Tavera Exhibit Booklet.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Southern Denmark

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN DENMARK THE CHRISTIAN KINGDOM AS AN IMAGE OF THE HEAVENLY KINGDOM ACCORDING TO ST. BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY INSTITUTE OF HISTORY, CULTURE AND CIVILISATION CENTRE FOR MEDIEVAL STUDIES BY EMILIA ŻOCHOWSKA ODENSE FEBRUARY 2010 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In my work, I had the privilege to be guided by three distinguished scholars: Professor Jacek Salij in Warsaw, and Professors Tore Nyberg and Kurt Villads Jensen in Odense. It is a pleasure to admit that this study would never been completed without the generous instruction and guidance of my masters. Professor Salij introduced me to the world of ancient and medieval theology and taught me the rules of scholarly work. Finally, he encouraged me to search for a new research environment where I could develop my skills. I found this environment in Odense, where Professor Nyberg kindly accepted me as his student and shared his vast knowledge with me. Studying with Professor Nyberg has been a great intellectual adventure and a pleasure. Moreover, I never would have been able to work at the University of Southern Denmark if not for my main supervisor, Kurt Villads Jensen, who trusted me and decided to give me the opportunity to study under his kind tutorial, for which I am exceedingly grateful. The trust and inspiration I received from him encouraged me to work and in fact made this study possible. Karen Fogh Rasmussen, the secretary of the Centre of Medieval Studies, had been the good spirit behind my work. -

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States Winthrop D. Jordan1 Edited by Paul Spickard2 Editor’s Note Winthrop Jordan was one of the most honored US historians of the second half of the twentieth century. His subjects were race, gender, sex, slavery, and religion, and he wrote almost exclusively about the early centuries of American history. One of his first published articles, “American Chiaroscuro: The Status and Definition of Mulattoes in the British Colonies” (1962), may be considered an intellectual forerunner of multiracial studies, as it described the high degree of social and sexual mixing that occurred in the early centuries between Africans and Europeans in what later became the United States, and hinted at the subtle racial positionings of mixed people in those years.3 Jordan’s first book, White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550–1812, was published in 1968 at the height of the Civil Rights Movement era. The product of years of painstaking archival research, attentive to the nuances of the thousands of documents that are its sources, and written in sparkling prose, White over Black showed as no previous book had done the subtle psycho-social origins of the American racial caste system.4 It won the National Book Award, the Ralph Waldo Emerson Prize, the Bancroft Prize, the Parkman Prize, and other honors. It has never been out of print since, and it remains a staple of the graduate school curriculum for American historians and scholars of ethnic studies. In 2005, the eminent public intellectual Gerald Early, at the request of the African American magazine American Legacy, listed what he believed to be the ten most influential books on African American history. -

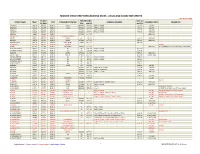

Residential Resurfacing List

MISSION VIEJO STREET RESURFACING INDEX - LOCAL AND COLLECTOR STREETS Rev. DEC 31, 2020 TB MAP RESURFACING LAST AC STREET NAME TRACT TYPE COMMUNITY/OWNER ADDRESS NUMBERS PAVEMENT INFO COMMENTS PG GRID TYPE MO/YR MO/YR ABADEJO 09019 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 28241 to 27881 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABADEJO 09018 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 27762 to 27832 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABANICO 09566 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27551 to 27581 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABANICO 09568 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27541 to 27421 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABEDUL 09563 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 .35AC/NS ABERDEEN 12395 922 C7 PRIVATE HIGHLAND CONDOS -- ABETO 08732 892 D5 PUBLIC MVEA AC JUL 15 JUL 15 .35AC/NS ABRAZO 09576 892 D3 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ACACIA COURT 08570 891 J6 PUBLIC TIMBERLINE TRMSS OCT 14 AUG 08 ACAPULCO 12630 892 F1 PRIVATE PALMIA -- GATED ACERO 79-142 892 A6 PUBLIC HIGHPARK TRMSS OCT 14 .55AC/NS 4/1/17 TRMSS 40' S of MAQUINA to ALAMBRE ACROPOLIS DRIVE 06667 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24582 to 24781 AUG 08 ACROPOLIS DRIVE 07675 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24801 to 24861 AUG 08 ADELITA 09078 892 D4 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ADOBE LANE 06325 922 C1 PUBLIC MVSRC RPMSS OCT 17 AUG 08 .17SAC/.58AB ADONIS STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24161 to 24232 SEP 14 ADONIS STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24101 to 24152 SEP 14 ADRIANA STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AEGEA STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AGRADO 09025 922 D1 PUBLIC OVGA AC AUG 18 AUG 18 .4AC/NS AGUILAR 09255 892 D1 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 PINAVETE -

DOWNLOAD Primerang Bituin

A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim Copyright 2006 Volume VI · Number 1 15 May · 2006 Special Issue: PHILIPPINE STUDIES AND THE CENTENNIAL OF THE DIASPORA Editors Joaquin Gonzalez John Nelson Philippine Studies and the Centennial of the Diaspora: An Introduction Graduate Student >>......Joaquin L. Gonzalez III and Evelyn I. Rodriguez 1 Editor Patricia Moras Primerang Bituin: Philippines-Mexico Relations at the Dawn of the Pacific Rim Century >>........................................................Evelyn I. Rodriguez 4 Editorial Consultants Barbara K. Bundy Hartmut Fischer Mail-Order Brides: A Closer Look at U.S. & Philippine Relations Patrick L. Hatcher >>..................................................Marie Lorraine Mallare 13 Richard J. Kozicki Stephen Uhalley, Jr. Apathy to Activism through Filipino American Churches Xiaoxin Wu >>....Claudine del Rosario and Joaquin L. Gonzalez III 21 Editorial Board Yoko Arisaka The Quest for Power: The Military in Philippine Politics, 1965-2002 Bih-hsya Hsieh >>........................................................Erwin S. Fernandez 38 Uldis Kruze Man-lui Lau Mark Mir Corporate-Community Engagement in Upland Cebu City, Philippines Noriko Nagata >>........................................................Francisco A. Magno 48 Stephen Roddy Kyoko Suda Worlds in Collision Bruce Wydick >>...................................Carlos Villa and Andrew Venell 56 Poems from Diaspora >>..................................................................Rofel G. Brion -

The Art of Conversation: Eighteenth-Century Mexican Casta Painting

Graduate Journal of Visual and Material Culture Issue 5 I 2012 The Art of Conversation: Eighteenth-Century Mexican Casta Painting Mey-Yen Moriuchi ______________________________________________ Abstract: Traditionally, casta paintings have been interpreted as an isolated colonial Mexican art form and examined within the social historical moment in which they emerged. Casta paintings visually represented the miscegenation of the Spanish, Indian and Black African populations that constituted the new world and embraced a diverse terminology to demarcate the land’s mixed races. Racial mixing challenged established social and racial categories, and casta paintings sought to stabilize issues of race, gender and social status that were present in colonial Mexico. Concurrently, halfway across the world, another country’s artists were striving to find the visual vocabulary to represent its families, socio-economic class and genealogical lineage. I am referring to England and its eighteenth-century conversation pictures. Like casta paintings, English conversation pieces articulate beliefs about social and familial propriety. It is through the family unit and the presence of a child that a genealogical statement is made and an effigy is preserved for subsequent generations. Utilizing both invention and mimesis, artists of both genres emphasize costume and accessories in order to cater to particular stereotypes. I read casta paintings as conversations like their European counterparts—both internal conversations among the figures within the frame, and external ones between the figures, the artist and the beholder. It is my position that both casta paintings and conversation pieces demonstrate a similar concern with the construction of a particular self-image in the midst of societies that were apprehensive about the varying conflicting notions of socio-familial and socio-racial categories. -

![Genetic Divergence and Polyphyly in the Octocoral Genus Swiftia [Cnidaria: Octocorallia], Including a Species Impacted by the DWH Oil Spill](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9917/genetic-divergence-and-polyphyly-in-the-octocoral-genus-swiftia-cnidaria-octocorallia-including-a-species-impacted-by-the-dwh-oil-spill-739917.webp)

Genetic Divergence and Polyphyly in the Octocoral Genus Swiftia [Cnidaria: Octocorallia], Including a Species Impacted by the DWH Oil Spill

diversity Article Genetic Divergence and Polyphyly in the Octocoral Genus Swiftia [Cnidaria: Octocorallia], Including a Species Impacted by the DWH Oil Spill Janessy Frometa 1,2,* , Peter J. Etnoyer 2, Andrea M. Quattrini 3, Santiago Herrera 4 and Thomas W. Greig 2 1 CSS Dynamac, Inc., 10301 Democracy Lane, Suite 300, Fairfax, VA 22030, USA 2 Hollings Marine Laboratory, NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Sciences, National Ocean Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 331 Fort Johnson Rd, Charleston, SC 29412, USA; [email protected] (P.J.E.); [email protected] (T.W.G.) 3 Department of Invertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 10th and Constitution Ave NW, Washington, DC 20560, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Biological Sciences, Lehigh University, 111 Research Dr, Bethlehem, PA 18015, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Mesophotic coral ecosystems (MCEs) are recognized around the world as diverse and ecologically important habitats. In the northern Gulf of Mexico (GoMx), MCEs are rocky reefs with abundant black corals and octocorals, including the species Swiftia exserta. Surveys following the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill in 2010 revealed significant injury to these and other species, the restoration of which requires an in-depth understanding of the biology, ecology, and genetic diversity of each species. To support a larger population connectivity study of impacted octocorals in the Citation: Frometa, J.; Etnoyer, P.J.; GoMx, this study combined sequences of mtMutS and nuclear 28S rDNA to confirm the identity Quattrini, A.M.; Herrera, S.; Greig, Swiftia T.W. -

Vulgaris Seu Universalis

Paolo Aranha Vulgaris seu Universalis Early Modern Missionary Representations of an Indian Cosmopolitan Space Early Modern Oriental Knowledge and Missionary Debates in India The history of religious missions, in particular the early modern European Catholic ones, has drawn a remarkable interest in recent years, both among scholars and by the general public.1 Such a trend can be explained by several reasons, although all of them seem to be related to the processes of globali- zation or mondialisation that are seen at work with special intensity in our time. The religious missions are indeed a phenomenon that exemplifies in an eloquent way the intellectual exercise of a global history aiming to find connections and exchanges, both material and cultural, among different parts of the world. Missionaries can be seen also as professional brokers of cultural diversity, evoking just too easily—and not necessarily in a very pertinent way—current debates on multiculturalism and encounters of cultures. More- over, European religious missions are an obvious benchmark for endorsing or criticising the category of “Orientalism,” as developed—both influentially and controversially—by Edward Said (1978). As religious missions draw a growing attention, it has been recently suggested that these might be considered less predominantlySpecimen than in the past in terms of a religious specificity. Pierre- Antoine Fabre and Bernard Vincent claimed in the introduction to a recent collective book that the historiography on early modern missions has been developed lately in function of “a research horizon independent from the traditions connected to religious history.”2 Such an observation seems to be confirmed in the case of the Jesuits, the single most studied religious order of early modern Catholicism, to the point that “currently, in danger of being lost sight of is precisely the religious dimension of the Jesuit enterprise” (O’Malley 2013: 33). -

Re-Indigenizing Spaces: How Mapping Racial Violence Shows the Interconnections Between

“Re-Indigenizing Spaces: How Mapping Racial Violence Shows the Interconnections Between Settler Colonialism and Gentrification” By Jocelyn Lopez Senior Honors Thesis for the Ethnic Studies Department College of Letters and Sciences Of the University of California, Berkeley Thesis Advisor: Professor Beth Piatote Spring 2020 Lopez, 2 Introduction Where does one begin when searching for the beginning of the city of Inglewood? Siri, where does the history of Inglewood, CA begin? Siri takes me straight to the City History section of the City of Inglewood’s website page. Their website states that Inglewood’s history begins in the Adobe Centinela, the proclaimed “first home” of the Rancho Aguaje de la Centinela which housed Ignacio Machado, the Spanish owner of the rancho who was deeded the adobe in 1844. Before Ignacio, it is said that the Adobe Centinela served as a headquarters for Spanish soldiers who’d protect the cattle and springs. But from whom? Bandits or squatters are usually the go to answers. If you read further into the City History section, Inglewood only recognizes its Spanish and Mexican past. But where is the Indigenous Tongva-Gabrielino history of Inglewood? I have lived in Inglewood all of my life. I was born at Centinela Hospital Medical Center on Hardy Street in 1997. My entire K-12 education came from schools under the Inglewood Unified School District. While I attend UC Berkeley, my family still lives in Inglewood in the same house we’ve lived in for the last 23 years. Growing up in Inglewood, in a low income, immigrant family I witnessed things in my neighborhood that not everyone gets to see. -

From Casta to Costumbrismo: Representations of Racialized Social Spaces Mey-Yen Moriuchi

chapter 7 From Casta to Costumbrismo: Representations of Racialized Social Spaces Mey-Yen Moriuchi In colonial Mexico, the miscegenation1 of indigenous, African, and European populations resulted in a plethora of diverse genetic mixings that challenged racial and ethnic purity and disrupted social stability. The visual arts played a critical role in illustrating to contemporary viewers how to understand race scientifically and culturally. In turn, they also fostered racial stereotypes that proliferated into the nineteenth century. These stereotypes can be seen most readily in secular paintings, such as the casta and costumbrista genres, where depictions of everyday people and their daily lives were the primary subject matter. This chapter will explore the resonances between eighteenth-century casta and nineteenth-century costumbrista imagery. In the same way that a string on a musical instrument will begin to vibrate, or ‘resonate,’ when a string tuned to the same frequency upon another instrument is played, there exist important indirect resonances beyond the direct interactions between these two genres. Both the direct interactions and indirect resonances capture the visibility and invisibility of race and miscegenation. I will examine the racial- ized social spaces, that is, spatial representations of racial and social rela- tionships, in eighteenth-century casta and nineteenth-century costumbrista painting. We can find, from casta to costumbrista paintings, a continuity of aesthetic and stylistic conventions as well as underlying preoccupations with socio-racial and socio-familial relationships, a subject that has largely gone unexamined thus far in scholarship of Mexican visual culture.2 1 A mixture of races. The term was coined in 1864 and comes from the Latin words miscere (to mix) and genus (race). -

Five Casta Paintings by Buenaventura José Guiol, a New Discovery

Ana Zabía de la Mata FIVE CASTA PAINTINGS BY BUENAVENTURA JOSÉ GUIOL, A NEW DISCOVERY Number 4 Five Casta Paintings by Buenaventura José Guiol A New Discovery Publisher Jaime Eguiguren Author Ana Zabía de la Mata Photography Joaquín Cortés Noriega Román Lores Riesgo Project Coordinator Sofía Fernández Lázaro FIVE Translation Edward Ewing CASTA Design and Layout Laura Eguiluz de la Rica PAINTINGS Printing & Binding BY Jiménez Godoy BUENAVENTURA JOSÉ GUIOL, Special thanks Clara E. Aranda Ruiz A NEW Colección Phelps de Cisneros Denver Art Museum DISCOVERY Encarnación Hidalgo Cámara Fernando Rayon Francis X. Rocca Tomás González Sada Hugo Armando Felix Rocha Jorge Rivas La Troupe Luis Fontes de Albornoz Mirta Insaurralde Caballero Museo de América Museo Regional Michoacano Ana Zabía de la Mata Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Vivian Velar de Irigoyen ISBN: 978-84-09-05068-0 © 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any storage and retrieval system, without the prior permission in writing from the publisher. FIVE CASTA PAINTINGS BY BUENAVENTURA JOSÉ GUIOL, A NEW DISCOVERY FOREWORD When referring to the castas, we are transported to Hispanic-American society: more precisely, to that of 18th Century Mexico. Through these series, which have lasted over time, we can observe with some certainty, the intermingling and coexistence of different types of races that produced new lineages defined by specific names. The descendants of these mixed races formed the various castas. While the Spaniards in Hispanic America were, of course, those of the highest social rank, their spirit, often kind and amorous, did not prevent them from mixing and having children with Native American Indians, blacks and mestizas. -

The Presence of Africa in the Caribbean, the Antilles and the United States Other Books in the Research and Ideas Series

RESEARCH AND IDEAS SERIES History The Presence of Africa in the Caribbean, www.gfddpublications.org - www.globalfoundationdd.org - www.funglode.org the Antilles and the United States Celsa Albert Batista - Patrick Bellegarde-Smith - Delia Blanco - Lipe Collado RESEARCH AND IDEAS SERIES Franklin Franco - Jean Ghasmann Bissainthe - José Guerrero - Rafael Jarvis Luis Education Mateo Morrison - Melina Pappademos - Odalís G. Pérez - Geo Ripley Health José Luis Sáez - Avelino Stanley - Dario Solano - Roger Toumson Urban Development History THE PRESENCE OF AFRICA IN THE CARIBBEAN, THE ANTILLES AND THE UNITED StatES Other books in the Research and Ideas Series: Distance Education and Challenges by Heitor Gurgulino de Souza El Metro and the Impacts of Transportation System Integration in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic by Carl Allen The Presence of Africa in the Caribbean, the Antilles and the United States Celsa Albert Batista Patrick Bellegarde-Smith Delia Blanco Lipe Collado Franklin Franco Jean Ghasmann Bissainthe José Guerrero Rafael Jarvis Luis Mateo Morrison Melina Pappademos Odalís G. Pérez Geo Ripley José Luis Sáez Avelino Stanley Dario Solano Roger Toumson RESEARCH AND IDEAS SERIES History This is a publication of gfdd and funglode Global Foundation for Democracy and Development www.globalfoundationdd.org Fundación Global Democracia y Desarrollo www.funglode.org The Presence of Africa in the Caribbean, the Antilles and the United States Copyright @ 2012 by GFDD-FUNGLODE All rights Reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. ISBN: 978-9945-412-74-1 Printed by World Press in the USA Editor-in-Chief Graphic Design Natasha Despotovic Maria Montas Marta Massano Supervising Editor Semiramis de Miranda Collaborators Yamile Eusebio Style Editor Asunción Sanz Kerry Stefancyk Translator Maureen Meehan www.gfddpublications.org Table of Contents Foreword ............................................................................ -

Seventeenth-Century Spanish Colonial Identity in New Mexico: a Study of Identity Practices Through Material Culture

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Anthropology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 11-15-2019 Seventeenth-Century Spanish Colonial Identity in New Mexico: A Study of Identity Practices through Material Culture Caroline M. Gabe University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/anth_etds Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Chicana/o Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, Latin American History Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Gabe, Caroline M.. "Seventeenth-Century Spanish Colonial Identity in New Mexico: A Study of Identity Practices through Material Culture." (2019). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/anth_etds/184 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Caroline Marie Gabe Candidate Anthropology Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Emily Lena Jones , Co-Chairperson Dr. Frances Hayashida , Co-Chairperson Dr. Bruce B. Huckell Prof. Christopher Wilson i SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY SPANISH COLONIAL IDENTITY IN NEW MEXICO: A STUDY