Muang Matrifocality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Developmental Effects on the Daughter of an Absent Father Throughout Her Lifespan

Merrimack College Merrimack ScholarWorks Honors Senior Capstone Projects Honors Program Spring 2020 The Developmental Effects on the Daughter of an Absent Father Throughout her Lifespan Carlee Castetter Merrimack College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/honors_capstones Part of the Child Psychology Commons, and the Developmental Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Castetter, Carlee, "The Developmental Effects on the Daughter of an Absent Father Throughout her Lifespan" (2020). Honors Senior Capstone Projects. 50. https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/honors_capstones/50 This Capstone - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at Merrimack ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Merrimack ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: EFFECTS OF ABSENT FATHER The Developmental Effects on the Daughter of an Absent Father Throughout her Lifespan Carlee Castetter Merrimack College Honors Senior Capstone Advised by Rebecca Babcock-Fenerci, Ph.D. Spring 2020 EFFECTS OF ABSENT FATHER 1 Abstract Fatherless households are becoming increasingly common throughout the United States. As a result, more and more children are growing up without the support of both parents, and this may be causing developmental consequences. While there has been significant research conducted on the effect of absent fathers on children in general, there has been far less research regarding girls specifically. As discovered in this paper, girls are often impacted differently than boys when it comes to growing up without a father. The current research paper aims to discover just exactly how girls are impacted by this lack of a parent throughout their lifetimes, from birth to adulthood. -

Psychoanalytic Conceptions of Marriage and Marital Relationships 381 Been Discussing, Since These Figures Are Able to Reanimate Pictures of Their Mother Or Father

UNIVERSITY OF NIŠ The scientific journal FACTA UNIVERSITATIS Series: Philosophy and Sociology Vol.2, No 7, 2000 pp. 379 - 389 Editor of series: Gligorije Zaječaranović Address: Univerzitetski trg 2, 18000 Niš, YU Tel: +381 18 547-095, Fax: +381 18 547-950 PSYCHOANALYTIC CONCEPTIONS OF MARRIAGE AND MARITAL RELATIONSHIPS UDC 159.964.28+173.1+340.61 Zorica Marković University of Niš, Faculty of Philosophy, Niš, Yugoslavia Abstract. This work disclusses marital types and merital relationships as by several psychoanalysts: Sigmund Freud, Annie Reich, Helene Deutch, Knight Aldrich and Bela Mittelman. It analyzes kinds of relations hips, dynamics of interaction and inner mechanisms of interaction.Comparing marital types of the mentioned authors it can be seen that there is agreement among them and that they mainly represent further elaboration and "topic variation" of the basic marital types which are discussed by Sigmund Freud: anaclictic and narcissistic.Also, it can be concluded that all analysed marital types possess several common characteristics: 1. they are defined by relationships in childhood with parents or other important persons with whom a child was in touch; 2. dynamics of partner relationships is defined by unconscious motives; 3. same kinds of relationships and same type of partner selection a person repeats in all further attempts in spite of the fact that it does not give satisfactory results. Key words: psychoanalysis, marriage, partner, choice, relationships According to Si gmund Fr e ud , the founder of psychoanalysis, marital partner choice, as well as marital relationships, are defined much before marriage was concluded. Relationship with marital partner is determined by relationships with parents and important persons in one's childhood. -

Matrifocality and Women's Power on the Miskito Coast1

KU ScholarWorks | http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu Please share your stories about how Open Access to this article benefits you. Matrifocality and Women’s Power on the Miskito Coast by Laura Hobson Herlihy 2008 This is the published version of the article, made available with the permission of the publisher. The original published version can be found at the link below. Herlihy, Laura. (2008) “Matrifocality and Women’s Power on the Miskito Coast.” Ethnology 46(2): 133-150. Published version: http://ethnology.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/Ethnology/index Terms of Use: http://www2.ku.edu/~scholar/docs/license.shtml This work has been made available by the University of Kansas Libraries’ Office of Scholarly Communication and Copyright. MATRIFOCALITY AND WOMEN'S POWER ON THE MISKITO COAST1 Laura Hobson Herlihy University of Kansas Miskitu women in the village of Kuri (northeastern Honduras) live in matrilocal groups, while men work as deep-water lobster divers. Data reveal that with the long-term presence of the international lobster economy, Kuri has become increasingly matrilocal, matrifocal, and matrilineal. Female-centered social practices in Kuri represent broader patterns in Middle America caused by indigenous men's participation in the global economy. Indigenous women now play heightened roles in preserving cultural, linguistic, and social identities. (Gender, power, kinship, Miskitu women, Honduras) Along the Miskito Coast of northeastern Honduras, indigenous Miskitu men have participated in both subsistence-based and outside economies since the colonial era. For almost 200 years, international companies hired Miskitu men as wage- laborers in "boom and bust" extractive economies, including gold, bananas, and mahogany. -

Outline of the Book I. the Glorious Position of the Body of Christ (1:1-3:21) A

EPHESIANS.43 P a g e | 1 Outline of the Book I. The Glorious Position of the Body of Christ (1:1-3:21) A. Greetings (1:1-2) B. The Believer’s “Astounding Station” in Christ, to the praise of His glory (1:3-14) --- The Grace of the Father (1:3-6) --- The Grace of the Son (1:7-12) --- The Grace of the Spirit (1:13-14) C. Paul’s Motivated Prayer & Praise 1 (1:15-23) D. The Believer’s Collective Transport (2:1-10) --- Dead in Trespasses (2:1-3) --- Made Alive with Christ (2:4-10) E. Unified in Christ (2:11-22) --- Brought Near by the Blood (2:11-13) --- The Cross Creates One New Man (2:14-18) a. By Abolishing the Law (2:14-15) b. By Reconciling Us to the Father (2:16-18) --- Fellow Citizens in the Household of God (2:19-22) F. The Mystery of the Gospel (3:1-3:13) --- Prayer Interrupted (3:1) --- The Dispensation of God’s Grace (3:2-5) --- The Gentiles are Fellow Heirs (3:6-13) G. Paul’s Motivated Prayer & Praise 2 (3:14-21) II. The Glorious Practice of the Body of Christ (4:1-6:24) A. A Worthy Walk that Promotes Unity (4:1-6) B. Measures of Grace for Equipping the Body (4:7-16) C. Exhortation to Put on the New Self (4:17-24) D. Conduct that Benefits the Body (4:25-32) E. Serious Calling/Serious Consequences (5:1-21) F. Serious Calling Explained (5:22-6:20) --- The Example of Marriage (5:22-33) --- Parental Relationships (6:1-4) --- Occupational Relationships (6:5-9) --- Spiritual Opposition (6:10-20) G. -

How Understanding the Aboriginal Kinship System Can Inform Better

How understanding the Aboriginal Kinship system can inform better policy and practice: social work research with the Larrakia and Warumungu Peoples of the Northern Territory Submitted by KAREN CHRISTINE KING BSW A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Social Work Faculty of Arts and Science Australian Catholic University December 2011 2 STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP AND SOURCES This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person‟s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the Australian Catholic University Human Research Ethics Committee. Karen Christine King BSW 9th March 2012 3 4 ABSTRACT This qualitative inquiry explored the kinship system of both the Larrakia and Warumungu peoples of the Northern Territory with the aim of informing social work theory and practice in Australia. It also aimed to return information to the knowledge holders for the purposes of strengthening Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing. This study is presented as a journey, with the oral story-telling traditions of the Larrakia and Warumungu embedded and laced throughout. The kinship system is unpacked in detail, and knowledge holders explain its benefits in their lives along with their support for sharing this knowledge with social workers. -

Title 30. Husband and Wife Chapter 1 Marriage

Utah Code Title 30. Husband and Wife Chapter 1 Marriage 30-1-1 Incestuous marriages void. (1) The following marriages are incestuous and void from the beginning, whether the relationship is legitimate or illegitimate: (a) marriages between parents and children; (b) marriages between ancestors and descendants of every degree; (c) marriages between siblings of the half as well as the whole blood; (d) marriages between: (i) uncles and nieces or nephews; or (ii) aunts and nieces or nephews; (e) marriages between first cousins, except as provided in Subsection (2); or (f) marriages between any individuals related to each other within and not including the fifth degree of consanguinity computed according to the rules of the civil law, except as provided in Subsection (2). (2) First cousins may marry under the following circumstances: (a) both parties are 65 years of age or older; or (b) if both parties are 55 years of age or older, upon a finding by the district court, located in the district in which either party resides, that either party is unable to reproduce. Amended by Chapter 317, 2019 General Session 30-1-2 Marriages prohibited and void. (1) The following marriages are prohibited and declared void: (a) when there is a spouse living, from whom the individual marrying has not been divorced; (b) except as provided in Subsection (2), when an applicant is under 18 years old; and (c) between a divorced individual and any individual other than the one from whom the divorce was secured until the divorce decree becomes absolute, and, if an appeal is taken, until after the affirmance of the decree. -

Gender Inclusive Language Building Relationships

Gender Inclusive Language Building relationships Gender-inclusive language signals that your service and space welcomes diversity. Greet everyone new without using gender markers. Once you know the words people use to describe their families and themselves, use their words in a respectful and professional manner. Did you have a nice time with June and their parents? Yes! Her moms took us to the park. Fun! I'm happy you had a nice time with June and her moms. Individuals Family Members Instead of Singular Plural Singular Plural assuming Person People Spouse Spouses Wife Individual Individuals Partner Partners Husband Someone Some people Significant other Significant others Girlfriend Group member Group Sweetheart Sweethearts Boyfriend Client Clients Date Dates Patient Patients Family Families Wife / Husband Applicant Applicants Family member Family members and kids Care provider Care providers Child Children Daughter Support worker Support workers Kid Kids Son Attendant Attendants Parent Parents Mother Team member Team Guardian Guardians Father Staff member Staff Care Giver Care Givers Employee Employees Grandparent Grandparents Grandmother Grandfather Grandchild Grandchildren Granddaughter Grandson Sibling Siblings Sister / Brother www.transcarebc.ca Nibling Niblings Niece / Nephew ii Pronouns (using they in the singular) If you are in a setting where your interactions with people are brief, you may not have time to get to know the person. Using the singular they in these situations can help to avoid pronoun mistakes. subject They They are waiting at the door. object Them The form is for them. possessive Their Their parents will pick them up at 3pm. adjective possessive Theirs They said the wheelchair is not theirs. -

Code of Ethics of the Family

Code of Ethics of the Family WANGO Copyright ©2010 by World Association of Non-Governmental Organizations (WANGO) Code of Ethics of the Family Preface The family is the core unit of society. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, enacted without dissent by the United Nations in 1948, notes this in stating that “the family is the natural and Stresses of urbanization and modernity have placed strains on the family and on marriage. This Code fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.” If society is designed to provide a frame of reference of those common features that help make successful were to be compared to an organism, families would be the cells. It is in the state’s interest to protect families. the family because, as the cornerstone of society, healthy families lead to a healthy society, analogous to healthy cells being necessary for a healthy organism. Developed under the auspices of the World Association of Non-Governmental Organizations (WANGO), in partnership with many organizations, the Code of Ethics of the Family was formulated Essentially, the family is the training ground of the heart and a textbook in which the husband by an international committee representing the broad spectrum of societies from all regions of the and wife are joint authors. It is in the family where we learn to care for others beyond ourselves, world. The original founding vision was provided by H.E. Dr. Abdelaziz Hegazy, former Prime to sacrifice ourselves for others, to love others. The most natural environment for a child to grow Minister of Egypt, and the Pennsylvania Family Coalition was the original founding partner providing mentally and spiritually from a state of selfishness and selfish behavior to unselfishness is the family practical assistance with the development of the Code. -

An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies

11 Close–Distant: An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies Abstract This chapter looks at the evidence for the close–distant dichotomy in the kinship systems of Australian Aboriginal societies. The close– distant dichotomy operates on two levels. It is the distinction familiar to Westerners from their own culture between close and distant relatives: those we have frequent contact with as opposed to those we know about but rarely, or never, see. In Aboriginal societies, there is a further distinction: those with whom we share our quotidian existence, and those who live at some physical distance, with whom we feel a social and cultural commonality, but also a decided sense of difference. This chapter gathers a substantial body of evidence to indicate that distance, both physical and genealogical, is a conception intrinsic to the Indigenous understanding of the function and purpose of kinship systems. Having done so, it explores the implications of the close–distant dichotomy for the understanding of pre-European Aboriginal societies in general—in other words: if the dichotomy is a key factor in how Indigenes structure their society, what does it say about the limits and integrity of the societies that employ that kinship system? 363 SKIN, KIN AND CLAN Introduction Kinship is synonymous with anthropology. Morgan’s (1871) Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family is one of the founding documents of the discipline. It also has an immediate connection to Australia: one of the first fieldworkers to assist Morgan in gathering his data was Lorimer Fison, who, later joined by A. -

Third Degree of Consanguinity

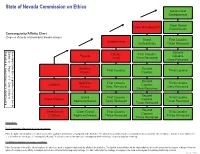

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

Bereavement Leave

STATE OF CALIFORNIA - DEPARTMENT OF GENERAL SERVICE PERSONNEL OPERATIONS MANUAL SUBJECT: BEREAVEMENT LEAVE REPRESENTED EMPLOYEES Bereavement leave allows for up to three (3) eight-hour days (24 hours) per occurrence or three (3) eight-hour days (24 hours) in a fiscal year based on the family member. The following chart describes the family member and bereavement leave allowed per bargaining unit. Bargaining Unit Eligible family member - three (3) eight-hour days Eligible family member - three (3) (24 hours) per occurrence eight-hour days (24 hours) in a fiscal year 1, 4, 11, 14, 15 • Parent • Aunt • Stepparent • Uncle • Spouse • Niece • Domestic Partner • Nephew • Child • immediate family members of • Grandchild Domestic Partners • Grandparent • Brother • Sister • Stepchild • Mother-in-Law • Father-in-Law • Daughter-in-Law • Son-in-Law • Sister-in-Law • Brother-in-Law • any person residing in the immediate household 2 • Parent • Grandchild • Stepparent • Grandparent • Spouse • Aunt • Domestic Partner • Uncle • Child • Niece • Sister • Nephew • Brother • Mother-in-Law • Stepchild • Father-in-Law • any person residing in the immediate household • Daughter-in-Law • Son-in-Law • Sister-in-Law • Brother-in-Law • immediate family member 7 • Parent • Grandchild • Stepparent • Grandparent • Spouse • Aunt • Domestic Partner • Uncle STATE OF CALIFORNIA - DEPARTMENT OF GENERAL SERVICE PERSONNEL OPERATIONS MANUAL Bargaining Unit Eligible family member - three (3) eight-hour days Eligible family member - three (3) (24 hours) per occurrence eight-hour -

Should the U.S. Approve Mitochondrial Replacement Therapy?

SHOULD THE U.S. APPROVE MITOCHONDRIAL REPLACEMENT THERAPY? An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By: ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Daniela Barbery Emily Caron Daniel Eckler IQP-43-DSA-6594 IQP-43-DSA-7057 IQP-43-DSA-5020 ____________________ ____________________ Benjamin Grondin Maureen Hester IQP-43-DSA-5487 IQP-43-DSA-2887 August 27, 2015 APPROVED: _________________________ Prof. David S. Adams, PhD WPI Project Advisor 1 ABSTRACT The overall goal of this project was to document and evaluate the new technology of mitochondrial replacement therapy (MRT), and to assess its technical, ethical, and legal problems to help determine whether MRT should be approved in the U.S. We performed a review of the current research literature and conducted interviews with academic researchers, in vitro fertility experts, and bioethicists. Based on the research performed for this project, our team’s overall recommendation is that the FDA approve MRT initially for a small number of patients, and follow their offspring’s progress closely for a few years before allowing the procedure to be done on a large scale. We recommend the FDA approve MRT only for treating mitochondrial disease, and recommend assigning parental rights only to the two nuclear donors. In medical research, animal models are useful but imperfect, and in vitro cell studies cannot provide information on long-term side-effects, so sometimes we just need to move forward with closely monitored human experiments. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page ……………………………….……………………………………..……. 01 Abstract …………………………………………………………………..…………. 02 Table of Contents ………………………………………………………………..… 03 Acknowledgements …………………………………………………………..…….