Tent-Roosting May Have Driven the Evolution of Yellow Skin Coloration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chocó-Darién Conservation Corridor

July 4, 2011 The Chocó-Darién Conservation Corridor A Project Design Note for Validation to Climate, Community, and Biodiversity (CCB) Standards (2nd Edition). CCB Project Design Document – July 4, 2011 Executive Summary Colombia is home to over 10% of the world’s plant and animal species despite covering just 0.7% of the planet’s surface, and has more registered species of birds and amphibians than any other country in the world. Along Colombia’s northwest border with Panama lies the Darién region, one of the most diverse ecosystems of the American tropics, a recognized biodiversity hotspot, and home to two UNESCO Natural World Heritage sites. The spectacular rainforests of the Darien shelter populations of endangered species such as the jaguar, spider monkey, wild dog, and peregrine falcon, as well as numerous rare species that exist nowhere else on the planet. The Darién is also home to a diverse group of Afro-Colombian, indigenous, and mestizo communities who depend on these natural resources. On August 1, 2005, the Council of Afro-Colombian Communities of the Tolo River Basin (COCOMASUR) was awarded collective land title to over 13,465 hectares of rainforest in the Serranía del Darién in the municipality of Acandí, Chocó in recognition of their traditional lifestyles and longstanding presence in the region. If they are to preserve the forests and their traditional way of life, these communities must overcome considerable challenges. During 2001- 2010 alone, over 10% of the natural forest cover of the surrounding region was converted to pasture for cattle ranching or cleared to support unsustainable agricultural practices. -

Volume 41, 2000

BAT RESEARCH NEWS Volume 41 : No. 1 Spring 2000 I I BAT RESEARCH NEWS Volume 41: Numbers 1–4 2000 Original Issues Compiled by Dr. G. Roy Horst, Publisher and Managing Editor of Bat Research News, 2000. Copyright 2011 Bat Research News. All rights reserved. This material is protected by copyright and may not be reproduced, transmitted, posted on a Web site or a listserve, or disseminated in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the Publisher, Dr. Margaret A. Griffiths. The material is for individual use only. Bat Research News is ISSN # 0005-6227. BAT RESEARCH NEWS Volume41 Spring 2000 Numberl Contents Resolution on Rabies Exposure Merlin Tuttle and Thomas Griffiths o o o o eo o o o • o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 o o o o o o o o o o o 0 o o o 1 E - Mail Directory - 2000 Compiled by Roy Horst •••• 0 ...................... 0 ••••••••••••••••••••••• 2 ,t:.'. Recent Literature Compiled by :Margaret Griffiths . : ....••... •"r''• ..., .... >.•••••• , ••••• • ••< ...... 19 ,.!,..j,..,' ""o: ,II ,' f 'lf.,·,,- .,'b'l: ,~··.,., lfl!t • 0'( Titles Presented at the 7th Bat Researc:b Confei'ebee~;Moscow :i'\prill4-16~ '1999,., ..,, ~ .• , ' ' • I"',.., .. ' ""!' ,. Compiled by Roy Horst .. : .......... ~ ... ~· ....... : :· ,"'·~ .• ~:• .... ; •. ,·~ •.•, .. , ........ 22 ·.t.'t, J .,•• ~~ Letters to the Editor 26 I ••• 0 ••••• 0 •••••••••••• 0 ••••••• 0. 0. 0 0 ••••••• 0 •• 0. 0 •••••••• 0 ••••••••• 30 News . " Future Meetings, Conferences and Symposium ..................... ~ ..,•'.: .. ,. ·..; .... 31 Front Cover The illustration of Rhinolophus ferrumequinum on the front cover of this issue is by Philippe Penicaud . from his very handsome series of drawings representing the bats of France. -

Mammalia: Chiroptera) En Colombia

ISSN 0065-1737 Acta Zoológica MexicanaActa Zool. (n.s.), Mex. 28(2): (n.s.) 341-352 28(2) (2012) DISTRIBUCIÓN, MORFOLOGÍA Y REPRODUCCIÓN DEL MURCIÉLAGO RAYADO DE OREJAS AMARILLAS VAMPYRISCUS NYMPHAEA (MAMMALIA: CHIROPTERA) EN COLOMBIA MIGUEL E. RODRÍGUEZ-POSADA1 & HÉCTOR E. RAMÍREZ-CHAVES2 1 Grupo de investigación en conservación y manejo de vida silvestre, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Dirección correspondencia: Calle 162 # 54-09 torre 1, apartamento 404, Senderos del Carmel 2. Bogotá D. C., Colombia. <[email protected]> 2 Erasmus Mundus Master Programme in Evolutionary Biology: Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich, Germany y University of Groningen, The Netherlands. < [email protected]> Rodríguez-Posada, M. E. & H. E. Ramírez-Chaves. 2012. Distribución, morfología y reproducción del murciélago rayado de orejas amarillas Vampyriscus nymphaea (Mammalia: Chiroptera) en Colombia. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (n. s.), 28(2): 341-352. RESUMEN. Presentamos información sobre la distribución geográfica, morfología y reproducción de Vampyriscus nymphaea en Colombia, basándonos en la revisión de especímenes museológicos de co- lecciones colombianas. Previamente la distribución de V. nymphaea en Colombia se consideraba res- tringida a las tierras bajas al occidente de la cordillera Occidental en la región Pacífico; en este trabajo confirmamos la presencia de esta especie en la región Caribe y en el nororiente de la cordillera Occiden- tal de los Andes colombianos en el Bajo Río Cauca. La morfología externa y craneana de la especie fue homogénea y el análisis de dimorfismo sexual secundario de las poblaciones de la región Pacífico no mostró diferencias significativas, sin embargo la longitud de la tibia y la profundidad de la caja craneana son proporcionalmente mayores en los machos y el ancho zigomático en las hembras. -

Karubats Niouz, Nous Traitons D’Un Sujet D’Actualité En Guade- Les Chauves-Souris Loupe : Le Développement De L’Énergie Éolienne

K arubats Niouz La lettre d’information du Groupe Chiroptères de Guadeloupe N°2 - 2015 Eolien et Chiroptères p.2 Edito Dans ce nouveau numéro de Karubats Niouz, nous traitons d’un sujet d’actualité en Guade- Les chauves-souris loupe : le développement de l’énergie éolienne. en entreprise Nous éclairons le lecteur sur l’impact que peut p.12 avoir cette activité sur certaines espèces de chauves-souris quand leur présence n’est pas suFFisamment prise en compte. Suivi d’une colonie La rubrique "des chauves-souris et des De Fers-de-lances communs hommes » met en exergue un bel exemple de p.23 donnant-donnant entre les Fers-de-lances com- muns et une entreprise locale, Phytobôkaz ! Et notre reporter Manzel Ardops de Fond dupré des Grands-Fonds interroge son Fondateur, le Dr Henri Joseph. Sommaire L’espèce poto mitan de notre biodiversité est le Sturnire de Guadeloupe. Vous découvrirez en 2 Eolien et chiroptères quoi elle participe à la luxuriance de la Forêt tro- 11 Des Chauves-Souris et des Hommes picale humide. Mise en ligne des fiches ‘Molosses‘. L’aide précieuse des chauves-souris au sein de l’entreprise Le zoom espèce est consacré à une espèce Phytobocaz rare, le Chiroderme de la Guadeloupe. 14 Les Chauves-Souris Poto Mitan de notre biodiversité Vous trouverez les synthèses de nos principales . Sturnire de Guadeloupe et ailes à mouches études menées en 2014 et 2015, de l’étude 16 Zoom Espèce : Le Chiroderme de Guadeloupe d’envergure réalisée pour l’évaluation des 18 Etudes et suivis chauves-souris dans les bananeraies aux suivis . -

Lista Patron Mamiferos

NOMBRE EN ESPANOL NOMBRE CIENTIFICO NOMBRE EN INGLES ZARIGÜEYAS DIDELPHIDAE OPOSSUMS Zarigüeya Neotropical Didelphis marsupialis Common Opossum Zarigüeya Norteamericana Didelphis virginiana Virginia Opossum Zarigüeya Ocelada Philander opossum Gray Four-eyed Opossum Zarigüeya Acuática Chironectes minimus Water Opossum Zarigüeya Café Metachirus nudicaudatus Brown Four-eyed Opossum Zarigüeya Mexicana Marmosa mexicana Mexican Mouse Opossum Zarigüeya de la Mosquitia Micoureus alstoni Alston´s Mouse Opossum Zarigüeya Lanuda Caluromys derbianus Central American Woolly Opossum OSOS HORMIGUEROS MYRMECOPHAGIDAE ANTEATERS Hormiguero Gigante Myrmecophaga tridactyla Giant Anteater Tamandua Norteño Tamandua mexicana Northern Tamandua Hormiguero Sedoso Cyclopes didactylus Silky Anteater PEREZOSOS BRADYPODIDAE SLOTHS Perezoso Bigarfiado Choloepus hoffmanni Hoffmann’s Two-toed Sloth Perezoso Trigarfiado Bradypus variegatus Brown-throated Three-toed Sloth ARMADILLOS DASYPODIDAE ARMADILLOS Armadillo Centroamericano Cabassous centralis Northern Naked-tailed Armadillo Armadillo Común Dasypus novemcinctus Nine-banded Armadillo MUSARAÑAS SORICIDAE SHREWS Musaraña Americana Común Cryptotis parva Least Shrew MURCIELAGOS SAQUEROS EMBALLONURIDAE SAC-WINGED BATS Murciélago Narigudo Rhynchonycteris naso Proboscis Bat Bilistado Café Saccopteryx bilineata Greater White-lined Bat Bilistado Negruzco Saccopteryx leptura Lesser White-lined Bat Saquero Pelialborotado Centronycteris centralis Shaggy Bat Cariperro Mayor Peropteryx kappleri Greater Doglike Bat Cariperro Menor -

Predictors of Bat Species Richness Within the Islands of the Caribbean Basin

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum Museum, University of Nebraska State 10-11-2019 Predictors of Bat Species Richness within the Islands of the Caribbean Basin Justin D. Hoffman McNeese State University, [email protected] Gabrielle Kadlubar McNeese State University, [email protected] Scott C. Pedersen South Dakota State University, [email protected] Roxanne J. Larsen University of Minnesota, [email protected] Peter A. Larsen University of Minnesota, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museummammalogy Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Hoffman, Justin D.; Kadlubar, Gabrielle; Pedersen, Scott C.; Larsen, Roxanne J.; Larsen, Peter A.; Phillips, Carleton J.; Kwiecinski, Gary G.; and Genoways, Hugh H., "Predictors of Bat Species Richness within the Islands of the Caribbean Basin" (2019). Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum. 293. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museummammalogy/293 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum, University of Nebraska State at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Justin D. Hoffman, Gabrielle Kadlubar, Scott C. Pedersen, Roxanne J. Larsen, Peter A. Larsen, Carleton J. Phillips, Gary G. Kwiecinski, and Hugh H. Genoways This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ museummammalogy/293 Hoffman, Kadlubar, Pedersen, Larsen, Larsen, Phillips, Kwiecinski, and Genoways in Special Publications / Museum of Texas Tech University, no. -

<I>Artibeus Jamaicensis</I>

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum Museum, University of Nebraska State 6-1-2007 Phylogenetics and Phylogeography of the Artibeus jamaicensis Complex Based on Cytochrome-b DNA Sequences Peter A. Larsen Texas Tech University, [email protected] Steven R. Hoofer Matthew C. Bozeman Scott C. Pedersen South Dakota State University, [email protected] Hugh H. Genoways University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museummammalogy Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Molecular Genetics Commons, and the Zoology Commons Larsen, Peter A.; Hoofer, Steven R.; Bozeman, Matthew C.; Pedersen, Scott C.; Genoways, Hugh H.; Phillips, Carleton J.; Pumo, Dorothy E.; and Baker, Robert J., "Phylogenetics and Phylogeography of the Artibeus jamaicensis Complex Based on Cytochrome-b DNA Sequences" (2007). Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum. 53. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museummammalogy/53 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum, University of Nebraska State at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mammalogy Papers: University of Nebraska State Museum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Peter A. Larsen, Steven R. Hoofer, Matthew C. Bozeman, Scott C. Pedersen, Hugh H. Genoways, Carleton J. Phillips, Dorothy E. Pumo, and Robert J. Baker This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ museummammalogy/53 Journal of Mammalogy, 88(3):712–727, 2007 PHYLOGENETICS AND PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF THE ARTIBEUS JAMAICENSIS COMPLEX BASED ON CYTOCHROME-b DNA SEQUENCES PETER A. -

Amazon Alive: a Decade of Discoveries 1999-2009

Amazon Alive! A decade of discovery 1999-2009 The Amazon is the planet’s largest rainforest and river basin. It supports countless thousands of species, as well as 30 million people. © Brent Stirton / Getty Images / WWF-UK © Brent Stirton / Getty Images The Amazon is the largest rainforest on Earth. It’s famed for its unrivalled biological diversity, with wildlife that includes jaguars, river dolphins, manatees, giant otters, capybaras, harpy eagles, anacondas and piranhas. The many unique habitats in this globally significant region conceal a wealth of hidden species, which scientists continue to discover at an incredible rate. Between 1999 and 2009, at least 1,200 new species of plants and vertebrates have been discovered in the Amazon biome (see page 6 for a map showing the extent of the region that this spans). The new species include 637 plants, 257 fish, 216 amphibians, 55 reptiles, 16 birds and 39 mammals. In addition, thousands of new invertebrate species have been uncovered. Owing to the sheer number of the latter, these are not covered in detail by this report. This report has tried to be comprehensive in its listing of new plants and vertebrates described from the Amazon biome in the last decade. But for the largest groups of life on Earth, such as invertebrates, such lists do not exist – so the number of new species presented here is no doubt an underestimate. Cover image: Ranitomeya benedicta, new poison frog species © Evan Twomey amazon alive! i a decade of discovery 1999-2009 1 Ahmed Djoghlaf, Executive Secretary, Foreword Convention on Biological Diversity The vital importance of the Amazon rainforest is very basic work on the natural history of the well known. -

Systematic Revision of the Neotropical Fruit Bats of the Genus Sturnira : A

SYSTEMATIC REVISION OF THE NEOTROPICAL FRUIT BATS OF THE GENUS Sturnira: A MOLECULAR AND MORPHOLOGICAL APPROACH By CARLOS ALBERTO IUDICA A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2000 Copyright 2000 by Carlos A. ludica This work is dedicated to Maria Eugenia Fullana Jornet, the most important person in my life and to John Frederick Eisenberg, an eminent scientist whose influential company will be missed after his retirement. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project would not have been possible without the help, support, and encouragement of many people. Most significantly, I thank John F. Eisenberg for suggesting the phylogeny of the entire genus Sturnira as a dissertation subject. W. Mark Whitten and Norris H. Williams guided me through all the lab work involved in this project. I thank them also for their willingness to maintain endless conversations on varied subjects, from science to history, from politics to life. For their suggestions during the planning stage, for assisting on every aspect of my work, and for helping me to process and interpret the data, I thank the members of my committee: Brian Bowen, Colin Chapman, John F. Eisenberg (Chairperson), Walter Judd, and Norris H. Williams. Although W. Mark Whitten was not a formal member of my committee, his daily contributions were essential to the development of this work and he deserves an honorary seat on my committee. I thank Wesley E. Higgins, Juan Manuel Alvarez, Savita Shankar, Ana "Sam" Bass, and Ginger A. M. -

Volunteer Program

Volunteer Program Surveys in March 2018 Annabelle Mall (B.Sc.) Content 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Methodology ................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Mammals Survey Methodology .............................................................................. 4 2.2 Herpetology Survey Methodology .......................................................................... 4 2.3 Tropical Flora Survey Methodology ....................................................................... 5 3 Results ............................................................................................................................ 6 3.1 Results of Mammals Survey ................................................................................... 6 3.2 Results of Herpetology Survey ................................................................................ 8 3.3 Results of Tropical Flora Survey............................................................................. 9 4 Discussion and Conclusion ........................................................................................... 12 5 Literature cited .............................................................................................................. 14 Appendix .............................................................................................................................. 15 1 Introduction -

Supporting Files

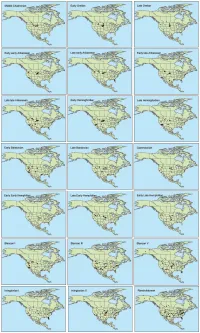

Table S1. Summary of Special Emissions Report Scenarios (SERs) to which we fit climate models for extant mammalian species. Mean Annual Temperature Standard Scenario year (˚C) Deviation Standard Error Present 4.447 15.850 0.057 B1_low 2050s 5.941 15.540 0.056 B1 2050s 6.926 15.420 0.056 A1b 2050s 7.602 15.336 0.056 A2 2050s 8.674 15.163 0.055 A1b 2080s 7.390 15.444 0.056 A2 2080s 9.196 15.198 0.055 A2_top 2080s 11.225 14.721 0.053 Table S2. List of mammalian taxa included and excluded from the species distribution models. -

BATS of the Golfo Dulce Region, Costa Rica

MURCIÉLAGOS de la región del Golfo Dulce, Puntarenas, Costa Rica BATS of the Golfo Dulce Region, Costa Rica 1 Elène Haave-Audet1,2, Gloriana Chaverri3,4, Doris Audet2, Manuel Sánchez1, Andrew Whitworth1 1Osa Conservation, 2University of Alberta, 3Universidad de Costa Rica, 4Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute Photos: Doris Audet (DA), Joxerra Aihartza (JA), Gloriana Chaverri (GC), Sébastien Puechmaille (SP), Manuel Sánchez (MS). Map: Hellen Solís, Universidad de Costa Rica © Elène Haave-Audet [[email protected]] and other authors. Thanks to: Osa Conservation and the Bobolink Foundation. [fieldguides.fieldmuseum.org] [1209] version 1 11/2019 The Golfo Dulce region is comprised of old and secondary growth seasonally wet tropical forest. This guide includes representative species from all families encountered in the lowlands (< 400 masl), where ca. 75 species possibly occur. Species checklist for the region was compiled based on bat captures by the authors and from: Lista y distribución de murciélagos de Costa Rica. Rodríguez & Wilson (1999); The mammals of Central America and Southeast Mexico. Reid (2012). Taxonomy according to Simmons (2005). La región del Golfo Dulce está compuesta de bosque estacionalmente húmedo primario y secundario. Esta guía incluye especies representativas de las familias presentes en las tierras bajas de la región (< de 400 m.s.n.m), donde se puede encontrar c. 75 especies. La lista de especies fue preparada con base en capturas de los autores y desde: Lista y distribución de murciélagos de Costa Rica. Rodríguez