on the analyses that are common to and form the foundation of the Transport Strategy and Roads Development Program, including the regional corridors, the economy and demography of the region, transport demand and transport modelling, and the principles for project identification and prioritisation. Part II (this document) is the Transport Strategy. It covers the policy/institutional arrangements in the transport sector in the EAC and its member countries. It then provides an overview of regional issues and identifies regional interventions in each of the transport modes, i.e. roads, rail, ports, pipelines, airports and border posts. It concludes by presenting the prioritised interventions together with an implementation approach. Part III is the Roads Development Program. It covers the regional roads network, and analyses roads needs from capacity and condition perspectives. It also develops some cross-cutting themes (regional roads classification system, regional roads management system and regional overload control). Regional roads projects are identified and described. Part IV is the list of transport projects, together with short profiles for the priority projects. Parts II and III are drafted so that they can be read stand-alone, i.e. in isolation of the other three parts. -

1" OVERSIGHT of A(RPO'rt and AIRLINE Securily PROGRAMS

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. } ,. 1" OVERSIGHT OF A(RPO'RT AND AIRLINE SECURIlY PROGRAMS (99-21) HEARING BEFORE THE SUBOOMMITTEE ON AVlATION OF THE OOMMITTEE ON PUBLIO WORKS AND TRANSPORTATION HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES NINETY-NINTH CONGRESS FmST SESSION JULy 11, 1985 u.s. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1985 COMMI'ITEE ON PUBLIC WORKS AND TRANSPORTATION JAMES J. HOWARD, New Jersey, Chairman GLENN M. ANDERSON, California GENE SNYDER, Kentucky ROBERT A. ROE, New Jersey JOHN PAUL HAMMERSCHMIDT, Arkansas JOHN B. BREAUX, Louisiana BUD SHUSTER, Pennsylvania NORMAN Y. MINETA, California ARLAN STANGELAND, Minnesota JAMES L. OBERSTAR, Minnesota NEWT GINGRICH, Georgia HENRY J. NOWAK, New York WILLIAM F. CLINGER, JR., Pennsylvania ROBERT W. EDGAR, Pennsylvania GUY MOLINARI. New York ROBERT A. YOUNG, Missouri E. CLAY SHAW, JR., Florida NICK JOE RAHALL il, West Virginia BOB McEWEN, Ohio DOUGLAS APPLEGATE, Ohio THOMAS E. PETRI, Wisconsin RON DE LUGO, Virgin Islands DON SUNDQUIST, Tennessee GUS SAVAGE, lllinois NANCY L. JOHNSON. Connecticut FOFO I.F. SUNIA, American Samoa RON PACKARD. California DOUGLAS H. BOSCO, California SHERWOOD BOEHLERT, New York JIM MOODY, Wisconsin TOM DELAY, Texas ROBERT A. BORSKI, Pennsylvania SONNY CALLAHAN. Alabama JOE KOLTER, Pennsylvania DEAN A. GALLO, New Jersey TIM VALENTINE, North Carolina HELEN DELICH BENTLEY, Maryland EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York JIM LIGHTFOOT, Iowa WILLIAM O. LIPINSKI, lllinois DAVID S. MONSON, Utah MICHAEL A. ANDREWS, Texas J. ROY ROWLAND, Georgia ROBERT E. WISE, JR., West Virginia KENNETH J. GRAY, Illinois CHESTER G. ATKINS, Massachusetts PETER J. VISCLOSKY, Indiana JAMES A. TRAFICANT, JR., Ohio CATHY (MRS. -

AASP Mission, Goals, Measures, & Classifications

Mission, Goals, Measures and Classifications A COMPONENT OF THE November 2011 Prepared for With a Grant from Alaska Department Federal Aviation of Transportation and Administration Public Facilities Prepared by: As subconsultants to: WHPACIFIC, Inc. DOWL HKM 300 W. 31st Avenue 4041 B Street Anchorage, Alaska 99503 www.AlaskaASP.com Anchorage, Alaska 99503 907-339-6500 907-562-2000 A message from the Desk of Steven D. Hatter, Deputy Commissioner – Aviation I am pleased to present this report on the Mission, Goals, Performance Measures and Classifications of Alaska’s Airports. The goals, objectives, performance measures, and airport classifications presented herein establish a framework to set priorities and guide our work in aviation. They also provide mechanisms to help implement the aviation-related goals and priorities identified in the Alaska Statewide Transportation Policy Plan (“Let’s Get Moving 2030”) and the Department’s 2011 Strategic Agenda. The development of a relevant and integrated system of goals, objectives, and performance measures provides the Department with a powerful tool for communicating with the public and legislators, managing resources, and motivating employees. Our goals are general guidelines that explain what is to be achieved by the Department’s aviation programs. Our objectives define the specific strategies or implementation steps we will take to attain the goals – the “who, what, when, where, and how” of reaching the goals. Our performance measures provide statistical evidence to indicate whether progress is being made towards our objectives. Performance measures are an essential tool in public administration, used to direct resources and ensure that programs are producing intended results. Alaska has over 700 registered airports and these airports vary widely in size, use, and the amount of infrastructure and facility development. -

APPENDIX H Inventory and Database Documentation

APPENDIX H Inventory and Database Documentation • Inventory Database, Classifications and Performance Measures Framework Technical Memorandum • Inventory Database Preparation Statement of Services - from AASP NTP3 Technical Memorandum – Task 5 Inventory, Database, Classifications, and Performance Measures Framework WHPacific May 7, 2008 Context: This technical memorandum is one of six produced for Phase I, Stage 1 of the Alaska Aviation system Plan (AASP). Phase I, Stage 1 comprises a three to four month period of preparatory tasks for the AASP. The scope of this technical memorandum is to provide a 10- to 20-page review of the available and needed inventory for the AASP, particularly as it relates to individual airports and performance measures.1 The inventory and database development will be completed in Phase 2. The type of information collected for the inventory and database depends on airport classifications and performance measures, so the prior AASPs and a sampling of other states’ classifications and performance measures are presented. In the appendix to this technical memorandum is a listing of existing available databases, with detailed descriptions of five. This technical memorandum will help ensure that the inventory performed in Stage 2 of Phase I is important information to know in order to improve the Alaska aviation system. Introduction: An almost infinite amount of information relevant to the Alaska aviation system could be collected. For an aviation system plan, however, it is most important to collect and analyze information that helps to assess the condition and performance of the system. The purpose of this technical memorandum is to review options and make recommendations regarding later inventory and performance measurement tasks for the AASP. -

Aviation Security, Privacy, Data Protection and Other Human Rights: Technologies and Legal Principles Law, Governance and Technology Series

Law, Governance and Technology Series Sub-series: Issues in Privacy and Data Protection 37 Olga Mironenko Enerstvedt Aviation Security, Privacy, Data Protection and Other Human Rights: Technologies and Legal Principles Law, Governance and Technology Series Issues in Privacy and Data Protection Volume 37 Series editors Pompeu Casanovas, Barcelona, Spain Giovanni Sartor, Florence, Italy Serge Gutwirth, Brussels, Belgium Issues in Privacy and Data Protection aims at publishing peer reviewed scientific manuscripts that focus upon issues that engage into an analysis or reflexion related to the consequences of scientific and technological developments upon the private sphere, the personal autonomy and the self-construction of humans with data pro- tection and privacy as anchor points. The objective is to publish both disciplinary, multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary works on questions that relate to experiences and phenomena that can or could be covered by legal concepts stemming from the law regarding the protection of privacy and/or the processing of personal data. Since both the development of science and technology, and in particular information tech- nology (ambient intelligence, robotics, artificial intelligence, knowledge discovery, data mining, surveillance, etc.), and the law on privacy and data protection are in constant frenetic mood of change (as is clear from the many legal conflicts and reforms at hand), we have the ambition to reassemble a series of highly contempo- rary and forward-looking books, wherein cutting edge issues