Working Wives and Mothers: What Happens to Family Life?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psychoanalytic Conceptions of Marriage and Marital Relationships 381 Been Discussing, Since These Figures Are Able to Reanimate Pictures of Their Mother Or Father

UNIVERSITY OF NIŠ The scientific journal FACTA UNIVERSITATIS Series: Philosophy and Sociology Vol.2, No 7, 2000 pp. 379 - 389 Editor of series: Gligorije Zaječaranović Address: Univerzitetski trg 2, 18000 Niš, YU Tel: +381 18 547-095, Fax: +381 18 547-950 PSYCHOANALYTIC CONCEPTIONS OF MARRIAGE AND MARITAL RELATIONSHIPS UDC 159.964.28+173.1+340.61 Zorica Marković University of Niš, Faculty of Philosophy, Niš, Yugoslavia Abstract. This work disclusses marital types and merital relationships as by several psychoanalysts: Sigmund Freud, Annie Reich, Helene Deutch, Knight Aldrich and Bela Mittelman. It analyzes kinds of relations hips, dynamics of interaction and inner mechanisms of interaction.Comparing marital types of the mentioned authors it can be seen that there is agreement among them and that they mainly represent further elaboration and "topic variation" of the basic marital types which are discussed by Sigmund Freud: anaclictic and narcissistic.Also, it can be concluded that all analysed marital types possess several common characteristics: 1. they are defined by relationships in childhood with parents or other important persons with whom a child was in touch; 2. dynamics of partner relationships is defined by unconscious motives; 3. same kinds of relationships and same type of partner selection a person repeats in all further attempts in spite of the fact that it does not give satisfactory results. Key words: psychoanalysis, marriage, partner, choice, relationships According to Si gmund Fr e ud , the founder of psychoanalysis, marital partner choice, as well as marital relationships, are defined much before marriage was concluded. Relationship with marital partner is determined by relationships with parents and important persons in one's childhood. -

Matrifocality and Women's Power on the Miskito Coast1

KU ScholarWorks | http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu Please share your stories about how Open Access to this article benefits you. Matrifocality and Women’s Power on the Miskito Coast by Laura Hobson Herlihy 2008 This is the published version of the article, made available with the permission of the publisher. The original published version can be found at the link below. Herlihy, Laura. (2008) “Matrifocality and Women’s Power on the Miskito Coast.” Ethnology 46(2): 133-150. Published version: http://ethnology.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/Ethnology/index Terms of Use: http://www2.ku.edu/~scholar/docs/license.shtml This work has been made available by the University of Kansas Libraries’ Office of Scholarly Communication and Copyright. MATRIFOCALITY AND WOMEN'S POWER ON THE MISKITO COAST1 Laura Hobson Herlihy University of Kansas Miskitu women in the village of Kuri (northeastern Honduras) live in matrilocal groups, while men work as deep-water lobster divers. Data reveal that with the long-term presence of the international lobster economy, Kuri has become increasingly matrilocal, matrifocal, and matrilineal. Female-centered social practices in Kuri represent broader patterns in Middle America caused by indigenous men's participation in the global economy. Indigenous women now play heightened roles in preserving cultural, linguistic, and social identities. (Gender, power, kinship, Miskitu women, Honduras) Along the Miskito Coast of northeastern Honduras, indigenous Miskitu men have participated in both subsistence-based and outside economies since the colonial era. For almost 200 years, international companies hired Miskitu men as wage- laborers in "boom and bust" extractive economies, including gold, bananas, and mahogany. -

Outline of the Book I. the Glorious Position of the Body of Christ (1:1-3:21) A

EPHESIANS.43 P a g e | 1 Outline of the Book I. The Glorious Position of the Body of Christ (1:1-3:21) A. Greetings (1:1-2) B. The Believer’s “Astounding Station” in Christ, to the praise of His glory (1:3-14) --- The Grace of the Father (1:3-6) --- The Grace of the Son (1:7-12) --- The Grace of the Spirit (1:13-14) C. Paul’s Motivated Prayer & Praise 1 (1:15-23) D. The Believer’s Collective Transport (2:1-10) --- Dead in Trespasses (2:1-3) --- Made Alive with Christ (2:4-10) E. Unified in Christ (2:11-22) --- Brought Near by the Blood (2:11-13) --- The Cross Creates One New Man (2:14-18) a. By Abolishing the Law (2:14-15) b. By Reconciling Us to the Father (2:16-18) --- Fellow Citizens in the Household of God (2:19-22) F. The Mystery of the Gospel (3:1-3:13) --- Prayer Interrupted (3:1) --- The Dispensation of God’s Grace (3:2-5) --- The Gentiles are Fellow Heirs (3:6-13) G. Paul’s Motivated Prayer & Praise 2 (3:14-21) II. The Glorious Practice of the Body of Christ (4:1-6:24) A. A Worthy Walk that Promotes Unity (4:1-6) B. Measures of Grace for Equipping the Body (4:7-16) C. Exhortation to Put on the New Self (4:17-24) D. Conduct that Benefits the Body (4:25-32) E. Serious Calling/Serious Consequences (5:1-21) F. Serious Calling Explained (5:22-6:20) --- The Example of Marriage (5:22-33) --- Parental Relationships (6:1-4) --- Occupational Relationships (6:5-9) --- Spiritual Opposition (6:10-20) G. -

Title 30. Husband and Wife Chapter 1 Marriage

Utah Code Title 30. Husband and Wife Chapter 1 Marriage 30-1-1 Incestuous marriages void. (1) The following marriages are incestuous and void from the beginning, whether the relationship is legitimate or illegitimate: (a) marriages between parents and children; (b) marriages between ancestors and descendants of every degree; (c) marriages between siblings of the half as well as the whole blood; (d) marriages between: (i) uncles and nieces or nephews; or (ii) aunts and nieces or nephews; (e) marriages between first cousins, except as provided in Subsection (2); or (f) marriages between any individuals related to each other within and not including the fifth degree of consanguinity computed according to the rules of the civil law, except as provided in Subsection (2). (2) First cousins may marry under the following circumstances: (a) both parties are 65 years of age or older; or (b) if both parties are 55 years of age or older, upon a finding by the district court, located in the district in which either party resides, that either party is unable to reproduce. Amended by Chapter 317, 2019 General Session 30-1-2 Marriages prohibited and void. (1) The following marriages are prohibited and declared void: (a) when there is a spouse living, from whom the individual marrying has not been divorced; (b) except as provided in Subsection (2), when an applicant is under 18 years old; and (c) between a divorced individual and any individual other than the one from whom the divorce was secured until the divorce decree becomes absolute, and, if an appeal is taken, until after the affirmance of the decree. -

Muang Matrifocality

MUANG MATRIFOCALITY by Richard Davis* The rural Muang (Yuan, Northern Thai), who inhabit the lowland areas of the northernmost provinces of Thailand and number over three million people, exhibit a social structure dominated by female ties. The two salient features of this social structure are a mandatory initial period of matrilocal residence, and matriclan organization. Both of these principles are reflected in the structure of the typical Muang dwelling. The most important component of a Muang house, and the part most hedged with taboos regarding its use, construction and location, is that part called the huan (hidn). The huan area of the house comprises the sleeping area, plus an open chamber called the tern (t;;;)n) which serves as a reception area for guests in the daytime and evenings and as the sleeping quarters for unmarried males at night. The sleeping area of most present-day houses is composed of two chambers delimited by the position of the houseposts. The household head and his wife and small children sleep in the chamber nearest the tern. The other cham ber is for unmarried daughters or a married daughter and son-in-law. In former times the sleeping area was larger, containing more chambers to house several married daughters and their husbands. The invisible bipartition of the enclosed part of the huan into two chambers, one for the household head and his wife and one for their married daughter and son-in-law, mirrors an important and distinctive feature of the Muang residence pattern. In rural Nan there is an obli gatory initial period of matrilocal residence, which usually lasts a year or more. -

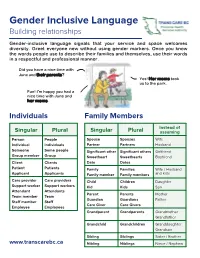

Gender Inclusive Language Building Relationships

Gender Inclusive Language Building relationships Gender-inclusive language signals that your service and space welcomes diversity. Greet everyone new without using gender markers. Once you know the words people use to describe their families and themselves, use their words in a respectful and professional manner. Did you have a nice time with June and their parents? Yes! Her moms took us to the park. Fun! I'm happy you had a nice time with June and her moms. Individuals Family Members Instead of Singular Plural Singular Plural assuming Person People Spouse Spouses Wife Individual Individuals Partner Partners Husband Someone Some people Significant other Significant others Girlfriend Group member Group Sweetheart Sweethearts Boyfriend Client Clients Date Dates Patient Patients Family Families Wife / Husband Applicant Applicants Family member Family members and kids Care provider Care providers Child Children Daughter Support worker Support workers Kid Kids Son Attendant Attendants Parent Parents Mother Team member Team Guardian Guardians Father Staff member Staff Care Giver Care Givers Employee Employees Grandparent Grandparents Grandmother Grandfather Grandchild Grandchildren Granddaughter Grandson Sibling Siblings Sister / Brother www.transcarebc.ca Nibling Niblings Niece / Nephew ii Pronouns (using they in the singular) If you are in a setting where your interactions with people are brief, you may not have time to get to know the person. Using the singular they in these situations can help to avoid pronoun mistakes. subject They They are waiting at the door. object Them The form is for them. possessive Their Their parents will pick them up at 3pm. adjective possessive Theirs They said the wheelchair is not theirs. -

Code of Ethics of the Family

Code of Ethics of the Family WANGO Copyright ©2010 by World Association of Non-Governmental Organizations (WANGO) Code of Ethics of the Family Preface The family is the core unit of society. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, enacted without dissent by the United Nations in 1948, notes this in stating that “the family is the natural and Stresses of urbanization and modernity have placed strains on the family and on marriage. This Code fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.” If society is designed to provide a frame of reference of those common features that help make successful were to be compared to an organism, families would be the cells. It is in the state’s interest to protect families. the family because, as the cornerstone of society, healthy families lead to a healthy society, analogous to healthy cells being necessary for a healthy organism. Developed under the auspices of the World Association of Non-Governmental Organizations (WANGO), in partnership with many organizations, the Code of Ethics of the Family was formulated Essentially, the family is the training ground of the heart and a textbook in which the husband by an international committee representing the broad spectrum of societies from all regions of the and wife are joint authors. It is in the family where we learn to care for others beyond ourselves, world. The original founding vision was provided by H.E. Dr. Abdelaziz Hegazy, former Prime to sacrifice ourselves for others, to love others. The most natural environment for a child to grow Minister of Egypt, and the Pennsylvania Family Coalition was the original founding partner providing mentally and spiritually from a state of selfishness and selfish behavior to unselfishness is the family practical assistance with the development of the Code. -

An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies

11 Close–Distant: An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies Abstract This chapter looks at the evidence for the close–distant dichotomy in the kinship systems of Australian Aboriginal societies. The close– distant dichotomy operates on two levels. It is the distinction familiar to Westerners from their own culture between close and distant relatives: those we have frequent contact with as opposed to those we know about but rarely, or never, see. In Aboriginal societies, there is a further distinction: those with whom we share our quotidian existence, and those who live at some physical distance, with whom we feel a social and cultural commonality, but also a decided sense of difference. This chapter gathers a substantial body of evidence to indicate that distance, both physical and genealogical, is a conception intrinsic to the Indigenous understanding of the function and purpose of kinship systems. Having done so, it explores the implications of the close–distant dichotomy for the understanding of pre-European Aboriginal societies in general—in other words: if the dichotomy is a key factor in how Indigenes structure their society, what does it say about the limits and integrity of the societies that employ that kinship system? 363 SKIN, KIN AND CLAN Introduction Kinship is synonymous with anthropology. Morgan’s (1871) Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family is one of the founding documents of the discipline. It also has an immediate connection to Australia: one of the first fieldworkers to assist Morgan in gathering his data was Lorimer Fison, who, later joined by A. -

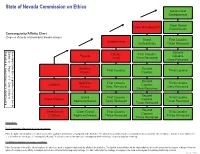

Third Degree of Consanguinity

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

Evolution of Marriage Systems

Evolution of marriage systems Laura Fortunato Institute of Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropology University of Oxford 64 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6PN, UK [email protected] +44 (0)1865 284971 Santa Fe Institute 1399 Hyde Park Road Santa Fe, NM 87501, USA Published as: Fortunato, L. (2015) Evolution of marriage systems. In Wright, J. D. (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed., vol. 14, pp. 611{619. Oxford: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.81059-4. 1 Contents 1 Definition of the subject 4 2 Key concepts 5 2.1 What is marriage? . .5 2.2 Classification of marriage systems . .6 2.3 Marriage, mating, and reproduction . .8 3 Evolutionary perspectives on marriage systems 10 3.1 Polygyny as the \default" mating and marriage system . 11 3.2 Polygynous marriage as resource defense polygyny . 13 3.3 The polygyny threshold model, female choice, and male coercion . 14 3.4 Monogamous marriage as socially imposed monogamy . 16 3.5 Monogamous marriage as \monogamous inheritance" . 18 3.6 Polyandrous marriage as a response to ecological challenges . 20 4 Concluding remarks 22 References 23 2 Abstract A marriage system is the set of rules and norms that regulate reproduction in a given human society. This article provides an overview of key concepts and general themes in the study of their evolution. The focus is on the number of spouses allowed (i.e. whether marriage is monogamous or polygamous), and the social and ecological factors associated with this aspect of the marriage system. Keywords marriage, kinship, family, inheritance, monogamy, polyandry, polygyny, polygamy, evolution of human social behaviour, human reproduction Cross-references Evolution of human mate choice, Evolution of kinship 3 1 Definition of the subject A marriage system is the set of rules and norms that regulate reproduction in a given human society. -

Beyond Fictions of Closure in Australian Aboriginal Kinship

MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL VOLUME 5 NO. 1 MAY 2013 BEYOND FICTIONS OF CLOSURE IN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL KINSHIP WOODROW W. DENHAM, PH. D RETIRED INDEPENDENT SCHOLAR [email protected] COPYRIGHT 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY AUTHOR SUBMITTED: DECEMBER 15, 2012 ACCEPTED: JANUARY 31, 2013 MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ISSN 1544-5879 DENHAM: BEYOND FICTIONS OF CLOSURE WWW.MATHEMATICALANTHROPOLOGY.ORG MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL VOLUME 5 NO. 1 PAGE 1 OF 90 MAY 2013 BEYOND FICTIONS OF CLOSURE IN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL KINSHIP WOODROW W. DENHAM, PH. D. Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Dedication .................................................................................................................................. 3 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 3 1. The problem ........................................................................................................................ 4 2. Demographic history ......................................................................................................... 10 Societal boundaries, nations and drainage basins ................................................................. 10 Exogamy rates ...................................................................................................................... -

What You Should Know About Common Law Marriage in Texas

Common Law Marriage in Texas WHAT YOU SHOULD KNOW ABOUT COMMON LAW MARRIAGE IN TEXAS SARAH A. DARNELL MICHELLE MAY O’NEIL O’Neil & Attorneys Family Law Lincoln Centre, Tower Two 5420 Lyndon B. Johnson Freeway Suite 500 Dallas, Texas 75240 (972) 852-8000 www.ONeilAttorneys.com As more and more people get away from the traditions of formal ceremonial marriages, it becomes more important to understand when and how you could find yourself in a common-law marriage relationship. Today more and more couples are cohabitating prior to marriage. Others choose to live together but never get married. There are many misconceptions about common-law marriage. There are many misunderstood facts about common law marriage in Texas. Knowing where the lines are drawn between unmarried and common law married can be important in knowing your rights. 10 MYTHS ABOUT COMMON LAW MARRIAGE Many people think the following situations constitute or raise a question about a couple’s marital status under common law: Myth 1: If we live together for 6 months or more, we are common law married. Myth 2: If we move in together at all, we are common law married. Myth 3: If we get engaged, we are agreeing to be common law married. Myth 4: If my girlfriend tells someone that we are married but I don’t agree, then we might be common law married. Myth 5: If my girlfriend uses my last name without my permission, then we might be common law married. Myth 6: If we agree to get married in the future, we are common law married now.