Re-Indigenizing Spaces: How Mapping Racial Violence Shows the Interconnections Between

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blacks and Asians in Mississippi Masala, Barriers to Coalition Building

Both Edges of the Margin: Blacks and Asians in Mississippi Masala, Barriers to Coalition Building Taunya Lovell Bankst Asians often take the middle position between White privilege and Black subordination and therefore participate in what Professor Banks calls "simultaneous racism," where one racially subordinatedgroup subordi- nates another. She observes that the experience of Asian Indian immi- grants in Mira Nair's film parallels a much earlier Chinese immigrant experience in Mississippi, indicatinga pattern of how the dominantpower uses law to enforce insularityamong and thereby control different groups in a pluralistic society. However, Banks argues that the mere existence of such legal constraintsdoes not excuse the behavior of White appeasement or group insularityamong both Asians and Blacks. Instead,she makes an appealfor engaging in the difficult task of coalition-buildingon political, economic, socialand personallevels among minority groups. "When races come together, as in the present age, it should not be merely the gathering of a crowd; there must be a bond of relation, or they will collide...." -Rabindranath Tagore1 "When spiders unite, they can tie up a lion." -Ethiopian proverb I. INTRODUCTION In the 1870s, White land owners recruited poor laborers from Sze Yap or the Four Counties districts in China to work on plantations in the Mis- sissippi Delta, marking the formal entry of Asians2 into Mississippi's black © 1998 Asian Law Journal, Inc. I Jacob A. France Professor of Equality Jurisprudence, University of Maryland School of Law. The author thanks Muriel Morisey, Maxwell Chibundu, and Frank Wu for their suggestions and comments on earlier drafts of this Article. 1. -

University of Southern Denmark

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN DENMARK THE CHRISTIAN KINGDOM AS AN IMAGE OF THE HEAVENLY KINGDOM ACCORDING TO ST. BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY INSTITUTE OF HISTORY, CULTURE AND CIVILISATION CENTRE FOR MEDIEVAL STUDIES BY EMILIA ŻOCHOWSKA ODENSE FEBRUARY 2010 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In my work, I had the privilege to be guided by three distinguished scholars: Professor Jacek Salij in Warsaw, and Professors Tore Nyberg and Kurt Villads Jensen in Odense. It is a pleasure to admit that this study would never been completed without the generous instruction and guidance of my masters. Professor Salij introduced me to the world of ancient and medieval theology and taught me the rules of scholarly work. Finally, he encouraged me to search for a new research environment where I could develop my skills. I found this environment in Odense, where Professor Nyberg kindly accepted me as his student and shared his vast knowledge with me. Studying with Professor Nyberg has been a great intellectual adventure and a pleasure. Moreover, I never would have been able to work at the University of Southern Denmark if not for my main supervisor, Kurt Villads Jensen, who trusted me and decided to give me the opportunity to study under his kind tutorial, for which I am exceedingly grateful. The trust and inspiration I received from him encouraged me to work and in fact made this study possible. Karen Fogh Rasmussen, the secretary of the Centre of Medieval Studies, had been the good spirit behind my work. -

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States Winthrop D. Jordan1 Edited by Paul Spickard2 Editor’s Note Winthrop Jordan was one of the most honored US historians of the second half of the twentieth century. His subjects were race, gender, sex, slavery, and religion, and he wrote almost exclusively about the early centuries of American history. One of his first published articles, “American Chiaroscuro: The Status and Definition of Mulattoes in the British Colonies” (1962), may be considered an intellectual forerunner of multiracial studies, as it described the high degree of social and sexual mixing that occurred in the early centuries between Africans and Europeans in what later became the United States, and hinted at the subtle racial positionings of mixed people in those years.3 Jordan’s first book, White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550–1812, was published in 1968 at the height of the Civil Rights Movement era. The product of years of painstaking archival research, attentive to the nuances of the thousands of documents that are its sources, and written in sparkling prose, White over Black showed as no previous book had done the subtle psycho-social origins of the American racial caste system.4 It won the National Book Award, the Ralph Waldo Emerson Prize, the Bancroft Prize, the Parkman Prize, and other honors. It has never been out of print since, and it remains a staple of the graduate school curriculum for American historians and scholars of ethnic studies. In 2005, the eminent public intellectual Gerald Early, at the request of the African American magazine American Legacy, listed what he believed to be the ten most influential books on African American history. -

Survey of Quercus Kelloggii at Pepperwood Preserve: Identifying Specimen Oaks to Reimplement Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Promote Ecosystem Resilience

Survey of Quercus kelloggii at Pepperwood Preserve: identifying specimen oaks to reimplement traditional ecological knowledge and promote ecosystem resilience by Cory James O’Gorman A thesis submitted to Sonoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Biology Committee Members: Dr. Lisa Bentley Dr. Daniel Crocker Dr. Margaret Purser 4/21/2020 i Copyright 2020 By Cory J. O’Gorman ii Authorization for Reproduction of Master’s Thesis I grant permission for the print or digital reproduction of this thesis in its entirety, without further authorization from me, on the condition that the person or agency requesting reproduction absorb the cost and provide proper acknowledgment of authorship. DATE: ___5/4/2020_______________ ________Cory J. O’Gorman_______ Name iii Survey of Quercus kelloggii at Pepperwood Preserve: identifying specimen oaks to reimplement traditional ecological knowledge and promote ecosystem resilience Thesis by Cory James O’Gorman Abstract Purpose of the Study: California black oak, Quercus kelloggii, plays an important role in the lifeways of many indigenous tribes throughout California. Native peoples tend black oaks using Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) to encourage the development and proliferation of specimen oaks. These mature, large, full crowned trees provide a disproportionate amount of ecosystem services, including acorns and habitat, when compared to smaller black oaks. Altered approaches to land management and the cessation of frequent low intensity cultural burns places these specimen oaks at risk from encroachment, forest densification, and catastrophic fire. Procedure: This project is a collaboration between Sonoma State University and the Native Advisory Council of Pepperwood Preserve. -

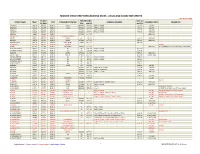

Residential Resurfacing List

MISSION VIEJO STREET RESURFACING INDEX - LOCAL AND COLLECTOR STREETS Rev. DEC 31, 2020 TB MAP RESURFACING LAST AC STREET NAME TRACT TYPE COMMUNITY/OWNER ADDRESS NUMBERS PAVEMENT INFO COMMENTS PG GRID TYPE MO/YR MO/YR ABADEJO 09019 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 28241 to 27881 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABADEJO 09018 892 E7 PUBLIC OVGA RPMSS1 OCT 18 27762 to 27832 JUL 04 .4AC/NS ABANICO 09566 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27551 to 27581 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABANICO 09568 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 27541 to 27421 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ABEDUL 09563 892 D2 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 .35AC/NS ABERDEEN 12395 922 C7 PRIVATE HIGHLAND CONDOS -- ABETO 08732 892 D5 PUBLIC MVEA AC JUL 15 JUL 15 .35AC/NS ABRAZO 09576 892 D3 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ACACIA COURT 08570 891 J6 PUBLIC TIMBERLINE TRMSS OCT 14 AUG 08 ACAPULCO 12630 892 F1 PRIVATE PALMIA -- GATED ACERO 79-142 892 A6 PUBLIC HIGHPARK TRMSS OCT 14 .55AC/NS 4/1/17 TRMSS 40' S of MAQUINA to ALAMBRE ACROPOLIS DRIVE 06667 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24582 to 24781 AUG 08 ACROPOLIS DRIVE 07675 922 A1 PUBLIC AH AC AUG 08 24801 to 24861 AUG 08 ADELITA 09078 892 D4 PUBLIC MVEA RPMSS OCT 17 SEP 10 .35AC/NS ADOBE LANE 06325 922 C1 PUBLIC MVSRC RPMSS OCT 17 AUG 08 .17SAC/.58AB ADONIS STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24161 to 24232 SEP 14 ADONIS STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 24101 to 24152 SEP 14 ADRIANA STREET 06092 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AEGEA STREET 06093 891 J7 PUBLIC AH AC SEP 14 SEP 14 AGRADO 09025 922 D1 PUBLIC OVGA AC AUG 18 AUG 18 .4AC/NS AGUILAR 09255 892 D1 PUBLIC RPMSS OCT 17 PINAVETE -

Sustainable Burbank Commission City of Burbank Boards, Commissions & Committees Submit Date: May 03, 2021 Application Form

Sustainable Burbank Commission City of Burbank Boards, Commissions & Committees Submit Date: May 03, 2021 Application Form Profile Elliot A Gannon Prefix First Name Middle Initial Last Name Email Address N Hollywood Way Home Address Suite or Apt Burbank CA 91505 City State Postal Code Mobile: Primary Phone Alternate Phone Director’s Guild of America Assistant Director 2nd AD Employer Job Title Occupation Which Boards would you like to apply for? Police Commission: Submitted Sustainable Burbank Commission: Submitted Length of time as a Burbank Resident: 15 years Burbank Registered Voter? Yes No Interests & Experiences Please tell us about yourself and why you want to serve. Why are you interested in serving on a board, commission or committee? I love Burbank and desire to be a part of it’s continual improvement. Education Palos Verdes Peninsula High School Dell Arte International School of Physical Theatre Additional Pertinent Courses or Training I’ve spent over twenty years working in theatre and film production Elliot A Gannon Other Pertinent Skills, Experience or Interests I’m very active in community outreach, easily approachable, and a natural leader. Upload a Resume Community Involvement Specify current or prior service on a City Board, Commission or Committee: N/A List Community activities in which you are involved: I’ve been active with the Burbank Arts Festival several times over the last decade. I volunteer as a member of Media City Church with different outreaches in the county. Very active on the ground with community outreach. If you are related to any City of Burbank employee(s), please state their name(s), relationship(s), and department(s). -

AVIATION/96TH STREET FIRST/LAST MILE PLAN APPENDIX Appendix a Walk Audit Summary Inglewood First/Last Mile Existing Conditions Overview Map

Next stop: our healthy future. /96 / 3/22/19 Draft Inglewood First/Last Mile Strategic Plan A Los Angeles Metro Jacob Lieb, First/Last Mile Planning My La, First/Last Mile Planning Joanna Chan, First/Last Mile Planning Los Angeles World Airports Glenda Silva, External Affairs Department Consultants Shannon Davis, Here LA Amber Hawkes, Here LA Chad So, Here LA Aryeh Cohen, Here LA Mary Reimer, Steer Craig Nelson, Steer Peter Piet, Steer Christine Robert, The Robert Group Nicole Ross, The Robert Group B Aviation/96th St. First/Last Mile Plan Contents D Executive Summary 22 Recommendations 1 Overview 23 Pathways & Projects 26 Aviation / 96th St. Station 2 Introduction 3 Introduction 40 Next Steps 4 What is First/Last Mile? 41 Introduction 5 Vision 42 Lessons Learned 6 Planning for Changes 43 Looking Forward 8 Terminology Appendix 10 Introducing the A Walk Audit Summary Station Area B Existing Plans & Projects Memo 11 First/Last Mile Planning Around C Pathway Origin Matrix the Station D Costing Assumptions / Details 12 Aviation / 96th St. Station E Funding Strategies & Funding Sources 14 Process 15 Formulating the Plan 16 Phases Aviation/96th St. First/Last Mile Plan C EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This section introduces the Aviation/96 St. Station first/last mile project, and lists the key findings and recommendations that are within the Plan. D Aviation/96th St. First/Last Mile Plan Overview of the Plan The Aviation/96th St. First/Last (where feasible) separation from Next Steps Mile Plan is part of an ongoing vehicular traffic This short chapter describes effort to increase the accessibility, > More lighting for people walking, the next steps after Metro safety, and comfort of the area biking, or otherwise ‘rolling’ to Board adoption, focusing on surrounding the future LAX/Metro the station at night implementation. -

Xenophobia, Nativism and Pan-Africanism in 21St Century Africa

H-Africa Xenophobia, Nativism and Pan-Africanism in 21st Century Africa Document published by Sabella Abidde on Wednesday, June 17, 2020 cfp-2-xenophobianativismpanafricanism.pdf cfp-2-xenophobianativismpanafricanism.pdf Description: CALL FOR BOOK CHAPTERS Xenophobia, Nativism and Pan-Africanism in 21st Century Africa Sabella Abidde and Emmanuel Matambo (Editors) The purpose of this project is to examine the mounting incidence of xenophobia and nativism across the African continent. Second, it seeks to examine how invidious and self-immolating xenophobia and nativism negate the noble intent of Pan-Africanism. Finally, it aims to examine the implications of the resentments, the physical and mental attacks, and the incessant killings on the psyche, solidarity, and development of the Black World. According to Michael W. Williams, Pan-Africanism is the cooperative movement among peoples of African origin to unite their efforts in the struggle to liberate Africa and its scattered and suffering people; to liberate them from the oppression and exploitation associated with Western hegemony and the international expansionism of the capitalist system. Xenophobia, on the other hand, is the loathing or fear of foreigners with a violent component in the form of periodic attacks and extrajudicial killings committed mostly by native-born citizens. Nativism is the policy and or laws designed to protect the interests of native-born citizens or established residents. The project intends to argue that xenophobia and nativism negate the intent, aspiration, and spirit of Pan-Africanism as expressed by early proponents such as Edward Blyden, W.E.B. Du Bois, C.L.R. James, George Padmore, Léopold Senghor, Jomo Kenyatta, Aimé Césaire, and Kwame Nkrumah. -

K. Garrison Clarke Collection of Photographs of Southern California and Baja California, Mexico 0322

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt8n39s2f8 No online items The Finding Aid of the K. Garrison Clarke collection of photographs of Southern California and Baja California, Mexico 0322 Finding aid prepared by Katie Richardson The processing of this collection and the creation of this finding aid was funded by the generous support of the Council on Library and Information Resources. First edition USC Libraries Special Collections Doheny Memorial Library 206 3550 Trousdale Parkway Los Angeles, California, 90089-0189 213-740-5900 [email protected] October 2010 The Finding Aid of the K. Garrison 0322 1 Clarke collection of photographs of Southern California and Baja ... Title: K. Garrison Clarke collection of photographs of Southern California and Baja California, Mexico Collection number: 0322 Contributing Institution: USC Libraries Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 128.0 Items1 box Date (inclusive): 1948-1975 Abstract: The collection consists of 128 black and white reprints of images taken by K. Garrison Clarke between 1948 and 1975. Most of the images are taken in and around Los Angeles County. A sizable amount of photographs are from a 1961 photo shoot at Jungleland USA, an animal training center in Thousand Oaks, CA that housed animals used in Hollywood films. Images from a commercial experiment at Oxnard and the Channel Islands (1965) and photographs from a shoot for Mexico West Coast Magazine in Baja California (1965) are also included. creator: Clarke, Kenrow Garrison, 1931- Conditions Governing Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE. Advance notice required for access. Arrangement Original order and original series designation were maintained with the Clarke Collection. -

5. Environmental Analysis

5. Environmental Analysis 5.1 CULTURAL RESOURCES Cultural resources include places, object, structures, and settlements that reflect group or individual religious, archaeological, architectural, or paleontological activities, or are considered important for their architectural or historical value. Such resources provide information on scientific progress, environmental adaptations, group ideology, or other human advancements. This section of the Draft Environmental Impact Report (DEIR) evaluates the potential for implementation of the San Marino High School Michael White Adobe project to impact cultural resources in the City of San Marino. The analysis in this section is based, in part, upon the following information: • Michael White Adobe Historic Resources Technical Report, Chattel Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, August 4, 2009. This study is included in Appendix D of this Draft EIR. 5.1.1 Regulatory Background National Historic Preservation Act Section 106 (Protection of Historic Properties) of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (NHPA) requires federal agencies to take into account the effects of their undertakings on historic properties. Section 106 Review refers to the federal review process designed to ensure that historic properties are considered during federal project planning and implementation. The Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, an independent federal agency, administers the review process, with assistance from State Historic Preservation Offices. National Register of Historic Resources (National Register) The National Register is the nation’s official list of historic and cultural resources worthy of preservation. Authorized under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, the National Register is part of a national program to coordinate and support public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect the country’s historic and archaeological resources. -

28Th Annual California Indian Conference and Gathering

California Indian Conference andGathering Indian Conference California October 3-5,2013 “Honor Our Past, Celebrate Our Present, and and OurPresent, Celebrate “Honor OurPast, Nurture Our Future Generations” OurFuture Nurture 28TH ANNUAL | California State University, Sacramento University, State California PAINTINGPAINTING BY LYNL RISLING (KARUK, (KARUK YUROKYUROK, AND HUPA) “TÁAT KARU YUPSÍITANACH” (REPRESENTS A MOTHER AND BABY FROM TRIBES OF NORTHWES NORTHWESTERNTERN CALIFORNIA) letter from the Planning Committee Welcome to the 28th Annual California Indian Conference and Gathering We are honored to have you attending and participating in this conference. Many people, organizations and Nations have worked hard and contributed in various ways. It makes us feel good in our hearts to welcome each and every person. We come together to learn from each other and enjoy seeing long-time friends, as well as, meeting new ones. The California Indian Conference and Gathering is an annual event for the exchange of views and Information among academics, educators, California Indians, students, tribal nations, native organizations and community members focusing on California Indians. This year, the conference is held at California State University, Sacramento. Indians and non-Indians will join together to become aware of current issues, as well as the history and culture of the first peoples of this state. A wide variety of Front cover: topics will be presented, including: sovereignty, leadership, dance, storytelling, The painting is titled, “Taat karu native languages, histories, law, political and social issues, federal recognition, Yupsíitanach” (Mother and Baby). The health, families and children, education, economic development, arts, traditions painting represents a mother and and numerous other relevant topics. -

3.5 Geology/Soils

3.5 GEOLOGY/SOILS 3.5.1 INTRODUCTION This section describes the project’s impacts related to geology and soils, including such factors as seismology, soils, topography, and erosion. It also includes an examination of potential hazards associated with potential damage to proposed structures and infrastructure from ground shaking, potential liquefaction hazards and soils and soils stability. Applicable laws, regulations and relevant local planning policies that pertain to geology are also discussed. Much of the information contained in this subsection was based upon the following geotechnical reports submitted by consultants under contract to the Chandler’s Palos Verdes Sand and Gravel Company and the peer review of those technical studies by Arroyo/Willdan Geotechnical: Geologic Constraints Investigation of the Chandler’s Inert Solid Land Fill Quarry and Surrounding Properties, Rolling Hills Estates, California, Earth Consultants International, June 15, 2000. Phase I Geologic and Geotechnical Engineering Study to Determine Potential Development Areas within the Chandler’s P.V. Sand and Gravel Company Property, Adjacent Trust Properties and the Rolling Hills Country Club, Rolling Hills Estates, California, Neblett & Associates, Inc., December 2001. Fault Investigation, Phases I and II, Chandler Quarry and Rolling Hills Country Club, Palos Verdes Estates, California, Neblett & Associates, Inc., April 29, 2005. Geotechnical Review, Geologic and Geotechnical Engineering Study, Potential Development Areas within the Chandler’s P.V. Sand and Gravel Company Property, Adjacent Trust Properties, and the Rolling Hills Country Club, City of Rolling Hills Estates, California, prepared by Arroyo Geotechnical, September 24, 2007. Review of Response Report, Geotechnical Review, Geologic and Geotechnical Engineering Study, Potential Development Areas within the Chandler’s P.V.