TIKKUN on Shavuot - the Deeper Meaning Rabbi Scott N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Covenant Renewal Ceremony As the Main Function of Qumran

religions Article The Covenant Renewal Ceremony as the Main Function of Qumran Daniel Vainstub Department of Bible, Archaeology and Ancient Near East, Ben‑Gurion University, Beer Sheva 8410501, Israel; [email protected] Abstract: Unlike any other group or philosophy in ancient Judaism, the yahad sect obliged all mem‑ ˙ bers of the sect to leave their places of residence all over the country and gather in the sect’s central site to participate in a special annual ceremony of renewal of the covenant between God and each of the members. The increase of the communities that composed the sect and their spread over the en‑ tire country during the first century BCE required the development of the appropriate infrastructure for hosting this annual gathering at Qumran. Consequently, the hosting of the gathering became the main function of the site, and the southern esplanade with the buildings surrounding it became the epicenter of the site. Keywords: Qumran; Damascus Document; scrolls; mikveh 1. Introduction The subject of this paper is the yearly gathering during the festival of Shavuot of all members of the communities that composed the yahad sect.1 After close examination of the Citation: Vainstub, Daniel. 2021. The ˙ evidence for this annual gathering in the sect’s writings and analysis of the archaeological Covenant Renewal Ceremony as the data on the development of the site of Qumran, it became evident that in the generation Main Function of Qumran. Religions 12: 578. https://doi.org/10.3390/ following that of the site’s founders, the holding of the annual gathering became the main ¶ rel12080578 raison d’ tre of the site and the factor that dictated its architectural development. -

A New Essenism: Heinrich Graetz and Mysticism

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Faculty Scholarship 1998 A New Essenism: Heinrich Graetz and Mysticism Jonathan Elukin Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/facpub Part of the History Commons Copyright © 1998 The Journal of the History of Ideas, Inc.. All rights reserved. Journal of the History of Ideas 59.1 (1998) 135-148 A New Essenism: Heinrich Graetz and Mysticism Jonathan M. Elukin Since the Reformation, European Christians have sought to understand the origins of Christianity by studying the world of Second Temple Judaism. These efforts created a fund of scholarly knowledge of ancient Judaism, but they labored under deep-seated pre judices about the nature of Judaism. When Jewish scholars in nineteenth-century Europe, primarily in Germany, came to study their own history as part of the Wissenschaft des Judentums movement, they too looked to the ancient Jewish past as a crucia l element in understanding Jewish history. A central figure in the Wissenschaft movement was Heinrich Graetz (1817-1891). 1 In his massive history of the Jews, the dominant synthesis of Jewish history until well into the twentieth century, Graetz constructed a narrative of Jewish history that imbedded mysticism deep within the Jewish past, finding its origins in the first-cen tury sectarian Essenes. 2 Anchoring mysticism among the Essenes was crucial for Graetz's larger narrative of the history of Judaism, which he saw as a continuing struggle between the corrosive effects of mysticism [End Page 135] and the rational rabbinic tradition. An unchanging mysticism was a mirror image of the unchanging monotheistic essence of normative Judaism that dominated Graetz's understanding of Jewish history. -

Norman Golb 7 December 2011 Oriental Institute, University of Chicago

This article examines a series of false, erroneous, and misleading statements in Dead Sea Scroll museum exhibits. The misinformation can be broken down into four basic areas: (1) erroneous claims concerning Judaism and Jewish history; (2) speculative, arbitrary and inaccurate claims about the presumed “Essenes” of Qumran; (3) misleading claims concerning Christian origins; and (4) religiously slanted rhetoric concerning the “true Israel” and the “Holy Land.” The author argues that the statements, viewed in their totality, raise serious concerns regarding the manner in which the Scrolls are being presented to the public. Norman Golb 7 December 2011 Oriental Institute, University of Chicago RECENT SCROLL EXHIBITS AND THE DECLINE OF QUMRANOLOGY While significant advances have been made in Dead Sea Scrolls research over the past decade, defenders of the traditional “Qumran-sectarian” theory continue to use various publicity tools to push their agenda. These tools include, for example, the recent media campaign surrounding the claim that textiles found in the caves near Qumran “may” demonstrate that the site was inhabited by Essenes — a sensationalist argument that misleads the public with a mix of speculation and presuppositions.1 The tools have also included museum exhibits where efforts, either overt or subtle, are made to convince the public that the traditional theory is still viable. If we focus merely on the museums, we find that a noteworthy aspect of the exhibits involves the dissemination of certain erroneous and misleading facts concerning Jewish history and Christian origins. I here discuss some of the more obvious distortions, quoting from various exhibits of the past two decades. -

Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature

i “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Nathaniel Deutsch Professor Juana María Rodríguez Summer 2016 ii “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature Copyright © 2016 by Anna Elena Torres 1 Abstract “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature examines the intertwined worlds of Yiddish modernist writing and anarchist politics and culture. Bringing together original historical research on the radical press and close readings of Yiddish avant-garde poetry by Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, Peretz Markish, Yankev Glatshteyn, and others, I show that the development of anarchist modernism was both a transnational literary trend and a complex worldview. My research draws from hitherto unread material in international archives to document the world of the Yiddish anarchist press and assess the scope of its literary influence. The dissertation’s theoretical framework is informed by diaspora studies, gender studies, and translation theory, to which I introduce anarchist diasporism as a new term. -

Judaism: Pharisees, Scribes, Sadducees, Essenes, and Zealots Extremist Fighters Who Extremist Political Freedom Regarded Imperative

Judaism: Pharisees,Scribes,Sadducees,Essenes,andZealots © InformationLtd. DiagramVisual PHARISEES SCRIBES SADDUCEES ESSENES ZEALOTS (from Greek for “separated (soferim in ancient Hebrew) (perhaps from Greek for (probably Greek from the (from Greek “zealous one”) ones”) “followers of Zadok,” Syriac “holy ones”) Solomon’s High Priest) Evolution Evolution Evolution Evolution Evolution • Brotherhoods devoted to • Copiers and interpreters • Conservative, wealthy, and • Breakaway desert monastic • Extremist fighters who the Torah and its strict of the Torah since before aristocratic party of the group, especially at regarded political freedom adherence from c150 BCE. the Exile of 586 BCE. status quo from c150 BCE. Qumran on the Dead Sea as a religious imperative. Became the people’s party, Linked to the Pharisees, Usually held the high from c130 BCE Underground resistance favored passive resistance but some were also priesthood and were the Lived communally, without movement, especially to Greco-Roman rule Sadducees and on the majority of the 71-member private property, as farmers strong in Galilee. The Sanhedrin Supreme Sanhedrin Supreme or craftsmen under a most fanatical became Council Council. Prepared to work Teacher of Righteousness sicarii, dagger-wielding with Rome and Herods and Council assassins Beliefs Beliefs Beliefs Beliefs Beliefs • Believed in Messianic • Defined work, etc, so as • Did not believe in • Priesthood, Temple • “No rule but the Law – redemption, resurrection, to keep the Sabbath. resurrection, free will, sacrifices, and calendar No King but God”. They free will, angels and Obedience to their written angels, and demons, or were all invalid. They expected a Messiah to demons, and oral code would win salvation oral interpretations of the expected the world’s early save their cause interpretations of the Torah – enjoy this life end and did not believe in Torah resurrection. -

Sadducees, Pharisees, and the Controversy of Counting the Omer by J.K

Sadducees, Pharisees, and the Controversy of Counting the Omer by J.K. McKee posted 17 January, 2008 www.tnnonline.net The season between Passover and Unleavened Bread, and the Feast of Weeks or Shavuot, is one of the most difficult times for the Messianic community. While this is supposed to be a very special and sacred time, a great number of debates certainly rage over Passover. Some of the most obvious debates among Messianics occur over the differences between Ashkenazic and Sephardic Jewish halachah. Do we eat lamb or chicken during the sedar meal? What grains are “kosher for Passover”? Can egg matzos be eaten? What are we to have on our sedar plate? What traditions do we implement, and what traditions do we leave aside? And, what do we do with the uncircumcised in our midst? Over the past several years, I have increasingly found myself taking the minority position on a number of issues. Ironically, that minority position is usually the traditional view of mainline American, Ashkenazic Conservative and/or Reform Judaism—the same halachah that I was originally presented with when my family entered into Messianic Judaism in 1995. I have found myself usually thrust among those who follow a style halachah that often deviates from the mainstream. Certainly, I believe that our Heavenly Father does allow for creativity when it comes to human traditions. Tradition is intended to bind a religious and ethnic community together, giving it cohesion and a clear connection to the past. It is only natural for someone like myself, of Northern European ancestry, to more closely identify with a Northern and Central European style of Judaism, than one from the Mediterranean. -

A Brief History of Tikkun Leil Shavuot Rabbi Dr

A Brief History of Tikkun Leil Shavuot Rabbi Dr. Andrew Schein Senior lecturer, Netanya Academic College • ’88 RIETS One of the popular customs on Shavuot is to stay awake all night learning Torah. This custom is not mentioned in the Mishnah, the Gemara, by the Gaonim, the Rambam, the Tur, in the Shulchan Arukh (though see below) and by the Rama. What is the basis for this custom and how did it develop? The oldest source for this custom is from Philo who mentions that the Essenes (1st century) used to stay awake the night of Shavuot praying.57 However, it is unlikely that their practice had any influence on our present custom since the Essenes were not part of mainstream Judaism, and this source is never referred to again. The next mention of this custom is in the Zohar (on Vayikra 23), which records that a select group of people, Hasidim, used to stay awake the night of Shavuot learning Torah in order that the bride (the Shekhinah? the Jewish people?) would be adorned appropriately to meet the King (G-d) in the morning. In Spain, in the 14th and 15th centuries it is possible that there were some individuals who stayed awake all night on Shavuot, but it was definitely not a common practice.58 R. David Abudraham (Spain, late 13th, early 14th century) in his book on prayers and customs, makes no mention of the custom even though he records in detail the prayers and customs of Shavuot. In the 16th century there was a new stage in the development of the custom. -

The Eschatology of the Dead Sea Scrolls

Eruditio Ardescens The Journal of Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary Volume 2 Issue 2 Article 1 February 2016 The Eschatology of the Dead Sea Scrolls J. Randall Price Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/jlbts Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Price, J. Randall (2016) "The Eschatology of the Dead Sea Scrolls," Eruditio Ardescens: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/jlbts/vol2/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eruditio Ardescens by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Eschatology of the Dead Sea Scrolls J. Randall Price, Ph.D. Center for Judaic Studies Liberty University [email protected] Recent unrest in the Middle East regularly stimulates discussion on the eschatological interpretation of events within the biblical context. In light of this interest it is relevant to consider the oldest eschatological interpretation of biblical texts that had their origin in the Middle East – the Dead Sea Scrolls. This collection of some 1,000 and more documents that were recovered from caves along the northwestern shores of the Dead Sea in Israel, has become for scholars of both the Old and New Testaments a window into Jewish interpretation in the Late Second Temple period, a time known for intense messianic expectation. The sectarian documents (non-biblical texts authored by the Qumran Sect or collected by the Jewish Community) among these documents are eschatological in nature and afford the earliest and most complete perspective into the thinking of at least one Jewish group at the time of Jesus’ birth and the formation of the early church. -

Sacrificial Cult at Qumran? an Evaluation of the Evidence in the Context of Other Alternate Jewish Practices in the Late Second Temple Period

SACRIFICIAL CULT AT QUMRAN? AN EVALUATION OF THE EVIDENCE IN THE CONTEXT OF OTHER ALTERNATE JEWISH PRACTICES IN THE LATE SECOND TEMPLE PERIOD Claudia E. Epley A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Classics Department in the College of Arts & Sciences. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Donald C. Haggis Jennifer E. Gates-Foster Hérica N. Valladares © 2020 Claudia E. Epley ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Claudia E. Epley: Sacrificial Cult at Qumran? An Evaluation of the Evidence in the Context of Other Alternate JeWish Practices in the Late Second Temple Period (Under the direction of Donald C. Haggis) This thesis reexamines the evidence for JeWish sacrificial cult at the site of Khirbet Qumran, the site of the Dead Sea Scrolls, in the first centuries BCE and CE. The interpretation of the animal remains discovered at the site during the excavations conducted by Roland de Vaux and subsequent projects has long been that these bones are refuse from the “pure” meals eaten by the sect, as documented in various documents among the Dead Sea Scrolls. However, recent scholarship has revisited the possibility that the sect residing at Qumran conducted their own animal sacrifices separate from the Jerusalem temple. This thesis argues for the likelihood of a sacrificial cult at Qumran as evidenced by the animal remains, comparable sacrificial practices throughout the Mediterranean, contemporary literary Works, and the existence of the JeWish temple at Leontopolis in lower Egypt that existed at the same time that the sect resided at Qumran. -

Pharisees, Sadducees, and Essenes

Pharisees, Sadducees, and Essenes Characteristic Pharisees Sadducees Essenes (a) Hebrew word meaning “separate”; (a) Hebrew word tsadiq, meaning Possibly derived from an Aramaic Possible Origin of Name or (b) Hebrew word meaning “holy”; or (b) the name “Zadok”, the word for “pious”. “specifier”. Aaronic priest who anointed Solomon, which led to the Jewish desire that the High Priest be of the family of Zadok. Around 150 - 140 BC during the Around 150 - 140 BC during the Around 170 or 160 BC, founded by an Timeframe When Sect Appears Hasmonean dynasty. Hasmonean dynasty. (Same enigmatic figure called the “Teacher of timeframe as Pharisees.) Righteousness”. Pharisees were common people, but Sadducees advocated an ironclad link Their isolationist lifestyle precluded an knowledgeable. Taught in the between Judaism and the temple. active role in then-contemporary synagogues and interpreted the Torah They oversee the sacrifices and Judaism. They very likely copied and Role in Judaism and the oral traditions. Well-liked by maintenance of the temple. During preserved scrolls that were deemed the common people. Advocated for most of the intertestamental period scripture; as well as scrolls that social justice. they make up the majority of the defined the rules that governed their By the first century AD, Pharisees Sanhedrin. High Priest is usually a lifestyle and beliefs. became mired in the minutia and letter Sadducee. Minimal intermingling with outsiders. of Mosaic Law, rather than its intent. - Strict adherence to the Torah; oral - Ritual purity. - Oral law and traditions were sacred teachings were noted but not sacred. - Hierarchical system of angels. along with the Torah. -

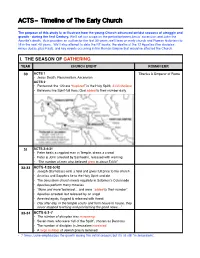

WBW | P.2 | Timeline of Acts | Notes

ACTS- Timeline of The Early Church The purpose of this study is to illustrate how the young Church advanced amidst seasons of struggle and growth - during the first Century. We’ll set our scope on the period between Jesus’ ascension and John the Apostle’s death. Acts provides an outline for the first 30 years; we’ll lean on early church and Roman historians to fill in the next 40 years. We’ll also attempt to date the NT books, the deaths of the 12 Apostles (the disciples minus Judas, plus Paul), and key events occurring in the Roman Empire that would’ve affected the Church. I. THE SEASON OF GATHERING YEAR CHURCH EVENT ROMAN EMP. 30 ACTS 1 Tiberius is Emperor of Rome • Jesus Death, Resurrection, Ascension ACTS 2 • Pentecost: the 120 are “baptized” in the Holy Spirit; 3,000 believe • Believers live Spirit-full lives; God added to their number daily 31 ACTS 3-4:31 • Peter heals a crippled man in Temple, draws a crowd • Peter & John arrested by Sanhedrin, released with warning • “The number of men who believed grew to about 5,000” 32-33 ACTS 4:32-5:42 • Joseph (Barnabas) sells a field and gives full price to the church • Ananias and Sapphira lie to the Holy Spirit and die • The Jerusalem church meets regularly in Solomon’s Colonnade • Apostles perform many miracles • “More and more” believed… and were “added to their number” • Apostles arrested, but released by an angel • Arrested again, flogged & released with threat • Day after day, in the temple courts and from house to house, they never stopped teaching and proclaiming the good news…” 33-34 ACTS 6:1-7 • The number of disciples was increasing • Seven men, who were “full of the Spirit”, chosen as Deacons • The number of disciples in Jerusalem increased • A large number of Jewish priests believed • 7 times, Luke emphasizes the growth during this initial season; but it’s all still “in Jerusalem”. -

When Does Counting the Omer Begin? After the Shabbat” (Leviticus 23:15)

When Does Counting the Omer Begin? after the Shabbat” (Leviticus 23:15). Jewish“ ,ממחרת השבת The omer or “sheaf” offering takes place interpreters have debated the exact meaning of this phrase for two millennia, resulting in all four possible dates being adopted by one Jewish sect or another. Prof. Marvin A. Sweeney , Dr. Rabbi Zev Farber A Sefirat ha-Omer booklet (“Counting of the Omer”) c. 1800 Zürich, Braginsky Collection, B327, f. 50 The Omer Offering of First Sheaf ollowing its description of the laws of the Matzot festival, Leviticus 23 describes the requirement to bring the omer :sheaf”), the first cut of grain, to the priest“ ,עומר) F Lev 23:10 …When you enter the land that I am giving to you and you ויקרא כג:י …ִכּי ָתבֹאוּ ֶאל ָהָאֶרץ ֲאֶשׁר ֲא ִני ֹנֵתן ָלֶכם ַ וְּקצְרֶתּם reap its harvest, you shall bring the first sheaf of your harvest to the ֶאת ְקִציָרהּ ַוֲהֵבאֶתם ֶאת עֶֹמר ֵראִשׁית ְקִציְרֶכם ֶאל ַהכֵֹּהן. priest. 23:11 He shall elevate the sheaf before YHWH for acceptance in כג:יאְוֵהִניף ֶאת ָהעֶֹמר ִלְפֵני ְי-הָוה ִלְרצְֹנֶכם ִמָמֳּחַרת ַהַשָּׁבּת .your behalf; the priest shall elevate it on the day after the shabbat ְיִניֶפנּוּ ַהכֵֹּהן. Unlike the Pesach offering and Matzot Festival, no exact date is given for this omer offering, only that it happens after the shabbat when the harvest is first reaped.[1] Establishing the correct date of the omer offering was especially important since the date for the Bikkurim festival (also called Shavuot) is determined by it: Lev 23:15 And from the day on which you bring the sheaf of elevation ויקרא כג טו וְּסַפְרֶתּם ָלֶכם ִמָמֳּחַרת ַהַשָּׁבּת ִמיּוֹם ֲהִביֲאֶכם ֶאת .offering– the day after the sabbath — you shall count off seven weeks עֶֹמר ַהְתּנוָּפה ֶשַׁבע ַשָׁבּתוֹת ְתּ ִמיֹמת ִתְּהֶייָנה.