Detoxification of Heavy Metals (Soil Biology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Botanischer Garten Der Universität Tübingen

Botanischer Garten der Universität Tübingen 1974 – 2008 2 System FRANZ OBERWINKLER Emeritus für Spezielle Botanik und Mykologie Ehemaliger Direktor des Botanischen Gartens 2016 2016 zur Erinnerung an LEONHART FUCHS (1501-1566), 450. Todesjahr 40 Jahre Alpenpflanzen-Lehrpfad am Iseler, Oberjoch, ab 1976 20 Jahre Förderkreis Botanischer Garten der Universität Tübingen, ab 1996 für alle, die im Garten gearbeitet und nachgedacht haben 2 Inhalt Vorwort ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Baupläne und Funktionen der Blüten ......................................................................................... 9 Hierarchie der Taxa .................................................................................................................. 13 Systeme der Bedecktsamer, Magnoliophytina ......................................................................... 15 Das System von ANTOINE-LAURENT DE JUSSIEU ................................................................. 16 Das System von AUGUST EICHLER ....................................................................................... 17 Das System von ADOLF ENGLER .......................................................................................... 19 Das System von ARMEN TAKHTAJAN ................................................................................... 21 Das System nach molekularen Phylogenien ........................................................................ 22 -

Contribution À L'étude Du Genre Tamarix

REPUBLIQUE ALGERIENNE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE MINISTERE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPERIEURET DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE UNIVERSITE DE TLEMCEN Faculté des Sciences de la Nature etde la Vie et des Sciences de la Terre et de L’Univers Département d’Ecologie et Environnement Laboratoire de recherche d’écologie et gestion des écosystèmes naturels MEMOIREPrésenté par HADJ ALLAL Fatima zahra En vue de l’obtention du Magister En Ecologie Option : Phytodynamique des écosystèmes matorrals menacées Contribution à l'étude du genre Tamarix: aspects botanique et Phyto-écologique dans la région de Tlemcen Présenté le : Président : Mr BOUAZZA Mohamed Professeur Université de Tlemcen Encadreur :Mme STAMBOULI Hassiba M.C.A Université de Tlemcen Examinateurs : Mme MEDJAHDI Assia M.C.A Université de Tlemcen Mr MERZOUK Abdessamad M.C.A Université de Tlemcen Mr HASNAOUI Okkacha M.C.A Université de Saida Invité : Mr HASSANI Fayçal M.C.B Université de Tlemcen Année Universitaire 2013/2014 الملخص: هذهالدراسةمكرسةلدراسةجنساثل،معمراعاةالموكبالنباتيالتيتمتدعلىضفاف "واديتافنا" منحمامبوغرارة،إلىالبحراﻷبيضالمتوسط )راتشجون(. تمالتوصﻹلىالنتائجعلىجنساثلبشكلعام،بمافيذلكالجوانبالبيولوجية،البيوجغرافيواﻹيكولوجية. ويعكسالدراسةالنباتيالقحولةمتسلسلةمنالمنطقةبالحضورالقوىلﻷنواعتتحمﻻلجفافمثلكادرووسأتراكت يليسوبارباتوسشيسموس. خضعتهذهالنظماﻹيكولوجيةضخمةالواجبأساساالتغيراتاﻹنسانومناخالعمل؛تفضلهذاالتطورالتراجعي انتشاربعضاﻷنواعالشوكيةوالسامةالتيتهيمنالواضحلدينامجاﻻلدراسة. الكلماتالرئيسية: واديتافنااثل-متسامح-إيكو- المناخ،ومنطقةالدراسة Résumé : Cette étude est consacrée à l’étude du genre -

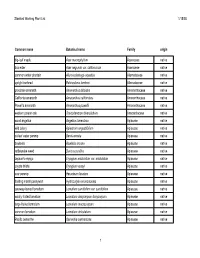

Plant List for Web Page

Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 Common name Botanical name Family origin big-leaf maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae native box elder Acer negundo var. californicum Aceraceae native common water plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae native upright burhead Echinodorus berteroi Alismataceae native prostrate amaranth Amaranthus blitoides Amaranthaceae native California amaranth Amaranthus californicus Amaranthaceae native Powell's amaranth Amaranthus powellii Amaranthaceae native western poison oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Anacardiaceae native wood angelica Angelica tomentosa Apiaceae native wild celery Apiastrum angustifolium Apiaceae native cutleaf water parsnip Berula erecta Apiaceae native bowlesia Bowlesia incana Apiaceae native rattlesnake weed Daucus pusillus Apiaceae native Jepson's eryngo Eryngium aristulatum var. aristulatum Apiaceae native coyote thistle Eryngium vaseyi Apiaceae native cow parsnip Heracleum lanatum Apiaceae native floating marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Apiaceae native caraway-leaved lomatium Lomatium caruifolium var. caruifolium Apiaceae native woolly-fruited lomatium Lomatium dasycarpum dasycarpum Apiaceae native large-fruited lomatium Lomatium macrocarpum Apiaceae native common lomatium Lomatium utriculatum Apiaceae native Pacific oenanthe Oenanthe sarmentosa Apiaceae native 1 Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 wood sweet cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae native mountain sweet cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Apiaceae native Gairdner's yampah (List 4) Perideridia gairdneri gairdneri Apiaceae -

JABG25P097 Barker

JOURNAL of the ADELAIDE BOTANIC GARDENS AN OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL FOR AUSTRALIAN SYSTEMATIC BOTANY flora.sa.gov.au/jabg Published by the STATE HERBARIUM OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA on behalf of the BOARD OF THE BOTANIC GARDENS AND STATE HERBARIUM © Board of the Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium, Adelaide, South Australia © Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Government of South Australia All rights reserved State Herbarium of South Australia PO Box 2732 Kent Town SA 5071 Australia © 2012 Board of the Botanic Gardens & State Herbarium, Government of South Australia J. Adelaide Bot. Gard. 25 (2011) 97–103 © 2012 Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Govt of South Australia Name changes associated with the South Australian census of vascular plants for the calendar year 2011 R.M. Barker & P.J. Lang and the staff and associates of the State Herbarium of South Australia State Herbarium of South Australia, DENR Science Resource Centre, P.O. Box 2732, Kent Town, South Australia 5071 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Keywords: Census, plant list, new species, introductions, weeds, native species, nomenclature, taxonomy. The following tables show the changes, and the phrase names in Eremophila, Spergularia, Caladenia reasons why they were made, in the census of South and Thelymitra being formalised, e.g. Eremophila sp. Australian vascular plants for the calendar year 2011. Fallax (D.E.Symon 12311) was the informal phrase The census is maintained in a database by the State name for the now formally published Eremophila fallax Herbarium of South Australia and projected on the Chinnock. -

Vascular Plants of Vina Plains Preserve Wurlitzer Unit

DO r:r:i :;:i·,iOVE Ff.'f)l,1 . ,- . - . "'I":; Vascular Plants of Vina Plains Preserve, Wurlitzer Unit Vernon H. Oswald Vaseular Plants of Vina Plains Preserve, Wurlitzer Unit Vernon H . Oswald Department of Biological Sciences California State University, C h ico Ch ico, California 95929-0515 1997 Revision RED BLUFF •CORN ING TEHAMA CO. -------------B1JITECO. ORLAND HWY 32 FIGURE I. Location of Vina P la.ins Preserve, Main Unit on the north, Wurlitzer Unit on the south. CONTENTS Figure 1. Location of Vina Plains Preserve ...... ................................. facing contents Figure 2. Wurlitzer Unit, Vina Plains Preserve ..... ............................... facing page I Introduction .. ... ..................................... ................................ ....... ....... ... ................ I References .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 4 The Plant List: Ferns and fem allies .......... ................................................... ........... ................. 5 Di cot flowering plants ............... ...................................................... ................. 5 Monocot flowering plants .......... ..................................................................... 25 / ... n\ a: t, i. FIGURE 2. Wurlitzer Unit, Vina Plains Preserve (in yellow), with a small comer of the Main Unit showing on the north. Modified from USGS 7.5' topographic maps, Richardson Springs NW & Nord quadrangles. - - INTRODUCTION 1 A survey of the vascular flora of the Wurl itzer -

VH Flora Complete Rev 18-19

Flora of Vinalhaven Island, Maine Macrolichens, Liverworts, Mosses and Vascular Plants Javier Peñalosa Version 1.4 Spring 2019 1. General introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------1.1 2. The Setting: Landscape, Geology, Soils and Climate ----------------------------------2.1 3. Vegetation of Vinalhaven Vegetation: classification or description? --------------------------------------------------3.1 The trees and shrubs --------------------------------------------------------------------------3.1 The Forest --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------3.3 Upland spruce-fir forest -----------------------------------------------------------------3.3 Deciduous woodlands -------------------------------------------------------------------3.6 Pitch pine woodland ---------------------------------------------------------------------3.6 The shore ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------3.7 Rocky headlands and beaches ----------------------------------------------------------3.7 Salt marshes -------------------------------------------------------------------------------3.8 Shrub-dominated shoreline communities --------------------------------------------3.10 Freshwater wetlands -------------------------------------------------------------------------3.11 Streams -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------3.11 Ponds -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------3.11 -

Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report

U.S. Geological Survey-National Park Service Vegetation Mapping Program Acadia National Park, Maine Project Report Revised Edition – October 2003 Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the U. S. Department of the Interior, U. S. Geological Survey. USGS-NPS Vegetation Mapping Program Acadia National Park U.S. Geological Survey-National Park Service Vegetation Mapping Program Acadia National Park, Maine Sara Lubinski and Kevin Hop U.S. Geological Survey Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center and Susan Gawler Maine Natural Areas Program This report produced by U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center 2630 Fanta Reed Road La Crosse, Wisconsin 54603 and Maine Natural Areas Program Department of Conservation 159 Hospital Street 93 State House Station Augusta, Maine 04333-0093 In conjunction with Mike Story (NPS Vegetation Mapping Coordinator) NPS, Natural Resources Information Division, Inventory and Monitoring Program Karl Brown (USGS Vegetation Mapping Coordinator) USGS, Center for Biological Informatics and Revised Edition - October 2003 USGS-NPS Vegetation Mapping Program Acadia National Park Contacts U.S. Department of Interior United States Geological Survey - Biological Resources Division Website: http://www.usgs.gov U.S. Geological Survey Center for Biological Informatics P.O. Box 25046 Building 810, Room 8000, MS-302 Denver Federal Center Denver, Colorado 80225-0046 Website: http://biology.usgs.gov/cbi Karl Brown USGS Program Coordinator - USGS-NPS Vegetation Mapping Program Phone: (303) 202-4240 E-mail: [email protected] Susan Stitt USGS Remote Sensing and Geospatial Technologies Specialist USGS-NPS Vegetation Mapping Program Phone: (303) 202-4234 E-mail: [email protected] Kevin Hop Principal Investigator U.S. -

Tamarix Parviflora Global Invasive

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Tamarix parviflora Tamarix parviflora System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Plantae Magnoliophyta Magnoliopsida Violales Tamaricaceae Common name tamarisk (English), saltcedar (English), tamarix (English), smallflower tamarisk (English), small-flower tamarisk (English) Synonym Tamarix tetrandra , auct. non Pallas Similar species Summary The smallflower tamarisk, Tamarix parviflora DC., is a semideciduous small tree or shrub that is native to Israel, Turkey and southeastern Europe. Seedlings of T. parviflora develop readily once established, and grow woody root systems that can reach as deep as 50 m into soil and rock. It can extract salts from soil and water excrete them through their branches and leaves. T. parviflora can have the following effects on ecological systems: dry up viable water sources; increase surface soil salinity; modification of hydrology; decrease native biodiversity of plants, invertebrates, birds, fish and reptiles; and increase fire risk. Management techniques that have been used to control T. parviflora include mechanical clearing - using both machinery and by hand - and/or herbicides. view this species on IUCN Red List Notes Tamarix parviflora Is thought to hybridise with the athel pine T. aphylla. (National Athel Pine Management Committee 2008). Global Invasive Species Database (GISD) 2021. Species profile Tamarix parviflora. Pag. 1 Available from: http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/species.php?sc=702 [Accessed 30 September 2021] FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Tamarix parviflora Management Info Management techniques that have been used to control Tamarix sp. include mechanical clearing - using both machinery and by hand - and/or herbicides. Hand-pulling is a very suitable control method when there are a few scattered seedlings, whilst other methods are more suitable for dense trees (excavation) and dense seedlings (stick raking, blade ploughing, ripping, root raking). -

Petition Number 08-315-01P for a Determination of Non-Regulated Status for Rosa X Hybrida Varieties IFD-52401-4 and IFD-52901-9 – ADDENDUM 1

FLORIGENE PTY LTD 1 PARK DRIVE BUNDOORA VICTORIA 3083 AUSTRALIA TEL +61 3 9243 3800 FAX +61 3 9243 3888 John Cordts USDA Unit 147 4700 River Rd Riverdale MD 20737-1236 USA DATE: 23/12/09 Subject: Petition number 08-315-01p for a determination of non-regulated status for Rosa X hybrida varieties IFD-52401-4 and IFD-52901-9 – ADDENDUM 1. Dear John, As requested Florigene is submitting “Addendum 1: pests and disease for roses” to add to petition 08-315-01p. This addendum outlines some of the common pest and diseases found in roses. It also includes information from our growers in California and Colombia stating that the two transgenic lines included in the petition are normal with regard to susceptibility and control. This addendum contains no CBI information. Kind Regards, Katherine Terdich Regulatory Affairs ADDENDUM 1: PEST AND DISEASE ISSUES FOR ROSES Roses like all plants can be affected by a variety of pests and diseases. Commercial production of plants free of pests and disease requires frequent observations and strategic planning. Prevention is essential for good disease control. Since the 1980’s all commercial growers use integrated pest management (IPM) systems to control pests and diseases. IPM forecasts conditions which are favourable for disease epidemics and utilises sprays only when necessary. The most widely distributed fungal disease of roses is Powdery Mildew. Powdery Mildew is caused by the fungus Podosphaera pannosa. It usually begins to develop on young stem tissues, especially at the base of the thorns. The fungus can also attack leaves and flowers leading to poor growth and flowers of poor quality. -

Flora and Fauna Specialist Assessment Report for the Proposed De Aar 2 South Grid Connection Near De Aar, Northern Cape Province

FLORA AND FAUNA SPECIALIST ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR THE PROPOSED DE AAR 2 SOUTH GRID CONNECTION NEAR DE AAR, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE On behalf of Mulilo De Aar 2 South (Pty) Ltd December 2020 Prepared By: Arcus Consultancy Services South Africa (Pty) Limited Office 607 Cube Workspace Icon Building Cnr Long Street and Hans Strijdom Avenue Cape Town 8001 T +27 (0) 21 412 1529 l E [email protected] W www.arcusconsulting.co.za Registered in South Africa No. 2015/416206/07 Flora & Fauna Impact Assessment Report De Aar 2 South Transmission Line and Switching Station TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Background .................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Assessment Philosophy .................................................................................. 4 1.3 Scope of Study ................................................................................................ 5 1.4 Assumptions and Limitations ......................................................................... 5 2 METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................................... 5 3 RESULTS .................................................................................................................... 5 3.1 Vegetation ...................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1 Northern Upper