One Thousand and One Nights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

272 the 1960S and 1970S. the Reviewer Believes the Author Could Have Made Greater Use of It. a Name Index Would Be Desirable. St

272 REVIEWS the 1960s and 1970s. The reviewer believes the author could have made greater use of it. A name index would be desirable. Stephan Guth's book is the result of conscientious research efforts and a great enthusiasm for the chosen subject. It contributes notably to the understanding of current literary developments in Egypt. Anyone dealing with modern Egyp- tian literature will find in it much valuable information and stimulating ideas. Charles University, Prague JAROSLAVOLIVERIUS DAVID PINAULT, Story-telling Techniques in the Arabian Nights, Leiden, E.J. Brill 1992. IX, 262 pp. (Studies in Arabic Literature. Supplements to the Journal of Arabic Literature, ed. M.M. Badawi and J. N. Mattock, Vol. XV). This book has its origin in a doctoral dissertation, finished in 1986 at the University of Pennsylvania. The author wants to address the general reader as well as the student of Arabic literature, so he gives all the Arabic passages in translation and summarizes the plots of the stories before he analyzes them. He defines his main purpose as to find out "What narrative techniques are favored by the Alf Lailah story tellers for engaging an audience? And: In what ways does the redactor make use of pre-existent material?" (p. IX). To be able to answer this question he compares the different printed versions of the stories he analyzes: Bflaq (II), Macnaghten (not MacNaghten), to a very limited extent Habicht and, of course, the Leiden edition of Galland's manuscript by Muhsin Mahdi. He also compares some of the stories he analyzes with similar or nearly identical stories which he has found in hitherto unpublished manuscripts of anthologies of popular narrative independent of "The Nights", to be found in some North African and French libraries. -

The Arabian Nights Free Download

THE ARABIAN NIGHTS FREE DOWNLOAD Richard Burton,Kenneth C. Mondschein | 750 pages | 24 Nov 2011 | Advantage Publishers Group | 9781607103097 | English | San Diego, United States The Arabian Nights Archived from the original on 6 March Accessed May 9, The fisherman tricks the genie into returning to the jar, and then tells him the story of "The Vizier and the Sage Duban ," detailed below. Try reading the story you are interested in first, then decide if it is appropriate material for your young listener. Comment Name Email Website Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time The Arabian Nights comment. The framework works nicely; the harried sultan, initially all sweat and paranoia, set on the path to redemption by his new wife Scheherezade Mili Avital, who is just exquisitewho must The Arabian Nights his interest by telling him stories or be executed. The story ends with the king in such disgust at the tale Scheherazade has just woven, that he has her executed the very next day. Yunan has Duban executed on that suspicion, and Duban gifts him a magic book before The Arabian Nights dies. A further four volumes followed in — The Arabian Nights Parents Guide. Bearman; Th. Today it is the official language of IranTajikistan and one of the The Arabian Nights official languages of Afghanistan. Brother to Shahzaman. Please exercise care when reading them to young children. Crazy Credits. Tauris Parke Paperbacks Kindle edition. The source for most later translations, however, was The Arabian Nights so-called Vulgate text, an Egyptian recension published at BulaqCairoinand several times reprinted. -

VCU Open 2013 Round #2

VCU Open 2013 Round 2 Tossups 1. Just before leaving this location, a story about the origin of certain rivers is told, involving a statue that is made of a gold head, silver chest, brass midection, iron legs, and one clay foot, which stands on Mount Ida. The author of the Trésor is seen at this location, as is an advisor to Frederick II who was blinded for supposed treachery. Another person in this location is depicted as lying on his back in echo of the Thebiad. This location is where Pier della Vigna and Capaneus are encountered. Many former residents of the city of Cahors are found in this location, as is Bruno Lattini. A river of blood in this location contains men who are prevented from climbing out by arrows fired by centaurs. Access to this location is impeded by a pile of boulders, on top of which sits the Minotaur, who begins to bite himself and buck about, upon hearing the name of Theseus. Certain people here are changed into trees gnawed at by the Harpies in this location. For 10 points, name this circle of Hell in the Inferno where those guilty of blasphemy, usury, sodomy, suicide, and murder are found, located just above a circle with many "bolgia." ANSWER: the seventh circle of Hell [or 7, etc.; prompt on Hell or Inferno] 019-13-64-02101 2. A scandal involving this party was revealed by Sheila Fraser and investigated by the Gomery Commission. A member of this party who was killed in a plane crash was Norman Rogers. -

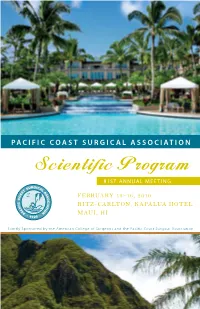

Scientific Program 81S T Annual M Ee T in G

P A C I F I C C O A S T S U R G I C A L A SSOCIATION Scientific Program 81S T ANNUAL M EE T IN G FEBRUARY 13–16, 2010 RITZ-CARLTON, KAPALUA HOTEL MAUI, HI Jointly Sponsored by the American College of Surgeons and the Pacific Coast Surgical Association TABLE OF CONTENTS P A C I F I C C O A S T S U R G I C A L A SSOCIATION 8 1 S T A N N U A L M E E T I N G Scientific Program FEBRUARY 13–16, 2010 Ritz-CaRlton, Kapalua Hotel • Maui, Hi Ta BLE OF CONTENTS Arrangements/Program Committee .....................................................................2 Council officers, Members, and Representatives ................................................3 General Information ..................................................................................................4 Program Information ................................................................................................5 Scientific Program .....................................................................................................6 industry Support Displays .......................................................................................7 evening activities ......................................................................................................8 optional activities .....................................................................................................9 program agenda ......................................................................................................11 Scientific Session agenda .......................................................................................13 -

A Structural Approach to the Arabian Nights

AWEJ. Special Issue on Literature No.2 October, 2014 Pp. 125- 136 A Structural Approach to The Arabian Nights Sura M. Khrais Department of English Language and Literature Princess Alia University College Al-Balqa Applied University Amman, Jordan Abstract This paper introduces a structural study of The Arabian Nights, Book III. The structural approach used by Vladimir Propp on the Russian folktales along with Tzvetan Todorov's ideas on the literature of the fantastic will be applied here. The researcher argues that structural reading of the chosen ten stories is fruitful because structuralism focuses on multiple texts, seeking how these texts unify themselves into a coherent system. This approach enables readers to study the text as a manifestation of an abstract structure. The paper will concentrate on three different aspects: character types, narrative technique and setting (elements of place). First, the researcher classifies characters according to their contribution to the action. Propp's theory of the function of the dramatist personae will be adopted in this respect. The researcher will discuss thirteen different functions. Then, the same characters will be classified according to their conformity to reality into historical, imaginative, and fairy characters. The role of the fairy characters in The Arabian Nights will be highlighted and in this respect Vladimir's theory of the fantastic will be used to study the significance of the supernatural elements in the target texts. Next, the narrative techniques in The Arabian Nights will be discussed in details with a special emphasis on the frame story technique. Finally, the paper shall discuss the features of place in the tales and show their distinctive yet common elements. -

SCHEHERAZADE a Musical Fantasy

Alan Gilbert Music Director SCHEHERAZADE A Musical Fantasy School Day Concerts 2013 Resource Materials for Teachers Education at the New York Philharmonic The New York Philharmonic’s education programs open doors to symphonic music for people of all ages and backgrounds, serving over 40,000 young people, families, teachers, and music professionals each year. The School Day Concerts are central to our partnerships with schools in New York City and beyond. The pioneering School Partnership Program joins Philharmonic Teaching Artists with classroom teachers and music teachers in full-year residencies. Currently more than 4,000 students at 16 New York City schools in all five boroughs are participating in the three-year curriculum, gaining skills in playing, singing, listening, and composing. For over 80 years the Young People’s Concerts have introduced children and families to the wonders of orchestral sound; on four Saturday afternoons, the promenades of Avery Fisher Hall become a carnival of hands-on activities, leading into a lively concert. Very Young People’s Concerts engage pre-schoolers in hands-on music-making with members of the New York Philharmonic. The fun and learning continue at home through the Philharmonic’s award-winning website Kidzone! , a virtual world full of games and information designed for young browsers. To learn more about these and the Philharmonic’s many other education programs, visit nyphil.org/education , or go to Kidzone! at nyphilkids.org to start exploring the world of orchestral music right now. The School Day Concerts are made possible with support from the Carson Family Charitable Trust and the Mary and James G. -

Hi-Resolution Map Sheet

Controlled Mosaic of Enceladus Hamah Sulci Se 400K 43.5/315 CMN, 2018 GENERAL NOTES 66° 360° West This map sheet is the 5th of a 15-quadrangle series covering the entire surface of Enceladus at a 66° nominal scale of 1: 400 000. This map series is the third version of the Enceladus atlas and 1 270° West supersedes the release from 2010 . The source of map data was the Cassini imaging experiment (Porco et al., 2004)2. Cassini-Huygens is a joint NASA/ESA/ASI mission to explore the Saturnian 350° system. The Cassini spacecraft is the first spacecraft studying the Saturnian system of rings and 280° moons from orbit; it entered Saturnian orbit on July 1st, 2004. The Cassini orbiter has 12 instruments. One of them is the Cassini Imaging Science Subsystem 340° (ISS), consisting of two framing cameras. The narrow angle camera is a reflecting telescope with 290° a focal length of 2000 mm and a field of view of 0.35 degrees. The wide angle camera is a refractor Samad with a focal length of 200 mm and a field of view of 3.5 degrees. Each camera is equipped with a 330° 300° large number of spectral filters which, taken together, span the electromagnetic spectrum from 0.2 60° 320° 310° to 1.1 micrometers. At the heart of each camera is a charged coupled device (CCD) detector 60° consisting of a 1024 square array of pixels, each 12 microns on a side. MAP SHEET DESIGNATION Peri-Banu Se Enceladus (Saturnian satellite) 400K Scale 1 : 400 000 43.5/315 Center point in degrees consisting of latitude/west longitude CMN Controlled Mosaic with Nomenclature Duban 2018 Year of publication IMAGE PROCESSING3 Julnar Ahmad - Radiometric correction of the images - Creation of a dense tie point network 50° - Multiple least-square bundle adjustments 50° - Ortho-image mosaicking Yunan CONTROL For the Cassini mission, spacecraft position and camera pointing data are available in the form of SPICE kernels. -

Sir Richard Francis Burton Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8028x7j No online items Sir Richard Francis Burton Papers: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Gayle M. Richardson. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2009 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Sir Richard Francis Burton mssRFB 1-1386 1 Papers: Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Sir Richard Francis Burton Papers Dates (inclusive): 1846-2003 Bulk dates: 1846-1939 Collection Number: mssRFB 1-1386 Creator: Burton, Richard Francis, Sir, 1821-1890. Extent: 1,461 pieces. 58 boxes. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains personal, official, business, and social correspondence and manuscripts of British explorer and writer Sir Richard Francis Burton (1821-1890) and his wife, Lady Isabel Burton (1831-1896), chiefly covering the period of Burton's consulship in Trieste and Lady Burton's life after her husband's death. Language: English. Significant languages represented other than English: French, Spanish, Italian, German, Arabic, Portuguese. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. -

Alaeddin and the Enchanted Lamp

Alaeddin and the Enchanted Lamp John Payne Alaeddin and the Enchanted Lamp Table of Contents Alaeddin and the Enchanted Lamp.........................................................................................................................1 John Payne.....................................................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................................................2 I......................................................................................................................................................................2 II....................................................................................................................................................................3 III....................................................................................................................................................................4 IV...................................................................................................................................................................6 V.....................................................................................................................................................................7 ZEIN UL ASNAM AND THE KING OF THE JINN...............................................................................................8 ALAEDDIN AND -

Contents More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47485-6 — The Arabian Nights in Contemporary World Cultures Muhsin J. al-Musawi Table of Contents More Information Contents List of Figures page x Acknowledgments xi Introduction: The Stunning Growth of a Constellation 1 1 The Arabian Nights: A European Legacy? 23 A Phenomenal Arabian Nightism!23 The Travels of a “Coarse Book” 29 Knowledge Consortiums 32 Like a Jar of Sicilian Honey? Or “Spaces of Dissension”?35 Reclaiming a Poetics of Storytelling 38 Shifts in Periodical Criticism of the Nights: Old and New 42 A Decolonizing Critique 43 Constants and Variables 48 2 The Scheherazade Factor 52 The Empowering Dynamic 52 The Scheherazade Factor and Serial Narrative 57 Narrative Framing 59 The Frame Setting and Story 61 Relativity of Individual Blight 63 An Underlying Complexity 65 The Dynamics of the Frame Tale 66 The Missing Preliminary Volatile Sites 67 Pre-Scheherazade Women Actors 71 The Preludinal Site of Nuptial Failure 74 What Does the Muslim Chronicler Tell? 78 The Garden Site: The Spectacle 85 3 Engagements in Narrative 93 From Bethlehem to Havana: Imaginative Flights of the Nights 93 Butor’s Second Mendicant and the Narrative Globe-Trotter 95 Confabulación Nocturna: Reinventing Scheherazade 97 Borges’s Poetics of Prose 103 The Ever-Unfinished Work: Scheherazade’s Proust 107 Barth’s Linking: Sex and Narrative 109 Why Invest More in Dunyazade? 112 vii © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47485-6 — The Arabian Nights in Contemporary -

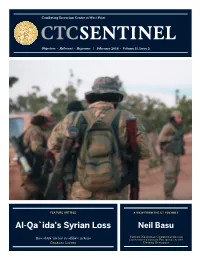

CTC Sentinel Welcomes Submissions

Combating Terrorism Center at West Point Objective • Relevant • Rigorous | February 2018 • Volume 11, Issue 2 FEATURE ARTICLE A VIEW FROM THE CT FOXHOLE Al-Qa`ida's Syrian Loss Neil Basu Senior National Coordinator for How al-Qa`ida lost its afliate in Syria Counterterrorism Policing in the Charles Lister United Kingdom FEATURE ARTICLE Editor in Chief 1 How al-Qa`ida Lost Control of its Syrian Afliate: The Inside Story Charles Lister Paul Cruickshank Managing Editor INTERVIEW Kristina Hummel 10 A View from the CT Foxhole: Neil Basu, Senior National Coordinator for Counterterrorism Policing in the United Kingdom EDITORIAL BOARD Raffaello Pantucci Colonel Suzanne Nielsen, Ph.D. Department Head ANALYSIS Dept. of Social Sciences (West Point) 15 Can the UAE and its Security Forces Avoid a Wrong Turn in Yemen? Lieutenant Colonel Bryan Price, Ph.D. Michael Horton Director, CTC 20 Letters from Home: Hezbollah Mothers and the Culture of Martyrdom Kendall Bianchi Brian Dodwell Deputy Director, CTC 25 Beyond the Conflict Zone: U.S. HSI Cooperation with Europol Miles Hidalgo CONTACT Combating Terrorism Center The Combating Terrorism Center at West Point is proud to mark its 15th year anniversary this month. In this issue’s feature article, Charles Lister tells the U.S. Military Academy inside story of how al-Qa`ida lost control of its Syrian afliate, drawing on the 607 Cullum Road, Lincoln Hall public statements of several key protagonists as well as interviews with Islamist sources in Syria. In the West Point, NY 10996 summer of 2016, al-Qa`ida’s Syrian afliate, Jabhat al-Nusra, announced it was uncoupling from al-Qa`ida and rebranding itself. -

The August Meeting Will Convene in Shanahan B460 - -

The August meeting will convene in Shanahan B460 - - - Volume 34 Number 8 nightwatch August 2014 President's Message Lots going on in space these days. The biggest news is the rendezvous of the European Space One last thing—if you haven’t gotten your annual dues Agency's Rosetta probe with Comet 67P/Churyumov- turned in; please do so immediately, before we have to start Gerasimenko on August 6. Rosetta is settling in a series of lower sending out personal reminders! orbits around the comet nucleus. If all goes well, Rosetta's Matt Wedel lander, called Philae, will set down on the comet sometime this November. A little farther out—okay, a LOT farther out—NASA's New Club Events Calendar Horizon probe shot a time-lapse video of Pluto and Charon orbiting each other. This is just a first taste of the data that New August 15, General meeting – Jim Gallivan Horizon will send back between now and it's flyby of the Pluto The Unification of Astronomy, Astrology, GPS, Supernovae system next July. and UFOs August 23, Star Party On August 5, a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket successfully boosted Asiasat-8 to a geosynchronous transfer orbit. Video taken by September 4, Board meeting, 6:15 cameras on board the first stage of the rocket showed it making a September 12, General meeting controlled descent toward the Atlantic Ocean, but unfortunately September 27, Mt Wilson Observing the first stage broke up in heavy seas before it could be retrieved. There's plenty to wow Earthbound observers as well, from October 2, Board meeting 6:15 last weekend's "supermoon" to the peak of the Perseid meteor October 10, General meeting October 25, Star Party shower on the evening of August 12 and 13.