Opening Speech Liao Yiwu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Location: Tibet Lies at the Centre of Asia, with an Area of 2.5 Million Square Kilometers. the Earth's Highest Mountains, a Vast

Location: Tibet lies at the centre of Asia, with an area of 2.5 million square kilometers. The earth's highest mountains, a vast arid plateau and great river valleys make up the physical homeland of 6 million Tibetans. It has an average altitude of 13,000 feet above sea level. Capital: Lhasa Population: 6 million Tibetans and an estimated 7.5 million Chinese, most of whom are in Kham and Amdo. Language: Tibetan (of the Tibeto-Burmese language family). The official language is Chinese. Tibet is comprised of the three provinces of Amdo (now split by China into the provinces of Qinghai, Gansu & Sichuan), Kham (largely incorporated into the Chinese provinces of Sichuan, Yunnan and Qinghai), and U-Tsang (which, together with western Kham, is today referred to by China as the Tibet Autonomous Region). The Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) comprises less than half of historic Tibet and was created by China in 1965 for administrative reasons. It is important to note that when Chinese officials and publications use the term "Tibet" they mean only the TAR. Tibetans use the term Tibet to mean the three provinces described above, i.e., the area traditionally known as Tibet before the 1949-50 invasion. Today Tibetans are outnumbered by Han Chinese population in their own homeland, there are est. 6 million Tibetans and an estimated 7.5 million Chinese, most of whom are in Kham and Amdo. The official language is Chinese. But those Tibetans living in exile still speak, read and write in Tibetan (of the Tibeto-Burmese language family). -

OM MANI PADME HUM the Jewel Is in the Lotus Or Praise to the Jewel In

On the meaning of: OM MANI PADME HUM The jewel is in the lotus or praise to the jewel in the lotus by His Holiness Tenzin Gyatso The Fourteenth Dalai Lama of Tibet It is very good to recite the mantra OM MANI PADME HUM, but while you are doing it, you should be thinking on its meaning, for the meaning of the six syllables is great and vast. The first, OM, is composed of three pure letters, A, U, and M. These symbolize the practitioner's impure body, speech, and mind; they also symbolize the pure exalted body, speech and mind of a Buddha. Can impure body, speech and mind be transformed into pure body, speech and mind, or are they entirely separate? All Buddhas are cases of being who were like ourselves and then in dependence on the path became enlightened; Buddhism does not assert that there is anyone who from the beginning is free from faults and possesses all good qualities. The development of pure body, speech, and mind comes from gradually leaving the impure states and their being transformed into the pure. How is this done? The path is indicated by the next four syllables. MANI, meaning jewel, symbolizes the factor of method- the altruistic intention to become enlightened, compassion, and love. Just as a jewel is capable of removing poverty, so the altruistic mind of enlightenment is capable of removing the poverty, or difficulties, of cyclic existence and of solitary peace. Similarly, just as a jewel fulfills the wishes of sentient beings, so the altruistic intention to become enlightened fulfills the wishes of sentient beings. -

His Holiness the Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje, to Visit University of Redlands in Rare U.S

His Holiness the Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje, to visit University of Redlands in rare U.S. tour March 18, 2015 The University of Redlands will welcome His Holiness the Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje, to campus March 24, 2015, as the only Southern California stop on his third trip to the United States. Reigniting a years-long connection with the University and special bond with students, the Karmapa will interact with Redlands students, faculty, and alumni and accept an Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree, presented by University President Ralph Kuncl. He will then offer a public lecture, "Living Interdependence," at 7 p.m. in Memorial Chapel. The Karmapa heads the 900-year-old Karma Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism and guides millions of Buddhists around the world. At the age of 14, he made a dramatic escape from Tibet to India to be near His Holiness the Dalai Lama and his own lineage teachers. Currently 29 years old, the Karmapa is a leader of the new century. He created an eco- monastic movement with over 55 monasteries across the Himalayan region acting as centers of environmental activism. Leading on women's issues, he recently announced plans to establish full ordination for women, a step that will change the future of Tibetan Buddhism. His latest book, The Heart is Noble: Changing the World from the Inside Out, co-edited by University of Redlands Professor of Religious Studies and Virginia C. Hunsaker Distinguished Teaching Chair, Karen Derris, the Karmapa speaks to the younger generation on the major challenges facing society today, including gender issues, food justice, rampant consumerism and the environmental crisis. -

The Meaning of the Short Chenrezig Mantra, Om Mani Padme Hum

Kopan Monastery Prayers and Practices Downloaded from www.kopanmonastery.com The Meaning Of The Short Chenrezig Mantra, Om Mani Padme Hum MANI is method, PADME is wisdom; so MANI PADME is method-wisdom. Buddha revealed the lesser vehicle teachings, the Mahayana paramitayana teachings and the mahayana vajrayana teachings. There is method-wisdom in the lesser vehicle teachings, method-wisdom in the mahayana paramitayana teachings and method-wisdom in the mahayana Vajrayana teachings. So MANI PADME contains everything: the hinayana lesser vehicle teachings of method-wisdom, the mahayana paramitayana method-wisdom and the mahayana vajrayana method-wisdom. By practising method-wisdom together, as signified by MANI PADME, one purifies the stains of body, speech and mind. This is signified by the OM - A U MA - these three sounds integrate to make OM, which signifies the vajra holy body, holy speech and holy mind of Buddha. By practising the method-wisdom signified by MANI PADME together, one purifies one's own ordinary body, speech and mind and they become inseparable from Buddha's vajra holy body, holy speech and holy mind. So the OM - AH U MA - signifies the three vajras. Then, MANI PADME also signifies the mahaanuttarayoga tantra path. What I explained before is general. Now, more specifically, by depending on the path of the generation stage, which is the method of the profound secret mantra that ripens the mind, and on the completion stage, which liberates the mind, you can cease the circle of suffering, the base-time ordinary birth, death and intermediate state; actualize the path-time dharmakaya, sambhogakaya, nirmanakaya; and achieve the result-time dharmakaya, sambhogakaya, nirmanakaya. -

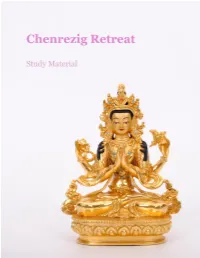

Chenrezig Practice

1 Chenrezig Practice Collected Notes Bodhi Path Natural Bridge, VA February 2013 These notes are meant for private use only. They cannot be reproduced, distributed or posted on electronic support without prior explicit authorization. Version 1.00 ©Tsony 2013/02 2 About Chenrezig © Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche in Heart Treasure of the Enlightened One. ISBN-10: 0877734933 ISBN-13: 978-0877734932 In the Tibetan Buddhist pantheon of enlightened beings, Chenrezig is renowned as the embodiment of the compassion of all the Buddhas, the Bodhisattva of Compassion. Avalokiteshvara is the earthly manifestation of the self born, eternal Buddha, Amitabha. He guards this world in the interval between the historical Sakyamuni Buddha, and the next Buddha of the Future Maitreya. Chenrezig made a a vow that he would not rest until he had liberated all the beings in all the realms of suffering. After working diligently at this task for a very long time, he looked out and realized the immense number of miserable beings yet to be saved. Seeing this, he became despondent and his head split into thousands of pieces. Amitabha Buddha put the pieces back together as a body with very many arms and many heads, so that Chenrezig could work with myriad beings all at the same time. Sometimes Chenrezig is visualized with eleven heads, and a thousand arms fanned out around him. Chenrezig may be the most popular of all Buddhist deities, except for Buddha himself -- he is beloved throughout the Buddhist world. He is known by different names in different lands: as Avalokiteshvara in the ancient Sanskrit language of India, as Kuan-yin in China, as Kannon in Japan. -

Big Love: Mandala Magazine Article

LAMA YESHE, PASHUPATINATH TEMPLE, NEPAL, 1980. PHOTO BY TOM CASTLES, COURTESY OF LAMA YESHE WISDOM ARCHIVE. 26 MANDALA | July - December 2019 A MONUMENTAL ACCOMPLISHMENT: THE MAKING OF Big Love BY LAURA MILLER The creation of FPMT founder Lama Yeshe’s official biography has been a monumental task. Work on the forthcoming book, Big Love: The Life and Teachings of Lama Yeshe, has spanned three decades. To understand the significance of this project as it draws to a close, Mandala talked to three key people, all early students of Lama Yeshe, about the production of the book: Adele Hulse, Big Love’s author; Peter Kedge, who initiated and helped fund the project; and Nicholas Ribush, who is overseeing the book’s publication at the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. Big Love: The Life and Teachings of Lama Yeshe begins with a refugee Tibetan monks. Together, the two lamas encountered their simple dedication: “This book is dedicated to you, the reader. first Western student, Zina Rachevsky, in 1967 in Darjeeling. The If you met Lama during your life, may you feel his presence here. following year, they went to Nepal, where they soon established If you never met Lama, then come with us—walk up the hill to Kopan Monastery on the outskirts of Kathmandu and later Kopan and meet Lama Yeshe, as thousands did, without knowing founded the international FPMT organization. anything of Buddhism or Tibet. That came later.” “Since then, His Holiness the Dalai Lama has been to many Within the biography’s nearly 1,400 pages, Lama Yeshe comes countries and now has a great reputation and has received many to life. -

The Lhasa Jokhang – Is the World's Oldest Timber Frame Building in Tibet? André Alexander*

The Lhasa Jokhang – is the world's oldest timber frame building in Tibet? * André Alexander Abstract In questo articolo sono presentati i risultati di un’indagine condotta sul più antico tempio buddista del Tibet, il Lhasa Jokhang, fondato nel 639 (circa). L’edificio, nonostante l’iscrizione nella World Heritage List dell’UNESCO, ha subito diversi abusi a causa dei rifacimenti urbanistici degli ultimi anni. The Buddhist temple known to the Tibetans today as Lhasa Tsuklakhang, to the Chinese as Dajiao-si and to the English-speaking world as the Lhasa Jokhang, represents a key element in Tibetan history. Its foundation falls in the dynamic period of the first half of the seventh century AD that saw the consolidation of the Tibetan empire and the earliest documented formation of Tibetan culture and society, as expressed through the introduction of Buddhism, the creation of written script based on Indian scripts and the establishment of a law code. In the Tibetan cultural and religious tradition, the Jokhang temple's importance has been continuously celebrated soon after its foundation. The temple also gave name and raison d'etre to the city of Lhasa (“place of the Gods") The paper attempts to show that the seventh century core of the Lhasa Jokhang has survived virtually unaltered for 13 centuries. Furthermore, this core building assumes highly significant importance for the fact that it represents authentic pan-Indian temple construction technologies that have survived in Indian cultural regions only as archaeological remains or rock-carved copies. 1. Introduction – context of the archaeological research The research presented in this paper has been made possible under a cooperation between the Lhasa City Cultural Relics Bureau and the German NGO, Tibet Heritage Fund (THF). -

An Annotated List of Birds Wintering in the Lhasa River Watershed and Yamzho Yumco, Tibet Autonomous Region, China

FORKTAIL 23 (2007): 1–11 An annotated list of birds wintering in the Lhasa river watershed and Yamzho Yumco, Tibet Autonomous Region, China AARON LANG, MARY ANNE BISHOP and ALEC LE SUEUR The occurrence and distribution of birds in the Lhasa river watershed of Tibet Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China, is not well documented. Here we report on recent observations of birds made during the winter season (November–March). Combining these observations with earlier records shows that at least 115 species occur in the Lhasa river watershed and adjacent Yamzho Yumco lake during the winter. Of these, at least 88 species appear to occur regularly and 29 species are represented by only a few observations. We recorded 18 species not previously noted during winter. Three species noted from Lhasa in the 1940s, Northern Shoveler Anas clypeata, Solitary Snipe Gallinago solitaria and Red-rumped Swallow Hirundo daurica, were not observed during our study. Black-necked Crane Grus nigricollis (Vulnerable) and Bar-headed Goose Anser indicus are among the more visible species in the agricultural habitats which dominate the valley floors. There is still a great deal to be learned about the winter birds of the region, as evidenced by the number of apparently new records from the last 15 years. INTRODUCTION limited from the late 1940s to the early 1980s. By the late 1980s the first joint ventures with foreign companies were The Lhasa river watershed in Tibet Autonomous Region, initiated and some of the first foreign non-governmental People’s Republic of China, is an important wintering organisations were allowed into Tibet, enabling our own area for a number of migratory and resident bird species. -

Catazacke 20200425 Bd.Pdf

Provenances Museum Deaccessions The National Museum of the Philippines The Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University New York, USA The Monterey Museum of Art, USA The Abrons Arts Center, New York, USA Private Estate and Collection Provenances Justus Blank, Dutch East India Company Georg Weifert (1850-1937), Federal Bank of the Kingdom of Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia Sir William Roy Hodgson (1892-1958), Lieutenant Colonel, CMG, OBE Jerrold Schecter, The Wall Street Journal Anne Marie Wood (1931-2019), Warwickshire, United Kingdom Brian Lister (19262014), Widdington, United Kingdom Léonce Filatriau (*1875), France S. X. Constantinidi, London, United Kingdom James Henry Taylor, Royal Navy Sub-Lieutenant, HM Naval Base Tamar, Hong Kong Alexandre Iolas (19071987), Greece Anthony du Boulay, Honorary Adviser on Ceramics to the National Trust, United Kingdom, Chairman of the French Porcelain Society Robert Bob Mayer and Beatrice Buddy Cummings Mayer, The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago Leslie Gifford Kilborn (18951972), The University of Hong Kong Traudi and Peter Plesch, United Kingdom Reinhold Hofstätter, Vienna, Austria Sir Thomas Jackson (1841-1915), 1st Baronet, United Kingdom Richard Nathanson (d. 2018), United Kingdom Dr. W. D. Franz (1915-2005), North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany Josette and Théo Schulmann, Paris, France Neil Cole, Toronto, Canada Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald (19021982) Arthur Huc (1854-1932), La Dépêche du Midi, Toulouse, France Dame Eva Turner (18921990), DBE Sir Jeremy Lever KCMG, University -

Escape to Lhasa Strategic Partner

4 Nights Incentive Programme Escape to Lhasa Strategic Partner Country Name Lhasa, the heart and soul of Tibet, is a city of wonders. The visits to different sites in Lhasa would be an overwhelming experience. Potala Palace has been the focus of the travelers for centuries. It is the cardinal landmark and a structure of massive proportion. Similarly, Norbulingka is the summer palace of His Holiness Dalai Lama. Drepung Monastery is one of the world’s largest and most intact monasteries, Jokhang temple the heart of Tibet and Barkhor Market is the place to get the necessary resources for locals as well as souvenirs for tourists. At the end of this trip we visit the Samye Monastery, a place without which no journey to Tibet is complete. StrategicCountryPartner Name Day 1 Arrive in Lhasa Country Name Day 1 o Morning After a warm welcome at Gonggar Airport (3570m) in Lhasa, transfer to the hotel. Distance (Airport to Lhasa): 62kms/ 32 miles Drive Time: 1 hour approx. Altitude: 3,490 m/ 11,450 ft. o Leisure for acclimatization Lhasa is a city of wonders that contains many culturally significant Tibetan Buddhist religious sites and lies in a valley next to the Lhasa River. StrategicCountryPartner Name Day 2 In Lhasa Country Name Day 2 o Morning: Set out to visit Sera and Drepung Monasteries Founded in 1419, Sera Monastery is one of the “great three” Gelukpa university monasteries in Tibet. 5km north of Lhasa, the Sera Monastery’s setting is one of the prettiest in Lhasa. The Drepung Monastery houses many cultural relics, making it more beautiful and giving it more historical significance. -

THE SECURITISATION of TIBETAN BUDDHISM in COMMUNIST CHINA Abstract

ПОЛИТИКОЛОГИЈА РЕЛИГИЈЕ бр. 2/2012 год VI • POLITICS AND RELIGION • POLITOLOGIE DES RELIGIONS • Nº 2/2012 Vol. VI ___________________________________________________________________________ Tsering Topgyal 1 Прегледни рад Royal Holloway University of London UDK: 243.4:323(510)”1949/...” United Kingdom THE SECURITISATION OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM IN COMMUNIST CHINA Abstract This article examines the troubled relationship between Tibetan Buddhism and the Chinese state since 1949. In the history of this relationship, a cyclical pattern of Chinese attempts, both violently assimilative and subtly corrosive, to control Tibetan Buddhism and a multifaceted Tibetan resistance to defend their religious heritage, will be revealed. This article will develop a security-based logic for that cyclical dynamic. For these purposes, a two-level analytical framework will be applied. First, the framework of the insecurity dilemma will be used to draw the broad outlines of the historical cycles of repression and resistance. However, the insecurity dilemma does not look inside the concept of security and it is not helpful to establish how Tibetan Buddhism became a security issue in the first place and continues to retain that status. The theory of securitisation is best suited to perform this analytical task. As such, the cycles of Chinese repression and Tibetan resistance fundamentally originate from the incessant securitisation of Tibetan Buddhism by the Chinese state and its apparatchiks. The paper also considers the why, how, and who of this securitisation, setting the stage for a future research project taking up the analytical effort to study the why, how and who of a potential desecuritisation of all things Tibetan, including Tibetan Buddhism, and its benefits for resolving the protracted Sino- Tibetan conflict. -

Recounting the Fifth Dalai Lama's Rebirth Lineage

Recounting the Fifth Dalai Lama’s Rebirth Lineage Nancy G. Lin1 (Vanderbilt University) Faced with something immensely large or unknown, of which we still do not know enough or of which we shall never know, the author proposes a list as a specimen, example, or indication, leaving the reader to imagine the rest. —Umberto Eco, The Infinity of Lists2 ncarnation lineages naming the past lives of eminent lamas have circulated since the twelfth century, that is, roughly I around the same time that the practice of identifying reincarnating Tibetan lamas, or tulkus (sprul sku), began.3 From the twelfth through eighteenth centuries it appears that incarnation or rebirth lineages (sku phreng, ’khrungs rabs, etc.) of eminent lamas rarely exceeded twenty members as presented in such sources as their auto/biographies, supplication prayers, and portraits; Dölpopa Sherab Gyeltsen (Dol po pa Shes rab rgyal mtshan, 1292–1361), one such exception, had thirty-two. Among other eminent lamas who traced their previous lives to the distant Indic past, the lineages of Nyangrel Nyima Özer (Nyang ral Nyi ma ’od zer, 1124–1192) had up 1 I thank the organizers and participants of the USF Symposium on The Tulku Institution in Tibetan Buddhism, where this paper originated, along with those of the Harvard Buddhist Studies Forum—especially José Cabezón, Jake Dalton, Michael Sheehy, and Nicole Willock for the feedback and resources they shared. I am further indebted to Tony K. Stewart, Anand Taneja, Bryan Lowe, Dianna Bell, and Rae Erin Dachille for comments on drafted materials. I thank the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange for their generous support during the final stages of revision.