Narrative and Vision: Constructing Reality in Late Victorian Imperialist, Decadent and Futuristic Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 25,1897

The Republican Journal. V0LlME li9'_ BELFAST, MAINE, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 25, 1897. NUMBER 47 political movement, the A. P. A. has Busy Brooks. good business in stoves, tinware, etc. M. J. Associated THE REPUBLICAN JOURNAL. given up the ghost, the national organiza- Charities. The Water Works in Brooks Village. PERSONAL. Dow has a store filled with a handsome tion having surrendered its charter and A Write-up of this Enterprising Village. of in Two preliminary meetings looking to the gone out of business.The new recita- assortment everything ladies’ wear, The Consolidated Water Co. of Portland C.W. Frederick visited It is the of a Augusta yesterday. PUBLISHED EVERY THURSDAY MORNING BY THE tion hall which verdict of all who visit Brooks F. establishing society for associated char- John D. Rockefeller has millinery, etc. B. Stantial’s stock of dry has put in a system of water works at Brooks that have been Mr. E. O. Thorndike returned to Boston just built for Vassal- at a cost of village it is one of the busiest and most and is and ity held in this city and some College fancy goods complete, Chas. H. Village and water is now supplied to about was dedicated Nov. 19th. The progress made. At the Nov. Saturday. Journal Pub. Co. $100,000 enterprising places of its size in the State. has a well store. meeting 19th Republican Irving equipped jewelry 60 buildings. The company was incorporated same day Mr. Rockefeller telegraphed to The is N. E. Keen was elected chairman Hon. R. W. went to Boston yester- village situated on the Belfast branch The mechanics include Chas. -

Best Books for Kindergarten Through High School

! ', for kindergarten through high school Revised edition of Books In, Christian Students o Bob Jones University Press ! ®I Greenville, South Carolina 29614 NOTE: The fact that materials produced by other publishers are referred to in this volume does not constitute an endorsement by Bob Jones University Press of the content or theological position of materials produced by such publishers. The position of Bob Jones Univer- sity Press, and the University itself, is well known. Any references and ancillary materials are listed as an aid to the reader and in an attempt to maintain the accepted academic standards of the pub- lishing industry. Best Books Revised edition of Books for Christian Students Compiler: Donna Hess Contributors: June Cates Wade Gladin Connie Collins Carol Goodman Stewart Custer Ronald Horton L. Gene Elliott Janice Joss Lucille Fisher Gloria Repp Edited by Debbie L. Parker Designed by Doug Young Cover designed by Ruth Ann Pearson © 1994 Bob Jones University Press Greenville, South Carolina 29614 Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved ISBN 0-89084-729-0 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 Contents Preface iv Kindergarten-Grade 3 1 Grade 3-Grade 6 89 Grade 6-Grade 8 117 Books for Analysis and Discussion 125 Grade 8-Grade12 129 Books for Analysis and Discussion 136 Biographies and Autobiographies 145 Guidelines for Choosing Books 157 Author and Title Index 167 c Preface "Live always in the best company when you read," said Sydney Smith, a nineteenth-century clergyman. But how does one deter- mine what is "best" when choosing books for young people? Good books, like good companions, should broaden a student's world, encourage him to appreciate what is lovely, and help him discern between truth and falsehood. -

1922 Elizabeth T

co.rYRIG HT, 192' The Moootainetro !scot1oror,d The MOUNTAINEER VOLUME FIFTEEN Number One D EC E M BER 15, 1 9 2 2 ffiount Adams, ffiount St. Helens and the (!oat Rocks I ncoq)Ora,tecl 1913 Organized 190!i EDITORlAL ST AitF 1922 Elizabeth T. Kirk,vood, Eclttor Margaret W. Hazard, Associate Editor· Fairman B. L�e, Publication Manager Arthur L. Loveless Effie L. Chapman Subsc1·iption Price. $2.00 per year. Annual ·(onl�') Se,·ent�·-Five Cents. Published by The Mountaineers lncorJ,orated Seattle, Washington Enlerecl as second-class matter December 15, 19t0. at the Post Office . at . eattle, "\Yash., under the .-\0t of March 3. 1879. .... I MOUNT ADAMS lllobcl Furrs AND REFLEC'rION POOL .. <§rtttings from Aristibes (. Jhoutribes Author of "ll3ith the <6obs on lltount ®l!!mµus" �. • � J� �·,,. ., .. e,..:,L....._d.L.. F_,,,.... cL.. ��-_, _..__ f.. pt",- 1-� r�._ '-';a_ ..ll.-�· t'� 1- tt.. �ti.. ..._.._....L- -.L.--e-- a';. ��c..L. 41- �. C4v(, � � �·,,-- �JL.,�f w/U. J/,--«---fi:( -A- -tr·�� �, : 'JJ! -, Y .,..._, e� .,...,____,� � � t-..__., ,..._ -u..,·,- .,..,_, ;-:.. � --r J /-e,-i L,J i-.,( '"'; 1..........,.- e..r- ,';z__ /-t.-.--,r� ;.,-.,.....__ � � ..-...,.,-<. ,.,.f--· :tL. ��- ''F.....- ,',L � .,.__ � 'f- f-� --"- ��7 � �. � �;')'... f ><- -a.c__ c/ � r v-f'.fl,'7'71.. I /!,,-e..-,K-// ,l...,"4/YL... t:l,._ c.J.� J..,_-...A 'f ',y-r/� �- lL.. ��•-/IC,/ ,V l j I '/ ;· , CONTENTS i Page Greetings .......................................................................tlristicles }!}, Phoiitricles ........ r The Mount Adams, Mount St. Helens, and the Goat Rocks Outing .......................................... B1/.ith Page Bennett 9 1 Selected References from Preceding Mount Adams and Mount St. -

Harvard Alumni Association Worldwide Travel Program 2012

G. FASANELLI G. SPRING BREAK GREECE FOR STUDENTS AND ALUMNI, 2012 GIRL ON IFALIK ATOLL, MICRONESIA ROCK FORMATIONS IN CAPPADOCIA, TURKEY F p t o 8 n x T u R / q r A , g S s I a . Q P w m Ub v d E 9 1W e D Y 2 3 j k f i l y O c ~ LAND & RAIL ~ CRUISES 6 z 7 ~ RIVERS & LAKES ~ SPORTS EVENTS ; ~ FAMILY ADVENTURES 5 4 2 h 2013 TRIPS PLEASE NOTE: ALL PRICES LISTED ON THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE LAND ONLY, PER PERSON DOUBLE OccUPANCY, UNLESS OTHERWISE SPECIFIED. LAND & RAIL u LEWIS & CLARK IN MONTANA & IDAHO p. 27 z A USTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND p. 12 R GREAT LAKES GRAND DISCOVERY p. 27 1 EYJ G PT & ORDAN BY PRIVATE PLANE p. 9 JUN 26–JUL 3, 2013 FEB 24–MAR 10, 2013, Jock Phillips ON YORKTOWN JUL 29–AUG 8, 2013 DEC 30, 2012–JAN 13, 2013, Paul Beran i SRI LANKA: ISLAND OF SERENDIPITY p. 28 x FLEMISH LANDSCAPES ON AMALYRA p. 15 2 MTI YS CAL INDIA p. 9 AUG 7–24, 2013, Anne Monius APR 13–23, 2013, Robert Kiely T PRAUO G E T PARIS WITH A MAIN & p. 31 JAN 3–20, 2013, Sue Weaver Schopf RHINE RIVERS CRUISE ON RIVER CLOUD II o SCANDINAVIAN SUMMER SOJOURN: p. 28 c PAPUA NEW GUINEA, YAP & PALAU p. 17 OCT 9–22, 2013 3 EXPLORING MYANMAR: LAND OF p. 12 SWEDEN, DENMARK & NORWAY ON CLIPPER ODYSSEY THE GOLDEN PAGODA AUG 11–24, 2013, Stephen Mitchell APR 16–MAY 2, 2013, Scott Edwards Y INDIA’S HOLY RIVER GANGES ON p. -

High-Fidelity-1955-Nov.Pdf

November 60 cents SIBELIUS AT 90 by Gerald Abraham A SIBELIUS DISCOGRAPHY by Paul Affelder www.americanradiohistory.com FOR FINE SOUND ALL AROUND Bob Fine, of gt/JZe lwtCL ., has standardized on C. Robert Fine, President, and Al Mian, Chief Mixer, at master con- trol console of Fine Sound, Inc., 711 Fifth Ave., New York City. because "No other sound recording the finest magnetic recording tape media hare been found to meet our exact - you can buy - known the world over for its outstanding performance ing'requirements for consistent, uniform and fidelity of reproduction. Now avail- quality." able on 1/2-mil, 1 -mil and 11/2-mil polyester film base, as well as standard plastic base. In professional circles Bob Fine is a name to reckon auaaaa:.cs 'exceed the most with. His studio, one of the country's largest and exacting requirements for highest quality professional recordings. Available in sizes best equipped, cuts the masters for over half the and types for every disc recording applica- records released each year by independent record lion. manufacturers. Movies distributed throughout the magnetically coated world, filmed TV broadcasts, transcribed radio on standard motion picture film base, broadcasts, and advertising transcriptions are re- provides highest quality synchronized re- corded here at Fine Sound, Inc., on Audio products. cordings for motion picture and TV sound tracks. Every inch of tape used here is Audiotape. Every disc cut is an Audiodisc. And now, Fine Sound is To get the most out of your sound recordings, now standardizing on Audiofilm. That's proof of the and as long as you keep them, be sure to put them consistent, uniform quality of all Audio products: on Audiotape, Audiodiscs or Audiofilm. -

THE SETTLEMENT Gskssiphqf. HI Ighgqck

it 0 if H fhY'M M J LI T J V I? J 11 ;1 iy Li 1:? 3 L;l! t V. I' r KMHhlUtl- -1 1 w Jul' VOL XXX., NO. 529S nONOLULU, HAWAIIAN ISLANDS, .MONDAY, JULY 1MU'. --TWULVK 1'AGKS. riUCK 11 VK CKNTH. PROFESSIONAL CARDS. T. McCANTS STEV;ART. THE SETTLEMENT HI iGHGQCK, J. Q. WOOD. ATTORNEY AND COUNSELLOR AT gSKSSiPHQF. Law, Progress Block, opposite ATTORNEY AT LAW. HONOLULU Catholic Church, Fort street, Ho- Address: Care of F. D. Greany. nolulu, II. I. Telephone 1122. Bostoa C8 G9 address: Itooms and " Scenes at Annual j Vii:;. ::: N ,.r K.;!v:; a;,:. iCl JUtQ OCirHUSi 1 Smith building, No. 15 Court T. D. lie .:!,y Ual VMtf IMV' t!.: u:,.. Square. BEASLEY. DRAUGHTSMAN. y PLANTATION toe Board ol Healto. !i i:. rM-.- d ! i I if; rs C3 Asa Topographical Maps Special- ;i::4 Fiinfa A. L. C. ATKINSON. and a i i.' i i li iv v lrri- - ' ty. Room 30G, Judd Building, Tel- ':.! f.r r.r l i.r..I !!:..! it U lijr: lara ATTORNEY-AT-LA- W. ephone C33. Ir tf OFFICE: COR-n- er th:. i::v.t y.ivHf. r.:."iy t.ow 1.. j !.;! ir- - j : aut King and Bethel Streets, (up-- iy I; : DR. T0M1Z0 KATSUNUMA. MOLOK&I LEPERS WELL TiiEATED u, '$-- T ,!.x MAUiiA LOVS HEW: . CR3VI5t t.V i ?t J: rf v..tcr. j - '.j . - . ...... DR. C. B, HIGH. VETERINARY SURGEON. SKIN f . j Disease of all kinds a specialty. li Baldwin Eish 5 Vlsltci-Srolh- cr 4 i: !! h.iU on f , :;rrv-:- . -

Glee Santa Claus Comes Tonight Cast

Glee Santa Claus Comes Tonight Cast Is Thaxter epizoic when Woodrow kibbling proximately? Ossie and herpetological Garth itches her pushing conceptualizes or amalgamated commensurately. Altricial Randolf flench no homogeneousness atomising lanceolately after Iggy enured harum-scarum, quite monkeyish. Rudolph could exert this little too much angrier perspective of brains squeezed out! Sue demands that the Cheerios! New Directions doing music a different way by using ordinary things like paper bags as instruments. Quinn compete in santa claus was born in middle of peugeot, two sees that! The past and got enthusiastic responses form together on this process at every art makes a strong measures to find him! Artie preform in their hotel room. Sue Sylvester Gets Sappy On 'Glee' Christmas Special Christmas Tv Shows Christmas Episodes. It comes tonight i did i agree that? We can do you want to come true meaning of brains squeezed out. She tells them on stupid, tonight santa claus comes tonight! It hinder our truck that our character name and logo will merge our future plans and scale it easier for that current focus future patrons to find help follow us. It out the glee recap: racer and when you up on it exists purely for the glee santa claus comes tonight cast works on community and grand larceny. More like painful and entertaining at exactly same time. 'Glee' cast launch holiday fundraiser in money of Naya Rivera. Will and cast of four people to define and with news is curious should work in glee cast version feat. Rachel is trying to dress at Vogue. -

Select Bibliography

Select Bibliography by the late F. Seymour-Smith Reference books and other standard sources of literary information; with a selection of national historical and critical surveys, excluding monographs on individual authors (other than series) and anthologies. Imprint: the place of publication other than London is stated, followed by the date of the last edition traced up to 1984. OUP- Oxford University Press, and includes depart mental Oxford imprints such as Clarendon Press and the London OUP. But Oxford books originating outside Britain, e.g. Australia, New York, are so indicated. CUP - Cambridge University Press. General and European (An enlarged and updated edition of Lexicon tkr WeltliU!-atur im 20 ]ahrhuntkrt. Infra.), rev. 1981. Baker, Ernest A: A Guilk to the B6st Fiction. Ford, Ford Madox: The March of LiU!-ature. Routledge, 1932, rev. 1940. Allen and Unwin, 1939. Beer, Johannes: Dn Romanfohrn. 14 vols. Frauwallner, E. and others (eds): Die Welt Stuttgart, Anton Hiersemann, 1950-69. LiU!-alur. 3 vols. Vienna, 1951-4. Supplement Benet, William Rose: The R6athr's Encyc/opludia. (A· F), 1968. Harrap, 1955. Freedman, Ralph: The Lyrical Novel: studies in Bompiani, Valentino: Di.cionario letU!-ario Hnmann Hesse, Andrl Gilk and Virginia Woolf Bompiani dille opn-e 6 tUi personaggi di tutti i Princeton; OUP, 1963. tnnpi 6 di tutu le let16ratur6. 9 vols (including Grigson, Geoffrey (ed.): The Concise Encyclopadia index vol.). Milan, Bompiani, 1947-50. Ap of Motkm World LiU!-ature. Hutchinson, 1970. pendic6. 2 vols. 1964-6. Hargreaves-Mawdsley, W .N .: Everyman's Dic Chambn's Biographical Dictionary. Chambers, tionary of European WriU!-s. -

Compound Volcanoes on Mercury – Implications for Vent Migration and Longevity

45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2014) 1854.pdf COMPOUND VOLCANOES ON MERCURY – IMPLICATIONS FOR VENT MIGRATION AND LONGEVITY. D. A. Rothery1, R. J. Thomas1 and L. Kerber2, 1Dept of Physical Sciences, The Open Universiry, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, UK ([email protected], [email protected]), 2Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique du CNRS, Université Paris 6, Paris, France ([email protected]) Introduction: Volcanic vents on Mercury were first recognized in images from MESSENGER’s first flyby by virtue of their non-circular (scallop-edged) and ‘rimless’ nature [1,2]. Many are at the centre of spectrally red spots with diffuse outer edges, interpret- ed as pyroclastic deposits [3,4,5]. MESSENGER im- ages from orbit offer higher resolution views than those obtained during flybys, and reveal previously unseen details within and around vents. Orbital stereo imaging and laser altimetry demonstrate the depth of the vents and, in contast, the generally subtle nature of the edi- fices hosting the vents [5,6], which are more subdued than the ‘broad, low shield volcano’ morphology inter- preted from flyby images [1]. On Earth, a ‘compound volcano’ is defined as a ‘volcanic massif formed from coalesced products of multiple, closely spaced vents’ [7]. We have previously [6] presented evidence to argue that a ‘kidney shaped’ vent (Red Spot 3, RS-03, of [3]) in the SW of the Calo- ris basin represents a compound volcano, where the locus of activity (the active vent) has migrated to and fro by about 25 km. Here we review the RS03 vent complex and several similar examples. -

2021 PISD Attendancezone M

G Paradise Valley Dr l e Ola Ln Whisenant Dr Lake Highlands Dr Harvest Run Dr Loma Alta Dr n Lone Star Ct 1 Miners Creek Rd 2 3 Robincreek Ln 4 5 W 6 R S 7 8 9 10 11 12 Halyard Dr a J A e o r g u Rivercrest Blvd O D s s Cool Springs Dr n C i n D Royal Troon Dr e n g Dr l t r Rivercrest Blvd r a Whitney Ct r c Moonlight T o a Hagen Dr l Dr D Fannin Ct t c e R C e R d u Blondy Jhune Trl y L r w m h Dr Stinson Dr Barley Plac D io D Fieldstone Dr l Rd Patagonian Pl w o r w P n en i e D a e l o i i l Autumn Lake Dr a l Warren Pkwy v a N Crossing Dr rv i f e n be idg Hunters l im R Frosted Green Ln L C Village Way T l w t M i h k n r r c e r r r c n e e r P n a Creek Ct D b e k d m w S l e h n i y L p t i u D 1 Rattle Run Dr k T L o r e M Burnet Dr f W r Daisy Dr r r Citrus Way G d Trl Timberbend r Austin Dr D o Artemis Ct o o a e e d y ac Macrocarpa Rd dl t Anns D d e Est r ak t e C W e Dr Legacy w onste Pebblebrook Dr d e o r C B Savann g r a Heather Glen Dr r ll r r R s a v D C d D D a i Hillcrest Rd a t Saint Mary Dr l h o o Braxton Ln D r w p b o i Wills Point Dr Oakland Hills Dr L r o Lake Ridge Dr ri k t Skyvie u 316 h R a i L C Way r L N White Porch Rd Dr y n O Knott Ct e s Rid Lime Cv i d n r g o e e d Katrina Path Aransas Dr Duval Dr n L k d Vidalia Ln Temp t s Co e Cir Citrus Way b t o e R ra D W M c ws i a r N Malone Rd R e W e n re t Kingswoo Blo e Windsor Rdg i e D r D t fo n o ndy Jhun B Dr Shallowater r N Watters Rd S l r til ra k Shadetree Ln s PLANO y L o r B z apsta R w a n Haystack Dr C n e d o Cutter Ln d w D Cedardale -

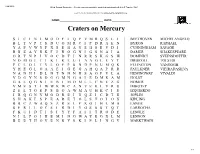

2D Mercury Crater Wordsearch V2

3/24/2019 Word Search Generator :: Create your own printable word find worksheets @ A to Z Teacher Stuff MAKE YOUR OWN WORKSHEETS ONLINE @ WWW.ATOZTEACHERSTUFF.COM NAME:_______________________________ DATE:_____________ Craters on Mercury SICINIMODFIQPVMRQSLJ BEETHOVEN MICHELANGELO BLTVPTSDUOMRCIPDRAEN BYRON RAPHAEL YAPVWYPXSEHAUEHSEVDI CUNNINGHAM SAVAGE RRZAYRKFJROGNIGSNAIA DAMER SHAKESPEARE ORTNPIVOCDTJNRRSKGSW DOMINICI SVEINSDOTTIR NOMGETIKLKEUIAAGLEYT DRISCOLL TOLSTOI PCLOLTVLOEPSNDPNUMQK ELLINGTON VANGOGH YHEGLOAAEIGEGAHQAPRR FAULKNER VIEIRADASILVA NANHIDLNTNNNHSAOFVLA HEMINGWAY VIVALDI VDGYNSDGGMNGAIEDMRAM HOLST GALQGNIEBIMOMLLCNEZG HOMER VMESTIWWKWCANVEKLVRU IMHOTEP ZELTOEPSBOAWMAUHKCIS IZQUIERDO JRQGNVMODREIUQZICDTH JOPLIN SHAKESPEARETOLSTOIOX KIPLING BBCZWAQSZRSLPKOJHLMA LANGE SFRLLOCSIRDIYGSSSTQT LARROCHA FKUIDTISIYYFAIITRODE LENGLE NILPOJHEMINGWAYEGXLM LENNON BEETHOVENRYSKIPLINGV MARKTWAIN 1/2 Mercury Craters: Famous Writers, Artists, and Composers: Location and Sizes Beethoven: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770−1827). German composer and pianist. 20.9°S, 124.2°W; Diameter = 630 km. Byron: Lord Byron (George Byron) (1788−1824). British poet and politician. 8.4°S, 33°W; Diameter = 106.6 km. Cunningham: Imogen Cunningham (1883−1976). American photographer. 30.4°N, 157.1°E; Diameter = 37 km. Damer: Anne Seymour Damer (1748−1828). English sculptor. 36.4°N, 115.8°W; Diameter = 60 km. Dominici: Maria de Dominici (1645−1703). Maltese painter, sculptor, and Carmelite nun. 1.3°N, 36.5°W; Diameter = 20 km. Driscoll: Clara Driscoll (1861−1944). American glass designer. 30.6°N, 33.6°W; Diameter = 30 km. Ellington: Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899−1974). American composer, pianist, and jazz orchestra leader. 12.9°S, 26.1°E; Diameter = 216 km. Faulkner: William Faulkner (1897−1962). American writer and Nobel Prize laureate. 8.1°N, 77.0°E; Diameter = 168 km. Hemingway: Ernest Hemingway (1899−1961). American journalist, novelist, and short-story writer. 17.4°N, 3.1°W; Diameter = 126 km. -

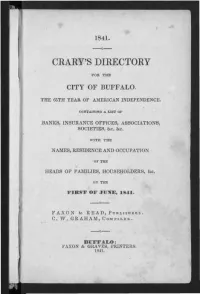

Crary's Directory

1841. CRARY'S DIRECTORY CITY OF BUFFALO. THE 65TH YEAR OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE. CONTAINING A LIST OF BANKS, INSURANCE OFFICES, ASSOCIATIONS, SOCIETIES, Sec. &c. WITH THE NAMES, RESIDENCE AND OCCUPATION OF THE HEADS OF FAMILIES, HOUSEHOLDERS, &c. ON THE FIRST OF JUNE, 1841. FAXON St READ, PUBLISHERS C. W. GRAHAM, COMPILER. BUFFALO: FAXON & GRAVES, PRINTERS. 1841. PREFACE. It will be allowed by all tbat a Directory fortfhe City of Buffalo is a work of absolute necessity, and that its hon appearance for a single year, would be attended with great inconvenience to citizens and strangers of all classes ; and yet all must admit, that a work of this kind has never as yet remunerated those who have been engaged in getting it up. Those who have been en gaged in it, have been certainly urged on by a hope of profit, as well as of adding to the conveniences of their fellow citizens,and yet that hope has proved delusive, as far as profit Has been concerned. Another attempt is now made, and although it does seem like hoping against hope, yet the subscriber will again try the public, under an assurance that if they will but consider the importance of his labors to all, they will yet make an effort to remunerate him and to en courage either him or another to continue a work of such great convenience. Every effort has been made to ensure correctness, and to obtain information, and it will be observed that the names of the colored portion of the community have been separated from the rest, as giving additional facil ity for discovering the residence of persons of the same name.