(Artiodactyla: Camelidae) Record from the Late Pleistocene of Calama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wild Or Bactrian Camel French: German: Wildkamel Spanish: Russian: Dikiy Verblud Chinese

1 of 4 Proposal I / 7 PROPOSAL FOR INCLUSION OF SPECIES ON THE APPENDICES OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS A. PROPOSAL: Inclusion of the Wild camel Camelus bactrianus in Appendix I of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals: B. PROPONENT: Mongolia C. SUPPORTING STATEMENT 1. Taxon 1.1. Classis: Mammalia 1.2. Ordo: Tylopoda 1.3. Familia: Camelidae 1.4. Genus: Camelus 1.5. Species: Camelus bactrianus Linnaeus, 1758 1.6. Common names: English: Wild or Bactrian camel French: German: Wildkamel Spanish: Russian: Dikiy verblud Chinese: 2. Biological data 2.1. Distribution Wild populations are restricted to 3 small, remnant populations in China and Mongolia:in the Taklamakan Desert, the deserts around Lop Nur, and the area in and around region A of Mongolia’s Great Gobi Strict Protected Area (Reading et al 2000). In addition, there is a small semi-captive herd of wild camels being maintained and bred outside of the Park. 2.2. Population Surveys over the past several decades have suggested a marked decline in wild bactrian camel numbers and reproductive success rates (Zhirnov and Ilyinsky 1986, Anonymous 1988, Tolgat and Schaller 1992, Tolgat 1995). Researchers suggest that fewer than 500 camels remain in Mongolia and that their population appears to be declining (Xiaoming and Schaller 1996). Globally, scientists have recently suggested that less than 900 individuals survive in small portions of Mongolia and China (Tolgat and Schaller 1992, Hare 1997, Tolgat 1995, Xiaoming and Schaller 1996). However, most of the population estimates from both China and Mongolia were made using methods which preclude rigorous population estimation. -

Bactrian Camel, Two-Humped Camel

Camelus ferus/bactrianus Common name: Bactrian camel, two-humped camel Local name: Havtagai (Mongolian), Wildkamel (German), Jya nishpa yapung (Ladakhi) Classification: Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Artiodactyla Family: Camelidae Genus: Camelus Species: ferus/bactrianus Profile: The scientific name of the wild Bactrian camel is Camelus ferus, while the domesticated form is called Camelus bactrianus. The distinctive feature of the animal is that it is two-humped whereas the Dromedary camel has a single hump. DNA tests have revealed that there are two or three distinct genetic differences and about 3% base difference between the wild and domestic populations of Bactrian camels. They also differ physically. The wild Bactrian camel is smaller and slender than the domestic breed. The wild camels have a sandy gray- brown coat while the domestic ones have a dark brown coat. The predominant difference between them however is the shape of the humps. While that of the wild camel are small and pyramid-like, those of the domestic ones are large and irregular. The face of a Bactrian camel is long and triangular with a split upper lip. The Bactrian camel is highly adapted to surviving the cold desert climate. Each foot has an undivided sole with two large toes that can spread wide apart for walking on sand. The ears and nose are lined with hair to protect against sand and the muscular nostrils can be closed during sandstorms. The eyes are protected from sand and debris by a double layer of long eyelashes while bushy eyebrows give protection from the sun. It grows a thick shaggy coat during winter, which is shed very rapidly in spring to give the animal a shorn look. -

1 BOARD of ANIMAL HEALTH Subpart 2 Chapter 12 Sheep And

BOARD OF ANIMAL HEALTH Subpart 2 Chapter 12 Sheep and Goats 109 All sheep and goats, except those for immediate slaughter shall be accompanied by an official certificate of veterinary inspection (OCVI) and shall comply with the following: 1. Intact sheep and goats require individual identification by an official USDA Scrapie eartag, brand, or tattoo recorded on the OCVI. 2. “I certify these animals are free of clinical signs of the diseases contagious footrot, keratoconjunctivitis, contagious ecthyma (Orf), scabies and lice and that the sexually intact animals represented on this form are not known to be scrapie- positive, suspect, high risk, or exposed, and did not originate from a known infected, source, exposed, or noncompliant flock.” 3. When originating from an area known to have scabies, must be dipped within ten (10) days immediately preceding the date of entry in an USDA approved dip, and maintained on absolutely clean premises until delivered to the final destination. Dairy goats and dairy sheep maintained separate from other sheep and goats are exempt from dipping when certified free of scabies on OCVI. 4. Dairy goats and dairy sheep over 6 months of age must be negative to an official tuberculin test and an official brucellosis test made within 30 days immediately preceding date of entry. 5. All sheep and goats for immediate slaughter shall be consigned to a recognized slaughtering establishment on either an OCVI or permit or waybill or inspection certification from federally inspected stockyards. In either instance, a copy shall accompany sheep and goats and a copy shall be forwarded to the State Veterinarian of Mississippi. -

Pleistocene Mammals from Extinction Cave, Belize

Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Pleistocene Mammals From Extinction Cave, Belize Journal: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Manuscript ID cjes-2018-0178.R3 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the 04-May-2019 Author: Complete List of Authors: Churcher, C.S.; University of Toronto, Zoology Central America, Pleistocene, Fauna, Vertebrate Palaeontology, Keyword: Limestone cave Is the invited manuscript for consideration in a Special Not applicableDraft (regular submission) Issue? : https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/cjes-pubs Page 1 of 43 Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1 1 PLEISTOCENE MAMMALS FROM EXTINCTION CAVE, BELIZE 2 by C.S. CHURCHER1 Draft 1Department of Zoology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario Canada M5S 2C6 and 322-240 Dallas Rd., Victoria, British Columbia, Canada V8V 4X9 (corresponding address): e-mail [email protected] https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/cjes-pubs Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Page 2 of 43 2 4 5 ABSTRACT. A small mammalian fauna is recorded from Extinction Cave (also called Sibun 6 Cave), east of Belmopan, on the Sibun River, Belize, Central America. The animals recognized 7 are armadillo (†Dasypus bellus), American lion (†Panthera atrox), jaguar (P. onca), puma or 8 mountain lion (Puma concolor), Florida spectacled bear (†Tremarctos floridanus), javelina or 9 collared peccary (Pecari tajacu), llama (Camelidae indet., ?†Palaeolama mirifica), red brocket 10 deer (Mazama americana), bison (Bison sp.) and Mexican half-ass (†Equus conversidens), and 11 sabre-tooth cat († Smilodon fatalis) may also be represented (‘†’ indicates an extinct taxon). 12 Bear and bison are absent from the region today. The bison record is one of the more southernly 13 known. The bear record is almost the mostDraft westerly known and a first for Central America. -

Prospects for Rewilding with Camelids

Journal of Arid Environments 130 (2016) 54e61 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Arid Environments journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jaridenv Prospects for rewilding with camelids Meredith Root-Bernstein a, b, *, Jens-Christian Svenning a a Section for Ecoinformatics & Biodiversity, Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark b Institute for Ecology and Biodiversity, Santiago, Chile article info abstract Article history: The wild camelids wild Bactrian camel (Camelus ferus), guanaco (Lama guanicoe), and vicuna~ (Vicugna Received 12 August 2015 vicugna) as well as their domestic relatives llama (Lama glama), alpaca (Vicugna pacos), dromedary Received in revised form (Camelus dromedarius) and domestic Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) may be good candidates for 20 November 2015 rewilding, either as proxy species for extinct camelids or other herbivores, or as reintroductions to their Accepted 23 March 2016 former ranges. Camels were among the first species recommended for Pleistocene rewilding. Camelids have been abundant and widely distributed since the mid-Cenozoic and were among the first species recommended for Pleistocene rewilding. They show a range of adaptations to dry and marginal habitats, keywords: Camelids and have been found in deserts, grasslands and savannas throughout paleohistory. Camelids have also Camel developed close relationships with pastoralist and farming cultures wherever they occur. We review the Guanaco evolutionary and paleoecological history of extinct and extant camelids, and then discuss their potential Llama ecological roles within rewilding projects for deserts, grasslands and savannas. The functional ecosystem Rewilding ecology of camelids has not been well researched, and we highlight functions that camelids are likely to Vicuna~ have, but which require further study. -

Paleobiology of a Large Mammal Community from the Late Pleistocene of Sonora, Mexico

Quaternary Research (2021), 102, 247–259 doi:10.1017/qua.2020.125 Research Article Paleobiology of a large mammal community from the late Pleistocene of Sonora, Mexico Rachel A. Shorta* , Laura G. Emmertb, Nicholas A. Famosoc,d, Jeff M. Martina,†, Jim I. Meade,f, Sandy L. Swifte and Arturo Baezg aDepartment of Ecology and Conservation Biology, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 77843 USA; bDon Sundquist Center of Excellence in Paleontology, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, Tennessee 37614 USA; cJohn Day Fossil Beds National Monument, U.S. National Park Service, Kimberly, Oregon 97848 USA; dDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403 USA; eThe Mammoth Site of Hot Springs, S.D.,1800 Hwy 18 Bypass, Hot Springs, South Dakota, 57747 USA; fDesert Laboratory on Tumamoc Hill, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85745 USA and gCollege of Agriculture and Life Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721 USA Abstract A paleontological deposit near San Clemente de Térapa represents one of the very few Rancholabrean North American Land Mammal Age sites within Sonora, Mexico. During that time, grasslands were common, and the climate included cooler and drier summers and wetter winters than currently experienced in northern Mexico. Here, we demonstrate restructuring in the mammalian community associated with environmental change over the past 40,000 years at Térapa. The fossil community has a similar number of carnivores and herbivores whereas the modern community consists mostly of carnivores. There was also a 97% decrease in mean body size (from 289 kg to 9 kg) because of the loss of megafauna. -

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals Secretariat provided by the United Nations Environment Programme 16TH MEETING OF THE CMS SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL Bonn, Germany, 28-30 June, 2010 UNEP/CMS/ScC16/Inf.10 Agenda Item No. 13.3a COMPILATION OF (RE-) EMERGING TRANSMISSIBLE DISEASES IN MIGRATORY SPECIES (Prepared for the CMS Secretariat by Philipp Zimmermann, DVM, PhD) 1. COP Resolution 9.8 calls on the CMS Secretariat and the FAO Animal Health Service to co-convene a new task force, the Scientific Task Force on Wildlife Disease, with the aim of identifying diseases that have an impact on both domestic and wildlife species, and that are of greatest concern with regard to food security, economics and sustainable livelihoods. 2. The new task force is also meant to develop responses to emerging and re-emerging diseases in migratory species, taking into account the fact that integration of both wildlife and domestic animal issues is required to understand disease epidemiology properly as well as to address disease transmission, control and prevention. 3. As a basis for the work of the new task force, two tables have been prepared, one on transmissible diseases of viral origin (Annex I) and another on transmissible diseases of bacterial origin (Annex II). These tables summarize the most relevant diseases that can affect wild animals, and include information on species affected, outbreaks, transmission, and treatment and control mechanisms. 4. The sources and criteria used include: - The Transmissible Diseases Handbook, 3rd Edition, European Association of Zoo and Wildlife Veterinarians - The Field Manual on Wildlife Diseases, US Geological Survey - Review of selected literature 5. -

Giant Camels from the Cenozoic of North America SERIES PUBLICATIONS of the SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

Giant Camels from the Cenozoic of North America SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the H^arine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that refXJrt the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the worid. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. Press requirements for manuscript and art preparation are outlined on the inside back cover. -

Deer from Late Miocene to Pleistocene of Western Palearctic: Matching Fossil Record and Molecular Phylogeny Data

Zitteliana B 32 (2014) 115 Deer from Late Miocene to Pleistocene of Western Palearctic: matching fossil record and molecular phylogeny data Roman Croitor Zitteliana B 32, 115 – 153 München, 31.12.2014 Institute of Cultural Heritage, Academy of Sciences of Moldova, Bd. Stefan Cel Mare 1, Md-2028, Chisinau, Moldova; Manuscript received 02.06.2014; revision E-mail: [email protected] accepted 11.11.2014 ISSN 1612 - 4138 Abstract This article proposes a brief overview of opinions on cervid systematics and phylogeny, as well as some unresolved taxonomical issues, morphology and systematics of the most important or little known mainland cervid genera and species from Late Miocene and Plio-Pleistocene of Western Eurasia and from Late Pleistocene and Holocene of North Africa. The Late Miocene genera Cervavitus and Pliocervus from Western Eurasia are included in the subfamily Capreolinae. A cervid close to Cervavitus could be a direct forerunner of the modern genus Alces. The matching of results of molecular phylogeny and data from cervid paleontological record revealed the paleozoogeographical context of origin of modern cervid subfamilies. Subfamilies Capreolinae and Cervinae are regarded as two Late Miocene adaptive radiations within the Palearctic zoogeographic province and Eastern part of Oriental province respectively. The modern clade of Eurasian Capreolinae is significantly depleted due to climate shifts that repeatedly changed climate-geographic conditions of Northern Eurasia. The clade of Cervinae that evolved in stable subtropical conditions gave several later radiations (including the latest one with Cervus, Rusa, Panolia, and Hyelaphus) and remains generally intact until present days. During Plio-Pleistocene, cervines repeatedly dispersed in Palearctic part of Eurasia, however many of those lineages have become extinct. -

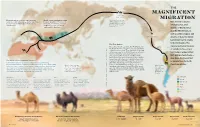

Magnificent Migration

THE MAGNIFICENT Land bridge 8 MY–14,500 Y MIGRATION Domestication of camels began between World camel population today About 6 million years ago, 3,000 and 4,000 years ago—slightly later than is about 30 million: 27 million of camelids began to move Best known today for horses—in both the Arabian Peninsula and these are dromedaries; 3 million westward across the land Camelini western Asia. are Bactrians; and only about that connected Asia and inhabiting hot, arid North America. 1,000 are Wild Bactrians. regions of North Africa and the Middle East, as well as colder steppes and Camelid ancestors deserts of Asia, the family Camelidae had its origins in North America. The The First Camels signature physical features The earliest-known camelids, the Protylopus and Lamini E the Poebrotherium, ranged in sizes comparable to of camels today—one or modern hares to goats. They appeared roughly 40 DMOR I SK million years ago in the North American savannah. two humps, wide padded U L Over the 20 million years that followed, more U L ; feet, well-protected eyes— O than a dozen other ancestral members of the T T O family Camelidae grew, developing larger bodies, . E may have developed K longer legs and long necks to better browse high C I The World's Most Adaptable Traveler? R ; vegetation. Some, like Megacamelus, grew even I as adaptations to North Camels have adapted to some of the Earth’s most demanding taller than the woolly mammoths in their time. LEWSK (Later, in the Middle East, the Syrian camel may American winters. -

2021 Bering Land Bridge National Preserve Superintendent's

BERING LAND BRIDGE NATIONAL PRESERVE 2021 COMPENDIUM SIGNED ORIGINAL ON FILE National Park Service (NPS) regulations applicable to the protection and equitable public use of units of the National Park System grant specified authorities to a park superintendent to allow or restrict certain activities. NPS regulations are found in Titles 36 and 43 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) and created under authority and responsibility granted the Secretary of Interior in Titles 16 and 54 of the United States Code. The following compendium comprises a listing of NPS regulations that provide the Superintendent with discretionary authority to make designations or impose public use restrictions or conditions in park areas. The applicability and scope of the compendium is articulated in 36 CFR Sections 1.2 and 13.2, and 43 CFR Section 36.1. A complete and accurate picture of regulations governing use and protection of the unit can only be gained by viewing this compendium in context with the full body of applicable regulations found in Titles 36 and 43 CFR. Please contact Bering Land Bridge National Preserve, P.O. Box 220, Nome, Alaska 99762 or call (800) 471-2352 for questions relating to information provided in this compendium. TITLE 36 CODE OF FEDERAL REGULATIONS PART 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS 1.6(f) Compilation of activities requiring a permit • Collecting research specimens, 2.5 • Operating a power saw in developed areas, 2.12(a)(2) • Operating a portable motor or engine in undeveloped areas, 2.12(a)(3) • Operating a public address system, 2.12(a)(4) -

Description of a Fossil Camelid from the Pleistocene of Argentina, and a Cladistic Analysis of the Camelinae

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2020 Description of a fossil camelid from the Pleistocene of Argentina, and a cladistic analysis of the Camelinae Lynch, Sinéad ; Sánchez-Villagra, Marcelo R ; Balcarcel, Ana Abstract: We describe a well-preserved South American Lamini partial skeleton (PIMUZ A/V 4165) from the Ensenadan ( 1.95–1.77 to 0.4 Mya) of Argentina. The specimen is comprised of a nearly complete skull and mandible with full tooth rows, multiple elements of anterior and posterior limbs, and a scapula. We tested this specimen’s phylogenetic position and hypothesized it to be more closely related to Lama guanicoe and Vicugna vicugna than to Hemiauchenia paradoxa. We formulate a hypothesis for the placement of PIMUZ A/V 4165 within Camelinae in a cladistic analysis based on craniomandibular and dental characters and propose that future systematic studies consider this specimen as representing a new species. For the first time in a morphological phylogeny, we code terminal taxa at the species levelfor the following genera: Camelops, Aepycamelus, Pleiolama, Procamelus, and Alforjas. Our results indicate a divergence between Lamini and Camelini predating the Barstovian (16 Mya). Camelops appears as monophyletic within the Camelini. Alforjas taylori falls out as a basal member of Camelinae—neither as a Lamini nor Camelini. Pleiolama is polyphyletic, with Pleiolama vera as a basal Lamini and Pleiolama mckennai in a more nested position within the Lamini. Aepycamelus and Procamelus are respectively polyphyletic and paraphyletic. Together, they are part of a group of North American Lamini from the Miocene epoch.