Mindstream 1 Mindstream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 21 Spring 2016 Digital & Print-On-Demand

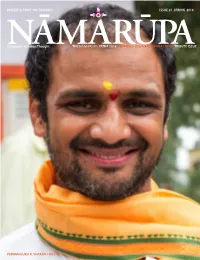

DIGITAL & PRINT-ON-DEMAND ISSUE 21 SPRING 2016 NĀMARŪPACategories of Indian Thought THE NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 ASHTANGA YOGA SADHANA RETREAT TRIBUTE ISSUE PARAMAGURU R. SHARATH JOIS NĀMARŪPA ISSUE 21 SPRING 2016 Categories of Indian Thought THE NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 ASHTANGA YOGA SADHANA RETREAT TRIBUTE ISSUE Publishers & Founding Editors Robert Moses & Eddie Stern NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 4 THE POSTER & ROUTE MAP Advisors Dr. Robert E. Svoboda GROUP PHOTOGRAPH 6 NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 Meenakshi Moses PALLAVI SHARMA DUFFY 8 WELCOME SPEECH Jocelyne Stern During the Folk Festival at Editors Vishnudevananda Tapovan Kuti Eddie Stern & Meenakshi Moses Design & Production Robert Moses PARAMAGURU 10 CONFERENCES AT TAPOVAN KUTI Proofreading & Transcription R. SHARATH JOIS Transcriptions of talks after class Meenakshi Moses Melanie Parker ROBERT MOSES 28 PHOTO ESSAY Megan Weaver Ashtanga Yoga Sadhana Retreat October 2015 Meneka Siddhu Seetharaman Website www.namarupa.org by BRAHMA VIDYA PEETH Roberto Maiocchi & Robert Moses ACHARYAS 48 TALKS ON INDIAN CULTURE All photographs in Issue 21 SWAMI SHARVANANDA Robert Moses except where noted. SWAMI HARIBRAMENDRANANDA Cover: R. Sharath Jois at Vishwanath Mandir, Uttarkashi, Himalayas. SWAMI MITRANANDA 58 NAVARATRI Back cover: Welcome sign at Kashi Vishwanath Mandir, Uttarkashi. SUAN LIN 62 FINE ART PHOTOGRAPHS October 13, 2015. Analog photography during Yatra 2015 SATYA MOSES DAŚĀVATĀRA ILLUSTRATIONS NĀMARŪPA Categories of Indian Thought, established in 2003, honors the many systems of knowledge, prac- tical and theoretical, that have origi- nated in India. Passed down through अ आ इ ई उ ऊ the ages, these systems have left tracks, a ā i ī u ū paths already traveled that can guide ए ऐ ओ औ us back to the Self—the source of all e ai o au names NĀMA and forms RŪPA. -

The Foundation of All Good Qualities by Lama Tsongkhapa

PRACTICE The Foundation of All Good Qualities By Lama Tsongkhapa In the 11th century, Tibet was blessed by the arrival of capacities of varying practitioners — small, medium, and the Indian Buddhist master Lama Atisha. Motivated to pres- great — which organize practices and meditations on the ent an organized summary of the sutra teachings, Atisha path into gradual stages. composed a short text entitled, The Lamp of the Path. Three Lama Tsongkhapa's famous prayer, The Foundation of hundred years later, Lama Tsongkhapa expanded upon this All Good Qualities, is the most concise and stirring outline text with his opus The Great Exposition on the Stages of the available of the Lam-Rim teachings. In only fourteen stanzas, Path to Enlightenment (Lamrim Chenmo). The often referred Tsongkhapa offers us a prayer that covers the entire graduated to "Lam-Rim teachings" are taken from this seminal text. path to enlightenment, short enough to recite every day, The teachings are presented in three scopes according to the profound enough to study for a lifetime. The foundation of all good qualities is the kind and venerable guru; I will not achieve enlightenment. Correct devotion to him is the root of the path. With my clear recognition of this. By clearly seeing this and applying great effort, Please bless me to practice the bodhisattva vows with great energy. Please bless me to rely upon him with great respect. Once I have pacified distractions to wrong objects Understanding that the precious freedom of this rebirth is found And correctly analyzed the meaning of reality, only once. -

Opening Speech Liao Yiwu

About the 17th Karmapa Liao Yiwu On the morning of 4 June, 1989, a contingent of over two hundred thousand soldiers surrounded the Chinese capital of Beijing, where they opened fire on unarmed protesters in a massacre at Tiananmen Square that shook the entire world. On 5 March of that same year, there had been another large massacre in the Tibetan capital of Lhasa, news of this earlier event had been effectively suppressed. Because of the absence of the Western news media, the PLA’s cold- blooded killing of Tibetan protesters was never recorded on camera. The holy city of Lhasa was about ten times smaller than Beijing at that time, and Bajiao Square where the massacre took place was about ten times smaller than Tiananmen Square, and yet over ten thousand peaceful protesters assembled in that narrow square, where they clashed with some fifteen thousand heavily-armed soldiers. As a result of this encounter, more than three hundred civilians lost their lives, another three thousand were imprisoned, and the “worst offenders” were subsequently sentenced to death. The Jokhang Temple located next to the Potala Palace was attacked and occupied by army troops because it was flying the Snow Lion Flag of Tibetan independence, and it was burned to the ground along with its precious copy of the Pagoda Scriptures, a text which symbolizes the dignity of Tibetan Esoteric Buddhism. Tens of thousands of Tibetan Buddhists stood in the street bewailing the loss of their sacred text, and the lamas continually tried to rush into the burning temple to rescue the scriptures, but were shot down amidst the flames. -

The Meaning of “Zen”

MATSUMOTO SHIRÕ The Meaning of “Zen” MATSUMOTO Shirõ N THIS ESSAY I WOULD like to offer a brief explanation of my views concerning the meaning of “Zen.” The expression “Zen thought” is not used very widely among Buddhist scholars in Japan, but for Imy purposes here I would like to adopt it with the broad meaning of “a way of thinking that emphasizes the importance or centrality of zen prac- tice.”1 The development of “Ch’an” schools in China is the most obvious example of how much a part of the history of Buddhism this way of think- ing has been. But just what is this “zen” around which such a long tradition of thought has revolved? Etymologically, the Chinese character ch’an 7 (Jpn., zen) is thought to be the transliteration of the Sanskrit jh„na or jh„n, a colloquial form of the term dhy„na.2 The Chinese characters Ï (³xed concentration) and ÂR (quiet deliberation) were also used to translate this term. Buddhist scholars in Japan most often used the com- pound 7Ï (zenjõ), a combination of transliteration and translation. Here I will stick with the simpler, more direct transliteration “zen” and the original Sanskrit term dhy„na itself. Dhy„na and the synonymous sam„dhi (concentration), are terms that have been used in India since ancient times. It is well known that the terms dhy„na and sam„hita (entering sam„dhi) appear already in Upani- ¤adic texts that predate the origins of Buddhism.3 The substantive dhy„na derives from the verbal root dhyai, and originally meant deliberation, mature reµection, deep thinking, or meditation. -

Beyond Mind II: Further Steps to a Metatranspersonal Philosophy and Psychology Elías Capriles University of the Andes

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 25 | Issue 1 Article 3 1-1-2006 Beyond Mind II: Further Steps to a Metatranspersonal Philosophy and Psychology Elías Capriles University of the Andes Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Capriles, E. (2006). Capriles, E. (2006). Beyond mind II: Further steps to a metatranspersonal philosophy and psychology. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 25(1), 1–44.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 25 (1). http://dx.doi.org/ 10.24972/ijts.2006.25.1.1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Beyond Mind II: Further Steps to a Metatranspersonal Philosophy and Psychology Elías Capriles University of The Andes Mérida, Venezuela Some of Wilber’s “holoarchies” are gradations of being, which he views as truth itself; however, being is delusion, and its gradations are gradations of delusion. Wilber’s supposedly universal ontogenetic holoarchy contradicts all Buddhist Paths, whereas his view of phylogeny contradicts Buddhist Tantra and Dzogchen, which claim delusion/being increase throughout the aeon to finally achieve reductio ad absur- dum. Wilber presents spiritual healing as ascent; Grof and Washburn represent it as descent—yet they are all equally off the mark. -

Early Buddhist Concepts in Today's Language

1 Early Buddhist Concepts In today's language Roberto Thomas Arruda, 2021 (+55) 11 98381 3956 [email protected] ISBN 9798733012339 2 Index I present 3 Why this text? 5 The Three Jewels 16 The First Jewel (The teachings) 17 The Four Noble Truths 57 The Context and Structure of the 59 Teachings The second Jewel (The Dharma) 62 The Eightfold path 64 The third jewel(The Sangha) 69 The Practices 75 The Karma 86 The Hierarchy of Beings 92 Samsara, the Wheel of Life 101 Buddhism and Religion 111 Ethics 116 The Kalinga Carnage and the Conquest by 125 the Truth Closing (the Kindness Speech) 137 ANNEX 1 - The Dhammapada 140 ANNEX 2 - The Great Establishing of 194 Mindfulness Discourse BIBLIOGRAPHY 216 to 227 3 I present this book, which is the result of notes and university papers written at various times and in various situations, which I have kept as something that could one day be organized in an expository way. The text was composed at the request of my wife, Dedé, who since my adolescence has been paving my Dharma with love, kindness, and gentleness so that the long path would be smoother for my stubborn feet. It is not an academic work, nor a religious text, because I am a rationalist. It is just what I carry with me from many personal pieces of research, analyses, and studies, as an individual object from which I cannot separate myself. I dedicate it to Dede, to all mine, to Prof. Robert Thurman of Columbia University-NY for his teachings, and to all those to whom this text may in some way do good. -

Women's Studies Quarterly

!" #$%%!& #' ()( **+++, - ,**)+ . ! "# /0 (1 )231 4 ( ! " !"# $%& '()*++'',- 4 1 ( ! "# $ % ! & % ' !( ) * )+ #%, %% -.#/+ 0%!!% !%0 % )))% 0 ! # %! & %10 #% 2& %+ 3) WOMEN'S STUDIES BOOK REVIEW Sami Schalk. Bodyminds Reimagined: (Dis)ability, Race, and Gender in Black Women’s Speculative Fiction. Duke UP, 2018. Bodyminds Reimagined is a compelling critical study of the points of contact and convergence between disability studies and Black feminist studies in contemporary Black women ’s spec- ulative fiction. In the first monograph focusing exclusively on the representation of disability by Black authors, Schalk meticulously sketches the contours of the various fields with which Bodyminds Reimagined converses. Schalk begins with the stance that “(dis)ability is rarely accounted for in black feminist theory ” and that disability studies “has often avoided issues of race ” (3 –4). Speculative fiction, Schalk argues, is a rich site to interrogate the contact between Black feminist theory and disability studies because the nonrealist genre elements allow authors to “reimagine the possibilities of bodyminds ” (17) and posit alternative constructions of identity in nonreal worlds that in turn “force readers to question the ideologies undergirding these categories ” (18). Bodyminds Reimagined considers Black women ’s speculative fiction published after 1970 using a three-pronged methodology: rejecting the good/bad binary that characterizes much scholarship on representations of disability; attending to more than just character analysis in close reading individual texts; and approaching speculative worlds on their own terms and reading them through their nonrealist rules. Bodyminds Reimagined is not only a vital examination of disability within Black fiction, but also a methodological manual of sorts for scholars inspired to continue this intellectual project. But what is a “bodymind ”? Schalk borrows this vocabulary from the materialist feminist disability scholarship by Margaret Price. -

Training in Wisdom 6 Yogacara, the ‘Mind Only’ School: Buddha Nature, 5 Dharmas, 8 Kinds of Consciousness, 3 Svabhavas

Training in Wisdom 6 Yogacara, the ‘Mind Only’ School: Buddha Nature, 5 Dharmas, 8 kinds of Consciousness, 3 Svabhavas The Mind Only school evolved as a response to the possible nihilistic interpretation of the Madhyamaka school. The view “everything is mind” is conducive to the deep practice of meditational yogas. The “Tathagatagarbha”, the ‘Buddha Nature’ was derived from the experience of the Dharmakaya. Tathagata, the ‘Thus Come one’ is a name for a Buddha ( as is Sugata, the ‘Well gone One’ ). Garbha means ‘embryo’ and ‘womb’, the container and the contained, the seed of awakening . This potential to attain Buddhahood is said to be inherent in every sentient being but very often occluded by kleshas, ( ‘negative emotions’) and by cognitive obscurations, by wrong thinking. These defilements are adventitious, and can be removed by practicing Buddhist yogas and trainings in wisdom. Then the ‘Sun of the Dharma’ breaks through the clouds of obscurations, and shines out to all sentient beings, for great benefit to self and others. The 3 svabhavas, 3 kinds of essential nature, are unique to the mind only theory. They divide what is usually called ‘conventional truth’ into two: “Parakalpita” and “Paratantra”. Parakalpita refers to those phenomena of thinking or perception that have no basis in fact, like the water shimmering in a mirage. Usual examples are the horns of a rabbit and the fur of a turtle. Paratantra refers to those phenomena that come about due to cause and effect. They have a conventional actuality, but ultimately have no separate reality: they are empty. Everything is interconnected. -

Catazacke 20200425 Bd.Pdf

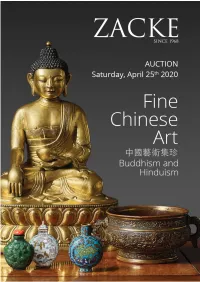

Provenances Museum Deaccessions The National Museum of the Philippines The Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University New York, USA The Monterey Museum of Art, USA The Abrons Arts Center, New York, USA Private Estate and Collection Provenances Justus Blank, Dutch East India Company Georg Weifert (1850-1937), Federal Bank of the Kingdom of Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia Sir William Roy Hodgson (1892-1958), Lieutenant Colonel, CMG, OBE Jerrold Schecter, The Wall Street Journal Anne Marie Wood (1931-2019), Warwickshire, United Kingdom Brian Lister (19262014), Widdington, United Kingdom Léonce Filatriau (*1875), France S. X. Constantinidi, London, United Kingdom James Henry Taylor, Royal Navy Sub-Lieutenant, HM Naval Base Tamar, Hong Kong Alexandre Iolas (19071987), Greece Anthony du Boulay, Honorary Adviser on Ceramics to the National Trust, United Kingdom, Chairman of the French Porcelain Society Robert Bob Mayer and Beatrice Buddy Cummings Mayer, The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago Leslie Gifford Kilborn (18951972), The University of Hong Kong Traudi and Peter Plesch, United Kingdom Reinhold Hofstätter, Vienna, Austria Sir Thomas Jackson (1841-1915), 1st Baronet, United Kingdom Richard Nathanson (d. 2018), United Kingdom Dr. W. D. Franz (1915-2005), North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany Josette and Théo Schulmann, Paris, France Neil Cole, Toronto, Canada Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald (19021982) Arthur Huc (1854-1932), La Dépêche du Midi, Toulouse, France Dame Eva Turner (18921990), DBE Sir Jeremy Lever KCMG, University -

A Comparative Study of Bhavacakra Painting

Historical Journal Volume: 12 Number: 1 Shrawan, 2077 Deepak Dong Tamang A Comparative Study of Bhavacakra Painting Deepak Dong Tamang Abstract The Bhavacakra is a symbolic representation of Samsara, a powerful mirror for spiritual aspirants and it is often painted to the left of Tibetan monastery doors. Bhavacakra, ‘wheel of life’ consists of two Sanskrit words ‘Bhava’ and ‘Cakra’. The word bhava means birth, origin, existing etc and cakra means wheel, circle, round, etc. There are some textual materials which suggest that the Bhavacakra painting began during the Buddha lifetime. Bhavacakra is very famous for wall and cloth painting. It is believed to represent the knowledge of release from suffering gained by Gautama Buddha in the course of his meditation. This symbolic representation of Bhavacakra serves as a wonderful summary of what Buddhism is, and also reminds that every action has consequences. It can be also understood by the illiterate persons not needing high education and it shows the path of enlightenment out of suffering in samsara. Mahayana Buddhism is very popular in Asian countries like northern Nepal, India, Bhutan, China, Korean, Japan and Mongolia. So in these countries every Mahayana monastery there is wall painting and Thānkā painting of Bhavacakra. But in these countries there are various designs of Bhavacakra due to artist, culture and nation. Key words: Bhavacakra, wheel of life, Mandala, Karma, Samsāra, Sukhāvati bhuvan, Thānkā Introduction In Buddhism, art has been one of the best tools to understand the Buddha teaching. The wheel of life is very famous for walls and cloth painting. This classical image from the Tibetan Buddhist tradition depicts the psychological states, or realm of existence, associated with an unenlightened state. -

AyyaYeshe How To Be A

Ayya Yeshe How to Be a Light for Yourself and Others in Challenging Times Week One: “Establishing the Basis for Dharma Practice” September 4, 2017 Hi, I'm Ayya Yeshe. I'm an Australian Buddhist nun and I've been ordained 16 years. I'm the director of Bodhicitta Foundation, a charity for people in the slums of Central India, which has been running for over a decade. I'm also the founding abbess of a monastery in Australia, which we are currently raising funds for, called Khandro Ling Hermitage. I'm mainly from the Sakya tradition but I was ordained as a fully ordained nun by Thich Nhat Hanh, the Nobel Peace Prize nominee and Vietnamese Zen master. Today I would like to talk about The Seven Points of Mind Training by Geshe Chekawa, which is mainly from the Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. It's actually quite a long and involved text but it's a wonderful introduction to Mahayana Buddhism. As we go through the text, I hope that I can make some of -

Relevance of Pali Tipinika Literature to Modern World

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) Vol. 1, Issue 2, July 2013, 83-92 © Impact Journals RELEVANCE OF PALI TIPINIKA LITERATURE TO MODERN WORLD GYANADITYA SHAKYA Assistant Professor, School of Buddhist Studies & Civilization, Gautam Buddha University, Greater Noida, Gautam Buddha Nagar, Uttar Pradesh, India ABSTRACT Shakyamuni Gautam Buddha taught His Teachings as Dhamma & Vinaya. In his first sermon Dhammacakkapavattana-Sutta, after His enlightenment, He explained the middle path, which is the way to get peace, happiness, joy, wisdom, and salvation. The Buddha taught The Eightfold Path as a way to Nibbana (salvation). The Eightfold Path can be divided into morality, mental discipline, and wisdom. The collection of His Teachings is known as Pali Tipinika Literature, which is compiled into Pali (Magadha) language. It taught us how to be a nice and civilized human being. By practicing Sala (Morality), Samadhi (Mental Discipline), and Panna (Wisdom ), person can eradicate his all mental defilements. The whole theme of Tipinika explains how to be happy, and free from sufferings, and how to get Nibbana. The Pali Tipinika Literature tried to establish freedom, equality, and fraternity in this world. It shows the way of freedom of thinking. The most basic human rights are the right to life, freedom of worship, freedom of speech, freedom of thought and the right to be treated equally before the law. It suggests us not to follow anyone blindly. The Buddha opposed harmful and dangerous customs, so that this society would be full of happiness, and peace. It gives us same opportunity by providing human rights.